Food

Food  Food

Food  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Our World

Our World Top 10 Real Almost‑Cities That Never Materialized

Technology

Technology 10 Unsettling Ways Big Brother Is (Likely) Spying on You

Music

Music 10 Chance Encounters That Formed Legendary Bands

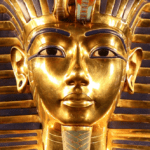

10 Creepy Omens That Foretold a Royal Death

Humans have always had a gnawing anxiety about when they will die. Dealing with this uncertainty may perhaps be the reason why cultures around the world imagined that there are things that can predict approaching death: certain animals, dreams, natural phenomena, strange behavior, and odd events. Since ancient times, death omens have included black cats, crows, owls, and solar eclipses.

The old royal dynasties of Europe had their own portents of misfortune, usually a spirit attached to the family. This may be a survival of the idea of tutelary spirits—the Greek “daemon” and the Roman “Genius”—guardian entities that guide, protect, and warn. White Ladies abound in folklore. In Ireland, she is called the Banshee, the spirit of someone who in life was either a friend or an enemy of a certain family. Depending on the connection, the Banshee either sings a song of comfort at a family member’s impending death or else lets out a gleeful, vengeful shriek.

This list will focus on royal deaths that had a significant impact on history and the legends of the omens that purportedly predicted them.

Related: 10 of the World’s Most Cursed Gemstones

10 Alexander’s Crown

The sudden death of Alexander the Great in Babylon in 323 BC at the young age of 32 remains a mystery. Malaria, typhoid, and murder by poison have all been put forward as likely causes. Whatever may have killed the Macedonian conqueror, his death was preceded by omens that hinted at his fate.

In Babylon, Alexander was steering a boat with some companions through a malaria-infested swamp where legends said the old Assyrian kings lay buried. A strong wind suddenly blew Alexander’s beribboned hat away, and it got entangled among some reeds. One of the men braved the waters and jumped overboard to retrieve it. To prevent it from getting wet, he placed it on his own head.

If Alexander knew of the old prophecy that foretold doom when “another head, except that of the king, would wear his diadem,” it certainly didn’t seem to have bothered him. After all, the hat wasn’t exactly a diadem. But the next incident was more ominous.

One day, when Alexander was out of the royal palace in Babylon, an escaped prisoner sneaked in, sat on the throne, and crowned himself with the diadem. He was caught and claimed that he escaped with the help of a “supreme god” who told him to do what he did. The prisoner was executed, but Alexander was unnerved by the events. He became distrustful of those around him, fearing a conspiracy against his life.

On May 29, 323 BC, Alexander had a lot to drink and came down with a fever the next day. He continued to deteriorate and died eleven days later. Murder or natural causes? The debate goes on.[1]

9 A Dream of Jupiter

Unsurprisingly, the cruel and perverted Roman emperor Caligula was the target of many assassination attempts. Suetonius narrates that before the one that finally did him in, many omens were reported that hinted at Caligula’s fate.

A statue of Jupiter that was being prepared for transport to Rome reportedly burst into laughter, terrifying the workmen. The Capitol at Capua was struck by lightning on the anniversary of Julius Caesar’s murder, which some saw as a portent of another imperial death. Lightning also struck the doorkeeper’s lodge at the palace in Rome, a sign that disaster was at the door for the palace’s occupant.

Caligula was sufficiently rattled to consult a soothsayer, who told him to expect death soon. “Beware of Cassius!” the Oracle of Fortune at Antium also warned him, after which Caligula ordered the murder of Cassius Longinus, governor of Asia. But Caligula couldn’t escape his doom. One night, he dreamed he was standing in Jupiter’s presence in heaven when the king of the Gods kicked him back down to Earth.

The next day, January 24, AD 41, the blood of a flamingo Caligula was sacrificing spattered him. It was also portentous that the tragedy of Cinyras, the very play being watched by King Philip of Macedon when he was assassinated, was being performed for Caligula at the theater. When Caligula left his seat for midday lunch, he was pounced upon by his own Praetorian Guards along the narrow passageway to the palace and stabbed multiple times.

