History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Horrific Disasters Of The Space Program

Neil Armstrong once said, “Mystery creates wonder, and wonder is the basis of man’s desire to understand.” That wonder of outer space and the unknown has driven astronauts such as Armstrong to risk their lives to explore the unknown and bring new knowledge to mankind. But for all their triumphs, the American and Russian space programs have suffered several defeats—some disastrous and some even fatal.

10X-15 Flight 3-65-97

On November 15, 1967, Michael J. Adams undocked his X-15 from the wing of its NB-52B mother ship, 13,700 meters (45,000 ft) above Delamar Dry Lake, Nevada. This was Adams’s seventh flight in the small, experimental aircraft designed for high-altitude research, and it would unfortunately turn out to be his last.

As Adams engaged full thrust, the aircraft ascended, reaching speeds above 5,000 kilometers (3,000 mi) per hour. After a few minor hiccups caused by an electrical disturbance, it reached a peak altitude of 81,000 meters (266,000 ft). As the aircraft ascended to its peak, mission control and its team of engineers instructed Adams to begin a planned wing-rocking maneuver so a fixed camera on the ship could scan the horizon.

Not long after this, the rocking became extreme, so Adams abandoned the maneuver. As the craft climbed to its maximum altitude, it was off-course by up to 15 degrees. Adams began descending at right angles to his flight path. Not suspecting anything was awry at this point, mission control told Adams that he was a little high but still in good shape.

Moments later, as the X-15 descended to 70,000 meters (230,000 ft), the aircraft entered a Mach 5 spin caused by rapidly escalating dynamic pressures. At 36,000 meters (118,000 ft), Adams recovered from the spin, but he next went into an inverted, angled Mach 4.7 dive, moving at 50,000 meters (160,000 ft) per minute. The plane faced increasing dynamic pressure and extreme forces during its sudden descent. When it hit 20,000 meters (65,000 ft), it broke up in midair. Adams didn’t survive.

Posthumously, Adams was awarded astronaut wings as his X-15 flight had passed an altitude of 80.5 kilometers (50 mi), the US definition of space.

9Soyuz 23

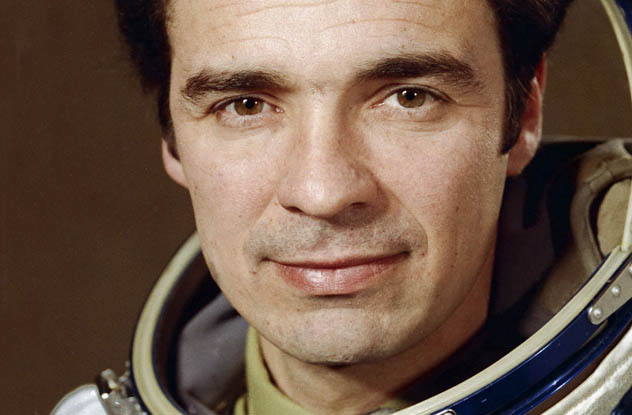

The Soyuz spacecraft were designed in the 1960s as part of the Soviet Manned Lunar Program but were eventually used to shuttle cosmonauts to and from the Salyut and Mir space stations. This particular mission of Soyuz 23 and her crew of Vyacheslav Zudov and Valery Rozhdestvensky happened on October 16, 1976 and took the craft toward space station Salyut 5.

The launch was plagued with problems from the start. First, the bus transporting the cosmonauts to the launch pad broke down. Then, at liftoff, the craft began to veer off-course due to heavy winds at the launch site. Once in orbit, Soyuz tried docking with Salyut 5, but the docking program malfunctioned and turned them away from the space station. After failed attempts to correct the error, and with fuel running low, the Soyuz turned around and prepared for reentry.

The Soyuz was supposed to land in Arkalyk, Kazakhstan, but vicious winds pushed it to an icy lake over 120 kilometers (75 mi) away. After touchdown, the parachute used to slow the craft’s descent began taking on water, dragging the spacecraft deeper and further into the lake. The cosmonauts donned all survival clothing they had available as the capsule began to freeze in the -17-degree Celsius (1.4°F) temperatures.

When morning broke, Zudov was unconscious. Frost lined the capsule’s interior. A rescue party arrived and tried to lift the module from the water, but their helicopter wasn’t strong enough, so they dragged the capsule to shore instead. Eleven hours after Soyuz 23 touched down, it finally reached safety. To the surprise of the rescue crew, both cosmonauts emerged safe and well.

8Gemini 8

In 1962, the US began the Gemini program, designed to support the Apollo lunar missions. On March 16, 1966, Gemini 8 launched successfully from Cape Canaveral, Florida, carrying Command Pilot Neil Armstrong and Pilot David Scott. The vessel aimed to perform docking tests on an unmanned target vehicle, the “Gemini Agena Target Vehicle,” or “GATV.”

