History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Bizarre English Common Law Cases That Are Totally Significant

The modern English legal system didn’t just appear in its current form overnight. English case law has developed over centuries into the complex and intricate body of laws that we find today, to the extent that it can be very difficult to follow.

Over the years, certain legal disputes have become known as landmark cases, as they presented the courts with a dilemma in which a definitive decision was needed. Many of these cases had totally unique and interesting facts, and this is the focus of our list today. Read on for ten of the most bizarre—but hugely significant—common law cases in English history.

10 Donoghue v Stevenson

Any legal student or budding lawyer would be able to tell you about Donoghue v Stevenson. The decision in this famous dispute founded the general duty of care that manufacturers have to consumers. The facts of the case gave it the nickname of the “Paisley snail.” In 1928, Mrs. Donoghue purchased a bottle of ginger beer in a cafe in Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland, to pour over her ice cream (a Scottish ice cream float). She would consume some of the float. When the contents of the bottle were fully emptied into the float, a decomposed snail came out.

Mrs. Donoghue claimed illness from the snail and would also complain of stomach pains, requiring some medical attention. She was later diagnosed with severe gastroenteritis. Mrs. Donoghue took legal action against the original manufacturer of the ginger beer, and after deliberation which ended up in the House of Lords, she won against the manufacturer. Lord Atkin famously said when deliberating the case, “The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law, you must not injure your neighbour.”[1]

9 R v Collins

R v Collins is a lesser-known case with facts that sound like something out of a horror movie. The case was key in the development of English criminal law on burglary and what it means to “enter as a trespasser.” In the early 1970s in Colchester, an 18-year-old woman had gone to bed intoxicated after spending the evening drinking with her boyfriend. As her bed was near an open window, she awoke in the middle of the night to the sight of a naked male crouched at the window sill. Unbeknownst to her, he had previously been using a ladder to peep in at the woman, who was nude herself, while she slept. The woman mistook this interloping voyeur for her boyfriend.

After inviting the man into her bed and having sex with him, the woman realized the man was not her boyfriend (though it was someone she knew). After turning on the light and hitting the man, she hid in the bathroom until he disappeared, presumably back out the window. The trial examined whether the man had been “invited” by the woman or if he was entering as a trespasser. The Court of Appeal found that the male had not entered the room prior to being invited by the woman and therefore had not committed a crime by doing so.[2]

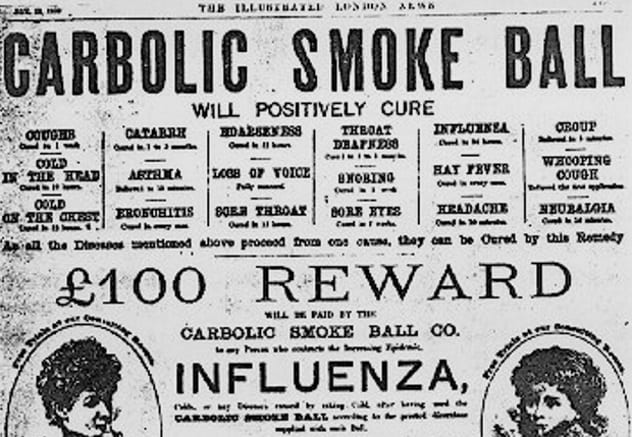

8 Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co

The landmark case of Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co is another one that all lawyers will be able to attest to knowing about. It is often first taught when describing how English contract law has been shaped by the courts. The case involved the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company, which had developed a smoke ball filled with carbolic acid to help treat the millions of sufferers of flu in England during the late 19th century. The smoke ball would make the patient’s nose run and, in theory, would flush out any viral infections. The mistake the company made was to advertise their new product with a £100 cash back offer in the event that any person who had used the device properly for two weeks still became sick with flu.

Mrs. Carlill had purchased the smoke ball based on this advertisement and used it for two months between 1891 and 1892—however, she would then contract the flu. After trying to claim her £100, she was ignored, delayed, and asked to prove her use by the company in a stalling tactic. In court, the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company argued that the offer was not serious. However, Mrs. Carlill had purchased on the premise of the offer. The judgement concluded that the advertisement was a legally binding offer to people who chose to act upon its terms and that successfully meeting those terms meant acceptance of the offer.[3]

7 R v Dudley And Stephens

The “cannibal” case of R v Dudley and Stephens is really the stuff of nightmares. The case is actually one of the leading in English criminal law which established the fact that “necessity” cannot be used as a defense when charged with murder. In 1884, a crew of four seamen were traveling from the UK to Australia to deliver the yacht they were sailing. However, in the middle of the voyage, their ship sank due to bad weather, and the seamen were left in a lifeboat. With only a few cans of turnips to eat, the men quickly ran out of food and had no fluid source. They even began drinking their own urine.

After more than ten days of this, the crew discussed drawing lots to choose a sacrificial person to kill and devour to survive. As the youngest member of the crew, Richard Parker, had become so ill they believed he was close to death, crew members Edwin Stephens and Tom Dudley ultimately killed Parker by inserting a knife into his jugular vein. The three remaining men then ate Parker to survive. In the subsequent trial, after the survivors were rescued, it was found that the necessary evil of murder was not enough of a defense for Dudley and Stephens, as this could be a “legal cloak for unbridled passion and atrocious crime.”[4]

6 R v Lipman

R v Lipman examined and established whether the fact that a person had voluntarily become intoxicated beforehand could be used as a defense to manslaughter under English criminal law. The case is considered landmark for forcing the courts to deal with the issue of unintentional murder under the influence of drugs or alcohol. The case involved a couple who regularly used recreational drugs. One evening in 1967, they both took LSD.

