Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Movies and TV

Movies and TV Top 10 Ghost Adventures Episodes That Will Haunt You Forever

Animals

Animals Ten Animals That Produce and Store Toxins in Unlikely Places

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Weird Things That Warp Your Sense of Time

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Ten More Extremely Unexpected U.S. State “Firsts”

Humans

Humans 10 Ideas That Scare People to Death

Music

Music The Cursed Decade: 10 Classic Rock Stars Who Had Low Periods in the 1980s

Health

Health 10 Crazy Ways Sleep Deprivation Can Affect You

History

History 10 Enthralling Facts about the Field of Cloth of Gold

Pop Culture

Pop Culture The Ten Greatest Engineers in Science Fiction History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Surprising Things That Were Designed to Stop Evil Behavior

Movies and TV

Movies and TV Top 10 Ghost Adventures Episodes That Will Haunt You Forever

Animals

Animals Ten Animals That Produce and Store Toxins in Unlikely Places

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Weird Things That Warp Your Sense of Time

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Ten More Extremely Unexpected U.S. State “Firsts”

Humans

Humans 10 Ideas That Scare People to Death

Music

Music The Cursed Decade: 10 Classic Rock Stars Who Had Low Periods in the 1980s

Health

Health 10 Crazy Ways Sleep Deprivation Can Affect You

History

History 10 Enthralling Facts about the Field of Cloth of Gold

Pop Culture

Pop Culture The Ten Greatest Engineers in Science Fiction History

10 Intriguing Stories Of Ordinary People In The US Civil War

Too often, we focus on the grand ideas and ideals of war instead of the stories of ordinary people who were trying to survive on the battlefields and at home. Today, we’re bringing you 10 unvarnished stories of how the Civil War affected ordinary Americans, who weren’t thinking at that time about their portrayals in history.

10Mama Told Me Not To Come

Some of the men who enlisted in the army during the Civil War were actually boys just barely into their teens. For example, in March 1862, twins John and William Moore enlisted in the Confederate Army in Richmond, Virginia, at age 16. In preparation for the Second Battle of Manassas, their regiment was ordered to join forces with the Army of Virginia. Both Maria Moore, the boys’ mother, and their family doctor sent letters to the regiment’s surgeon insisting that the twins were unfit for duty. Calling them “very sickly and delicately constituted,” the doctor wrote, “I have been the family physician of Mrs. Moore Sr. for eight years and I am convinced that they are unable to perform active service.” In October 1862, the boys were discharged because of their age, not their delicate constitutions.

Two years later, at age 18, William reenlisted. His mother couldn’t legally stop him then. He was so successful as a soldier that he was soon promoted to captain of the 15th Virginia Infantry’s I Company. William led his regiment into battle at Petersburg but was quickly taken prisoner. Three days later, on April 6, 1864, he was released after pledging his allegiance in writing to the United States of America.

The story didn’t end as happily for George Wingate Weeks. In October 1862, at age 14, he enlisted in the Union Army for a three-year tour as a drummer boy for the eighth Maine Infantry. Both he and his father had claimed George was 16 on the enlistment form. When his regiment joined the Army of the James to prepare for battle, Abigail Weeks, George’s mother, sent a letter to the chaplain of her son’s regiment asking to have George discharged because of his age. Her request was denied.

In July 1864, George was shot in the foot at Petersburg, Virginia. “We get wormy hard tack and beef that God himself would not eat if it was set before him,” he wrote to his mother. But he still wanted to serve. In October 1865, when his three years were up, George finally went home. Eventually, his wounded foot prevented him from standing and walking. Nothing more is known about George until his mother received an $8 per month pension in 1869 because 21-year-old George had died.

9Man Of The Hour

For years, Abraham Lincoln carried a secret message about the Civil War in his pocket. He just didn’t know it. He never met the man who gave it to him, either.

Despite Lincoln’s disheveled appearance, he carried the classic status symbol of the 1800s: a gold pocket watch. On April 13, 1861, Lincoln’s watch was in for repair at the M.W. Galt and Co. Jewelers in Washington, DC. Jonathan Dillon was working on it when he learned that Confederate soldiers had fired on Fort Sumter a day earlier. The Civil War had begun.

