Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Times When Species Evolved Backward

Facts

Facts Ten Unexpectedly Fascinating Facts About Rain

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of Australia’s Gruesome Unsolved Wanda Murders

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Space

Space 10 Asteroids That Sneaked Closer Than Our Satellites

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Times When Species Evolved Backward

Facts

Facts Ten Unexpectedly Fascinating Facts About Rain

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of Australia’s Gruesome Unsolved Wanda Murders

10 Subjects That Should Be Taught At School

The current “core curricula” of public schools in the US are comprised of the following subjects: (sciences) biology, physics, chemistry; (mathematics) arithmetic, algebra, pre-calculus, basic statistics; (language) literature, humanities, composition, foreign languages; (social sciences) history, government, economics, basic political science; (physical education) baseball, basketball, football, general exercise

Here are ten other subjects that all students from the ages of six to eighteen should be required to study:

Ask any elementary school student, and he or she will affirm that making up stories is fun. And since Stephen King is quite wealthy from doing so, education and practice in fiction composition is not irrelevant to society. College students across all majors admit that fiction writing courses, whether electives or required, are among their very favorite. After all, you finally get to write what you want to write, not some tedious, insipid essay about how Holden Caulfield is some brooding intellectual, an essay thoroughly devoid of anything interesting precisely because your teachers require you to examine the facts and draw your conclusions like a robot.

Hamlet can teach us a wealth about morality, human nature, existentialism, and politics. Shakespeare is showing us what happens if we give free rein to vengeance: our whole lives and those of all who are close to us are destroyed. When students in high school finish reading Hamlet—provided they have good teachers who can help them understand and appreciate it—most of them are sufficiently enthralled to try writing fiction—as well they should be. But most of them give up when their first stories turn out to be less great than those of Shakespeare. This is not due to middling talent, but an absence of instruction in fiction writing.

Why not? Students are typically thought of as having naturally gifted minds for either liberal arts or math—but rarely both together. That’s probably not true, however. Pure mathematics prompts the liberal arts-minded to ask, “What in the world is the point?” In public school, students aren’t forced very often to apply mathematics to their daily lives. Those word problems about Trains A and B leaving the station don’t help at all. So let’s talk calculus: why is it such a great thing to know?

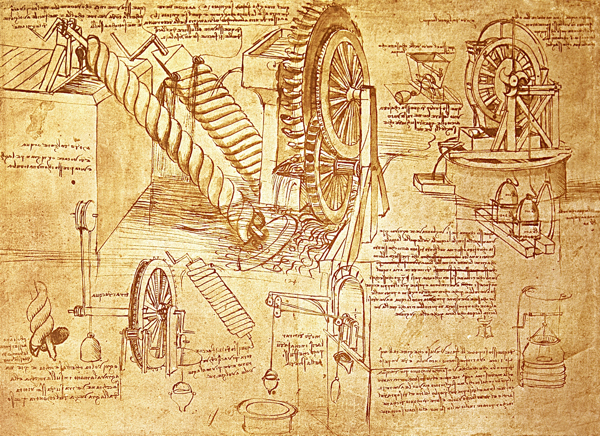

This will sound ridiculously ironic, but Newton and Leibniz invented calculus as a means of making geometric and algebraic operations easier. Johannes Kepler plotted the courses of the sun and the planets, and hypothesized that a sort of weight must hold them in orbits around each other. It took him about twenty years to do this, largely by watching the night sky through a telescope. Newton did all this in a single afternoon—thanks to calculus.

Calculus, as it should be taught, is the study of change with the aim of predicting it. Sounds a little cooler that way, doesn’t it? You can predict the future with calculus. But what could be more dull than algebra and pre-calculus in high school? Not much, if the teaching is conducted entirely theoretically. It would be a fine idea to give the students some hands-on experience inventing gadgets—using technology for what it does well, instead of merely learning about it on a chalkboard. Who wouldn’t want to invent a time machine? “Can’t be done,” you say? Well, it can still be a lot of fun trying, and in the process you’ll enjoy seeing just what the higher mathematics are capable of doing.

