Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

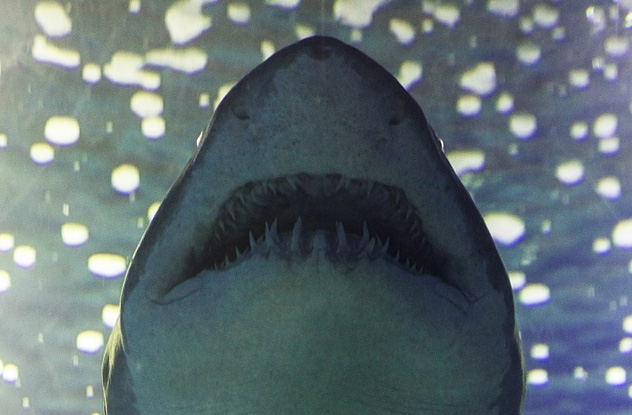

10 Crazy Ways Sharks Will Amaze You (If You Don’t Get Too Close)

Sharks aren’t warm and fuzzy, cuddly type animals. Despite the dangers, we keep trying to get close enough to study them because they’re absolutely fascinating. However, even shark embryos will bite you if you’re not careful (as renowned shark biologist Stewart Springer discovered while dissecting a pregnant sand tiger shark in 1947). The more we learn about sharks, the more they amaze us with some crazy characteristics that even scientists never expected to see.

10Some Sharks Are Small Enough To Fit In Your Pocket

A “pocket shark” is so small that you might mistake it for a more common, harmless fish if it’s swimming around you in the water. Although the pocket shark has rows of tiny, sharp teeth in its bulbous head, scientists aren’t sure how it feeds because they’ve never seen one in action. But the 14-centimeter (5.5 in) pocket shark seems to be similar to the cookiecutter and kitefin sharks, both of which take oval bites out of the skin of their prey when hungry. Cookiecutter and kitefin sharks like to eat large fish, marine mammals, and squid.

Even though the pocket shark is small enough to fit in your pocket, it’s actually named for the small opening (or pocket) above each of its pectoral fins. Scientists have no idea how the shark uses those openings. But it’s a bioluminescent fish, so it’s possible that the shark releases a bioluminescent fluid from its pockets to mislead its predators or to attract a mate.

Your chances of getting bitten by a pocket shark in the ocean are slim to nonexistent. Scientists have only seen two pocket sharks. Ever. This latest one was found in early 2015 off the coast of Louisiana. The last one was swimming in the waters around Peru and Chile 36 years ago.

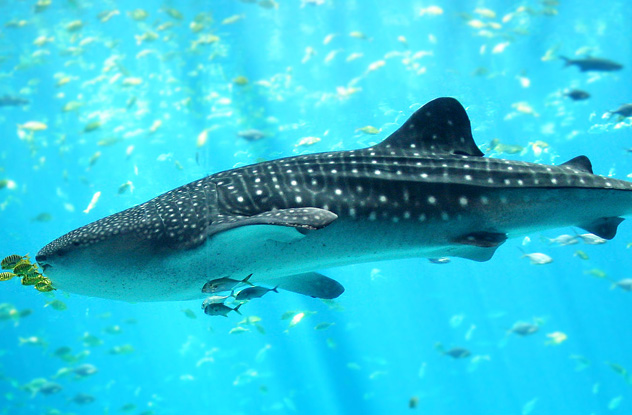

9Whale Sharks’ Patterns Are Like Fingerprints

The elusive 12-meter (40 ft) whale shark is the biggest fish in the ocean. It’s usually a loner that travels long distances for food in warm waters, so we haven’t located their nursery grounds. Whale sharks give birth to live baby sharks, or “pups.” This allows the baby to be protected longer within the mother’s body than fish that develop from larvae deposited in the ocean. However, fewer whale sharks are produced this way, which caps the speed at which their population can recover when threatened.

They sometimes congregate when feeding. They also have an odd yet beneficial relationship with the schools of tuna that follow them. When tuna circle prey like anchovies or sardines, the smaller fish form a close-packed “bait ball” to defend themselves. The filter-feeding whale shark uses that opportunity to stand on its tail, open its mouth, and suction the water and fish inside its body.

Perhaps the most interesting fact about the whale shark concerns the unique pattern of stripes and dots covering its body. A whale shark can be identified by its pattern like we’re identified by our fingerprints. This lets scientists observe their migrations to different areas of the world.

In fact, WhaleShark.org uses a NASA algorithm to match any new photos against its database of over 50,000 existing whale shark photos. The algorithm was originally developed to recognize individual stars in pictures taken by the Hubble Space Telescope.

