History

History  History

History  Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

10 Defunct Languages or Writing Systems

When word of mouth was not enough to communicate shared knowledge in prehistoric societies, images were used. When they were not able to accurately depict the complex concepts of evolving man, words arose. In the list we discover ten languages or writing systems which lost their usefulness—or never achieved the prominence hoped of them. From languages that naturally arose, to forced attempts to improve upon nature, here are ten defunct languages or writing systems.

For hundreds of years there was no religious freedom in France—forcing many people to live in small communities. Jewish settlements, although discriminated against, were allowed to use their own language—Shuadit, which thrived. Invented in the eleventh century, Shuadit was the language for Jews in France, and it thrived at a time when speaking languages other than French was frowned upon.

Shuadit continued to fly high until the French Revolution. When the revolutionaries declared freedom of religion, Jews now had the choice of going wherever they wanted. Small communities held together for hundreds of years now suddenly dispersed. This doomed the language, and Shuadit officially died in 1977 with its last speaker.

Azari was spoken in the Caucasus area in Asia—today known as Azerbaijan—for 500 years. However, the Turkish language slowly took over until only the city of Tabriz still used it. Tabriz was the capital of the area, and the ruling Shahs defiantly spoke it despite all surrounding areas speaking the new and popular Turkish-Azeri language.

However, Tabriz soon found itself in the dominion of Persia, and the administration moved to Tehran. With the capital gone, people moved away resulting in the decline of Azari. By 1600 it was no longer dominant, and by the 1800s everyone switched to the Lingua Franca, and Azari died.

For centuries, the Frisian language was competing with German for the language of Northern Germany. Since the 1100s, one variant—Saterland Frisian—was based around the moors of Saterland. That is until 1648.

After years of solitude the Catholic Church redrew the boundaries of the church, with the Bishop of Munster suddenly getting Saterland as part of his claim. As a result the Protestant Frisians began to marry German speaking Catholics. German quickly replaced Frisian, which quickly declined to where it is today—nearly dead.

For 200 years, the island of Martha’s Vineyard—off the coast of Massachusetts—had a large deaf population due to inbreeding. Deafness quickly became a norm among residents. As a result, Martha’s Vineyard residents developed their own sign language system, which was learned as a first or second language by everyone on the island.

By the late 1800s, Martha’s Vineyard sign language was starting to appear on the mainland where it was seriously threatening to take the place of American Sign Language. However, in the early 1900s, healthy deaf people started coming to the island and incidences of inbreeding dropped dramatically. This also reduced hereditary deafness and the use of the language among residents. By the 1980s, only a handful of people still knew it.

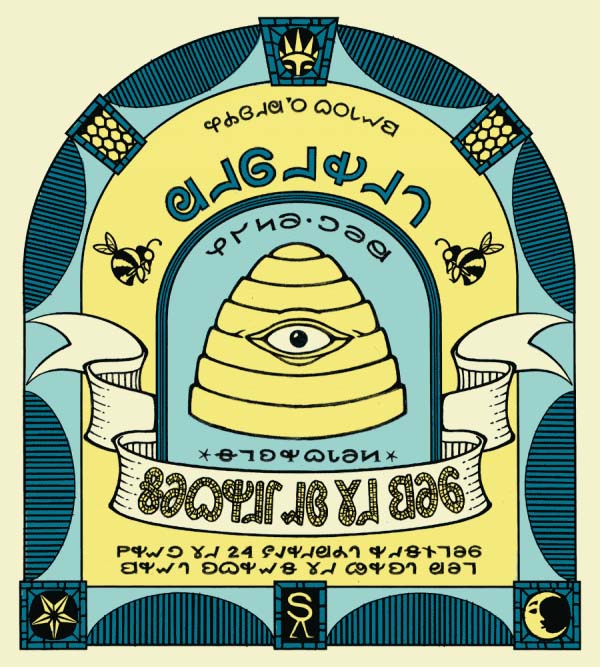

In the 1900s, famous Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw set up a new writing system to simplify spelling. Known as Shavian, the new system contained over forty new letters. The new system was well received and a worldwide contest brought it a lot of press.

Just as it was starting to catch on in the 1950s, Shaw died. When his will was executed, there was almost no money left to fund the writing system but those overseeing Shavian decided to push on and publish at least one book, thinking it would start a chain reaction. Unfortunately, everyone already had the book in English, and no one saw any reason to buy a new copy—especially one they probably couldn’t read. One book did not change the world, and Shavian soon withered, left only to a handful of enthusiasts fighting to keep it alive. Judging by how many people likely own a copy of a book in Shavian, those enthusiasts probably need to go back to enthusiasm school, or redirect their attention to something more thrilling like bird watching.

