Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Top 10 Bizarre Cases of Mass Hysteria

Mass hysteria is the common term used to describe a situation in which various people all suffer from similar hysterical symptoms – either from a phantom illness or an inexplicable event. This list looks at ten of the most well known cases of Mass Hysteria – from the past and present.

The 2006 Mumbai “sweet” seawater incident was a phenomenon during which residents of Mumbai claimed that the water at Mahim Creek, one of the most polluted creeks in India that receives thousands of tonnes of raw sewage and industrial waste every day, had suddenly turned “sweet”. Within hours, residents of Gujarat claimed that seawater at Teethal beach had turned sweet as well. In the aftermath of the incidents, local authorities feared the possibility of a severe outbreak of water-borne diseases, such as gastroenteritis. The Maharashtra Pollution Control Board had warned people not to drink the water, but despite this many people had collected it in bottles, even as plastic and rubbish had drifted by on the current. By 2pm the following day, the devotees said that the water was salty again.

The Tanganyika laughter epidemic of 1962 was an outbreak of mass hysteria, believed to have occurred in or near the village of Kashasha on the western coast of Lake Victoria in the modern nation of Tanzania near the border of Kenya. It is possible that, at the start of the incident, a joke was told in a boarding school, and that this joke triggered a small group of students to start laughing. The laughter perpetuated itself, far transcending its original cause. The school from which the epidemic sprang was shut down; the children and parents transmitted it to the surrounding area. Other schools, Kashasha itself, and another village, comprising thousands of people, were all affected to some degree. Six to eighteen months after it started, the phenomenon died off. The following symptoms were reported on an equally massive scale as the reports of the laughter itself: pain, fainting, respiratory problems, rashes, and attacks of crying.

The Hindu milk miracle was a phenomenon considered by many Hindus as a miracle which occurred on September 21, 1995. Before dawn, a Hindu worshiper at a temple in south New Delhi made an offering of milk to a statue of Lord Ganesha. When a spoonful of milk from the bowl was held up to the trunk of the statue, the liquid was seen to disappear, apparently taken in by the idol. Word of the event spread quickly, and by mid-morning it was found that statues of the entire Hindu pantheon in temples all over North India were taking in milk. A small number of temples outside of India reported the effect continuing for several more days, but no further reports were made after the beginning of October. Skeptics hold the incident to be an example of mass hysteria, and when reports of the Monkey-man of New Delhi (item 3) began to appear in 2001, many newspapers harked back to the event.

In 1962 a mysterious disease broke out in a dressmaking department of a US textile factory. The symptoms included numbness, nausea, dizziness, and vomiting. Word of a bug in the factory that would bite its victims and develop the above symptoms quickly spread. Soon sixty two employees developed this mysterious illness, some of whom were hospitalized. The news media reported on the case. After research by company physicians and experts from the US Public Health Service Communicable Disease Center, it was concluded that the case was one of mass hysteria. While the researchers believed some workers were bitten by the bug, anxiety was likely the cause of the symptoms. No evidence was ever found for a bug which could cause the above flu-like symptoms, nor did all workers demonstrate bites.

Morangos com Açúcar is a Portuguese youth soap opera, which is very popular in Portuguese communities, especially amongst children and teenagers, aiming to depict the adventures of typical Portuguese youths. In May, 2006, an outbreak of the “Morangos com Açúcar Virus” was reported in Portuguese schools. 300 or more students at 14 schools reported similar symptoms to those experienced by the characters in a recent episode. These included rashes, difficulty breathing, and dizziness, forcing some schools to close. The Portuguese National Institute for Medical Emergency dismissed the illness as mass hysteria. This story concerned some parents because of the major influence this series has on the kids and teens that watch, it was in newspaper and magazines articles and elsewhere.

Gloria Ramirez was a Riverside, California, woman dubbed “the toxic lady” by the media after exposure to her body and blood had sickened several hospital workers. She was rushed to hospital in 1994 suffering from the effects of cervical cancer. The medical staff who attended to her all began to feel ill and eventually fainted. Gloria’s body exuded a garlicky and fruity smell and her blood contained flecks of a strange substance like paper. The odd thing about this case is that of those who handled Gloria’s body or treated her, more women than men suffered from the ill-effects and everyone involved had normal results in blood tests. The health department issued a statement at the conclusion of their investigation which said that those who had become sick were, in fact, suffering from mass hysteria.