8Sharks Have At Least Seven Sharp Senses To Help Them Find Prey

With at least seven acute senses, sharks can find prey even when that prey hides. Sharks can see colors and have better night vision than cats. Their excellent hearing allows them to detect low frequencies emitted as distress sounds by wounded or sick animals.

Depending on the substance, sharks can smell up to 10,000 times better than we can. Using its left and right nostril to determine the direction from which a smell originates, a shark can target the source by changing direction until both nostrils receive equal signals. Sharks react most strongly to scents emitted by wounded or sick animals, but they’re also sensitive to smells from predators and mates. About two-thirds of a shark’s brain analyzes smells.

With their strong sense of taste, sharks often do taste tests on new substances before deciding whether to gobble the entire thing. Their skin can detect touch and temperature, but they also use their pressure-sensitive teeth to identify objects.

Using jelly-filled pores (called the “ampullae of Lorenzini“) around its head and snout, a shark can sense electrical fields, such as the Earth’s geomagnetic field to help its navigation and the magnetic fields produced by predators and prey as their muscles contract. That includes the beating of a heart, so prey that hides or uses camouflage can still be detected. Inanimate objects like metal also produce electrical fields, which may explain why sharks attack divers’ shark cages.

Finally, sharks use their “lateral line system” and “pit organs,” which are their seventh and possibly eighth senses. The lateral line system is a fluid-filled canal, lined with tiny hair cells, that runs the length of both sides of the shark’s body beneath its skin and is connected by small pores to the skin’s surface. This lets the shark detect pressure changes from the water displaced by moving animals, with erratic vibrations drawing a shark to sick or wounded prey. The lateral line also helps the shark to navigate as it displaces water with its own movements.

Found in different places on the shark’s body, a pit organ consists of two toothlike projections covering a tiny pocket in the skin. Hair cells line the bottom of the pocket. Although scientists aren’t sure, the pit organ may detect changes in water currents or temperature.

7Blindfolding A Shark Or Plugging Its Nose Won’t Stop Shark Attacks

At the Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida, scientists studied how blacktip, bonnethead, and nurse sharks use their senses to find prey. These types of sharks live in different habitats, have different body structures, and use different hunting strategies. By observing the sharks in a specially constructed flow channel, the researchers wanted to discover how each species would react to having key senses blocked.

As a control, the scientists first had the sharks use all of their senses to catch their prey. Each trial was supposed to last 10 minutes, but some sharks were chowing down in under 10 seconds.

Then the researchers repeated the experiment, obstructing one sense at a time. To do that, they covered the sharks’ eyes with black plastic, plugged their noses, temporarily destroyed their lateral line receptors with antibiotics, or covered their electrosensory pores with insulating materials.

Although the various types of sharks relied on different senses to find their prey, the researchers were amazed by how often the sharks successfully adapted when one sense was blocked. They simply used their remaining senses to hunt their prey.

For example, the blacktip and bonnethead sharks captured their prey without using their sense of smell, but the nurse sharks couldn’t. Feeding in the dark, nurse sharks obviously need their sense of smell to recognize their prey hiding in cracks in underwater rocks. Blacktips and bonnetheads feed differently, so they can see their prey at close range even if they can’t smell it.

When the sharks couldn’t see, they had to get closer and use their lateral lines to detect water movements caused by the prey. But if the researchers obstructed the sharks’ vision and lateral lines at the same time, none of the sharks could feed. They needed more than their electrosensory systems to capture prey. When the scientists blocked only the sharks’ electrosenses, the animals were also unsuccessful most of the time.

Nevertheless, this gives us some hope that the harm from pollution to certain senses in a shark may be overcome if the animal can substitute its remaining senses to survive. But it’s bad news for humans. Wearing camouflaged wetsuits or taking other measures that focus on only one of the shark’s senses may not be enough to protect us from shark attacks.

6Eating Shark Fin Soup Could Give You Alzheimer’s

In 2013, Canadian researchers told us that about 100 million sharks were being killed annually, making it impossible for the sharks to repopulate fast enough. Most of the sharks are finned to make shark fin soup, a symbol of status and wealth in some Asian countries.

In US waters, shark finning is illegal, but the trade of shark fins is banned in only 10 states as of mid-2015. These measures were taken to help conserve shark populations, many of which are in danger of extinction.

