Technology

Technology  Technology

Technology  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

10 Fascinating Facts About Life in Hawaii Before the U.S. Arrived

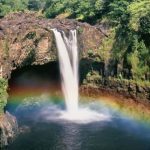

Hawaii joined the Union on August 21, 1959. Its history immediately before and after joining the United States is well known. Americans have long learned about the attack on Honolulu’s Pearl Harbor in 1941. Many recognize Hawaii’s role as a Pacific hub for logistics, trade, and transportation. The islands offer economic opportunities in commercial fishing and many other industries. And, of course, warm weather and beautiful beaches make Hawaii a must-see tourist trip.

But long before Hawaii became a state, islanders thrived. Today’s 50th state has a history that stretches back centuries. Early 20th-century colonialism changed Hawaii. And 1959’s statehood gave the tropical paradise a new set of circumstances. But the islands’ pre-statehood history remains fascinating. Here are ten true tidbits about what life was like in the Hawaii of old.

Related: 10 Facts About Life in the World’s Tiniest Island Nation

10 Brave Marquesan and Powerful Tahitian Immigrants

Just a few hundred years after Jesus’ birth and half a world away, Hawaii was settled. Travelers from the Marquesas Islands sailed more than 2,000 miles (3,218 km) to Hawaii’s Big Island as early as AD 400. For generations, Marquesans lived in Hawaii as skilled farmers and expert fishermen. From time to time, chieftains battled for territory, but the population was steady. Then, after a few centuries, more Polynesians arrived.

Around AD 1000, Tahitian sailors in double-hulled canoes struck out for Hawaii. After a 2,400-mile (3,862-km) journey across the massive Pacific Ocean, they reached land. That they found Hawaii at all is incredible. The Tahitians traveled in dugout wooden longboats with little food and no navigational tools. Their journey to Hawaii remains one of the most incredible adventure stories of all time.

Once on land, the powerful newcomers subdued the locals. This new wave of sailors brought with them a Tahitian style of government. That system was sophisticated for its time, and it overwhelmed the Marquesan descendants. The Tahitian settlers quickly divided the islanders into rigid social classes. Political leadership was given to elite Tahitian leaders, or “ali’i,” while “mokupuni” commoners did as ordered.

Tahitians took charge of farmlands and fishing stocks. For the next three centuries, more waves of Tahitian sailors landed in Hawaii and solidified their rule. But by 1300, wind patterns in the Pacific changed. With less favorable winds at their departure point, Tahitians stopped sailing north. For the next few centuries, those who’d already settled the land lived quietly among themselves.[1]

9 Earliest Explorers Become “Little” Legends

Today, local legends tell of “menehune” living on the islands. According to legend, these menehune were a race of little people who secretly settled Hawaii long before the arrival of the Marquesans. Myths claim that the first Polynesian sailors noticed evidence of human settlements when they arrived around AD 400. Some modern tales allege that the Marquesans even saw temples, roads, and dams already built on the islands.

These confused sailors assumed another group must have beaten them to Hawaii. But as they settled in, they never found anyone else there. Thus, rumors began to swirl that these “first” settlers were actually little people who lived up in the mountains far out of reach. Over generations, these myths were handed down through tall tales of a secret race of little people.

In reality, this legend is half-based in fact. Today, scholars believe the menehune name actually comes from the second wave of Hawaiian settlers. When those Tahitians showed up, they cared little for their Marquesan predecessors. Since the Tahitians were used to a stratified society, it made sense for them to recreate it in Hawaii. And when they did, they naturally made Marquesans the lowest-status group of them all.

The Tahitian sailors even had a word for them: “manahune.” That insulting nickname meant “the lowly people” or “people of low status.” Tahitians treated them with contempt, too. Subjugated for centuries, Marquesans were slowly pushed out of Hawaii’s fertile lowland valleys. Eventually, they migrated deep into more mountainous regions of the Big Island to avoid brutal Tahitian rule. By the early 19th century, small bands of Marquesan descendants still lived in seclusion high up in the mountains.

As time wore on, “manahune” morphed into “menehune.” With it, an ugly reality about social classes evolved into a tall tale of mysterious little people. While the menehune don’t actually exist, the Marquesan impact on the islands can still be felt today.[2]

8 Strict Social Structures Develop

If you haven’t deduced it already, social class was a very important part of early Hawaiian society. For Tahitian settlers, a person’s birthplace and family class were used to define their entire life. Early Tahitian settlers fell into the aforementioned “ali’i” class, which comprised elite political leaders. The king, known as the “mo’i,” was the top dog. His role was to collect taxes, lead religious festivals, and prepare armies for battle.

