Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Creepy

Creepy 10 Shocking Tales of Bodies Found in Abandoned Houses

Politics

Politics Top 10 Surprising Facts from the Life of Jimmy Carter

Sport

Sport 10 Popular but Terrible Goalkeepers

Technology

Technology The 10 Most Compelling Aircraft That Didn’t Succeed

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Ridiculous Riffs on Robin Hood

Technology

Technology 10 Extreme Structures We Might See in the Future

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Catastrophic Translation Fails in History

History

History 10 Wild Facts About the Mutiny on the HMS Wager

Our World

Our World 10 Secrets Places You Won’t Believe

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Fascinating Origins of New Year’s Eve Superstitions

Creepy

Creepy 10 Shocking Tales of Bodies Found in Abandoned Houses

Politics

Politics Top 10 Surprising Facts from the Life of Jimmy Carter

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Sport

Sport 10 Popular but Terrible Goalkeepers

Technology

Technology The 10 Most Compelling Aircraft That Didn’t Succeed

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Ridiculous Riffs on Robin Hood

Technology

Technology 10 Extreme Structures We Might See in the Future

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Catastrophic Translation Fails in History

History

History 10 Wild Facts About the Mutiny on the HMS Wager

Our World

Our World 10 Secrets Places You Won’t Believe

Top 10 Dark Moments In The French Monarchy

To start, I have no significant qualms about constitutional monarchies. Truthfully, I find some value in giving a population a figurehead to rally around as well as in the benefits of training someone throughout his or her life to become such a leader. Absolute monarchies, by contrast, are much more problematic. In French history, while a constitutional monarchy could have served to benefit the French people in the manner of say the modern Australian, British, Canadian, etc. systems of government, various incidents involving the French monarchy in some way or other helped to alienate certain segments of the population, expose tensions among various organs of government, reveal the dishonesty of particular members of the court, or showcase problems inherent in appointments not based on merit. Now, of course, the French Republic has its shameful moments as well (cough, “Reign of Terror,” cough), which is why I suppose one can see positives and negatives for any form of government. This list, however, emphasizes arguably the most astonishingly terrifying incidents that played a role in weakening the Bourbon monarchy. I do not claim that these are all the main causes of the revolutions of 1789 and 1830, although some clearly played a role in influencing these revolutions.

The incidents recounted below nevertheless did not exactly help endear the masses to the monarchy and can be considered among various other occurrences that brought about the series of revolutions that thus far has caused France to indeed remain a republic. There are lessons monarchs can learn from these incidents: do not persecute those with different religious beliefs, do not execute people in over the top manners, do not make a big deal claiming your representatives accomplished some heroic feat as slaying a beast prematurely, and do not make people captains of ships with limited naval experience, among other lessons. On a final note, France is one of my favorite countries to visit. I have a number of French friends and greatly admire many people and works of art from their history. So trust me that despite this list’s emphasis on several terrifying moments from French history, the country has many more lists worth of admirable achievements and has many breath-taking sites to see for anyone interested in visiting this remarkable country!