But if that’s not reason enough to stop eating shark fin soup, maybe the fact that the fins contain a high concentration of a neurotoxin will sway some people. According to a 2012 study from the University of Miami, the toxin Beta-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) in shark fins has been linked to human neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, Lou Gehrig’s disease, and Parkinson’s. The highest amounts of BMAA were found in hammerhead, bonnethead, and blacknose sharks.

The effects of BMAA may combine with that of other neurotoxins such as mercury to become even more harmful. “A delicious bowl of shark fin soup, loaded with mercury, loaded with BMAA—yum, yum, yum,” said Deborah Mash, lead author of the study, to The New York Times. “I mean, come on. Who would feed that to their family?”

5Sharks Have Toothpaste Built Into Their Teeth

Like humans, many animals suffer from tartar buildup on their teeth and the gum disease that results from it. Humans are probably the most prone to cavities because of our high-sugar diets. But sharks don’t have these problems. While human teeth are covered with hydroxyapatite, a mineral found in bones, the enormous, terrifying teeth of sharks are coated in 100-percent fluoride, possibly giving them the healthiest teeth among all animals on Earth. It’s like having toothpaste built into their teeth.

In 2012, researchers from the University of Duisburg-Essen studied the teeth of shortfin mako sharks, which tear their prey’s flesh, and tiger sharks, which cut their prey’s flesh. Even though they feed differently, the two types of sharks had teeth with a similar makeup. Scientists believe that the fluoride coating is far less likely to dissolve in a watery environment than hydroxyapatite, better protecting a shark’s teeth from bacteria.

Even so, scientists did discover something surprising: Human teeth are just as hard as sharks’ teeth. If a shark’s teeth were made entirely of fluoride, they would be much harder than human teeth. But sharks have a softer dentin inside their teeth just like humans. “It seems as if the human tooth makes up for the less hard mineral [on the outside] by the special arrangement of the enamel crystals and the protein matrix, and ends up being as hard as a shark tooth,” explained the study’s coauthor Matthias Epple in an interview with Discovery News.

Sharks still have one big advantage over us in tooth health. When a shark loses teeth while catching prey or biting into metal, the teeth simply replace themselves. A shark may grow more than 30,000 teeth during its life, which is over 900 times more teeth than most humans have.

4Lantern Sharks Have That Special Glow For Love And War

Velvet belly lantern sharks glow one way to protect themselves from predators and another way to advertise for sex, almost like a neon sign in the red light district of the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. Only these sexy sharks glow blue.

At a mere 60 centimeters (2 ft) long, they’re small, so they’ve developed a novel way of protecting themselves against hungry predators. If a predator looks at a velvet belly lantern shark from above or from the side, that predator will see a hard-to-swallow meal with scary glowing spines that resemble lightsabers.

Some scientists believe that these bioluminescent sharks are the first fish to protect themselves against predators with light. The shark’s transparent spine has a row of cells along its dorsal fin that can produce light. According to a 2013 study, the lightsabers are visible from a moderate distance, which could scare off predators even though the light is too dim to attract prey.

In addition to lightsabers, these sharks use a complementary light strategy on the bottom of their bodies. By using their bottom light cells to exactly mimic the amount of light streaming into the ocean from above their bodies, the sharks avoid casting a shadow, effectively becoming invisible to predators from below.

Researchers believe that the sharks use a transparent “pineal window” on top of their heads to gauge the amount of light shining on them. Then the sharks make hormones to produce the same amount of light shining from the bottoms of their bodies.

These hormones control the intensity of the shark’s blue glow, which changes when the animal is looking for love in the deepest, darkest places in the ocean. According to a 2015 study, velvet belly lantern sharks light up the area around their sex organs when they want to mate. That way, the males can signal for sex while being able to tell the difference between male and female sharks in dark waters.

The males have two sex organs called “claspers.” But scientists have never seen these sharks mate, so no one is sure what they do. However, researchers have seen the sharks rotating their bodies from side to side while they swim, which turns the pelvic light show into a series of flashes like those of a firefly. Scientists believe this is the shark’s way to confuse predators while attracting a mate.

3Sharks May Be Self-Aware

The late Donald Griffin, who pioneered the study of self-awareness in animals and how it affects their behavior, believed that an animal that hides itself from view is exhibiting self-awareness. Grizzly bears often watch hunters from areas where they won’t be seen. They also try not to leave tracks. It shows that they know others can watch for and see them.