Many public schools do offer drama classes as electives—but these usually focus on stage performance. As important as it is for any serious actor to know how to act in live shows, many of these students would very much like to try their hands at making motion pictures, yet don’t have an outlet for it.

A lot of high school students would love to be directors, and most of them idolize Steven Spielberg. He’s about as close to god as you can get in Tinsel Town. Spielberg did not formally study filmmaking until college. But imagine how much faster he would have progressed in his filmmaking abilities, had he been able to receive instruction in middle or high school.

To be fair, geniuses of his caliber are typically self-taught—but proper instruction from a good teacher, along with diligent study, are far more reliable and desirable than raw talent and trial and error. For the mere mortals among us, enrolling in a filmmaking class in middle or high school is the most logical choice if we wish to pursue the dream. Such enrollment also offers us a fair chance of getting noticed by any of the bigwig connections the instructor may have.

Forget Spanish. Forget French. Spanish is particularly important to learn, but students have plenty of time to do that in college—and frankly, the amount of linguistic instruction they receive in high school doesn’t really prepare them for a collegiate education in that language. This lister chose French in high school because it sounded more beautiful—but by the time college rolled around, he had forgotten about eighty percent of it. When he took College French level one, the first half of the course was effectively a refresher of high school. So is it a waste of time trying to learn a language before college?

Not necessarily. Latin is bit more difficult than French or Spanish, but not by much. Of all the Romance languages, Italian is probably the trickiest—but if you’ve got a good foundation on Latin, any other Romance language will be a walk in the park.

This lister didn’t bother going back to French in college until he had four years of Latin behind him. Then he needed only one summer to master reading and writing French. Speaking it, of course, requires listening to it for a few years, but once you reach that point it’ll be locked in very well. So if the goal in learning foreign languages is to master as many as possible, why not start on one of the largest foundations available?

No, the lister isn’t looking for controversy on this one (hence, the word “multi-religious”). But many of us—whether still in public school or college, or out working for a living—remain in the dark about the finer points of most of the world’s major religions. Many of us would be hard-pressed to point out a New Testament verse against homosexuality, for example (it turns out there are three—and a possible fourth.)

If we are to have long, heated debates about the merits of this or that religion, or of having no religion, it is only fair that we should familiarize ourselves with the ins and outs of each—and we should do this in depth. Who do Shintoists worship? And why? What are the founding tenets of Satanism? If religion is such an integral and insoluble aspect of our species, it would be better if we understood the content of as many as we can learn.

We must be realistic about how much complexity and abstraction teenage students can be expected to digest and comprehend. In most schools, only one Shakespeare play per year is typical; the diction is too difficult and the literature too heavy to permit a full understanding of A Midsummer Night’s Dream or Othello in a single semester.

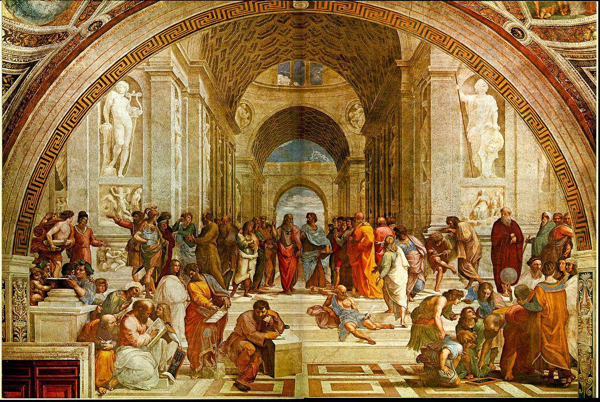

Philosophy—complex as its ideas may sometimes be—is very important and relevant to our daily lives. But it isn’t dwelled upon much at all in public school, most likely because the teachers don’t really understand it. Nevertheless, a fairly brief history of philosophy’s progression is certainly pertinent to life today. It will, at the very least, give the student a profound respect for the glory that was Ancient Greece.

