Politics

Politics  Politics

Politics  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Politics

Politics The 10 Most Bizarre Presidential Elections in Human History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Eggs-traordinarily Odd Eggs

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

10 Movie In-Jokes and Traditions

The movie business is now more than a century old – and in that time, numerous traditions and movie in-jokes have developed. These range from industry habits to personal calling cards from movie makers, which can all add a solid dose of interest to those with an appetite for movies.

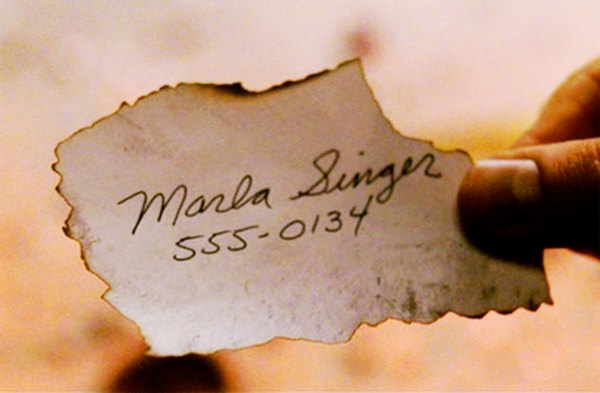

You may have noticed that in films where a telephone number is spoken or somehow visible, it almost always starts with ‘555’. This dates back to the 1960s, when some telephone companies in America set up a range of fictional telephone numbers for use in movies and TV shows. This was to avoid customers being harassed by coincidentally having the same telephone number that might appear in a film. For the most part, films abide by this guideline – though watch out if you live outside North America, because the 555 prefix is only protected in that region and may be a valid phone number in other countries.

Sally Menke was a film editor who had a long time association with Quentin Tarantino, working on all his films up until Inglourious Basterds before she passed away in 2010. Editing a film involves many hours sitting in front of a screen, assembling raw footage into sequence and trimming any fat until a film looks and feels as intended. The raw footage, apart from the obviously intended performances, often includes actors and crew in and around the set before and after the scene, for example, the director calling ‘action’ and ‘cut’.

As a thoughtful gesture for Sally, slaving away on the rough cut in the editing suite, cast and crew would often wave at the camera at the start and finish of the take, and say ‘Hello Sally!’ – sometimes adding a message of their own to keep her amused during her work.

Often included as a nod to a small section of the audience, to be overlooked by the rest, cameo appearances involve someone of significance making a brief and unexpected appearance in a film, often without saying a single line. Some directors are particularly known for this – Alfred Hitchcock probably more than anyone, having walk-on parts in most of his own films.

Quentin Tarantino also likes to appear in his own films – though he often plays a more significant, albeit supporting, role.

Pixar, a studio that specializes in animated films, has developed a tradition of referencing their own movies, characters, and employees throughout their work. This started back when it was producing short animations, and has continued on through all their output.

I could explain all the references, but maybe rattling off a quick list would be easier: John Ratzenberger, everybody’s favorite bar fly from Cheers, has had a role in every Pixar film since he voiced the grumpy Hamm in Toy Story; the books on the shelf in Andy’s room in Toy Story bear the names of Pixar short films; a Buzz Lightyear toy is visible in the dental surgery in Finding Nemo; a Pizza Planet truck (again from Toy Story) shows up in most other Pixar films; and the Luxo bouncy ball (from one of their shorts) often appears in the background somewhere.

Maybe the easiest self-reference to spot is the text ‘A113’. It is a reference to the animation class that John Lasseter and Brad Bird attended, and it appears in all Pixar movies and some other work directed by Brad Bird. You can see it on license plates, serial numbers of objects, train numbers, room numbers, and even in the spoken words of some characters.

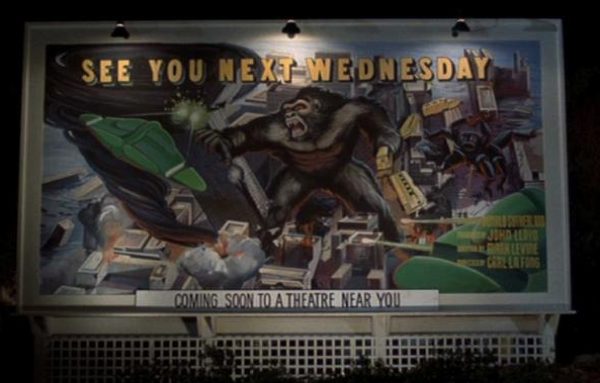

Featured in most films by John Landis is a reference to a non-existent film called ‘See You Next Wednesday’. First appearing in the film Schlock in 1973, and afterwards in Blues Brothers, Trading Places, Twilight Zone (a movie partially credited as an Alan Smithee – see number 2), and An American Werewolf in London, to name a few.

Some actors, whether intentionally or otherwise, become so identified with a type of character that they find it hard to break away and become known for anything else. A list of examples might include William Shatner as Captain Kirk, Hugh Grant as the bumbling English romantic, or Samuel L Jackson as the cool bad-ass. However, there are a few actors who – though not exclusively – seem determined for their character to die in as many films as possible.