In a similar way, Ila France Porcher, a self-taught ethologist and wildlife artist who wrote The Shark Sessions, believes that sharks exhibit self-awareness. Once called “the Jane Goodall of sharks” because she learned to study these animals in their natural habitat, Porcher repeatedly observed sharks in Tahiti using the visual limit—the shortest distance where neither you nor the shark can see each other—to hide from her. She also noticed that sharks had different personalities, and various species responded to her presence in different ways.

In general, once a shark became aware that Porcher was in the water, it would momentarily appear at the visual limit and then hide again. After a few minutes, the shark might come about for another look. If it wanted to explore further, it would come nearer, eventually approaching from the front. Then the shark either swam near her or quickly headed away.

To keep from being seen, the sharks often approached when she was looking in another direction, when her attention was absorbed by something else, or when her head was above the surface of the water. They came from behind as well. Porcher noticed that the sharks seemed to be acutely aware of when they were visible and when they could hide, taking advantage of their stealth whenever possible and hiding behind the visual line when frightened. These sharks often followed her for hours, mostly staying just out of view. Porcher believes that the sharks were using their hearing and lateral line system to monitor her.

When she saw reef sharks at sunset, she noticed that the young males came straight for her, but the shy, older females stayed out of sight for long periods, occasionally coming into view but never getting close to her. The sharks also seemed to anticipate some of her behaviors. For example, after hiding for hours, the sharks zoomed in for food when they heard Porcher getting a treat from her boat and tossing it toward the water.

2Shark Embryos Play Dead After Detecting Predators’ Electric Fields

When a shark is born, it has all the fully developed senses it needs to detect prey and predators. But doctoral student Ryan Kempster from the University of Western Australia decided to find out if a shark’s electrosense works while it’s still an embryo.

Although many sharks give birth to fully formed pups, some species lay eggs in leathery egg cases called “mermaid’s purses.” One embryo inside each egg case develops into a baby shark over several months independently of its mother. For his study, Kempster obtained 11 brown-banded bamboo shark embryos that were still in their egg cases. These embryos were about 90-percent developed, with only about one or two months left before they would emerge from their egg cases. As adults, brown-banded bamboo sharks are usually about 1.2 meters (4 ft) long.

Before then, however, the embryos are vulnerable to attacks from predators. Usually, a bamboo shark fetus circulates seawater through its egg case by beating its tail. Those currents, the odor from the shark, and the electrical field produced by the movement of the embryo’s gills as it breathes can alert predators to the presence of the fetus.

Researchers stimulated the embryos with electric fields like those of predator fish to see how the fetuses would respond. Surprisingly, the embryos detected these electric fields, suggesting that their electrosenses work even before they’re born.

But more amazing was their survival instinct. The embryos held their breath to stop their gills from beating and stayed absolutely still. The embryo cloaked itself, according to neuroecologist Joseph Sisneros in an interview with National Geographic. “[It shut] down any odor cues, water movement, and its own electrical signal,” he said. That behavior makes it harder for a potential predator to find the egg case and gives the fetus its greatest chance of survival.

However, the sharks became conditioned to the electric stimuli over time and eventually reduced their responses. For humans, this means that shark repellent devices will lose their effectiveness over time as sharks begin to recognize the signals.

1Sand Tiger Shark Embryos Eat Each Other In The Womb

For sand tiger sharks, survival of the fittest begins in the womb. Actually, in two wombs.

Each female sand tiger shark has two uteri, from which it produces one live pup per uterus with each pregnancy. The female always mates with at least two males, which is common for large sharks. The sand tiger grows to about 2.5 meters (8.2 ft) as an adult. Its babies are already a whopping 1 meter (3.3 ft) long when they’re born, which protects them from all but the largest predators.

But there’s a reason why two sand tiger pups are born so large: They eat their siblings in their respective wombs, so the surviving babies can grow much bigger and stronger than if they had to share food with their brothers and sisters.

After the female sand tiger shark has sex, its fertilized eggs end up in one of its uteri. The first male to mate with the female often sticks around to stop other males from having sex with her. But the female sand tiger shark has a long ovulation period. Eventually, she will mate with other males, and her dozen or so fertilized eggs in each uterus will have different fathers.

But the competition for dominance continues in the womb among the different fathers’ embryos. In each womb, the first embryo to hatch from its egg is usually the one that uses its tiny, sharp teeth to cannibalize its siblings in utero. It can eat their remains and the yolks from their eggs to nourish itself and grow quickly. After this, the mother doesn’t produce more embryos, but she will produce unfertilized eggs for the hungry surviving embryos to eat.

Interestingly, the two survivors often have the same father. These stronger babies also have a greater chance of passing on the mother’s genes to the next generation.