All of Western politics, as well as a large portion of its history, can be traced back to geniuses like Zeno, the Seven Sages, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Eastern philosophy incorporates Confucius, Gautama, Mozi, Sun Tzu, and many others, all highly significant. To learn the history of philosophical thought, the student cannot avoid learning just a little about each school of it; and almost all new ideas are built on the backs of the old ones.

Public schools in the US require “physical education,” which simply means forcing the students to exercise for a little while on a daily basis. But the sports to which they’re treated vary considerably: dodgeball, basketball, track and field, calisthenics, and so on. They are not required to learn all the rules of basketball; they just have to take their place in the group (sometimes being chosen last) and run around for an hour or so.

Those who wish to really learn basketball can try out for the team, but they’re not likely to be accepted unless they’ve already developed the necessary skills. Sport (as opposed to P.E.) is not a requirement of many curriculums, but if students had to play at least one sport during middle school and high school, they would all become much more physically fit—and happier at the prospect of not being chosen last.

Most of us are at least vaguely aware of the moves of the game, while those with any impressive aptitude for it number perhaps 150,000 in the United States. There are only about 1,000 International Grandmasters in the world. Chess organizations, like the US Chess Federation, or the International Federation of Chess (FIDE), employ rating systems to show a player’s approximate skill level. The average novice plays at about 500, while the average veteran tournament player might be rated anywhere from 1000 to 2200. Grandmasters must be rated 2500 or more at least once to get the title. These days, the world champions are usually rated around 2800.

Above are plenty of examples of what makes chess fun—in particular, the possibility of feeling a sense of constant improvement—but they leave out the most important one: chess is a great tool for exercising the mind. The regular and serious chess players almost always perform better on tests in any subject area, because they’re used to sitting patiently, looking for the right answer, and especially thinking critically.

When you lose at chess, you have only yourself to blame—and provided that they have a good instructor, students between the tender ages of five to eighteen can find in chess an excellent source of humility, duty, responsibility, and fair play; in short, chess enables them to mature much faster.

Not just good music—like Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven—but all the way down to Justin Bieber, if that’s what you want. To be proficient in musical history is of prime importance. Music is already taught in public schools, but it isn’t required. It’s an elective, and sadly, it’s often the first subject on the curriculum to be cut when money is tight. But what is the purpose of learning to read and write if you aren’t given anything to read or write about? In history class, you may get a single paragraph or just a sentence about Beethoven—perhaps even a picture—but no attention is paid to what “sonata-allegro form” means. Most high school students graduate knowing loads about WWII, and virtually nothing about Rachmaninoff.

The problem, of course, is that you can’t really teach music without making the student perform it. You don’t learn to play the violin by reading a manual, and you don’t become truly familiar with exposition, development, recapitulation, and coda until you’ve listened to many examples of it. Only then will students appreciate the complexities involved in its composition.

This is set apart from sports in general, since we think of sports in public schools as consisting of baseball, basketball, football, track and field, and so on. But martial arts should be taught not as a regular sport, but as a means of self-defense. It would certainly put a stop to bullying. Most fights these days go the bullies’ way, since they are almost always bigger and stronger; that’s why they’re bullies.

And some of the bullied outcasts—whether nerds, goths, or generally “unsociable”—resort to firearms, in order to give themselves some desperately needed relief from the agony of bullying. The real shame in all this is that fighting a larger, stronger person really isn’t that difficult. You just have to know how to do it—and anyone can learn anything, given the time. The first step to winning a fight is to attain confidence in oneself. With confidence comes that magic knowledge of when name-calling has gone far enough. But you won’t attain that confidence until you know how to fight.

Unfortunately, many of the jerks we have to put up with also learn martial arts, just to be even crueler. But martial arts are a great equalizer, and they also tend to have the effect of reducing, rather than increasing, the violent impulses in children. We should therefore consider starting lessons while the students are still in elementary school.

FlameHorse is a writer for Listverse. None of the above subjects were ever offered during his public schooling.