In the early 1900s, Dillon revealed to the New York Times what he had done back then to Lincoln’s watch. “I was in the act of screwing on the dial when Mr. Galt announced the news,” said Dillon. “I unscrewed the dial, and with a sharp instrument wrote on the metal beneath: ‘The first gun is fired. Slavery is dead. Thank God we have a President who at least will try.’ ”

It wasn’t until 2009 that we were able to confirm or refute Dillon’s story. Douglas Stiles, Dillon’s great-great-grandson, contacted a curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, where the watch was held, persuading him to have a jeweler open the timepiece. Photographers were there as Stiles read the engraving inside: “Jonathan Dillon April 13–1861 Fort Sumpter [sic] was attacked by the rebels on the above date J Dillon April 13–1861 Washington thank God we have a government Jonth Dillon.”

So a message was there, but it seems that Dillon remembered it incorrectly. There was also more unexpected graffiti inside the watch. Next to Dillon’s note, someone else had inscribed, “LE Grofs Sept 1864 Wash DC.” We don’t know who that is. A Confederate sympathizer may also have worked on the watch. “Jeff Davis” was etched on a brass lever.

Of course, a watch wasn’t the only receptacle for secret messages during the Civil War. According to the Museum of the Confederacy, a Virginia woman told them in 2009 that a Confederate soldier in her family had smuggled messages with a brass acorn. Although she showed the museum officials the unmarked acorn, she refused to donate it. According to stories passed down in her family, this brass rectal acorn rode in her Civil War relative’s caboose until the secret message was delivered.

8Born To Run

The 16th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry had to be one of the unluckiest Union regiments that ever existed. Less than a month after the regiment formed, they went into their first battle at Antietam on September 17, 1862. In only four hours, approximately 23,000 men from both sides died, wounded or missing in action in the bloodiest one-day battle in US history. The Union Army lost 25 percent of its men to casualties, and the Confederate Army lost 31 percent.

With no experience and having loaded their muskets for the first time one day earlier, the 16th Connecticut lost 52 percent of its men, some of them deserters, at Antietam. “Hundreds of cannon were . . . aimed at us; [grapeshot] and canister, marbles and railroad iron were showered down like rain,” wrote Lieutenant Bernard Blakeslee. “A battery was ordered up to engage the enemy, but it was whirled back in less than five minutes, losing every officer, seven men, and five horses. To see those men stand there and be shot down till they received orders to retire was a fearful sight.”

One of the deserters, 18-year-old Dixon Tucker, fled to England. The son of a well-known minister, Tucker spent the rest of his life in England, where he died in 1893, with only a visit or two back to the US. His modern British relatives believe he didn’t return to live in the US because of the shame he had caused his American family. His maternal grandfather was Nathan Fellows Dixon, the first Rhode Island senator. Other relatives were in US public service, too. Although no one is sure why he deserted, his British family does know that he preferred exile to amnesty.

Tucker worked as a clerk in a Birkenhead, England, shipyard. In 1873, he married Agnes Lawson Finley. They had nine kids. His great-grandson, Bob Ballan, of Surrey, England, didn’t even know about Tucker or his US relatives until he investigated his ancestry.

So what might have happened if Tucker had stayed with the 16th Connecticut? In 1864, almost everyone in the regiment surrendered in Plymouth, North Carolina, and was sent to the infamous Andersonville prison in Georgia, where about one-third of the men died.

7Anxiety’s Moment

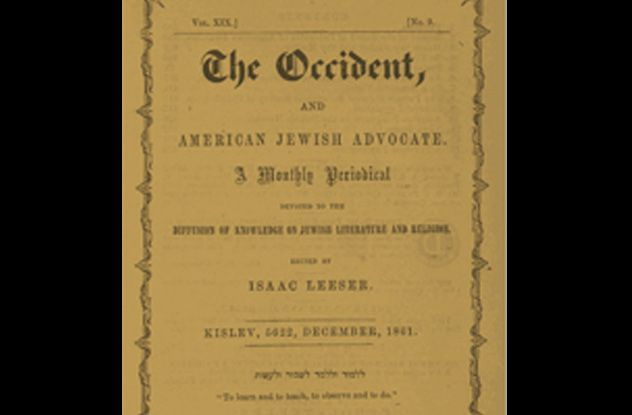

During the mid-1800s, Isaac Leeser published The Occident, a monthly newsletter that advocated the traditional approach to the Jewish religion. Although he wasn’t an ordained rabbi, Leeser assumed a similar lay position, called a Chazzan, preaching to a Philadelphia congregation.

