Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

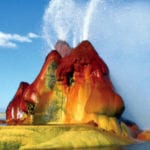

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Bizarre Stomach Churning Natural Remedies

For much of mankind’s history, doctors fumbled in the dark when it came to medicine. So much about disease and illnesses was unknown. One thing was understood: the human body has an amazing capacity to heal itself given time and opportunity, but when the condition just wouldn’t go away, it was time for intervention. Quite often, that meant something deeply unpleasant for both doctor and patient, as will be seen in these 10 weird natural remedies that may make you feel a bit sick.

Caveat lector: These so-called “cures” are complete nonsense at best, revolting, dangerous, unethical, and/or poisonous at worst. Do not, under any circumstances, try these at home or anywhere else. And if you don’t have a strong stomach, don’t read any further.

This comes from a seventeenth century book of medical advice: to cure toothache, take a live mole, pop it into a brass pot, clap on the lid, and let it die an agonizing death from dehydration and/or starvation. Once the poor creature’s suffering is at an end, chop up its tiny, furry corpse, remove the innards, and dry the rest near the fire. Hold the now mummified mole parts to your sore face. Don’t have the guts to listen to the mole’s desperate struggles to escape your cruel trap? Another book advises cutting off the foot of a live mole and hanging it around the neck. This method was also used to try and soothe teething babies. Nothing says, “Mommy loves you,” quite like freshly mutilated animal parts.

A traditional ingredient for ringworm and wart treatments, “fasting spittle”—the first saliva in the mouth on waking in the morning—was also used for eye inflammations. If it was good enough for Jesus Christ (Mark 8:23-25), doctors reckoned it was good enough for them. The spit was applied directly to the inflamed eye. Not necessarily the patient’s own spit, mind you. Could be the doctor felt the urge to work up saliva and try his luck. Or a total stranger might be brought in to donate to the cause. Not in the mood to have someone spit in your eye? How about snail slime? Or better yet, the fluid left after boiling snails alive in vinegar. Yum.

There may come a time when a child is being weaned that a nursing mother wants to dry up her breast milk. Or perhaps the new mom doesn’t want to breast feed at all, but Mother Nature has other plans. In some parts of nineteenth century Europe, women with milk swollen breasts turned to “smith’s water”—the bucket of water used by blacksmiths to quench their red-hot implements—as the quickest way to accomplish their aim. The water was splashed on the breasts and left to air dry. Supposedly, the water had somehow become charged with heat from the smith’s forge, and heat makes things dry, right? Incidentally, smith’s water was also used as a treatment for runny sores, most likely under the same principle.

Gout is a painful condition, no doubt about it. However, the logic of combating pain with pain escapes me, but it didn’t escape the physicians of old, who recommended patients suffering from gout whip themselves with stinging nettles until their skin was inflamed and blistered. Some patients preferred to have a servant whip them, or the doctor himself would see to the treatment. Or perhaps the very friendly lady down at the local bordello would have an enthusiastic go at urtication for just a few extra dollars. Did it work? No, but it took your mind off your troubles by giving you something else to cry about.

Suffering from bleeding, swollen, decaying gums and loose teeth? Tooth brushing and dental hygiene weren’t commonplace in the eighteenth century, and dentistry consisted mainly of yanking or chiseling out rotten teeth while the patient screamed in agony. However, help was at hand for the brave of heart or those desperate to try all natural remedies available for relief – no matter how bizarre. A French doctor of the time advocated gargling with urine to cure gingivitis. The patient’s own morning urine, of course. Unless there was a baby handy, or a woman of respectable habits, and one could get fresh, warm urine straight from the source. While some believe urine has antiseptic properties, the idea of gargling with pee doesn’t fill most of us with enthusiasm.

In previous centuries, doctors reached for the syringe—the clyster or enema syringe, not the hypodermic—to treat a number of illnesses. The “medicine” injected into the poor patient’s bowels varied depending on the effect the physician wished to produce. Not just water, but broth, ox gall, opium, wine, tea, even tobacco smoke might be introduced. For sufferers of liver complaints such as cirrhosis, the go-to remedy was a series of urine enemas. Not the patient’s, but whatever urine the doctor could scare up. For severe cases, the clyster syringe was filled with a blend of urine and strong coffee to grant a caffeinated jolt of healing power. Imagine of they put that on the Starbucks menu. Extra whip, anyone?

To treat jaundice in the eighteenth century, a perfectly respectable white wine was ruined by adding a quantity of sheep’s droppings and creating an alcoholic tincture of poop. Sheep’s poop, to be precise. A wineglass of this concoction, enlivened by the addition of saffron and turmeric, was gagged down by the patient at night before retiring. The pharmacopoeia notes that the patient should take care to avoid catching a cold as the medicine “doth incline a little to sweat.” If you knew you had to drink a glass of sheep shit right before bedtime, wouldn’t you be covered in flop sweat? Of course, if this is too much trouble, just add some fresh sheep’s dung to a cup of beer or ale, leave to steep overnight, and chug down the reeking mess in the morning. Breakfast of champions, I’m sure.

“Pine honey”—an old fashioned name given to the secretions of a species of aphid, or in layman’s terms, bug poop—was mixed with sarsaparilla and assorted flowers to produce a medicinal syrup that was supposed to purify the patient’s blood. This was believed to be especially effective when used in conjunction with purging. The administration of strong laxatives kept you clamped to the chamberpot or the seat above the cesspit (if you were lucky enough to have one) in an era before flush toilets or squeezable soft paper. Perhaps after much mighty purging, you no longer cared if the doctor spooned insect excrement into your mouth. Would you feel purified? Not necessarily, but you’d certainly be empty and left with the lingering sweetness of bug poop on your tongue as you sprawled, spent, on the potty chair.

In the seventeenth century, if you suffered from an annoying, persistent cough, the best remedy could be found in your garden. Slugs and earthworms “of middling size” were bruised by being lightly mashed with a blunt instrument. The worms were cut up alive, then added with the slugs to a pot of spring water, brought to the boil, and poured over candied sea holly root. If slugs were unavailable, ordinary snails would do, but the doctor had to fish out the shells afterward. A pint of this dubious liquid was added to a pint of milk and drunk by the patient. The concoction was also said to cure consumption, another name for tuberculosis. Straining out the bits of invertebrate corpses was optional.

No inhalers for asthma sufferers in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Instead, physicians recommended swallowing a young frog each day. A live frog. Well buttered, should the patient have difficulty choking the struggling amphibian down their gullet. Lends new meaning to the phrase, “a frog in your throat,” doesn’t it? A slightly less traumatic (or more, depending on your point of view) version was to bind a live frog to the patient’s throat and leave the frog to fight hopelessly for its life until it finally expired. The prolonged death agonies were supposed to help the condition. If the patient was unable to handle the frog, a handful of live spiders—nice, fat, juicy ones—might do the trick equally well of swallowed alive and kicking their eight little feet in protest.

Clearly, the cure can be worse than the disease, especially in your great-great-great grandparents’ day. Thank goodness modern medicine has evolved beyond pee drinking and poop eating … although leeches and maggots are making a comeback, I hear.