Misconceptions

Misconceptions  Misconceptions

Misconceptions  Books

Books 10 Crazy Moments in the Original Sherlock Holmes Stories

Religion

Religion 10 Tales from the Lives of the Desert Fathers

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Crazy Teachers in Pop Culture

Animals

Animals From Animals to Algae: 10 Weird and Astonishing Stories

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Deadly Tiktok Challenges That Spread Like Wildfire

Humans

Humans 10 Inventors Who Were Terrible People

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Famous Brands That Survived Near Bankruptcy

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Chilling Facts about the Still-Unsolved Somerton Man Case

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Truly Wild Theories Historical People Had about Redheads

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Historical Events That Never Happened

Books

Books 10 Crazy Moments in the Original Sherlock Holmes Stories

Religion

Religion 10 Tales from the Lives of the Desert Fathers

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Crazy Teachers in Pop Culture

Animals

Animals From Animals to Algae: 10 Weird and Astonishing Stories

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Deadly Tiktok Challenges That Spread Like Wildfire

Humans

Humans 10 Inventors Who Were Terrible People

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Famous Brands That Survived Near Bankruptcy

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Chilling Facts about the Still-Unsolved Somerton Man Case

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Truly Wild Theories Historical People Had about Redheads

10 Historical Books With Far Reaching Effects

You wouldn’t know it from the way they’re treated today, but books used to be a pretty big deal in the cultural landscape. And not just your Bibles and Manifestos and Mein Kampfs, either—there are plenty of under-the-radar works that had a significant effect on something, somewhere. Sometimes lots of things, and lots of wheres. Here are ten books from back in the day that didn’t change history, but at least deserve to be noted in it.

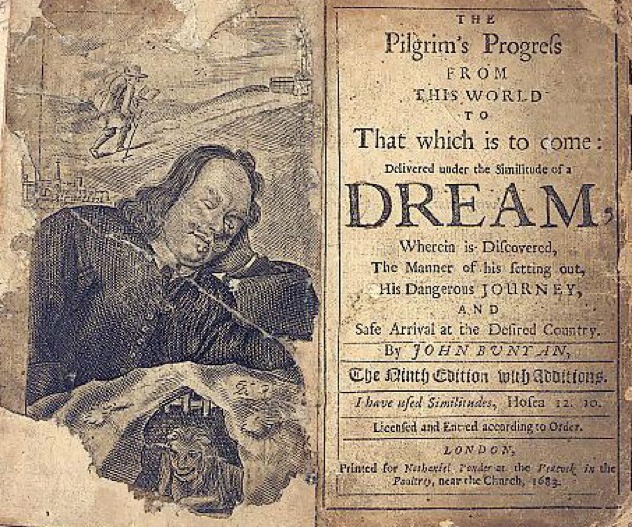

John Bunyan’s “The Pilgrim’s Progress from This World to That Which Is to Come” is the story of the subtly-named Christian, a man who leaves the City of Destruction to find the Celestial City on Mt. Zion. In other words, it’s an allegory about the religious journey from Earth to Heaven, which was the kind of thing people liked to read about in 1678, when the book was published. Interestingly, Bunyan wrote a lot of the book from prison, having spent a total of 12 years there for preaching without a license. Doing this via literature wasn’t against the law, though, and his book became an instant hit, and won him widespread fame. “The Pilgrim’s Progress” is notable for being translated into over 200 languages—more than any other book save the Bible—and being one of the most-read books in English. As for Bunyan, apparently his fellow Puritans begged to be buried next to him when they died (and not, for some reason, the actual Mt. Zion).