About a month after the Civil War began, an Occident subscriber, identified only as R.A.L., wrote to Leeser with an unusual suggestion to end the war. “[Let] me beg of you to write to President Lincoln to exert your reasoning powers with him to stay this outrageous war,” said R.A.L. “If they think these difficulties cannot be settled except at the point of the bayonet, would it not be far better that a Champion be selected on each side and let victory be assigned on the side of the one who proves victorious in the contest. It certainly would be far more humane that one or two be sacrificed in our Country’s cause than that the blood of many be [uselessly] shed . . . ”

Preferring to stay neutral during the war, Leeser never took R.A.L.’s suggestion.

6That Smell

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but it can never fully convey the horrors of war. The sulfur smell of exploding gunpowder permeated war zones like a garbage dump of rotten eggs. Then there was the smell of death.

As 23-year-old Cornelia Hancock, a Gettysburg nurse, wrote to her family: “A sickening, overpowering, awful stench announced the presence of the unburied dead upon which the July sun was mercilessly shining and at every step the air grew heavier and fouler until it seemed to possess a palpable horrible density that could be seen and felt and cut with a knife . . . ”

Hancock believed that smell could kill the injured men who lay among the corpses waiting for medical teams to help them. “Not the presence of the dead bodies themselves, swollen and disfigured as they were and lying in heaps on every side, was as awful to the spectator as that deadly, nauseating atmosphere which robbed the battlefield of its glory, the survivors of their victory, and the wounded of what little chance of life was left to them,” she said.

Apparently, today’s military agrees with Hancock. The US Marines and Army train their forces with simulations that use odors like decomposing flesh and melting plastic so that soldiers won’t be distracted by overwhelming smells in the battlefield. These armed forces also teach recruits to use smell to recognize dangers. For example, the odor of cigarette smoke near a seemingly empty building may indicate the presence of the enemy.

5Can This Be Real?

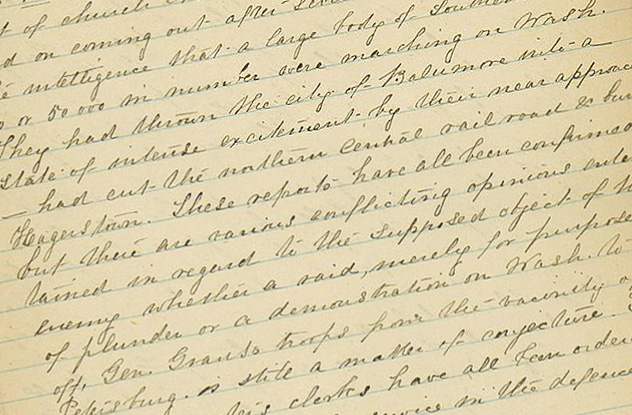

As the 30-year-old daughter of the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Mary Henry kept a careful diary of her privileged life in Washington, DC, during the Civil War. She recorded everything from troop movements to volunteering at hospitals to socializing with generals who provided eyewitness accounts of the battles.

After church services on July 10, 1864, Mary heard about the South’s advance on Washington. Although she’d been told that as many as 50,000 Confederate soldiers were on their way, it was actually about 14,000 men. Almost completely defeated, the South was taking one last run at salvaging their position. The Confederate commander, Jubal Early, wanted to capture Washington, its resources, and its president, if possible. Such a victory might throw the November 1864 presidential election to George McClellan instead of Abraham Lincoln. McClellan was willing to negotiate a settlement with the South that would allow the Confederacy to survive. Lincoln refused to do so.

Unfortunately for the South, the Confederate soldiers were just too tired to press on to Washington. Although the rebel troops came close, the city remained safe as the enemy was successfully repelled. On the afternoon of July 13, Mary went for a drive with her family to see what had happened in the surrounding areas. Her diary entries give us a good view of the dangers and devastation faced by those left at home during wartime.