What was the name of the Guard’s colonel who led the assassins? Cassius Chaerea.[2]

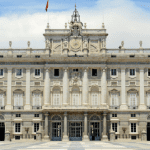

8 The Red Man of the Tuileries

In France, legend tells of a little man dressed in red who appeared in the Tuileries Palace before some royal calamity. One version of the tradition says that L’Homme Rouge was the ghost of a butcher executed on the orders of Queen Catherine de Medici in the 16th century. Another says he was a demon who first revealed himself to the queen and dwelt in the central tower used by the queen’s astrologers.

With the palace still under construction, the creature told Catherine that she would die near St. Germain. As the Tuileries was in the parish of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, Catherine abandoned her dream palace in terror. From that time, Catherine refused to set foot in St. Germain, even avoiding the bridges that might take her accidentally to the vicinity.

One day in 1589, she came down with an illness while staying in a hotel near Saint-Eustache. As she grew worse, a Benedictine monk was summoned to give the last rites. Catherine asked his name. It was Laurent de Saint Germain.

The Red Man was also seen on the three nights before the assassination of Henry IV in 1610. In early August 1793, Queen Marie Antoinette and her attendants were lounging in the Salie des Gardes when they spotted an impish man in red staring at them with such malevolence that they fled in fear. This was followed after a few days by the start of the French Revolution when Marie and King Louis XVI lost their thrones and their heads.

The imp was also said to have guided Napoleon’s career and was seen before the death of Louis VIII in 1824. His last appearance was in 1871, during the uprising of the Paris Commune when the Tuileries was burned to the ground.[3]

7 Catherine the Great’s Doppelganger

Doppelgangers, phantom doubles of living persons, have traditionally been omens of misfortune or death to anyone who sees theirs. Though the term is German for “double-walker,” doppelgangers were familiar to ancient Egyptians as the “ka,” to the Norse as the “vardøger,” and to the English and Irish as the “fetch.” Queen Elizabeth I was reported to have seen herself lying on her bed “pallid, shivered, and wan” a few days before her death on March 24, 1603. A century later, we have another royal encounter with the sinister doppelganger.

Catherine the Great was Russia’s headstrong czarina who led her nation into a golden age. The legend goes that one night in 1796, Catherine’s confused attendants came into her room as she lay in bed, saying that they had seen her, or someone who looked like her, enter the throne room. Catherine, probably more angry than alarmed that someone was impersonating her, hurried to see for herself. Upon the throne was seated her exact double. Enraged, the czarina ordered her guards to shoot. The bullets passed harmlessly through the apparition, which suddenly disappeared.

A few days later, Catherine collapsed from a stroke and fell into a coma. Less than 24 hours later, on November 17, she was dead at age 67.[4]

6 The Joke That Came True

On June 29, 1782, Catherine’s son, Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich and his wife Maria Feodorovna were having dinner with friends in Brussels. The group amused themselves by telling stories about scary experiences they had. Pavel recounted that one night, a stranger in a cloak and hat accosted him on a street in St. Petersburg.

The man, who emanated a deathly coldness, told Pavel, “I am the one who takes part in your destiny and who wants you to be especially unattached to this world because you will not stay in it for long.” Pavel explained to his hushed audience, “It means that I shall die young.” Afterward, he admitted to one of the party, the Baroness d’Oberkirch, that it was all a joke and made her promise not to mention it anymore.

Upon Catherine’s death, Pavel succeeded her as Czar Paul I. On March 11, 1801 (Old Style), Paul was having dinner with his inner circle when he turned to look at himself in the mirror. The mirror’s defect distorted his image, and Paul remarked, “Look how funny the mirror is. I see myself in it with my neck turned on the side.” He began to talk about death to General Mikhail Kutuzov. “Going to the other world isn’t sewing pouches,” were his parting words to the general.