The War of the Worlds was an episode of the American radio drama anthology series Mercury Theatre on the Air. It was performed as a Halloween episode of the series on October 30, 1938 and aired over the Columbia Broadcasting System radio network. Directed and narrated by Orson Welles, the episode was an adaptation of H. G. Wells’ novel The War of the Worlds. Some listeners heard only a portion of the broadcast, and in the atmosphere of tension and anxiety leading to World War II, took it to be a news broadcast. Newspapers reported that panic ensued, people fleeing the area, others thinking they could smell poison gas or could see flashes of lightning in the distance. Some people called CBS, newspapers or the police in confusion over the realism of the news bulletins. Initially Grover’s Mill (the site of one of reports in the drama) was deserted, but crowds developed. Eventually police were sent to control the crowds. To people arriving later in the evening, the scene really did look like the events being narrated, with panicked crowds and flashing police lights streaming across the masses. There were instances of panic throughout the US as a result of the broadcast, especially in New York and New Jersey.

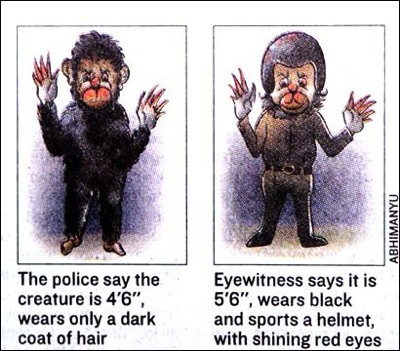

In May 2001, reports began to circulate in the Indian capital New Delhi of a strange monkey-like creature that was appearing at night and attacking people. Eyewitness accounts were often inconsistent, but tended to describe the creature as about four feet (120 cm) tall, covered in thick black hair, with a metal helmet, metal claws, glowing red eyes and three buttons on its chest. Theories on the nature of the Monkey Man ranged from an avatar of a Hindu god, to an Indian version of Bigfoot, to a cyborg that could be deactivated by throwing water on the motherboard concealed under fur on its chest. Many people reported being scratched, and two (by some reports, three) people even died when they leapt from the tops of buildings or fell down stairwells in a panic caused by what they thought was the attacker. More than 15 people suffered from bruises, bites, and scratches.

A penis panic is a mass hysteria event or panic in which male members of a population suddenly experience the belief that their genitals are getting smaller or disappearing entirely. Penis panics have occurred around the world, most notably in Africa and Asia. Local beliefs in many instances assert that such physical changes are often fatal. In cases where the fear of the penis being retracted is secondary to other conditions, psychological diagnosis and treatments are under development. It is becoming increasingly clear that these forms of mass hysteria are more common than previously thought. Injuries have occurred when stricken men have resorted to apparatus such as needles, hooks, fishing line, and shoe strings, to prevent the disappearance of their penises. An epidemic struck Singapore in 1967, resulting in thousands of reported cases. Government and medical officials alleviated the outbreak only by a massive campaign to reassure men of the anatomical impossibility of retraction together with a media blackout on the spread of the condition.

The Dancing Plague of 1518 was a case of dancing mania that occurred in Strasbourg, France (then part of the Holy Roman Empire) in July 1518. Numerous people took to dancing for days without rest. The outbreak began in July 1518, when a woman, Frau Troffea, began to dance fervently in a street in Strasbourg. This lasted somewhere between four to six days. Within a week, 34 others had joined, and within a month, there were around 400 dancers. Most of these people eventually died from heart attack, stroke, or exhaustion. Historical documents, including “physician notes, cathedral sermons, local and regional chronicles, and even notes issued by the Strasbourg city council” are clear that the victims danced. It is not known why these people danced to their deaths, nor is it clear that they were dancing willfully. You can read a much more indepth article on the dancing plague here.

This article is licensed under the GFDL because it contains quotations from Wikipedia.

Contributor: JFrater

![11 Lesser-Known Facts About Mass Murderer Jim Jones [Disturbing Content] 11 Lesser-Known Facts About Mass Murderer Jim Jones [Disturbing Content]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/jonestown2-copy-150x150.jpg)