In one entry, Mary recounts the story of a woman whose husband was away fighting for the Union. Confederate soldiers had pushed into her home, tearing and burning her clothes as revenge for imagined actions her husband had probably taken in the Confederate states. Then they stole her food, leaving nothing for her kids, and threatened to torch her house.

Mary and her party saw many individuals standing miserably outside of their burned homes. But the danger didn’t only come from the Confederate side. One woman told Mary that a Union soldier had asked her for kerosene oil, a wick, and cotton cloth. She quickly retrieved the items. “What do you want to do with these things?” she asked. “Burn your house, madam,” the soldier coolly replied. Although the woman tried to remove her belongings from the house, she lost almost everything in the fire.

4‘Home, Sweet Home!’

When the Civil War began, John Howard Payne had been dead for almost a decade. But during the war, he may have had the most comforting effect of any person, living or dead, on ordinary Americans.

In 1822, Payne wrote the song “Home, Sweet Home!” The climactic number to an operetta called Clari, the sentimental ballad was an instant hit that evoked the warm feeling of family in a humble home. With ineffective copyright laws, Payne earned almost nothing from the song. He wasn’t good with money anyway, so he struggled financially his entire life. Payne died in 1852.

“Home, Sweet Home!” rose in popularity again shortly after the Civil War began. Brass bands for both the Confederate and Union armies performed the song. Folk musician Tom Jolin believes that soldiers would have played this tune on their harmonicas as they sat around campfires. Many stories exist of soldiers from both sides singing together across battle lines the evening before or after they fought each other. Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln said that the ballad was the only song that could comfort them after their 12-year-old son, Willie, died.

So strong was the effect of this song that the Union Army forbade regimental bands to play “Home, Sweet Home!” because authorities thought their soldiers would become too homesick to go into battle. Years later, the song hadn’t lost its power, with members of a regiment shipping off to the Spanish-American War supposedly trying to jump overboard after jazz pioneer Buddy Bolden started playing it on the dock.

3The End Of Innocence

Originally from Vermont, 19-year-old William Hopson relocated to Macon, Georgia, in 1855 to become a cotton merchant. When Georgia seceded from the US in early 1861, William was as passionate about defending his new home state as any native Georgian. In a letter to his sister in Vermont, he called any man who deserted the Confederacy “a dastardly coward.”

William joined the Confederate Army just eight days after the war began. It was his 25th birthday. We don’t know much about his war experiences until he was wounded during the Battle of Boydton Plank Road (Burgess Mill) in Virginia when the Union Army unsuccessfully tried to seize the Southside Railroad, the only one still bringing supplies to Confederate soldiers in Petersburg, Virginia, in late 1864. Disabled, he was sent home to Georgia on furlough, where he remained until the Civil War ended in 1865.

But the war brought more unexpected tragedy to William. Edward Hopson, his younger brother who had fought for the Union Army, died during the Battle of Cedar Creek in Virginia only a few days before William was wounded. Another brother, George, eventually retrieved Edward’s body from Virginia and reburied it in Vermont.

Memories of the war became a “hideous dream” to William. As he wrote to his sister in December 1865, almost eight months after the war ended, he often saw the beauty of nature silently protesting against the vile acts of man during the war.

“We could stand grimly for months,” he wrote, “contending for some chosen position, and the tide of battle would ebb and flow over the same ground, the woods would be burned, every green thing destroyed, all scorched, blackened, desolated, until it would seem the good old world of my childhood and youth had passed forever away and in its stead a hideous chaotic ruin, whose air was tainted by the living and the dead, whose day was darkened by smoke and sulfur clouds, whose night was lit by lurid unearthly fires—a land whose chief sounds were the thousand tongued engines of destruction, the groans of wounded and the death rattles.”

In closing, he said, “A strange, wild experience—Heaven grant it may be the last.”

For William, it was. At age 37, he died suddenly in New York from inflammation of the brain and bowels.

2Heaven Must Be Missing An Angel

When 11-year-old Barbara Dosh and her siblings became orphans in 1850, the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth in Louisville, Kentucky, stepped in to care for them. Barbara loved the sisters, who performed good deeds for the local population. Although the nuns eventually sent her to St. Vincent’s Academy as a music major, Barbara combined her love of music with her love of God after graduation. As Sister Mary Lucy Dosh of the Sisters of Nazareth, she traveled in 1861 to Paducah, Kentucky, to become a music teacher at St. Mary’s Academy.