They succeeded—it was the first ever successful space docking. But half an hour into the docking phase of the mission, the Gemini and Agena began to roll and yaw, forcing Armstrong to stabilize them with hand controls. The vehicles kept tumbling violently, and the astronauts disengaged from the GATV.

Once the Gemini was released, it continued an even more aggressive roll and pitch. It rotated about once every second, leaving the astronauts dizzy and at an incredible risk of blacking out.

The culprit of the increased spinning: a circuit failure to a thruster, rendering it permanently on. Once the astronauts discovered the problem, they received the order to return to Earth. The Gemini touched down safely 800 kilometers (500 mi) west of Okinawa less than 11 hours after launching.

7Apollo 1

The Apollo 1 tragedy occurred on January 27, 1967 during a simulated launch at Cape Canaveral, Florida. The crew—Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Edward H. White II, and Roger B. Chaffee—were training for a future launch by rehearsing the countdown sequence aboard a command module mounted on an unfuelled Saturn rocket.

At 1:00 PM, the three astronauts entered the module and began experiencing problems almost immediately. Grissom reported a strange sour odor inside his suit, and the countdown was held while they took an oxygen sample. Technical problems filled the next few hours—at one point, a microphone refused to turn off—but by 6:30 PM, the simulated countdown was at T minus 10 minutes.

One minute later, one of the astronauts said, “Fire, I smell fire.” Immediately after, another said, “Fire in the cockpit.” Within 17 seconds of the first report of fire, all three crew members were dead.

Carbon monoxide asphyxia had killed them all. Third-degree burns also covered all their bodies, but the asphyxiation got them first. The fire remains officially unexplained. All we know is that the oxygen-rich atmosphere, the vulnerable wiring and plumbing, and the wide allotment of combustible materials inside the cabin made for a deadly combination.

6Voskhod 2

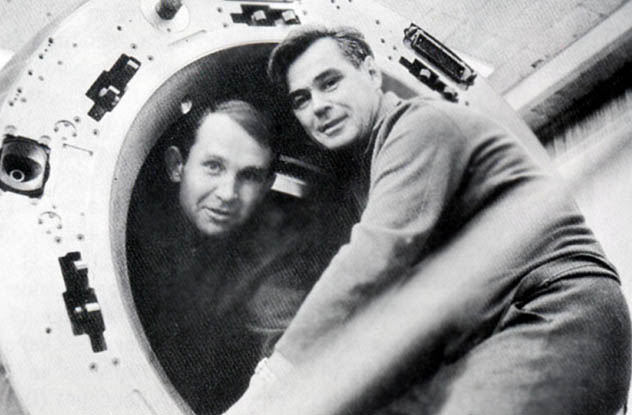

The Voskhod 2 was most memorable for being the first expedition to successfully complete an EVA (Extra Vehicular Activity), better known as a spacewalk. Like the Soyuz 23, it was also memorable for its disastrous reentry and retrieval.

On March 19, 1965, the Voskhod 2 successfully launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome, carrying Pavel Belyayev and Alexey Leonov. It began its orbit 200 kilometers (125 mi) above Earth. After Leonov completed the 12-minute spacewalk, the cosmonauts prepared for reentry. Then the automatic orientation device failed, and they had to land the craft manually, touching down in a forest far north of the intended landing site.

For four hours, the command post was unsure of Voskhod 2’s fate, until a helicopter reported a red parachute and two cosmonauts deep in the North Ural forest. The dense woodland and deep snow prevented the helicopter from landing. With no populated areas nearby, the helicopter could only fly over the cosmonauts and report back to command: “One is chopping wood, and the other is making a campfire.”

After a night in freezing temperatures, and facing the possibility of a wolf or bear attack, the cosmonauts were relieved to see a rescue team arrive on cross-country skis. They spent one more night in the forest (now with warm clothing and a tent), then headed for a small clearing where they could finally board a helicopter. They then returned to the General Secretary and reported that their mission was complete.

5Soyuz 1

Three months after the Apollo 1 tragedy, Colonel Vladimir Komarov became the first cosmonaut aboard the new Soyuz spacecraft. He faced a fate similar to those in Apollo 1. Nine minutes after takeoff on April 23, 1967, the Soyuz entered orbit and almost immediately began encountering serious problems.

During the second orbit, a solar panel that powered half the craft failed to open. By the fifth orbit, Komarov resorted to banging and kicking the side of the spacecraft to dislodge the panel. By the 13th orbit, power was critically low, so the command station decided to send up Soyuz 2 with a crew of three as a rescue mission. But an electrical storm hit the launch pad, so they abandoned that plan, leaving Soyuz 1 to fend for itself.

With things now desperate, Komarov decided to try a dangerous reentry on the 19th orbit. He wasn’t trained to reenter manually, but he managed to place the craft on its correct course. He activated his main parachute—but it deployed incorrectly. Komarov frantically deployed the backup chute, but the faulty main chute snagged it. The craft did not decelerate.