During the high, the man hallucinated that he was being attacked by snakes, and in the midst of defending himself from this attack, he strangled his partner.[5] He also struck multiple blows to her head. The police had found evidence that the woman had been strangled, and the man claimed he had no intention of ever doing so. The man was eventually found guilty of manslaughter despite being intoxicated, as the courts found that by creating a dangerous and reckless situation, the man had created a risk that “ordinary sober and responsible people would recognise.”

5 Scott v Shepherd

The case of Scott v Shepherd, also known as the “famous squib case,” helped establish the principle of novus actus interveniens (“new act intervening”) in the civil courts. The defendant, Shepherd, had thrown a lit squib into a crowded market place in Somerset. A squib is a small explosive device that is sometimes used for pyrotechnic effects or for generating explosive force. The squib landed on the table of a market stall, where it was subsequently thrown by a passerby into the goods of another market stall. The man who owned the second market stall picked up the squib to throw it away, but it hit another man, Scott, in the face. The squib exploded at this point and cost Scott one of his eyes.

The courts looked to establish whether the damage to Scott’s eye was caused by the actions of the original thrower (Shepherd) or one of the subsequent people who had thrown the squib. The courts found Shepherd liable for the damages, as he had placed all of the subsequent people into a spiral of action “under a compulsive necessity for their own safety and self-preservation.”[6]

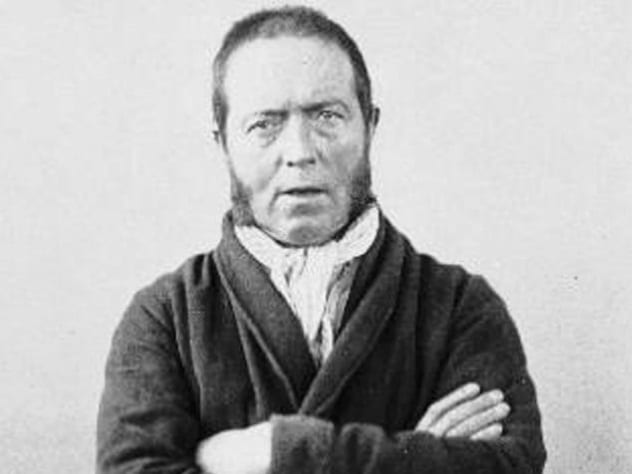

4 R v M’Naghten

The high-profile case of M’Naghten from the 19th century firmly introduced the rules for determining if someone can plead insanity when they have committed a crime. The rules, known as the M’Naghten rules, were created by the House of Lords during the case and establish if someone is acting under a “disease of the mind” in a criminal case. The facts of the case were also high-profile, as they involved then-Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel.

The defendant, Daniel M’Naghten (pictured above), attempted to assassinate the prime minister in 1843 after mysteriously stalking him for a time. On the afternoon of January 20, M’Naghten followed Peel’s private secretary Edward Drummond in London and promptly shot him in the back with a pistol. M’Naghten had genuinely thought he was shooting the prime minister. Drummond would die five days later. M’Nagthen was acquitted of the murder by a jury based on a medical assessment of his mental state, which concluded that he was insane and not acting within his normal mind.[7]

3 R v White

The criminal case of R v White was important in the establishment of causation and how to determine if an act has caused the criminal action to take place. The case established the “but for” test, which asks the question, “But for the actions of the defendant, would the result have occurred?” This is an important test when determining liability of the defendant, particularly in murder or manslaughter cases.

The case in question involved attempted matricide, as a son had poisoned his mother’s milk with clear motivation to murder her. The mother drank some of the milk, but during the night, she died from an unrelated heart attack, in what was a freak coincidence. The question for the courts was whether the defendant was guilty of murder even though is actions had not actually caused the death. It was ruled that the son was guilty of attempted murder but not the more egregious crime of murder, as even if he had not acted, his mother would have died.[8]

2 R v Abdul Hussain

The case of R v Abdul Hussain involved multiple countries but was ultimately played out in the courts of England. The case established a wider scope of the defense of duress and the immediacy of a threat to the person who has committed a crime. In certain situations, duress can be claimed as a defense to a crime when someone has been placed under immediate peril of injury or death. This case looked at what “immediate” actually meant.

A family of Shi’ite Muslims from Iraq were sentenced to death after being tortured for confessions. They were living in Sudan and were in constant fear of deportation to Iraq to face their sentences. Under this duress, they hijacked and flew a plane to Stansted Airport in England to seek asylum and safety from execution. The family were convicted of hijacking but later appealed on the grounds of duress and were successful. This is because the threat of death by execution was immediate enough for the family to warrant their actions. This means the defense of duress is available to someone hijacking a plane in a bid to escape serious harm or death.[9]

1 Haughton v Smith

The case of Haughton v Smith reads like a classic tale of cops and robbers. The case established that a person cannot be convicted of possessing stolen goods or attempting to if the goods aren’t actually stolen. In this instance, police had stopped a van on the motorway which they discovered contained stolen goods. The police, in an effort to catch the accomplices who were waiting to receive the stolen goods, allowed the van to continue to the next service station. One of the waiting men, Roger Smith, was convicted of attempting to handle stolen goods.

The police’s ploy had worked, and they had caught the accomplice. However, the House of Lords overturned this decision, as they concluded that the goods were no longer “stolen” once they had been recovered by the police. It was impossible for the man to be convicted of stealing goods that were not stolen.[10] This ruling would later be overturned by the Criminal Attempts Act 1981, which created laws concerning the attempt of crime.

N/A

Read about more precedent-setting legal cases on 10 Bizarre Historical Court Cases That Were Actually Important and 10 Strange Supreme Court Cases With Lasting Impacts.