But the Civil War changed her plans. Although most of Paducah was sympathetic to the South, two Union regiments took control in September 1861. With rising numbers of soldiers contracting dysentery, malaria, and yellow fever, churches in the area were used as hospitals. Due to a shortage of nurses, Sister Mary Lucy left her teaching post to volunteer at the Paducah Baptist Church.

Soon, the 22-year-old nun energetically tended to the Union and Confederate wounded from the Battle of Belmont, Missouri. Singing quietly to her patients with her sweet voice, Sister Mary Lucy reminded them of their loved ones from home. To provide more food for the injured and sick, the young nun minimized the amount of food she ate, which weakened her. When she didn’t show up for work one day, her adoring patients became worried. What had happened to their “angel of mercy?”

Sister Mary Lucy had contracted typhoid fever during an epidemic. She died on December 29, 1861.

The soldiers were devastated. To honor her, they gave Sister Mary Lucy a military funeral at the church. Then both Union officers and Confederate officers, who were also prisoners of war, carried her coffin to the gunboat Peacock. The boat went to Union County, Kentucky, under a flag of truce between the two sides. Sister Mary Lucy was buried in the cemetery at St. Vincent’s Academy in Union County.

Afterward, the soldiers gave one last tribute to the young nun. The Northern officers released the Southern officers, each returning to their respective side of the war. For that one day, the war was halted in part of Kentucky to honor the selfless sacrifice of a young nun.

1The Gambler

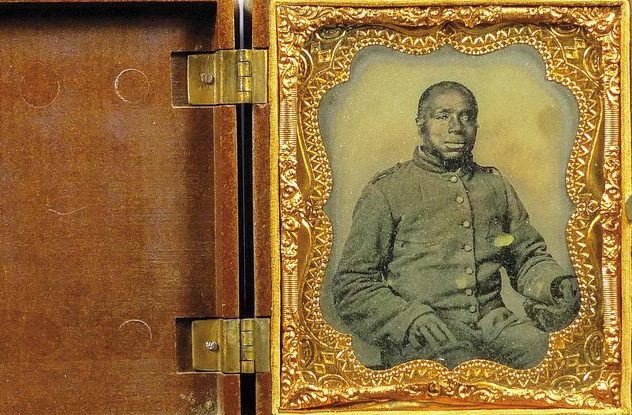

Robert Webster was one of the richest men in Atlanta during the Civil War while he was a slave. When his master, Benjamin Yancey, lost all his money after the war, Webster loaned Yancey enough to reestablish his credit and his business with the promise of more money if Yancey needed it.

Born a slave at the National Hotel in Washington, DC, in 1820, Robert Webster always claimed his father was Massachusetts senator Daniel Webster. Nevertheless, Robert Webster was sold in his twenties to a plantation owner in South Carolina. While there, Webster met Benjamin Yancey, a wealthy lawyer and planter who was soon taken with the slave’s intelligence, honesty, and affection.

Eventually, Webster convinced Yancey to buy him and his wife. When Yancey was later sent to Argentina as a diplomat, he gave his slave a barbershop in Atlanta in exchange for rent each month. Webster quickly expanded to two shops with a staff of seven. But he made his real money as a loan shark to gamblers in the constant card games he held at one of his barbershops.

When Yancey came back from Argentina, he also settled in Atlanta, which soon became a chaotic boomtown during the Civil War. Webster saw the constant flow of refugees and soldiers as an opportunity to make money speculating in gold and currency. Then he used that money to buy goods that he could trade for even greater profit.

At times, he also helped Union soldiers escape at great risk to himself. His most daring act was to organize other slaves to transport hundreds of severely injured Union soldiers from an Atlanta field to a hospital, where their lives were saved. However, when Atlanta surrendered to the Union, their troops raided Webster’s stash of goods for supplies to support Union forces. They took a lot, but not everything, from shrewd Webster, who successfully hid some of his money.

After the war, Webster was initially successful, but he later succumbed to drinking. When his businesses failed, he reached out to Yancey for help in 1880. Still grateful for how Webster had bankrolled him right after the war ended, Yancey took care of Webster and his family from then on. Even after Webster died in 1883, Yancey provided for his widow and daughter.