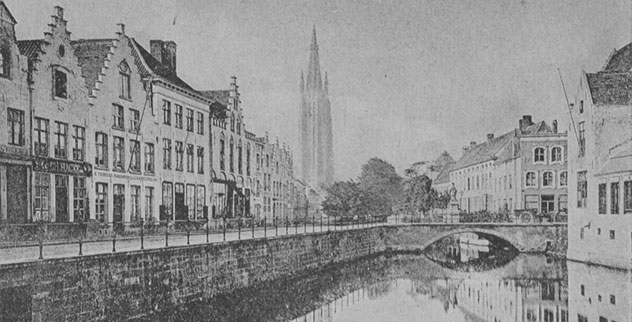

“The Dead Bruges,” as it could be called in English, is a short novel published by the writer Georges Rodenbach in 1892. It takes place in the Belgian city of Bruges, where a man named Hugues Viane moves after his wife dies. He is absolutely stricken with grief, despite his cool new city, and lives in despair for a while amidst the relics and possessions of his late love. Eventually he meets another girl, but—spoiler alert—ends up strangling her because she’s not enough like his dead wife. The book received a fair amount of success upon its release, but is most notable for a few different reasons—most importantly, “Bruges-la-morte” was the first work of fiction to ever be illustrated with photographs (mostly shots of the city). It was also quite possibly the inspiration for Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, another classic, as well as being one of the most significant Symbolist novels ever written (which basically just means that very little happened in it).

Here’s another one written in French, this time by an actual French writer (as is probably evident by his name). Pierre Louÿs’ “Les Chansons de Bilitis” is an 1894 book of erotic poems, which he claimed in the foreword were written by an Ancient Greek woman named Bilitis. This actually fooled a lot of scholars for quite a while, because the poems expertly echoed the writing of the Greek poet Sappho, of whom Louÿs claimed Bilitis was a contemporary. Of course, the poems were actually written by Louÿs himself—and, given that the name he gave the fictional discoverer of Bilitis’ poems was the equivalent of “Mr. S. Ecret,” you’d think the scholars would have realized that immediately. In any case, the collection is most significant for its acceptance of lesbians (such as Bilitis and Sappho), who weren’t treated as equally in 1894 as they are today. In fact, the book inspired the propagation of gay rights, as well as the name for the Daughters of Bilitis—the first lesbian civil and political rights group in the United States.

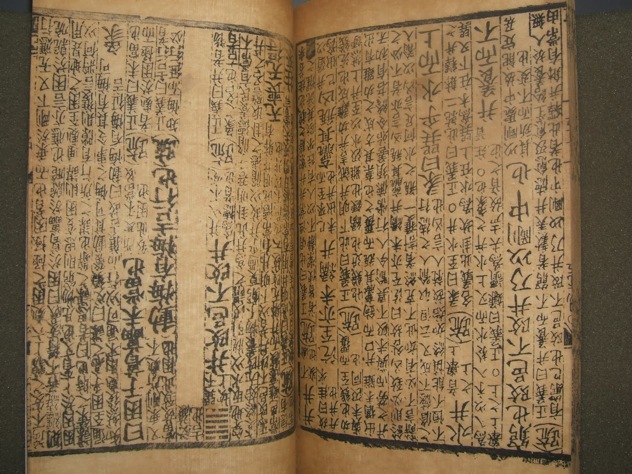

Fu Xi is said to have reigned over Ancient China during the 29th century B.C., but he was also said to have lived to 197 and made people out of clay, so take that with a grain of salt. Regardless, the “I Ching”—which Fu Xi is reputed to have written—has existed since at least 1000 B.C., making it one of the oldest classic Chinese texts in existence. The book, sometimes called the “Book of Changes,” contains oracles represented by series of binary lines called hexagrams. The idea was to somehow cast these hexagrams (by burning a turtle shell and interpreting the cracks, for example), and read the resulting interpretation in the “I Ching” so as to divine the answer to a question. Today we have Magic 8 Balls for this type of thing, but for a few thousand years it was a pretty big deal. The philosophies in the book, divination aside, have proved pretty resilient too (the lines in the hexagrams represent ‘yin’ and ‘yang’). Pictures of trigrams—half hexagrams—can still be found all over the place, from the flag of South Korea to the DHARMA Initiative.