About an hour and a half later, assassins broke into the palace and invaded Paul’s chambers. A scarf was wound around the emperor’s neck, strangling him. Paul was dead at the young age of 47. In her memoirs, Baroness d’Oberkirch remembered Paul’s “joke” that night in Brussels, a joke that tragically came true.[5]

5 White Lady of the Hohenzollerns

Countess Kunigunde of Orlamunde was a young widow from the 14th century whose love for Albrecht of Zollern ended tragically, especially so when she murdered her two children, whom she mistakenly thought disapproved of the relationship. After her death, she still haunts the Hohenzollern family as a harbinger of death for the male members of the family, perhaps as revenge for her rejection.

Through the centuries, the Hohenzollerns dreaded her appearance. In one incident, King Frederick I of Prussia fell ill from terror on seeing a white-clad woman enter his room and died shortly afterward. The woman he saw only turned out to be his wife, Sophia Charlotte. But the most frightening appearance of the White Lady was in July 1857 at Pillnitz Castle in Saxony, where King Frederick William IV and the queen were visiting their cousins.

At about one in the morning, a palace sentry saw a woman in white leading a spectral procession of five men. The sentry was paralyzed with terror upon seeing the men were headless and carrying a coffin. The ghostly procession entered the palace by a side door. When it reemerged, the sentry could see that the open coffin now contained a headless body. It was wearing Prussia’s Order of the Black Eagle. Where the head should be, there lay the royal crown, illuminated by the moonlight. The White Lady led the group away from the palace and disappeared.

Frederick William was still in Pillnitz when he began to experience the first symptoms of the illness that would eventually take him. Three months later, in October, he suffered an incapacitating hemorrhagic stroke. He turned over the reins of government to his brother, Prince William, while he slowly deteriorated into madness. King Frederick William was finally released from his sufferings by death on January 2, 1861.[6]

4 Black Lady of the Wittelsbachs

The ancestral castles of Fürstenried and Nymphenburg in Bavaria are haunted by the Wittelsbach family ghost, an old white-haired woman in a long black medieval dress who announces the coming death of one of its members.

One spring day in 1864, a small luncheon was being hosted by King Maximillian II and his wife, Marie of Prussia. As the meal progressed, Marie looked up at her husband sitting opposite her and saw a woman in black standing behind the king’s chair, gazing sorrowfully at her. Marie gasped, and the apparition vanished.

She then told Maximillian what she had seen. Knowing what the vision meant, the king angrily demanded that the guards at the door tell him who let the stranger in, but the guards denied allowing anyone access. Maximillian explained to his startled guests that his wife must have been hallucinating. Three days later, on March 10, though in robust health, Maximillian suddenly fell ill and died. The cause was thought to be gastritis.

Maximillian was succeeded by his son Ludwig, the notorious “Mad King” of Bavaria. One June night in 1886, a sentry saw a woman in black gliding along the king’s corridor. He chased the phantom down the stairs into the courtyard, where he challenged her to identify herself. The Black Lady continued on in the moonlight without a word but turned to face the guard as she was about to enter the chapel. The rattled sentry shot at her, but the gun backfired, mortally injuring him. He barely managed to tell his story to other responding guards before he died.

The next day, the 13th, King Ludwig and the doctor who pronounced him insane were found dead on the shallows of Lake Stamberg. The doctor showed signs of violence. It was presumed that Ludwig drowned, but his lungs held no water. To this day, the Mad King’s death is still a mystery.[7]

3 White Lady of Hofburg

A little past midnight on April 24, 1898, the sentry at Vienna’s Hofburg Palace saw a strange woman in white carrying a candle glide toward him. Upon being challenged, the woman retraced her steps and entered the chapel. A thorough search failed to uncover any traces of the stranger. An hour later, a similar incident occurred in Schonbrunn Palace, a summer residence of the Imperial family.

The sentry did not know it, but he had seen the White Lady of Hofburg, the Habsburg family ghost who had traditionally portended an imperial death. It had last appeared on January 30, 1889, before the news of the murder-suicide of Crown Prince Rudolf and his sweetheart, Countess Marie Vetsera, broke upon the anguished Emperor Franz Josef and Empress Elizabeth.

Elizabeth, affectionately called Sisi, already trapped in a troubled marriage, could no longer cope with the death of her only son. She betook to wandering incognito across Europe in an effort to escape her despair. Five months after the sightings at Hofburg and Schonbrunn, Sisi twice saw a woman in white give her a malevolent stare as she vacationed in Switzerland.