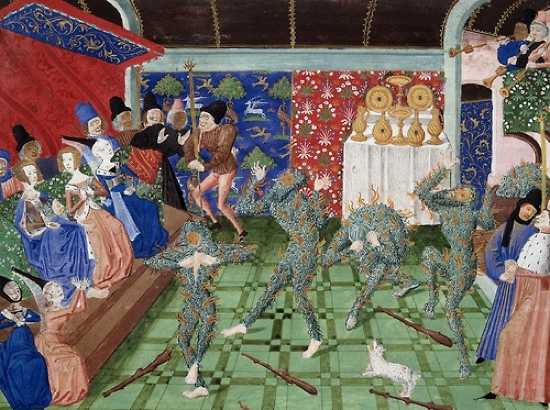

This notorious incident serves as an example of the problems of having an insane man as king. If the fourteenth century was not bad enough for the French with the Black Death, Great Schism, and Hundred Years’ War, the century also ended with a mentally unstable man on the throne. King Charles VI and several other men disguised themselves as savages during a masquerade hosted by Queen Isabeau. While wearing highly flammable attire, the king and his compatriots danced until a torch set them alight. Although a fifteen year-old duchess managed to save the king with her skirt, the queen merely fainted and all but one of the other faux savages died in the chaos. Meanwhile, Charles’s mental health continued to decline as to France’s position in the Hundred Years’ War culminating in the near collapse of the French monarchy roughly twenty years later at the Battle of Agincourt and the subsequent Treaty of Troyes by which Charles’ son was removed from the succession in favor of the English king. French fortunes only returned with St Joan of Arc’s successes in the later 1420s.

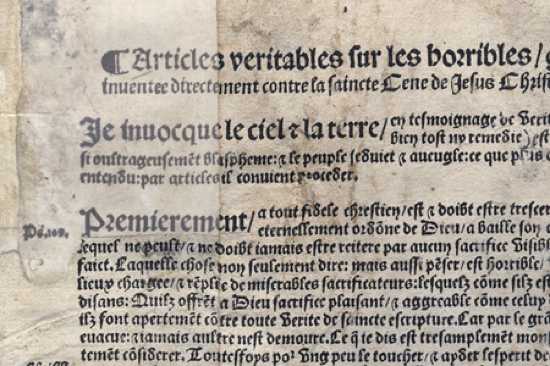

This affair resulted in a shift in Francis I’s policy from tolerance to the persecution of Protestants. The incident concerned the appearance of anti-Catholic and pro-Zwinglian posters in several major French cities, including on the door of the king’s bedchamber. French Catholics reacted as if greatly insulted, which in turn prompted leading French Protestants to flee potential reprisals. Francis ultimately issued a royal edict against French Calvinists known as Huguenots, which further divided France in the years leading up to the French Wars of Religion. These wars represented a loss of support for the monarchy among a significant segment of the population.

This example of religious intolerance and alienation of non-Catholics occurred during the French Wars of Religion. The blame for the incident from most historians has largely fallen on Catherine de Medici, mother of King Charles IX, although some historians, such as Denis Crouzet put greater emphasis on the king’s role in ordering the executions during this particularly tense phase of the Wars of Religion. Regardless of who was responsible, thousands were killed in the bloodshed as depicted in many famous artistic renderings by notable artists of the time. The French monarchy did find some support among their fellow monarchs for the massacre (chiefly from King Philip II of Spain), but when even someone named Ivan the TERRIBLE writes a letter in which he expresses his horror of the event, one gets a sense of how bad this particularly incident must have been! Indeed the violence between Catholics and Protestants in France and elsewhere in Europe only persisted in the coming years.

This time we have a famous woman as the victim rather than the possible instigator behind the atrocity. Moreover, we see an instance of religious persecution that was not one of Protestants versus Catholics, although it did occur during the time of the Thirty Years’ War that initially pitted mostly Catholic states against mostly Protestant states in its early years. Once again, if Europeans were not experiencing enough terror from a major war, they also descended into the tragedy known as the Great Witch Hunts. The execution of Anne de Chantraine is therefore an example of superstitious fanaticism that existed during the time of the Divine Rights Monarchs who reigned during the Thirty Years’ War and the Great Witch Hunts. This seventeen year-old girl was burned alive by state sanctioned authorities as a witch based on – as is usual in the cases of witch hunts – specious “evidence.” While she is one of many young women executed for witchcraft in early modern France, her fame has endured more so than many other alleged French witches due to her repeated appearances as a witch in the Atmosfear/Nightmare board game series.