The Bhagavad Gita, commonly referred to as simply the Gita, is an important scripture contained within the ancient, larger Hindu epic Mahabharata (‘larger’ as in ridiculously larger, as in almost two million words). The verses of the Gita, arguably the most important part of the Mahabharata, relate the philosophical and theological wisdom of Lord Krishna to the protagonist, Arjuna. This sounds a little dry in theory, but the work is notable for influencing so many significant people throughout the years, religious and non-religious types alike—people like Albert Einstein, Aldous Huxley, and Carl Jung, who all praised the work. And J. Robert Oppenheimer, who headed up the Manhattan Project during WWII, famously quoted the Gita after the first successful atomic bomb test: “Now I am become death, destroyer of worlds.” Most significantly, perhaps, was Mahatma Gandhi’s appreciation of the book—he called the Gita his “spiritual dictionary.”

But enough about philosophy and spiritual fulfillment already—let’s talk about asses. The “Metamorphoses” was published by the Latin writer Apuleius around the late 2nd century A.D., but it’s more famously known as “The Golden Ass,” which is what we’re going to call it (don’t worry, we’ll cover a different “Metamorphoses” later on in the list). It’s a humorous account of a guy named Lucius, who tries to turn himself into a bird and ends up becoming a donkey instead. He then has to go on a journey to free himself from his corporeal prison, which he accomplishes through the timeless fashion of joining a cult. The book is important for a couple of reasons—for one, it was one of the first ever picaresque novels (which chronicle the outlandish journeys of lovable misfits, like Dickens’ earlier works did), and for two, “The Golden Ass” is the only Latin novel to survive in full (so now you have no excuse not to read it).

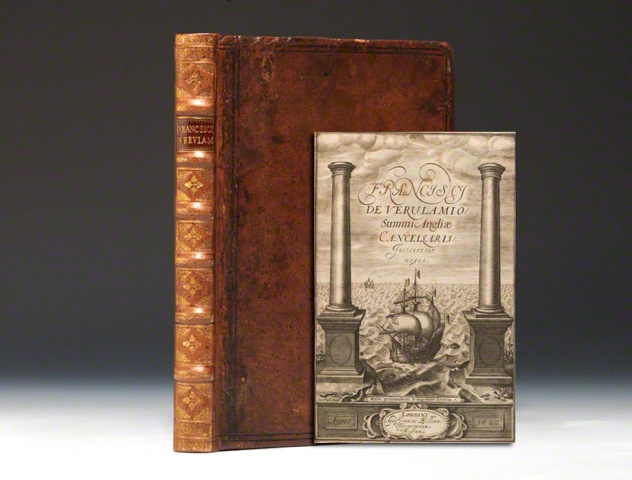

Francis Bacon is one of the most famous English philosophers (not to mention all his other jobs), and was knighted with good reason back in 1603. At the top of his list of accomplishments, perhaps, is the writing of his “Novum Organum” in 1620—in English, “New Instrument.” The book is a treatise on natural philosophy, a subject that today we generally refer to as ‘science.’ In the work, Bacon outlines a system for conducting it properly, which he believed was superior to the traditional, Aristotelian ways of doing things. The rest of the world thought so too—the Baconian method, as it came to be known, has led to Bacon being hailed the ‘father of empiricism,’ and more importantly to the kind of revolutionary ideas science has been churning out ever since. You’re familiar with the Baconian method yourself, if you’ve ever taken a science class—it’s the precursor to the modern scientific method.