Other ali’i members were said to have descended from the gods. For generations, their offspring continued to reap the rewards of these customs. Below them, a “kahuna” class of priests and craftsmen provided value with their religious and artisanal contributions. That class included everyone from mystical medicine men to skilled canoe builders.

The majority of society was comprised of common laborers. Tahitian settlers knew them as “maka’ainana.” They fished, farmed, served in the army, and paid taxes. Taxes were high in order to keep the ali’i in good standing: some laborers relinquished as much as two-thirds of their pay to the mo’i and his charges.

The “manahune” weren’t the only outcasts left to flounder at the very bottom of the ladder. Also low in status were the “kauwa.” These people were typically prisoners of war. After being taken by the mo’i and his army, kauwa captors were often executed or used in human sacrifice rituals. The luckiest ones could expect a lifetime of forced labor on farms.[3]

7 Keeping Close to Kapu’s Covenants

Over the next several centuries, Tahitians settled in. Descendants became Hawaiians, and the isolated islands developed a unique culture. One of the primary aspects of this lifestyle was their strict adherence to religious beliefs. The code, called “kapu,” outlined what kind of public behavior was allowed and what was forbidden. It covered nearly everything. Hawaiians’ class consciousness remained front and center. The ali’i leaders used kapu codes to keep less fortunate Hawaiians stuck in their birth caste for life.

The gods, called “akua,” and the spirits of ancestors, known as “aumakua,” supposedly dictated how kapu codes were to be followed. The rules included important rules for how commoners were supposed to interact with the king. The code also dictated lesser daily decisions. Those guidelines included rules on what foods men and women were allowed to eat, where they could eat, and what color feathers and flowers people of different classes were allowed to wear in their hair. Those who violated kapu rules risked severe punishment, even up to execution.

As white men sailed across the Pacific and reached Hawaii, the importance of kapu mores declined. Western explorers brought their own cultural values with them, including Christianity. Just as the Tahitians had done centuries earlier to the pioneering Marquesan settlers, so too did Westerners alter Hawaiian customs. Besides, lower-class Hawaiians couldn’t help but notice how early Western visitors violated kapu rules repeatedly and never seemed to be punished.

The whole thing ended in a flourish in the early 19th century. King Kamehameha the Great was ruling the islands at the time. White men frequently visited from faraway lands. Kamehameha understood what was coming, and he wanted to prepare his community. In 1819, he dined in public with a woman. Under kapu, that was an extremely forbidden act. But seeing the king himself break the taboo opened the floodgates. Soon after, kapu was completely discarded, and more modern customs took hold.[4]

6 James Cook Arrives and Fate Intervenes

James Cook’s name is forever synonymous with Hawaii. But he didn’t intend for it to be like that. And his gruesome end there surely wasn’t planned. Still, Captain Cook’s cautionary tale lives on today as an example of a voyage gone horribly wrong. Just like the Tahitians did centuries before him, Captain Cook happened upon Hawaii by accident. In early 1778, his ship sailed into Waimea Bay on the island of Kauai.

That year, Hawaiians were in the middle of a historic period of peace and good fortune called “makahiki.” Inter-island warfare was non-existent, and political tensions were low. In other words, Cook showed up at the perfect time. Hawaiians showed incredible generosity to their unexpected white visitors. Ironically, Cook and his men had just sailed up from Tahiti. Thus, they knew a little bit about the general customs of the South Pacific, even if the Hawaiians were a mystery. Still, locals gave gifts to Cook’s men. The British sailors returned the favor with their own trinkets. Island women even welcomed Cook’s crew warmly in more adult-oriented ways.

Later that year, Cook sailed back through on another voyage. This time, he landed on the Big Island. Again, he showed up during makahiki. The islanders once again welcomed him with open arms. Cook sailed off soon, no doubt impressed by Hawaiian hospitality. But when he returned a third time, in February 1779, he wouldn’t be so lucky. Cook had been planning on sailing north that month. But bad weather forced him to return to Hawaii. He was hoping to wait out ocean squalls for a few weeks.

Unfortunately for him, makahiki was over. Tensions on the islands were high. That energy spilled into Cook’s return. When the captain’s crew saw a Hawaiian man with a pair of metal tongs, they accused him of theft. More accusations flew over the next few days. On Valentine’s Day, 1779, Cook attempted to hold a conference on the beach with Hawaiian leaders.

