Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Top 10 Revolutions Felt Around the World

A revolution (from the Latin revolutio, “a turnaround”) is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes place over a relatively short period of time. It is mostly used to refer to political change. Revolutions have occurred throughout human history and vary widely in methods, duration, and motivating ideology. Their results include major changes in culture, economy, and socio-political institutions. Here are what I consider to be the ten most influential revolutions. I may have missed some important ones, so feel free to add yours. There is some overlap between this list and the list of significant coups d’etat, which is to be expected. Nevertheless, this list adds more information and a different perspective to the first…

On 22 August 1791, the slaves of Saint Domingue rose in revolt and plunged the colony into civil war. The signal to begin the revolt was given by Dutty Boukman, a high priest of voodoo and leader of the Maroon slaves, during a religious ceremony at Bois Caïman, on the night of August 14th. Within the next ten days, slaves had taken control of the entire Northern Province in an unprecedented slave revolt. Whites kept control of only a few isolated, fortified camps. The slaves sought revenge on their masters through “pillage, rape, torture, mutilation, and death.” Because the plantation owners had long feared a revolt like this, they were well-armed and prepared to defend themselves. Nonetheless, within weeks, the number of slaves who joined the revolt reached approximately 100,000. Within the next two months, as the violence escalated, the slaves killed 4,000 whites and burned or destroyed 180 sugar plantations and hundreds of coffee and indigo plantations.

By 1792, the slaves controlled a third of the island. The success of the slave rebellion caused the newly elected Legislative Assembly in France to realize it was facing an ominous situation. To protect France’s economic interests, the Legislative Assembly needed to grant civil and political rights to free men of color in the colonies.

In March of 1792, the Legislative Assembly did just that. Countries throughout Europe and the United States were shocked by the decision of the Legislative Assembly, whose members were determined to stop the revolt. Apart from granting rights to the free people of color, they dispatched 6,000 French soldiers to the island.

Meanwhile, in 1793, France declared war on Great Britain. The white planters in Saint Domingue made agreements with Great Britain to declare British sovereignty over the islands. Spain, who controlled the rest of the island of Hispaniola, would also join the conflict and fight with Great Britain against France. The Spanish forces invaded Saint Domingue and were joined by the slave forces. By August of 1793, there were only 3,500 French soldiers on the island. To prevent military disaster, the French commissioner, Sonthonax, freed the slaves in his jurisdiction. The decision was confirmed and extended by the National Convention in 1794 when they formally abolished slavery and granted civil and political rights to all black men in the colonies. It is estimated that the slave rebellion resulted in the deaths of 100,000 blacks and 24,000 whites.

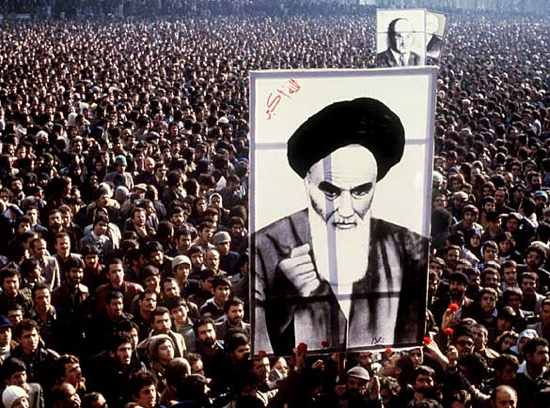

The Islamic Revolution refers to events involving the overthrow of Iran’s monarchy (Pahlavi dynasty) under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and its replacement with an Islamic republic under Ayatollah Khomeini, the leader of the revolution. The first major demonstrations against the Shah began in January 1978. Between August and December of 1978, strikes and demonstrations paralyzed the country. The Shah left Iran for exile in mid-January of 1979, and the resulting power vacuum was filled two weeks later when Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Tehran to a greeting by several million Iranians. The royal regime collapsed shortly after that, on February 11, when guerrillas and rebel troops took to armed street fighting and overwhelmed any troops still loyal to the Shah.

Iran voted, by national referendum, to become the Islamic Republic on April 1st, 1979, and later approved a new theocratic constitution whereby Khomeini became Supreme Leader of the country in December 1979.

The revolution was unusual, and it created a lot of surprise throughout the world: it lacked many of the customary causes of revolution (defeat at war, a financial crisis, peasant rebellion, or disgruntled military); produced profound change at great speed; was massively popular; overthrew a regime heavily protected by a lavishly financed army and security service; and replaced a modernizing monarchy with a theocracy based on the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists. Its outcome—an Islamic Republic “under the guidance of an 80-year-old exiled religious scholar from Qom”—was, as one scholar put it, “clearly an occurrence that had to be explained.”