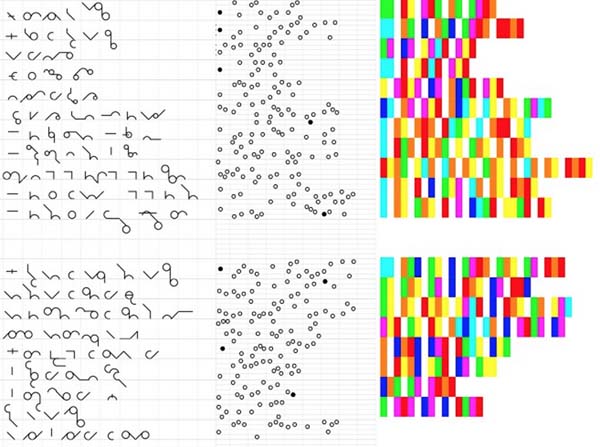

In the 1800s, the language Solresol was invented in France. Based on music, color and script, Solresol was soon known as “the musical language”. Solresol won prizes worldwide and was predicted to be the language to teach deaf children in France and quite possibly the world. The nature of the language makes is very unique, in that it could be communicated via writing, speaking, sign language, painting, singing, and even via flags.

Alas, in the late 1800s, France decided that teaching sign language to deaf children was keeping them from learning properly, and discouraged it. With no more sign language being taught, Solresol ceased to be taught. Without a big country backing it, the language was ruined. Simply because France decided that teaching deaf children was bad.

In the 1700s, the American Colonies were showing signs of stress with Great Britain, and wanted to be seen as different. So famed statesman Benjamin Franklin devised a way to help Americans set themselves apart—with a brand new alphabet. The alphabet was to have been based on sound with consonants such as “Ch” and “ng” being paired together to form single letters.

After the proposal in 1768, a few schools adopted it out of curiosity. While it seemed to be doing okay for a couple of years, the Revolution suddenly hit. With everyone out fighting, the reform was forgotten. In the end, Franklin’s English was forgotten and lost until its rediscovery over a century later.

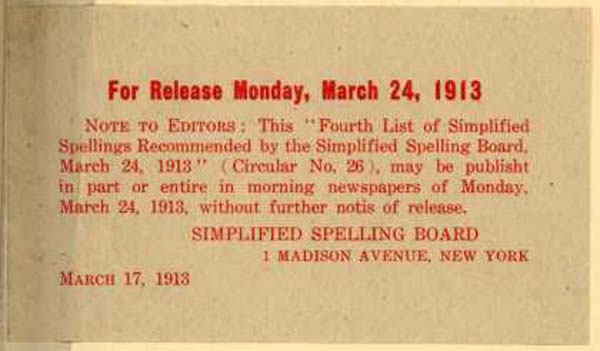

In 1906, Scottish-American steel magnate Andrew Carnegie teamed with President Theodore Roosevelt with a simple goal: to create a simplified spelling of the English language. Aiming at making it easier to understand, they planned to drastically reform English spelling. For example, under the Simplified Spelling Board, words like “kissed” and “bureau” would become “kist” and “buro,” with many word being spelled with different letter pairings, such as the word “cheque” becoming “check”.

Amazingly, the idea was introduced into schools and government letters in the early 1900s. After numerous complaints and public outcry, it went before the supreme court—its only language case—and a stop was put to it. While Simplified Spelling ended around 1920, a few remnants snuck their way into everyday usage, such as the dropping of the letter ‘u’ from words like “colour” and “parlour.”

After being kicked out of New York, Ohio, and Illinois, Mormons—AKA, the Church of Latter Day Saints—headed off to Utah. Once getting there, the settlers decided to make the land their own complete with plans that included making their own writing system. The system—known as Deseret—was created to make learning languages easier as it comprised one set of writing characters for all languages, as opposed to the regional specialties of most.

Soon enough, books were printed in Deseret and schools began teaching it instead of Latin letters. Even government documents and coinage were produced in the new script. However, Deseret screeched to a halt all because of one thing: the library. Since all the books in the Mormon library were in English, they would need to replace them at a cost of over one million dollars—a price that would almost bankrupt the church. Not willing to risk it, English lettering was brought back and Deseret was quietly put down.

Tamboran was the native language of southern Indonesia for over 1,000 years. It was an unusual language as it was not in the same family as its surrounding languages. By 1815 there were thousands of speakers in a series of communities in Tambora.

That is until a volcano right next door erupted. In 1815, Mt. Tambora was the largest eruption in 900 years. It devastated crops worldwide with its ash blackening the skies, and it sent pumice flying as far as Calcutta. Tambora also killed most Tamborans, making it the only language ever to be eliminated by a Volcano.

Evan V. Symon is a moderator at Cracked.com, whose work can be viewed here