During the meeting, a shot was fired from a British ship floating in the bay. It struck a Hawaiian chief. Enraged locals mobbed Cook’s men in defense of their beloved leader. Captain Cook and many of his men were killed in the ensuing skirmish. Cook’s crew sought revenge days later. They killed several dozen Hawaiians before sailing away for good.[5]

5 Hawaiians Flourish Through the Sandalwood Trade

Violence aside, Captain Cook’s voyage was a sign of things to come. By the late 18th century, the sandalwood trade reached Hawaii. The islands boasted a large stock of sandalwood forests. The trees were plentiful down by the beaches and far up into the mountains. The tree’s wood is dense and sturdy and thus highly valued for carving furniture. Plus, its bark can be ground into oil. The sweet fragrance produced is used in cosmetics, soaps, and perfumes.

Western traders had already been doing a brisk sandalwood business deeper in the South Pacific. But sandalwood stocks were running low in places like the New Hebrides, the Solomon Islands, and New Guinea. So when white men descended upon Hawaii, the exchange was ready-made. Hawaiians quickly figured out the sandalwood business. They loaded up ships bound for China with tree trunks by the hundreds. In turn, merchant mariners came back with highly-valued silk and porcelain. For a long time, the sandalwood trade brought prosperity to Hawaii.

Hawaii also had one other thing traders desperately wanted: salt. Fur traders and whalers made Hawaii a key destination to load up on salt. Merchants would pack animal hides in it to cure them. Whalers needed the salt to preserve deep-sea catches for the long journey home. As with sandalwood, Hawaiians ran a brisk business. Westerners came through in all directions. For a long time, things worked out for all parties. But after decades of plenty, the islands’ sandalwood forests began to dwindle.

Overworked natives were being forced to trek further up mountain volcanoes to chop trees. Many were severely hurt doing the physically demanding job. The injuries became so common, and the business’s margins became so brutal that Hawaiian parents started pulling up sandalwood roots. They hoped their kids wouldn’t have to work themselves to the bone for the visiting merchants. Eventually, the sandalwood trade collapsed. Today, Hawaiian ranchers raise cattle in open fields where thick sandalwood forests once flourished.[6]

4 Whalers Swoop In and Overwhelm the Place

The sandalwood trade sputtered to a halt in the mid-1800s. However, commercial fishermen and fur traders continued to seek out Hawaiian shores throughout the 19th century. Whaling ships came to the islands from every direction. Most notably, whalers from New England sailed all the way around the Americas and out to Hawaii.

The long voyages were worth it: The warm Pacific waters were full of whales and other sought-after marine species. In homes across New England, millions demanded heating oil for lamps and lights. Whale blubber was the best substance to get the job done. So, American whalers made the long trek to work Hawaii’s shores. When they got to the islands, the sailors were relentless.

Aside from blubber for oil, traders also sought whale bones to make everything from corsets to umbrellas and buggy whips. Fortune followed. Vice did, too. Oahu and Lahaina were particularly popular destinations for visiting whalers. In those towns, gambling dens and prostitution houses went up by the dozen. Whalers’ bad behavior became the stuff of legend. For decades, their devilish ways clashed with the pious attitudes of Christian missionaries who were also busy in Hawaii.

Each group changed Hawaiian culture in their own indelible ways. For the whalers, it all finally ended in the late 19th century. Right around the time of the Civil War, oil was discovered in Pennsylvania. An oil rush soon descended on the state. Overnight, oil became one of the most valuable commodities in America. Among other things, it put an end to some of the most aggressive whaling tactics used in the Pacific. Slowly at first, and then all at once, whalers sailed out of Hawaii and returned home to ply a new trade. Islanders were finally free of the misbehaving mariners. However, the missionaries remained.[7]

3 One Powerful King Brings the Islands Together

For centuries before Western influence, Hawaii’s islands were ruled by numerous kings and chiefs. As Captain Cook unfortunately found out, not all times were peaceful. In fact, most eras weren’t. Inter-island war was common. Skirmishes set off constantly. For generations, the islands never managed to unite. However, that changed late in the 18th century when Kamehameha emerged.