On September 10, 1898, Sisi and her lady-in-waiting were about to board a steamer to take them across Lake Geneva to Mont de Caux when an anarchist, who had been shadowing Sisi, suddenly sprang up and drove an awl into the empress’s breast. Sisi was able to stagger onto the ship but soon succumbed to internal bleeding.[8]

2 The Turnfalken

The White Lady was not the only death omen to bedevil the Habsburgs. Many family deaths, some quite unexpected, were announced by a flock of eerie birds called Turnfalken. They were said to be nocturnal creatures, flying only in the daytime to forebode ill tidings to the family with shrill cries.

Legend makes them out to be supernatural ravens out for revenge on the dynasty. Around AD 1000, ravens were said to have saved an ancestor from being torn to pieces by vultures. In gratitude, he built a tower in the forest as their sanctuary. But a hundred years later, another Habsburg built his castle on the site, chasing the ravens away and killing some. From then on, as the sinister Turnfalken, the ghostly ravens began to appear before any misfortune or death came to the family.

They were seen hovering as Marie Antoinette was being led to the guillotine before Franz Josef’s younger brother, Emperor Maximillian, fell before a Mexican firing squad in 1867. They were also seen before the deaths of Rudolf and Marie’ Sisi’s sister Sophie Charlotte, Duchess d’Alencon, in a fire at a Paris bazaar in 1897; and of Sisi herself. The day before her murder, a huge raven swooped down on Elizabeth, knocking a peach out of her hand.

One June day, Duchess Sophie of Hohenburg was riding in her car when she saw an excited crowd pointing up the sky. Ordering her driver to stop, she tried to see what the spectacle was. Sophie recoiled in horror. Turnfalken! She rushed to warn her husband, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, against going ahead with their planned trip to Sarajevo. Franz Ferdinand could not be dissuaded despite her pleas. On the fateful 28th of that month, 1914, he and Sophie were gunned down in Sarajevo.

This time, the Turnfalken had predicted doom not only for the Habsburgs but also for the world. The assassination of Franz Ferdinand was the spark that ignited World War I.[9]

1 The White Stag

The Turnfalken were not the only animals to warn of Franz Ferdinand’s appointment with Death. Around the world, it is considered bad luck to shoot a white deer. In Germany and Austria, hunters still believe that anyone who does so is cursed, and he or a member of his family wiłl die within a year.

Franz Ferdinand loved to hunt animals. His bloodlust was such that he estimated that he killed nearly 300,000 animals, enjoying both single kills at a time as well as mass slaughter. He was a superb shot and relished having his victims driven into a funnel toward him, where he could mow them down. In 1913, Franz Ferdinand didn’t think twice about shooting down a rare white stag, curses be damned.

Also around this time, the expansion of the imperial crypt in Arstetten, which had been commissioned in 1908, was completed, and it was ready to receive the bodies of the Archduke and Duchess Sophie. This must have weighed heavily on Franz Ferdinand’s mind, and by late June 1914, he was “extremely depressed and full of forebodings.” He had confided to a relative in May, “I know I shall soon be murdered.”

There were so many things that Franz Ferdinand could have done to avoid death in Sarajevo. But the run of bad luck that day gives the impression that the Archduke, like his animal victims, was being funneled by an unseen hand toward Gavrilo Princip’s gun and his doom. He could have chosen any day for his visit other than the 28th, the memorial day of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo for patriotic Serbs.

He could have confined himself to the review of military maneuvers at Ilidza, the primary reason for his trip, and not gone into Sarajevo at all. He could have heeded the danger after he escaped the bomb thrown at him on the way to City Hall. Instead, he left the safety of the building to visit the wounded from the bombing. But no one told the driver of the new itinerary, and he made the wrong turn—straight to where a surprised Princip was standing.

Was it the curse of the white stag? Or just terrible luck? Eerily, Franz Ferdinand’s death car had the license number A111-118. Which might have been predicting Armistice Day 11/11/1918. Or maybe not.[10]