The infamous story of this mysterious man serves as an example of absolute monarchy imprisoning someone under mysterious circumstances. What is known is that a prisoner known as Eustace Dauger served time in a number of prisons during the reign of King Louis XIV. The most notorious of his places of imprisonment was the Bastille, the famous target of French revolutionary ire nearly a hundred years later. Yet, beyond the bare facts, the circumstances of Dauger’s arrest and imprisonment have been the subject of much speculation and conspiracy theories and have made for major works of popular fiction including a not-too-distant cinematic portrayal of the man by acclaimed actor Leonardo DiCaprio. As for the man himself, speculation of who he was and why he was arrested ranges from a relative of Louis to a disgraced general to a whole host of other possible candidates.

Whereas Anne de Chantraine probably did not have supernatural powers that necessitated her tortuous execution, Madame de Brinvilliers, another alleged criminal during Louis XIV’s long reign, seems to indeed have been guilty of her crimes. Yet, unlike the man in the iron mask, this murderess has found little sympathy or support among her contemporaries and those who lived after her sentencing. Moreover, whereas the punishment of de Chantraine and Dauger may have made the state system seem arbitrary and harsh, the punishment of de Brinvilliers exposed the nobility as possessing the potential for committing scandalous crimes that one would hardly describe as “noble.” The consequences of this affair go further to damaging the position of the French monarchy, however. Here we have an example of a member of the nobility being a murderess, but this example is also significant for causing resentment of Eugene of Savoy against Louis XIV for the expulsion of his mother from France, which prevented him from having a successful military career there. He went on to defeat French armies in the decisive battle of Blenheim in 1704. Louis XIV would thus not be able to achieve the preeminent position in European – if not world – affairs that he spent decades trying to attain.

Yes, many bad incidents in French history seem to be named “affair” for some reason and so here is another! This particularly grotesque “affair” revealed apparent tension between the Parlement of Paris and the monarchy. The horrifying aspect of the event concerned how the authorities dealt with the man after which the affair is named. Robert-François Damiens (9 January 1715 – 28 March 1757) attempted unsuccessfully to assassinate his king, Louis XV, Louis XIV’s successor. After being first imprisoned, he was tortured in a variety of cruel ways, including the use of red-hot pincers on his body, various burning and boiling agents on his hands, and ultimately horses affixed to his limbs via ropes to dismember his body. Reportedly, the dismemberment did not go easily and so the executioner used an axe to finish the job. Witnesses claimed his torso somehow lived after all of that, at least until it was burnt alive! As Ohio State University scholar Dale Van Kley has pointed out in one of his most important books, the affair as a whole represented problems between different aspects of the French government, again the Parlement of Paris (a sort of law court not to be confused with a parliament) and the monarchy. Beyond that it showed the monarchy’s notion of punishment as excessive. The punishment for a failed murder went well beyond even the whole ancient “eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth” concept of justice. Thus, future revolutionary writers including Thomas Paine would cite the treatment of Damiens as an example of despotic excess from eighteenth-century monarchies.

