Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

10 Stories Far Ahead of Their Time

Audiences like when a work of fiction is on the bleeding edge of a new cultural era. Put the premise, genre devices, and storytelling techniques far enough ahead of their time, however, and the result can be uncanny, if not downright bewildering. After all, without other authors to influence their work, these storytellers are, in a practical sense, working in the dark.

This could lead to weird ways that their stories subvert the popular tropes of their genres because those tropes hadn’t been codified yet. Even if an author imagines a futuristic piece of technology or societal standards broadly correctly, a reader would instinctively focus more on what the author got wrong than right. Yet the authors of these stories still deserve appreciation for their acts of imagination.

Related: Ten Eerily Prescient Past Predictions About Life in the Future

10 “The Machine Stops”

E.M. Forster’s short story is a small paradox: It’s a tale that is both visionary and reactionary. It tells of people who live underground in isolated rooms, communicating with each other remotely through microphones and moving images. They barely even leave their chambers and thus have become pale, flabby things, looked after by a sort of benevolent mechanical system simply called The Machine. But a rebel named Kuno (fans of the hit 2019 game Disco Elysium perk up) has heard about humans living on the surface and wishes to throw off the constraints of living in the heart of the machine. He makes a good call since the title spoils what happens at the end.

Forester wrote this in response to H.G. Wells’s scientific socialist parable A Modern Utopia. It’s an interesting clash of influences and perspectives. Wells’s Eloi from his 1895 book The Time Machine has many parallels to what becomes of humanity in the heart of the Machine, but the Eloi’s pitiful state is a result of capitalist class societies.

What’s startling about the story isn’t that it prefigures issues like parasocial internet relationships or overreliance on services like Zoom. Being written in 1909, it prefigures synchronized sound for moving images! In fact, consumer-grade radio was still more than a decade off when Forester gave us this remarkably prescient vision of the future, though hopefully, we can change some of our habits before it becomes too accurate.[1]

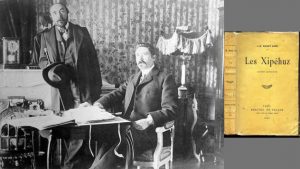

9 The Shapes

Speaking of Wells, his 1898 novel War of the Worlds is generally regarded as the first book to pit human beings against aliens. In fact, he was beaten to the punch by about ten years. However, for many, a barrier to learning about the earlier story is that it was only available in French until Jason Colavito released an English translation. Les Xipéhuz—to use its untranslated title—was written by the writing team J.H. Rosny-Aine in 1888 and was their first science fiction-like story.

The Shapes is about a Mesopotamian tribe circa 5000 BC who discovers an extremely dangerous race of blue cone, cylinder, and disc-shaped aliens simply called The Shapes, capable of setting humans on fire at a range. There are a number of disastrous encounters. The humans attempt to sacrifice a horse in honor of The Shapes, which the aliens seem to interpret as a threat. In desperation, the tribesmen turn to a more science-minded misfit named Bokhunen, who is able to find a weakness in The Shapes through the application of the scientific method.

Predating the popularity of science fiction as a genre, it went in some surprising directions, especially for its time. For one thing, it’s never established that The Shapes came from another planet. They could have been a bizarre but Earth-based evolutionary offshoot. Further, the authors describe death cults that arise in response to the Shapes’ attacks, cultists believing those deaths are a judgment from the gods.

Most surprising of all, there are scenes where Bokhunen observes how The Shapes essentially reproduce by releasing clouds of spores. As Chris Lackey said on the H. . Lovecraft Literary Podcast episode on the story, such scenes are more expected of 1970s psychedelic fiction than 19th-century historical fiction.[2]

8 Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song-Book

While this 1744 book is itself fairly obscure, it’s the earliest surviving printing of many nursery rhymes that will be familiar from elementary school. It’s the earliest known copy of “Mary Mary, Quite Contrary,” “Baa Baa Black Sheep,” and “Hickory Dickory Dock.” All the favorites.

What’s most striking about the book is how unsuitable for the very young many of the stories would be considered today. One is literally “Piss a Bed.” And there’s “My Mill,” which asserts that while the speaker’s mill grinds pepper and spice, the person they’re addressing has a mill that grinds “rats and mice.”