On March 10th, 1952, General Fulgencio Batista overthrew the president of Cuba, Carlos Prìo Socarrás, and canceled all elections. This angered a young lawyer, Fidel Castro, and for the next seven years, he led attempts to overthrow Batista’s government. On July 26th, 1953, Castro led an attack against the military barracks in Santiago, but he was defeated and arrested. Although Castro was sentenced to 15 years in prison, Batista released him in 1955 in a show of supreme power. However, Castro did not back down and gathered a new group of rebels in Mexico. On December 2nd, 1956, Batista’s army was again defeated and fled to the Sierra Maestra. He began using guerrilla tactics to fight Batista’s armed forces, and, with the aid of other rebellions throughout Cuba, he forced Batista to resign and flee the country on January 1st, 1959. Castro became the Prime Minister of Cuba in February and had about 550 of Batista’s associates executed.

He soon suspended all elections and named himself “President for Life,” jailing or executing all who opposed him. He established a communist government with himself as a dictator and began relations with the Soviet Union.

The Cuban revolution was a turning point in recent history. With Castro’s regime in place, Cuba became an important source of support for the global power of the Soviet Union and thus affected the severity of the Cold War. Castro was involved in unsuccessful rebellions in Venezuela, Guatemala, and Bolivia, which caused Cuba to isolate itself from the surrounding world. The communist regime in Cuba gave the U.S.S.R. an ally neighboring the United States during the Cold War, thus bringing the threat of nuclear war to an all-time high.

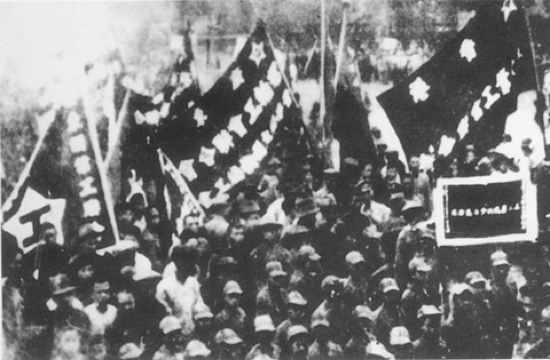

The Chinese revolution was a series of great political upheavals in China between 1911 and 1949, which eventually led to Communist Party rule and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. In 1912, a nationalist revolt overthrew the imperial Manchu dynasty. Under the leaders, Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek, the Nationalists, or Kuomintang, were increasingly challenged by the growing communist movement. The 10,000-km Long March to the northwest, undertaken by the communists from 1934 to 1935 to escape Kuomintang harassment, resulted in the emergence of Mao Zedong as a communist leader. During World War II, the various Chinese political groups pooled military resources against the Japanese invaders, but in 1946, the conflict reignited into open civil war. Mao’s troops formed the basis of the Red Army that renewed the civil war against the nationalists and emerged victorious after defeating them at Huai-Hai and Nanjing in 1949. In 1949, the Kuomintang were defeated at Nanjing and forced to flee to Taiwan. Communist rule was established in the People’s Republic of China under the leadership of Mao Zedong.

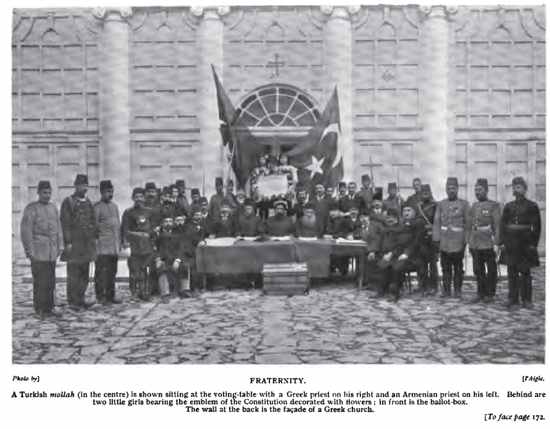

The Young Turk Revolution of July 1908 reversed the suspension of the Ottoman parliament enacted by Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who abdicated in a move that marked the return to Constitutional government. The Young Turk movement brought together various intellectuals and dissidents, many of whom were living in exile or as officers in the army, especially those based at the headquarters of the Third Army Corps in Salonika. Although it was inspired by the nationalist spirit sweeping through Europe at the time, which had already had cost the Empire most of its Balkan provinces, the movement promoted a vision of a democratic multi-national state. Some support for the movement came from Bulgarians, Arabs, Jews, Armenians, and Greeks.