As morning broke on April 24, a number of villagers in the southern Ural Mountains witnessed a large object hurtling to the ground. Unbeknownst to them, it was Komarov, riding the Soyuz at over 140 kilometers (90 miles) per hour. He was alive and conscious right up until the point of impact.

4Soyuz 18a

Launching on April 5, 1975 and carrying cosmonauts Vasili Lazarev and Oleg Makarov, Soyuz 18a turned out to be another disaster for the Russian space program. Less than five minutes after takeoff, the cosmonauts were surprised to find the Soyuz was unexpectedly descending rapidly.

Lazarev later recalled: “We began to experience a creeping and unpleasant pull of gravity . . . It increased rapidly, and its rate was much greater than I had expected . . . Some invincible force pressed me into my seat and filled my eyelids with lead . . . Breathing was becoming increasingly more difficult.”

The spacecraft faced a peak of 21.3 G of force as the cosmonauts hurtled toward the ground. To put this into context, a Boeing 747 Jumbo jet reaches 0.35 G at takeoff. Suffering from what Makarov described as black-and-white vision and tunnel vision, the crew were dangerously close to losing consciousness completely.

Luckily, the main chutes deployed correctly. But any relief was short-lived because the craft now crashed into an unidentified icy Siberian mountain. On impact, the capsule fell to its side and immediately began sliding toward a sheer 150-meter (500 ft) drop. Playing out like a Hollywood movie, the parachute caught on some vegetation, and the craft came to stop just before the cliff’s edge.

As Lazarev put it, “The porthole, black with soot, suddenly became transparent, and I saw the trunk of a tree. Yes, this is Earth.”

3Soyuz 11

The Russian Soyuz 11 is probably best known for being the first mission to board a space station, Salyut 1. Tragically, it is also known as the first and only mission to result in human death in outer space.

After a successful launch on June 30, 1971, the crew of Georgi Dobrovolski, Viktor Patsayev, and Vladislav Volkov docked with the Salyut 1 space station for a 22-day stay. Over the next three weeks, they performed a number of scientific experiments, including measuring a human reactions to prolonged weightlessness.

Their mission done, they prepared to return to Earth. Thirty minutes before landing, the Soyuz 11 left orbit and headed for its descent trajectory. Suddenly, a critical valve blew, and pressure in the capsule dove. As their oxygen flooded out into space, the cosmonauts got hit with high-altitude decompression.

They died in less than a minute, but they did not die peacefully. Autopsies from the Burdenko Military Hospital found that within those 60 seconds, the cosmonauts experienced hemorrhages in the brain, subcutaneous bleeding, damaged eardrums, and bleeding of the middle ear. All three men would have survived—had they been provided with space suits.

2Space Shuttle Columbia

On January 16, 2003, Space Shuttle Columbia lifted off from the Kennedy Space Center carrying astronauts Rick D. Husband, William McCool, Michael P. Anderson, David M. Brown, Kalpana Chawla, Laurel B. Clark, and Ilan Ramon. After reaching orbit, the seven astronauts settled in for their 16-day stay and were kept busy by working virtually 24 hours a day. The crew conducted 80 separate scientific experiments, mainly in “SPACEHAB,” a dedicated research module nestled inside the cargo bay.

On February 1, after two weeks orbiting Earth, Columbia began its gliding descent. Only 16 minutes from Kennedy Space Center, the shuttle suddenly disintegrated. All seven astronauts died, and more than 85,000 pieces of debris blew over eastern Texas. Investigations later showed hot gases from reentry penetrated Columbia’s left wing as a result of impact with debris at launch.

1Space Shuttle Challenger

On January 28, 1986, NASA suffered its most devastating disaster. Lifting off from Kennedy Space Center, the crew of the Space Shuttle Challenger—Greg Jarvis, Christa McAuliffe, Ronald McNair, Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, Michael J. Smith, and Dick Scobee—were no doubt thrilled as they began their ascent. But only 72 seconds into the launch, mission control received its last message from Challenger. Pilot Michael J. Smith said: “Uh oh.” The shuttle then suddenly burst into flames.

As the shuttle broke up, the crew compartment continued to ascend. After 25 seconds, it reached a peak of 20,000 meters (65,000 ft) before falling. The source of the explosion was an O-ring, a mechanical gasket. The ring weakened the external fuel tank, which ultimately brought the shuttle down.

It would be a blessing to think the astronauts succumbed to the explosion instantly, but this was unlikely. A report prepared by Joseph P. Kerwin, biomedical specialist from the Johnson Space Center in Houston, said the forces during the shuttle breakup were probably insufficient to kill. In the most plausible and frightening scenario, the crew members stayed alive and conscious right up until the 333 kilometers (207 mi) per hour impact with the ocean almost three minutes after breakup.

At a memorial service held for the fallen astronauts, President Reagan summed up the disaster with simple but resonating words. “Sometimes, when we reach for the stars, we fall short. But we must pick ourselves up again and press on despite the pain.”

Ben M. is interested in history and mysteries.