Perhaps the most offensive passage is when “Piss a Bed” insists that “butt” rhymes with “up.” So, while it’s fashionable to attribute the edginess that kids’ entertainment had for a while to the Brothers Grimm in the 19th century, this book shows that such grimness was there to be found in children’s literature most of a century earlier.[3]

7 The Notting Hill Mystery

For fans of the mystery genre, it’s fairly common knowledge that the first detective mystery novel is The Moonstone: A Romance in 1868 by Wilkie Collins. As will surely not be a surprise to you by now, Collins was actually beaten to the punch by six years. The writer who pulled that off was Charles Warren Adams, writing as Charles Felix. His tale was the 1862 magazine serial that was republished as a book in 1865, The Notting Hill Mystery. The novel is styled as a series of letters for a murder investigation.

Yet, with no paradigm for a murder mystery novel to follow, Adams made some choices that today read as quite dubious. First off, the setup for the murders—that the victim happened to drink poison while sleepwalking and that it came to light her husband had taken out three insurance policies on her—is a bit contrived and silly (the researcher who brought the book back to public attention on National Public Radio couldn’t resist making little jokes).

Second, the detective isn’t a private investigator or anything so emotionally engaging but an insurance investigator, removing him from the action that is likely to lower the reader’s interest. Most of all, the investigator doesn’t bring the perpetrator to justice, which takes away much of the emotional catharsis. Nonetheless, it was reported that the novel caused quite a stir in its day. However, stories with more crowd-pleasing plot elements are the most likely culprit for why the book didn’t linger in the literary scene.[4]

6 Romance in Marseille

Claude McKay was hardly unknown in his lifetime. He was one of the pillars of the Harlem Renaissance and, in 1928, became the first black American author to reach the bestsellers list. Yet even he had to admit that this novel, effectively completed in 1933, was unpublishable at the time. So he set it aside when he was done with it.

When it was published in 2020, the subject matter and content were so fashionable that it practically sounded like what a conservative comedian would joke was the plot of the book of the month among liberals: A Morrocan who stowed away on a trip to New York City wins a lawsuit because his feet were amputated as a result of frostbite incurred while he was imprisoned on his journey. He returns to Marseille and mingles with prostitutes, working-class queer characters, socialists, and so on.

As Molly Young pointed out in Vulture Magazine: about the only note of dissonant values McKay put in it was a stereotypical Jewish lawyer. Even the most forward-looking stories bring some cultural baggage of their times with them.[5]

5 Journey to the West

Imagine if Homer’s Odyssey was Chinese, Odysseus was a monk with a crew of colorful monsters on a mission to deliver teachings to a heathen region over a few years, and the whole thing is an intentional comedy. That gives you some sense of the flavor of this Ming Dynasty-era novel from 1592. It is attributed to Wu Cheng’en, who didn’t put his name on it in his lifetime because it was written in a style regarded as vulgar for the time. Considering that the novel features such passages as a scene where the monkey king Sun Wukong urinates in the hand of the Buddha, it makes sense that a 16th-century author would worry about his book upsetting the wrong people.

How many modern tropes appear in this fantasy epic? For starters, before the first page is done, the breakout character/cultural icon Sun Wukong, having been born from a big rock, accidentally acquires powers to fire lasers from his eyes by bowing to the four directions of the compass and frightens Heaven’s Jade Emperor. It features the story of the real, celebrated missionary Xuanzang (renamed Tripitaka), who brought Buddhist teachings to India and includes a huge array of other mythological beings, prefiguring modern crossover fiction such as The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

There is lots of playful deconstruction of fantasy tropes, such as Sun Wukong becoming immortal six times over and threatening to overthrow Heaven. It is surprising that despite being too vulgar for polite society of the time, it has become widely influential, such as the iconic anime Dragonball Z, featuring a cast where many of the main characters are knockoffs.[6]

4 “The Great Automatic Grammizator”

Before 2023, this 1953 story was hardly among Roald Dahl’s most celebrated. It’s a yarn about inventor and aspiring writer John Knipe creating a machine that is programmed to arrange words by certain grammatical patterns and eventually has plot structures programmed into it. Gradually, it creates enough passable stories that the mediocre writers of the world have to agree to have their styles absorbed into its programming or driven out of business.