The Revolution restored the parliament, which the Sultan had suspended in 1878. However, replacing existing institutions with constitutional institutions proved to be much more difficult than expected. Before long, power was vested in a new elite group led by the Grand Vizier. On the one hand, the movement wanted to modernize and democratize, while on the other, it wanted to preserve what was left of the empire. The promised policy of decentralization was abandoned when the leaders realized that this compromised security. In fact, the periphery of the Empire continued to splinter under pressure from local revolutions. Indifference from former allies such as the British, who, along with France, had ambitions in the region, compelled the Young Turks to embrace Germany as an ally to preserve the empire. Instead, this alliance led to the Ottoman defeat in World War I and the decline of their power. However, they laid some of the groundwork upon which the new nation-state of Turkey would be built, under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, himself a Young Turk.

The potential democratization project represented by the Young Turk Revolution had no parallel at the time among other imperial powers, such as the British and French, whose leaders were nowhere near contemplating granting self-determination to their African and Asian possessions.

The Taiping Rebellion was a large-scale revolt, waged from 1851 until 1864, against the authority and forces of the Qing Empire in China, conducted by both an army and civil administration inspired by the Hakka self-proclaimed mystics named Hong Xiuquan and Yang Xiuqing. Hong was an unorthodox Christian convert who declared himself the new Messiah and younger brother of Jesus Christ. Yang Xiuqing was a former salesman of firewood in Guangxi who was frequently able to act as a mouthpiece of God to direct the people, as well as gain himself a large amount of political power. Hong, Yang, and their followers established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (also, officially, Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace) and attained control of significant parts of southern China.

Most reliable sources put the total deaths during the fifteen years of the rebellion at about 20 million civilians and army personnel. However, some argue the death toll was much higher (as many as 50 million, according to one source). Some historians estimate the combination of natural disasters combined with the political insurrections may have cost as many as 200 million Chinese lives between 1850 and 1865. That figure is generally thought to be an exaggeration, as it is approximately half the estimated population of China in 1851. The war, however, qualifies as one of the bloodiest ever before World War II. It can be seen as a consequence of the collision between the imperial powers and traditional China; this introduced new concepts and ideals about governance and people’s rights, which clashed with existing customs.

While the rebellion had popular appeal, its eventual failure may have stemmed from its inability to integrate foreign and Chinese ideas, which, arguably, the twentieth-century Chinese leader, Mao Zedong, achieved with his brand of Marxism as “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

Also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution, this was a political revolution and part of the Russian Revolution of 1917. It took place with an armed insurrection in Petrograd on 25th October 1917 (Julian calendar), which corresponds with 7th November 1917 (Gregorian calendar). It was the second phase of the Russian Revolution, after the February Revolution of the same year. The October Revolution in Petrograd overthrew the Russian Provisional Government and gave power to the local soviets, dominated by Bolsheviks. The revolution was not universally recognized outside of Petrograd, and further struggles followed. This resulted in the Russian Civil War (1917–1922) and the creation of the Soviet Union in 1922.

The Bolsheviks led the revolution, who used their influence in the Petrograd Soviet to organize the armed forces. Bolshevik Red Guard forces under the Military Revolutionary Committee began to take over government buildings on 24th October 1917 (Julian calendar)). The following day, the Winter Palace (the seat of the Provisional government located in Petrograd, then capital of Russia) was captured.

To a large extent, the Roman Catholic James II (1633-1701), King of Great Britain from 1685 until he fled to France in 1688, brought the “Glorious” revolution down upon himself. When he succeeded his brother, Charles II, to the English throne, he alienated virtually every politically and militarily significant segment of English society by commencing ill-advised attempts to Catholicize the army and the government and pack Parliament with his supporters.

He employed the Dispensing Power (the royal prerogative allowing suspension of the operation of various statutes, declared illegal in the Bill of Rights of 1689) to evade the Act of Uniformity and the Test Act. His Declaration of Indulgence, issued in 1687-88, suspended penal legislation against religious nonconformity, allowing Dissenters to worship in meeting houses and Catholics to worship in private.

When he had a son in June 1688, fears of establishing a Catholic dynasty in England led prominent Protestant statesmen to invite William of Orange to assume the throne. William landed with an army at Torbay in November 1688, promised to defend the liberty of England and the Protestant religion, and marched unopposed on London. James fled ignominiously to France. Parliament then met, denounced James, offered the throne to William and his wife Mary as joint sovereigns, and placed constitutionally significant legal and practical limitations on the monarchy. A rebellion of Scottish Jacobites under Dundee threatened the rule of William and Mary, but Dundee himself was killed at the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689. The next year the Irish and French Jacobites, under James II, were defeated in Ireland at the Battle of the Boyne. As soon as William felt secure on the throne, after the Jacobite defeat, he brought England into the War of the League of Augsberg (versus France), which continued until 1697.