Born in the 1750s, Kamehameha was the son of a Kona chief on the Big Island. His cousin Kiawala’o was supposed to be the heir to the island’s throne. The plan was for Kamehameha to live an elite life as a high-level subordinate. But by the 1780s, Kamehameha had other plans. Trained by his family to fight, he turned his aggression on Kiawala’o. Years of brutal civil war blanketed the Big Island. Kamehameha wisely armed himself for the fight with Western-made steel guns. By 1790, he was victorious.

Awed by his shrewd rise, residents of the Big Island fell in behind Kamehameha. Soon enough, news of his exploits reached Kauai, Lanai, Oahu, Molokai, and the other islands. Kamehameha’s impressive personality and sheer force of will won the people over. In a few years, he unified all the islands under his rule. Immortality awaited: his loyal pledges anointed him King Kamehameha the Great.

For nearly three full decades, he successfully ruled over the Kingdom of Hawaii. In addition to uniting the islands, he shrewdly navigated the arrival of white men and their merchant ships. During his life, Hawaii prospered economically thanks to several high-profile trading relationships. And although his rise to power was violent, Kamehameha’s reign ended up being mostly peaceful. He died in 1819 and was given a secret burial, a customary practice of the time. Five generations of Kamehameha’s descendants followed him in line. They ruled over the kingdom until the late 19th century.[8]

2 Along Comes a New Social System: Christianity

Hawaii’s highly stratified caste system was in decline by the 19th century. Following Kamehameha’s death in 1819, the islands faced a variety of social pressures. One, as we’ve discussed, was the whaling trade. But simultaneously, another social system reached the kingdom’s shores: Christianity. As missionaries flocked to Hawaii by 1820, they brought new social customs. Old ‘kapu’ rules had already been on the decline. The Christian newcomers took advantage of this to spread Biblical values. The Gospel fit perfectly into that kapu-sized vacuum. Hawaiians took quickly to the stories of the Good Book. Jesus Christ replaced native gods in the minds and hearts of young islanders.

Christianity didn’t just spread because of good Biblical storytelling, though. Wise missionaries convinced Hawaiians they could protect them from bawdy and aggressive whalers. To the missionaries’ credit, they were proven right. Slowly, the whaling trade died down. As it did, missionaries built their flocks. Even Kamehameha worshiped at a mission congregation later in his life.

In some ways, the missionaries’ work ultimately proved detrimental to the Kingdom of Hawaii. Christian settlers paved the way for the United States to colonize the islands. Slowly, local Hawaiian leaders were stripped of power. Statehood was still a century off, but Christianity’s presence opened the door for American intrusion. But that’s not to say the missionaries didn’t do good things, too.

For one, they brought formal education. Some of their academic endeavors are still seen on the islands today. And missionaries were the first to codify the Hawaiian language. By writing it in a Latin script, these early Christian settlers standardized the native language. Decades later, it has stabilized and even flourished at times because of this early work.[9]

1 Surfing Into Statehood

Hawaiians didn’t invent surfing, but their predecessors did. Cave paintings from the 12th century depict ancient Polynesians riding wooden boards over crashing waves on the beach. Tahitian settlers likely brought an early form of surfing to Hawaii. For centuries, islanders honed the craft. It was more than a sport. For early Hawaiians, surfing was a way to honor the goodwill of the gods.

And even though their communities were stratified, surfing transcended class. Every group took to the waves. Surfing was so popular that the very first white visitors took immediate notice. The first written reference to surfing was found in none other than James Cook’s diary. He recorded notes on the popular pastime during his first visit to Hawaii, just months before his eventual death.

More than a century after Captain Cook’s downfall, in 1890, surfing’s most important figure was born. Like every young Hawaiian, Duke Kahanamoku grew up in the ocean. He was such a good swimmer that he made the U.S. Olympic team. In 1912, he swam for America at the Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden. Duke shocked the world by winning one gold and one silver medal. But surfing—or wavesliding, as Duke and his friends called it—was his real calling.

Today, historians call Kahanamoku the father of modern surfing. He spent his life on his board. He entered and won surfing competitions all over the world in Australia, California, and elsewhere. Duke was handsome, chiseled, and likable. In addition to movie star good looks, he was an amateur historian and an exceptional ukulele player. To boot, he spent three decades as Honolulu’s elected Sheriff.

In his life, he did more to promote surfing and Hawaiian culture than anyone else. He lived to see Hawaii enter the Union in 1959. Nine years later, he died of a heart attack. But before his death, Kahanamoku was inducted into both the Swimming Hall of Fame and the Surfing Hall of Fame. He was the first person to ever receive that joint honor.[10]