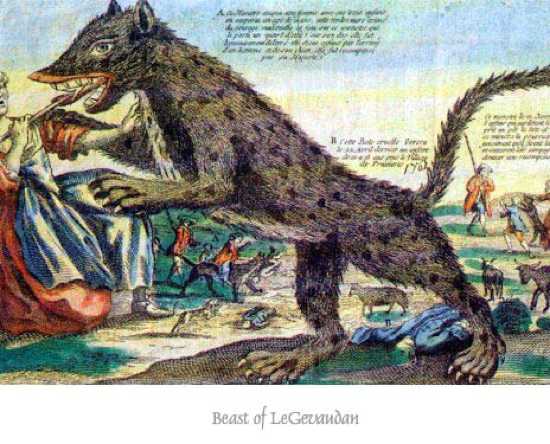

Louis XV had more to contend with during his reign than just assassination. Fans of the Atmosfear/Nightmare series may also be familiar with this entry on our list as will those of a visually stunning film called Brotherhood of the Wolf directed by Christophe Gans, who went on to direct the film version of video game Silent Hill. In the decade following the Damiens Affair, something (speculated at various points to be a serial killer, a werewolf, a regular wolf, and even a lion) killed and injured at least scores, but possibly hundreds, of French men and women in what is now the départment of Lozère. Massive effort to find the culprit was undertaken, including dozens of hunters and even soldiers with noble and royal backing to apprehend and/or kill whatever was behind the deaths plaguing the province. As the deaths continued for a few years, the apparent inability to capture or kill the beast suggested an incompetent monarchy, especially when the court celebrated the beast’s death only to have more killings continue shortly afterwards. The beast’s infamy was such that Robert Louis Stevenson described it as “the Napoleon Bonaparte of wolves.”

Speaking of Napoleon, in the year following his final defeat and the restoration of the French monarchy under Louis XVIII (yes, Louis is a popular name for French monarchs), another terrible event in French history occurred, but unlike all the other examples, this one took place outside of France proper and instead on the Atlantic Ocean. Whereas Napoleon attempted to establish a system of appointments based on merit (aside, of course, from placing his siblings on thrones), Louis XVIII returned to the monarchic practice of appointments based on familial descent or connections. An incompetent viscount captained a French frigate (the Medusa) sent with three other ships to transport the new governor of a French colony in West Africa along with other colonists. The ineptitude of the viscount’s captaining of the ship resulted in it running aground on a sandbank off the coast of what is now Mauretania.

With the ship apparently hopelessly stuck, most of the ship’s crew and passengers escaped on the lifeboats; however, more than a third of the remaining number (around 146 men and one woman) instead loaded onto a raft constructed out of parts of the Medusa in cramped and uncomfortable conditions. Initially, the lifeboats towed the raft, until eventually letting it loose, perhaps out of fear of what the increasingly annoyed people on the raft might do to those enjoying far more comfortable conditions on the lifeboats. For the next thirteen days, the raft floated in the ocean with no official attempt made to rescue the roughly 147 people on board. Finally, after nearly two weeks, another ship from the convoy, the Argus, rescued the only fifteen survivors, the other 132 persons having died of starvation, being thrown overboard, or killed in fighting over the limited supplies. Two survivors wrote an account of their struggle to survivor and renowned painter Théodore Géricault painted a haunting depiction of the survivors amidst remnants of those less fortunate shortly before their rescue. Thus, this shipwreck is an example of the mistake in appointing an untrained person to a position due to birth or title rather than actual ability. Moreover, that the captain was not more severely punished for his blundering was also appalling. All in all, the event hardly helped to endear anyone to the restored monarchy after having gone through the preceding years of revolution. It is not surprising that further discontent continued over the subsequent years that resulted in the definitive downfall of the Bourbon dynasty.

The Bourbon dynasty collapsed under the reign of Louis XVIII’s successor Charles X of France and led to a short lived continuation of the French monarchy under a man from a different line of the French royal family that also ended in a revolution. Having not learned from the mistakes of his predecessors, Charles X reigned in a manner reminiscent perhaps of James II in England over a century earlier who did not learn from what happened to Charles I of England. Charles X embraced the notion of being an absolute monarch once again. The tipping point came when he suspended the constitution after election results he deemed unfavorable. Crowds denounced this action. Charles’ government responded by sending in police forces to shut down critical newspapers, further angering Parisians. Some protesters attacked the police, who not surprisingly responded by shooting the protesters. A full-fledged riot ensued and after the Three Glorious Days, a nice name for days of bloodshed, Charles X abdicated in favor of Henry V. Instead, Louis Philippe of the Orléans branch of the royal family proclaimed himself King of the French. He reigned until 1848 when yet another French revolution occurred. Although the French monarchy has not been restored, monarchist groups still exist in France. After all these tragedies, it is unlikely France will ever see a return to absolute monarchy, but could or should a constitutional monarchy ever make a comeback in France?