The American Revolution was a political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century. Thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America. They first rejected the authority of the Parliament of Great Britain to govern them from overseas without representation and then expelled all royal officials.

By 1774, each colony had established a Provincial Congress, or an equivalent governmental institution, to form individual self-governing states. The British responded by sending combat troops to re-impose direct rule. Through representatives sent in 1775 to the Second Continental Congress, the new states joined together to defend their respective self-governance and manage the armed conflict against the British, known as the American Revolutionary War. Ultimately, the states collectively determined that the British monarchy could no longer legitimately claim their allegiance due to its acts of tyranny. They then severed ties with the British Empire in July 1776, when Congress issued the Declaration of Independence, rejecting the monarchy on behalf of the new nation. The war ended with an effective American victory in October 1781, followed by formal British abandonment of any claims to the United States with the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

The American Revolution initiated a series of social, political, and intellectual transformations in early American society and government. Americans rejected the oligarchies common in aristocratic Europe at the time, championing, instead, the development of republicanism based on the Enlightenment understanding of liberalism. Among the significant results of the revolution was the creation of a representative government responsible to the will of the people. However, sharp political debates erupted over the appropriate level of democracy desirable in the new government, with a number of Founders fearing mob rule. Many fundamental issues of national governance were settled with the ratification of the Constitution of the United States in 1788.

The French Revolution was a period of radical social and political upheaval in both French and European history. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed within three years.

French society underwent an epic transformation as feudal, aristocratic, and religious privileges evaporated under a sustained assault from liberal political groups and the masses on the streets. Old ideas about hierarchy and tradition succumbed to new Enlightenment principles of citizenship and inalienable rights. The French Revolution began in 1789 with the convocation of the Estates-General in May. The first year of the Revolution witnessed members of the Third Estate proclaiming the Tennis Court Oath in June, the assault on the Bastille in July, the passage of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen in August, and an epic march on Versailles that forced the royal court back to Paris in October.

The next few years were dominated by tensions between the various liberal assemblies and a conservative monarchy intent on thwarting major reforms. A republic was proclaimed in September 1792, and King Louis XVI was executed the next year. External threats also played a dominant role in the development of the Revolution. The French Revolutionary Wars started in 1792 and ultimately featured spectacular French victories that facilitated the conquest of the Italian peninsula, the Low Countries, and most territories west of the Rhine—achievements that had defied previous French governments for centuries. Internally, popular sentiments significantly radicalized the Revolution, culminating in the Reign of Terror from 1793 until 1794, when between 16,000 and 40,000 people were killed. After the fall of Robespierre and the Jacobins, the Directory assumed control of the French state in 1795 and held power until 1799, when the Consulate replaced it under Napoleon Bonaparte.

The modern era has unfolded in the shadow of the French Revolution. The growth of republics and liberal democracies, the spread of secularism, the development of modern ideologies, and the invention of total war all mark their birth with the Revolution.

Subsequent events whose roots can be traced back to the Revolution include the Napoleonic Wars, two separate restorations of the monarchy, and two additional revolutions as modern France took shape. During the following century, France would be governed at one point or another as a republic, as a constitutional monarchy, and as two different empires.

The revolution was the result of complex political differences between the Republicans — supporters of the government of the day, the Second Spanish Republic, who mostly subscribed to electoral democracy and ranged from centrists to those advocating leftist revolutionary change, with a primarily urban power base — and the Nationalists, who rebelled against that government and had a primarily rural, more conservative power base.

The war for the revolution occurred between July 1936 and April 1939 (although the political situation had already been violent for several years before). It ended with the defeat of the Republicans, resulting in the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco. The number of casualties is disputed; estimates generally suggest that between 500,000 and 1,000,000 people were killed. Many Spanish intellectuals and artists were either killed or forced into exile; thousands of priests and religious people (including several Bishops) were killed. The more militant members of the population often found fame and fortune. The Spanish economy needed decades to recover.

The political and emotional repercussions of the war reverberated far beyond the boundaries of Spain and sparked passion among international intellectual and political communities. Republican sympathizers viewed it as a struggle between “tyranny and democracy” or “fascism and liberty,” and many idealistic youths of the 1930s who joined the International Brigades considered saving the Spanish Republic to be the idealistic cause of the era. Many gave their lives in its defense. Franco’s supporters, on the other hand, viewed it as a battle between the “red hordes” (of communism and anarchism) and “civilization.” However, these dichotomies were inevitably over-simplifications: both sides had varied, and often conflicting, ideologies represented within their ranks.