Dahl could not claim to have wholly invented this notion. George Orwell’s 1984 from 1949 features the Ingsoc government using a “versificator” for creating government-sanctioned music without human input and another program for creating smut. Yet Dahl’s emphasis on the effect this has on the publishing industry and the working creatives is what really made it resonate seventy years later.[7]

3 “The Three Apples”

The Notting Hill Mystery from 1862 was the first detective mystery novel, but the first detective mystery short story was generally believed to be Edgar Allan Poe’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue” from 1841. This turned out to be off by about 900 years. Centuries before Poe’s home continent was even discovered by Europe, the short story collection that came to be known as 1001 Arabian Nights offered up the story of Jafar the vizier being forced to investigate the case of the woman who was found hacked up in a trunk at the bottom of a river. To increase the stakes, Jafar is given a three-day deadline before he himself would be executed if he didn’t find the culprit.

There are a few ways that the story is not one of Scheherazade’s best. For one thing, Jafar is an unusually passive protagonist, only lucking out that characters are confessing to the crimes he is supposed to investigate independent of his actions or that someone with key evidence happens to live in his house. For another, Jafar devotes more energy to whining about his fate than investigating. Still, with how different society was millennia ago, the world’s first murder mystery can be expected to have a few stylistic differences that rub a modern reader the wrong way.[8]

2 “The Green Knight”

Claude McKay was probably correct that he would have had a commercial flop on his hands and perhaps would have gotten in some legal trouble if he’d published Romance in Marseille when he wrote it. However, he probably wouldn’t have been putting his life on the line. But what about the anonymous author of “The Green Knight”? Consider that when the famous poem of King Arthur’s knight Sir Gawain is generally to have been written about AD 1390, it was less than a century after the various states in Europe had declared homosexuality a crime punishable by being burned at the stake.

The poem, as anyone who has seen the 1973 or 2021 film adaptations knows, details Sir Gaiwan going to meet the green knight to have his head chopped off in trade for having cut the green knight’s head off at Christmas in Camelot the year before. On the way, he stops by the castle of Lord Bertilak, where an arrangement is made that Gaiwan will receive a trophy from the lord’s hunts in exchange for Gaiwan giving back everything he receives at the castle. Because Lady Bertilak kisses Gaiwan repeatedly, Gaiwan passes the kisses on to the lord before resuming his quest.

Even with the massive shift in LGBT cultural norms, the 2021 film is actually much less comfortable with homosexual interaction than the poem. As Princess Weekes pointed out in a review for TheMarySue.com, the power dynamic is made unequal (Lord Bertilak has obvious power and forces the kiss on a much younger Gawain). It goes to show that societal standards will not always be black and white, especially when green is involved.[9]

1 True History

Finally, a tale from 2nd-century AD Greece that is widely credited with being the first science fiction piece ever written, and it’s a parody of the travelog genre. Lucian, a Syrian satirist best remembered for the work he did in Athens, wrote sarcastic guides for how to live life, such as “Teachers of Orators,” where he recommends being a successful orator by essentially lying a lot. Think Macchiaveli’s The Prince but written millennia earlier. Lucian begins his novella-length True History with the preface, “I confidently pronounce for a truth, I lie.”

Lucien goes on to describe a fifty-man voyage of inspired absurdity he went on where, eventually, he and his crew sailed into space on a wooden ship carried by a whirlwind. They arrive on the Moon just in time to discover the vulture-riding moon people are about to go to fight a great battle with the ant-riding people from the Sun for control of Venus. The moon people’s army has infantry and non-flying cavalry to fight in the battle.

Lucian describes how to create a two-dimensional battlefield for them to fight on: Giant spiders are dispatched to make an enormous web between the Moon and Venus for the soldiers and mounts. It’s such a bizarre notion that it would be very hard to imagine it even occurring to a modern sci-fi writer since now we’ve all grown up with spaceships and other such notions. It goes to show the sheer imagination that Lucian put into his sarcasm.[10]

Dustin Koski is the author of Robin Hood vs. King Arthur, a story that is also both ahead of and behind its time.