History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

Top 10 Biggest Travesties of the Oscars

Every year the Oscars come and go. Almost every year there is at least one or two controversial picks. This list looks at ten of the worst travesties relating to the Academy Awards. Undoubtedly, some will disagree with a number of the entries and will want to add their own – feel free to do so in the comments.

The Travesty: The Long, Expensive Campaigns for Nominations

It has long since become atrociously farcical how much lobbying goes into each nomination. The biggest campaigns always revolved around Best Picture, Director and the acting categories. And in order to keep a name in the Academy’s flowing cup freshly remember’d (Henry V, thank you), the respective producers lobby, lobby, lobby and shell out inordinate sums of money to get some attention. But, what about the small-budget work? The Independent films are more and more frequently snubbed in various categories these days, because they don’t have the funds to keep up with the blockbuster campaigns.

The Oscar season once lasted from about December to February, but now, a campaign better begin in summer if it hopes to hold its ground and sway opinion. Welcome to politics. Money wins.

The Travesty: Michael Moore Wins Best Documentary (2003)

Moore should have won Best Documentary for Sicko (2008). He probably didn’t win because of the moronic scene he made in 2003 when he won for Bowling for Columbine. He told everyone he would slam President Bush, but no one believed him. Right or wrong, the Oscars was not the place for it. It was similar to the (in)famous Black Panther salute of the 1968 Olympic Games. Moore was soundly booed out of the building, and Steve Martin saved the day with a great joke.

Regardless, Bowling for Columbine is not a documentary. It tells one side of the story, the liberal side, and should never have even been nominated. It was, and it won, because it was by far the most popular blockbuster of documentaries in recent history. It held its own with The Lord of the Rings: The Towers at the box office. Why? Because it’s deliberately inflammatory. The proper political argument has always been one that considers all sides (the U. S. has two, Conservative and Liberal). Moore’s film only enunciates the liberal side. It does not, therefore, properly document anything.

The Travesty: Forrest Gump Wins Best Picture (1995)

Forrest Gump was the feel-good movie of 1994. It’s got “heartwarming” moments by the bucketload. And it must have caught the Academy in a heartwarming mood, because it distracted them from its lack of a plot. It’s a series of happy, sad, humorous and endearing vignettes about the life of a mentally handicapped man, who somehow manages to be present at every single pop-culture event of the latter half of the 20th Century. That stretches the suspension of disbelief past the breaking point. The Best Picture of 1994 should have been a close race between Pulp Fiction (which does have a plot, albeit out of order) and Quiz Show.

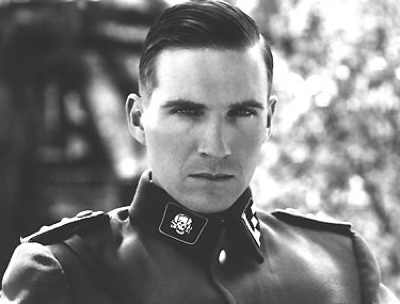

The Travesty: Ralph Fiennes Loses Best Supporting Actor (1994)

Some of the Academy’s voting panel have recently admitted that they should have voted for Fiennes’s horrific, odious portrayal of Amon Goeth. Once again (see entry #1), the Academy made the mistake of rewarding someone for a long, distinguished body of work, instead of giving the award to the year’s best performance. Tommy Lee Jones, who won for The Fugitive, is certainly superb as Deputy U. S. Marshal Samuel Gerard, but Fiennes is superlative in a performance that goes against his own nature as a human being. He succeeds in acting as if he does not understand why anyone would care about Jews. He is walking death in this film.

The Travesty: The Ten Commandments Loses Best Picture (1957)

One of the worst films ever to win Best Picture somehow managed to steal it from one of the best never to win it. The Ten Commandments does what no one thought possible at the time (even now, it’s regarded with a sense of awe since DeMille had no computers). It won the Oscar for special effects, but that’s all, and it lost Best Picture to Around the World in 80 Days. In terms of storyline, it’s usually a good bet to wager on the Bible. It has a lot of good stories, whether or not you believe them.