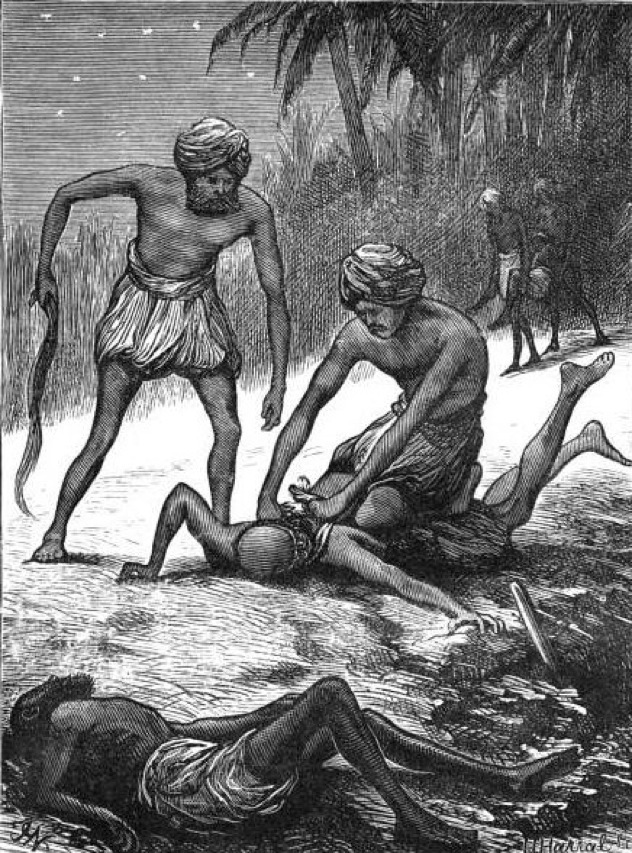

For a while there back in history—up until India gained its independence in 1947—the British decided they were in control of it. This British India was the setting of Philip Meadows Taylor’s highly influential novel, “Confessions of a Thug.” In 1839, when the book was published, the westernized idea of India was pretty remarkably racist. The British Taylor’s open-mindedness (and actual interest in realism) set new standards for the depiction of the east, and elevated the novel past being just another faraway adventure story. The protagonist, Ameer Ali, was a mass-murdering member of the very real Thuggee cult, and purportedly based on a Thug friend of the author’s. The revolutionary book went on to become a bestseller and influence the likes of Rudyard Kipling (best known for “The Jungle Book”). As the icing on the cake, the book allegedly introduced the word ‘thug’ to the English language, in much the same way that I’m about to introduce the word ‘swestering.’

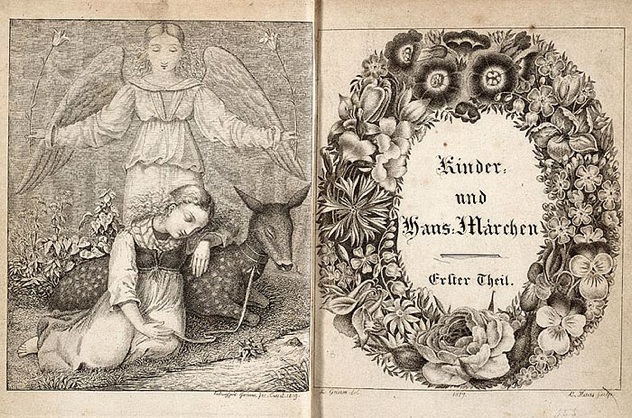

Odds are, you recognize the name Grimm (NBC certainly hopes so). Which is good—that just means it’s a good fit for the list. The first collection of Grimm’s Fairy Tales, as they’re now more commonly known, was published in 1812 under the unassuming title “Children’s and Household Tales,” in two volumes. All told, the two brothers put together over 200 German stories that were famously unsuitable for children, what with all the violence and sex and being interesting (See: Grimm, Tuesdays on NBC). Despite that, or almost certainly because of it, the collection has been pretty much a smash hit ever since—this is what rocketed the likes of Hansel and Gretel, Rapunzel, and Snow White into the cultural zeitgeist, after all (See: Once Upon a Time, Sundays on ABC. Or any Disney movie ever).

And here we have another collection of myths, this time from Ancient Rome and probably a little less well-known. The poet Ovid’s magnum opus, the “Metamorphoses,” is his own epically-presented account of over 250 myths, all of them having something to do with (you guessed it) metamorphosis. It was completed around A.D. 8, the same year Ovid was exiled from Rome for some of his other, less tasteful poetry. His myths, sharply-presented as they were, have lived on through a whole slew of famous authors—John Milton, Dante, and Geoffrey Chaucer, to name a few. Oh, and a relatively obscure guy named William Shakespeare, who not only based “Romeo & Juliet” on Ovid’s myth of “Pyramus & Thisbe,” but actually references it and others in several of his plays. In fact, it’s been claimed that the “Metamorphoses” has had more literary influence than any other work save for those of Shakespeare himself (and the Bible). Which kind of reflects poorly on the last 2000 years, actually. Come on, writers. Time to step up the game.

MJ Alba is a writer whose game is most assuredly stepped up @MattJAlba. He thinks it would be mighty swestering of you to follow him.