Gary Oldman, Michael Biehn, Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro, Steve Buscemi (who always seems to get the grisly deaths), and Gary Busey, have all made a habit of dying before the credits roll. But I can’t think of any actor who has popped his clogs on screen more than Sean Bean, who has around 20 film deaths to his name. These include (spoilers alert!) Golden Eye, Patriot Games, The Lord of the Rings, The Island, Equilibrium, Outlaw, Essex Boys, Far North, Don’t Say a Word and The Field – the latter of which sees him killed by a cow. South Park’s Kenny would surely be near the top, if we were to include TV shows.

To make the process of adding sound effects a little less tedious, there are collections of stock sound effects that film makers use to fill particular requirements. An example might be the sound of a rusty gate opening, a distant explosion, thunder… or a faceless baddie’s death rattle.

Something called the ‘Wilhelm Scream’ has become a frequently used audio sample for use whenever the evil henchman/soldier/unlucky bystander happens to meet his maker. It was named after the character ‘Private Wilhelm’ from the 1953 Western The Charge at Feather River, though it was actually first used two year previously in a film called Distant Drums.

The Wilhelm Scream was popularized by sound engineer Ben Burtt, who used it initially (and repeatedly) in Star Wars, and many other George Lucas and Steven Spielberg films. Several other film makers started using it in their work and it has now spread to most action films, and even TV and video games. Once you know what it sounds like, you’ll start hearing it everywhere.

Ever since this was pointed out to me, I haven’t been able to miss it. Films seem to have an obsession with using orange and blue images, shades, and backgrounds on posters and artwork. I’ve read a little about color theory in art – and according to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s color wheel, blue and orange are complementary to each other. As are red and green, and yellow and violet.

When used together, complementary colors are naturally aesthetically pleasing, which is important for attracting people’s attention to a movie through its poster or DVD cover. There are many interpretations of exactly what emotions orange and blue are meant to evoke, but some say orange makes us imagine excitement and vitality, whereas blue has calming and cool mood. Whatever their meaning, movie promoters seem to believe that they have the desired effect – and if you look through the covers of your film collection, you may find a pattern emerging.

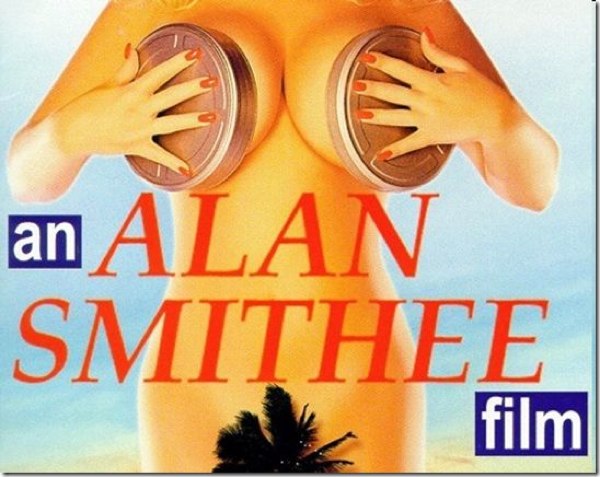

When creative control of a movie has been taken away from a director, they could ask to be credited as ‘Alan Smithee’. This first happened with the 1969 film Death of a Gunfighter which was initially under the direction of Robert Totten, before being taken over by Don Siegel after Totten was fired midway through production.

Neither director wanted to take credit for the film, and argued that the lead actor Richard Widmark had been the de facto director throughout the whole production. To solve the problem, the movie’s direction was instead credited to Alan Smithee. Despite not being a real person, he allowed everybody to save face without attracting attention, the name being both unique, yet ordinary.

Directors Guild of America rules also stated that directors receiving the protection of an Alan Smithee credit were not allowed to discuss their motivations for removing their identity from a movie in the press. As a consequence, Alan Smithee was, for a time, believed to be an actual director, although word eventually got around regarding the pseudonym and its real purpose.

Extending the profitability of a story by making sequels is nothing new. Novels were doing it long before film, with the first movie sequel being Fall of a Nation in 1916, the follow up to the technically brilliant but incredibly racist Birth of a Nation. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with the idea of sequels: some have been excellent, including Godfather II, Aliens, Toy Story 2, and The Dark Knight.

Sometimes, however, sequel-making comes across as little more than a cynical business endeavor (how dare movie studios want to make money?!). I’m not sure we really needed a Rocky V, Jaws: The Revenge, or Oceans 13. The same goes for prequels: Hannibal Rising and The Thing (2011) didn’t really do anything to elevate their respective series. Increasingly, there is also habit of spacing out a movie series, with some sequels having parts 1 and 2 (Harry Potter, Twilight), or being stretched into a trilogy (The Hobbit), or each character being given their own introduction movie (The Avengers).