The story of the Exodus may be the most epic, and that’s saying a lot coming from the Bible. DeMille et al. pulled it off with awesome verve and pacing. The film is not overlong at 3 hours 40 minutes, because it persistently holds the audience enraptured with its scale and photography. People put their hands over their mouths in theaters across the country when the Red Sea parted. Right up to the last moment, they thought they would have to be cheated out of seeing it.

The Travesty: Saving Private Ryan Loses Best Picture (1999)

It lost to Shakespeare in Love, which is a great film in all respects. The final production of Romeo and Juliet, in the Globe Theater, is the best inkling on film of what it might have been like to see a Shakespeare play in Shakespeare’s day. But face it, no film has revolutionized its genre as vehemently, as fearlessly, as Saving Private Ryan for the war film. It was not until 1998 that a director managed to overpower the censors in order to show combat for what it is. This is, in terms of realism, the first war film to tell the truth. All the other great war films lied, inasmuch as they shielded the audience’s eyes to the reality of a 7.92mm bullet going through some poor, nameless private’s abdomen from the side: guts everywhere and the poor guy’s screaming for his mama.

This film takes the uninitiated audience closer to combat reality than any other, and in its wake, we now have a slew of honest war films like Black Hawk Down, Pearl Harbor, The Thin Red Line, The Hurt Locker, to name a few. We even have a still-popular WWII first-person shooter video game genre because of this film. Saving Private Ryan was the first to get it right, and it certainly set the bar high, with a perfect, simple storyline, set against an epic historical backdrop. Even Rambo IV took a new lead from it, showing Rambo’s carnage the way it always should have been.

It’s not fair to say that times had changed by 1998, and the MPAA had become more liberal. They still considered rating it NC-17 (which used to be X). This would have been the first time in history that a film were given such a rating for any reason other than sex. Spielberg finally changed their minds by tracking them down to a conference room and explaining that the MPAA had been lying to the world for 100 years, and the time of Victorian sensibilities had long since passed. Now was the time to tell the truth about Omaha Beach.

The Travesty: The Many Nominations of Peter O’Toole

Talk about the luck of the Irish. O’Toole is probably the finest actor alive today (and this lister is a huge fan of Daniel Day-Lewis). He holds the record for most acting nominations without a win, eight, all in the lead category. Granted, that category is a horse race every year, and he went up against some of the truly indelible performances, from the 1960s to the present. Gregory Peck deserved the win for To Kill a Mockingbird, but what about Rex Harrison in My Fair Lady? It’s a musical and he can’t manage more than a 4-note range in his singing voice. As a result, he did sprechenstimme, as the Germans would call it, “singing speech.” His acting is just fine, but there’s something glaringly absent in the film without the main character singing his songs.

Then the Academy shamed itself in 1969, when it gave the award to Cliff Robertson, an American, instead of O’Toole, from the U. K. O’Toole put forth the performance of a lifetime as King Henry II, the second time, after Becket, and the result was poetry in motion and speech. It sounds like Shakespeare, but it comes out like common conversation. It may be his best work. But then there’s Venus (2007), in which he plays a fictitious old man who’s obsessed with a 16-year-old girl. The award went to Forest Whitaker as Idi Amin, a real person. When it comes to acting, the fictitious characters have always been much more difficult to portray than real people. Whitaker had the real Amin’s performances in newsreels to impersonate. O’Toole had no one but himself.

The Academy should have done one of two things that year: either not nominated him at all, or given him the win. This lister believes that of the 5 nominated performances, O’Toole’s is truly the best. It was consummate understatement throughout, instead of the flashy bravura Whitaker put forth. Bravura routinely wins.

