History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Weird Foods Sold By Victorian Street Vendors

In our plush, modern lives – with delicious stuff like bacon pizza with extra bacon and a side of bacon available at the touch of a cell phone button – we’ve largely forgotten that our nineteenth century ancestors had it much harder. They had to eat some seriously weird foods.

Many lower-income families lived in tenements without kitchens or even fireplaces, making cooking impossible. Street food—the original fast food—sold by vendors kept body and soul together – though much of the fare seems odd by today’s standards. Here are ten weird foods you could purchase if you invented a time machine, and possessed a curious palate and a strong stomach.

Sheep’s trotters were sold either cold or hot. These delicacies were typically bought cheap by vendors from the slaughterhouses, skinned and parboiled at their home, before being sold on the street. Customers would purchase a whole trotter, and suck the sticky meat and fat off the bones. If you were lucky, the vendor cleaned the nasty, dingy looking stuff from between the toes of the hoof before he cooked it – or at least before you ate it.

Eels were imported from Holland, cut into pieces, and boiled. The juices were thickened with flour and parsley, and the whole thing seasoned with pepper and kept hot for sale. A portion of meat was served in a cup (the liquor separately). Customers could add vinegar if they chose. A scrape of butter cost extra. A customer had to eat his snack quickly, since the vendor needed the cup returned. If you were lucky, the vendor would dip the cup in a bucket of dirty water before service. Most of the time, he didn’t bother.

Saloop had been popular since the 1600s. It was a hot and supposedly nutritious, heavily sweetened drink made from ground orchid roots. Towards the latter part of the nineteenth century, the basis of the drink changed to sassafras bark, flavored with milk and sugar. Regardless, saloop was considered a delicious and starchy way to start or finish the day. If you were lucky, the beverage was made with the proper roots or bark, and not something like used tea leaves picked from the trash heap.

Basically a carbohydrate bomb, plum duff was a British-style boiled “pudding” or dessert resembling a dampish dough. The plum part of the name comes from the raisins sprinkled throughout. A somewhat gluey experience – yet it was loved by working class children and adults more concerned with filling their bellies than having a nutritious meal. Adding a trickle of treacle cost extra. If you were lucky, the raisins were dried fruit rather than mouse droppings.

Most types of shellfish could be bought for practically nothing. Of course, shellfish has a distressing tendency to go off quickly – hence the popularity of pickling to preserve the goods as long as possible. When shellfish was sold fresh, about half of the customers preferred to eat it raw and still alive as opposed to boiled. If you were lucky, the oysters, whelks, etc., were relatively fresh when they went into the pickling solution.

Regular cow’s milk was available in summer from vendors who had the animals on the street, udders ready to deliver. They also purchased skim milk from dairies for resale, carrying pails or milk cans in yokes across their shoulders. However, some customers preferred richer, more exotic beverages such as donkey’s or asses’ milk. A few women believed drinking this milk – or eating curds and whey (cottage cheese) – made them appear more youthful. If you were lucky, you got actual dairy – not a mixture of chalk and water.

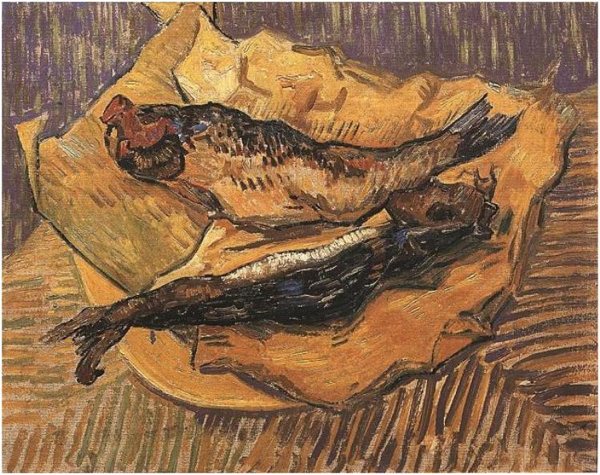

A bloater (common enough to be painted by Van Gogh above) was a salted herring, cold smoked whole – head, eyeballs, guts and all. Hence the bloating. Vendors would impale the fish on a long fork and “toast” over a flame to cook it before selling to customers who consumed the whole gamey, soft, flabby thing.

If you were lucky, the fish had roe in its belly cavity. If you were really lucky, the fish fell off the fork, a stray cat stole it, and you didn’t have to eat it.

The original ginger beer was a mildly alcoholic beverage made by boiling water with ginger and sugar, adding yeast, and flavoring with citric acid and cloves. It was generally bottled and sold within a couple of days. Mild fermentation could be achieved in as little as twelve hours, in a pinch. The cheaper “playhouse ginger beer” was sweetened with molasses. Vendors made the drink at home, where if you were lucky, they brewed it in something other than the washtub used by the wife for boiling the baby’s dirty diapers..

Rice “milk” was made by boiling rice in … that’s right, skim milk. A cupful was served hot with a spoonful of sugar and a sprinkle of allspice. The dish resembled a very thin, watery rice pudding. Cheap to produce, it was often sold by female vendors from a metal basin over a charcoal fire. Once again, customers consumed the portion while standing in the street. If you were lucky, the vendor wiped off the spoon before you ate with it..

Though technically not a street food, I had to include this one on the list. Tuberculosis – then called consumption – was rampant at the time. It was believed that the fresh, hot blood of a slaughtered animal would build up the sick person’s constitution, alleviating the disease. Consumptives would line up in the slaughterhouse with cups ready to catch the blood, which was swallowed right away. If you were lucky, the animal was dead when the collecting began.

Meat pies were a popular street food. The meat was usually mutton, or occasionally scraps of beef (the gristly, rubbery, and/or wobbly bits nobody else wanted to buy). Pie vendors complained that people mocked them by calling out, “Meow! Meow!” when they passed. Henry Mayhew’s work, London Labour and the London Poor (1851) records one such pie vendor asserting that cats were hardly ever used anymore.

Lest you think the Victorian poor were the only ones to suffer from indigestion and heartburn (not to mention nightmares) as a result of eating weird food, the lower middle class also put some strange dishes on the table … but that’s a list for another day.