The Travesty: Stanley Kubrick Never Won Best Director

Like the next entry, Kubrick directed some of cinema’s absolute masterpieces, films that have stood the test of time and remain utter genius in all regards. He was nominated for 4 of them, and never won. He won an Oscar for his help with the adapted screenplay of Full Metal Jacket, but as a director, four of his finest efforts were evidently misunderstood. That is the certainly the case for 2001: A Space Odyssey. Some critics slammed it as incomprehensible. Others heralded it as the awakening of modern cinema. For whatever reason, it somehow managed to lose Best Director to Carol Reed, for the musical Oliver! That film is a fine work of drama, and perhaps deserved the Best Picture award. But as a director, Reed did nothing new. It’s still a musical, a good one, but nothing groundbreaking or innovative in any way (except that Oliver Twist does not have such a happy ending). Kubrick, however, landed all the technical aspects of a film with the same excellence in 2001, and also opened a multitude of new doors into science fiction drama, and filmmaking in general.

Then there’s Dr. Strangelove, easily one of the finest comedies in film history, because Kubrick had the nerve to poke fun at nuclear holocaust at the same time as the Cuban Missile Crisis. And that doesn’t mention just how sidesplittingly funny every single scene is. His idea for the war room was a giant, green roundtable, so it would be like the generals and politicians were playing poker with the world’s fate. He came up with the line, “Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here! This is the war room!” Then, consider that every performance is pitch-perfect, every scene is honed down to a razor’s edge of timing and appearance.

He should have been nominated for his directing of Paths of Glory, and perhaps Spartacus.

The Travesty: Alfred Hitchcock Never Won Best Director

Hitchcock is a byword, now, for suspense. He was nominated as director 5 times, for Rebecca, Lifeboat, Spellbound, Rear Window and Psycho. He lost all five, and was not even nominated for the now-renowned classics Vertigo, North by Northwest and The Birds. The Academy finally honored him with the Irving Thalberg lifetime achievement award, for which he walked on stage, said, “Thank you,” and walked off.

As a result of this and other oversights, the lifetime achievement awards, like the Irving Thalberg and the Jean Hersholt, have become thought of as apologies to great actors, directors, etc, who deserved a competitive win or two and never got one. Psycho, as one example, deserved the win for director over the other four nominees (look them up), because after viewing all 5 performances, Hitchcock’s is the only standout in terms of gutsiness and innovation. The main character dies 30 minutes into the film! And what a death scene! In age of ridiculous gore, Psycho still scares and shocks.

The Travesty: John Wayne Wins Best Actor (1970)

In the annals of acting awards, no honor has been so universally denounced, scorned, mocked or ridiculed as John Wayne’s lead win for his performance as Rooster Cogburn in True Grit. His portrayal has been called “hammy,” “over the top” and “mischaracterized,” among others, because he very obviously, even obscenely, comes out of character several times in the film, ceasing to be Rooster, and reverting to John Wayne. He shotguns his dialogue for a change, instead of…pausing every few words in a real…laconic delivery of his words! (his exclamation point). But his shotgun delivery tramples all over many of the other actors’ cue lines immediately before his.

He is trying his best to pull off a Spencer Tracy or a Laurence Olivier, and he fails miserably. In his defense, however, he put forth some outstanding performances in his career, in Sands of Iwo Jima and The Shootist, to name two. The Academy decided, and even admitted afterward, that it was time to honor his career with an Oscar. Thus the award went to his body of work, not his performance, whereas the other five nominated performances were all much better for that year. Any one of them is a valid choice, but this lister prefers Richard Burton’s as Henry VIII in Anne of the Thousand Days, the most regal, fearless, authoritative performance in film to date. As a result of the Academy’s decision, Burton lost once again, and eventually died without one, though he might have deserved two (The Spy Who Came in from the Cold). The Academy has been accused of denying many deserved wins and nominations throughout the 1960s and 1970s from British actors, in order to honor more Americans.