History

History  History

History  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

History

History History’s Ten Most Lopsided Battles Ever

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

10 Embarrassing Blunders in US Military History

As impressive as popular portrayals of American military might and triumph may be, the non-airbrushed version of United States’ military history is actually even more remarkable. Specifically, that the US managed to survive its own blunders, boners, gaffes, and general bungling. Here are the highlights . . . or lowlights, depending on your perspective.

Technically, the Jumonville incident occurred before the United States even existed, but considering the main player was future president and all-American gangster George Washington, we think it deserves a place on this list. The young colonel served in the Virginia militia and his first assignment was to strengthen the British claim to the Ohio Valley. Because it was 1754, that meant building forts at critical river junctions.

That was all fine and good, but the French wanted the Ohio Valley just as badly so they sent their own errand boy, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, on a diplomatic mission to build forts and stake claims. So what did Washington do when his native allies found Jumonville’s camp?

Naturally, Washington ambushed Jumonville’s party. Keep in mind, Britain and France weren’t at war. However, they sure had plenty to fight about after Washington took Jumonville prisoner and allowed his native guide to kill the French officer. Washington’s blunder kicked off the Seven Years’ War and led to his first real battle and defeat at Fort Necessity. If only there’d been a rule; something along the lines of “don’t shoot the messenger . . . .”

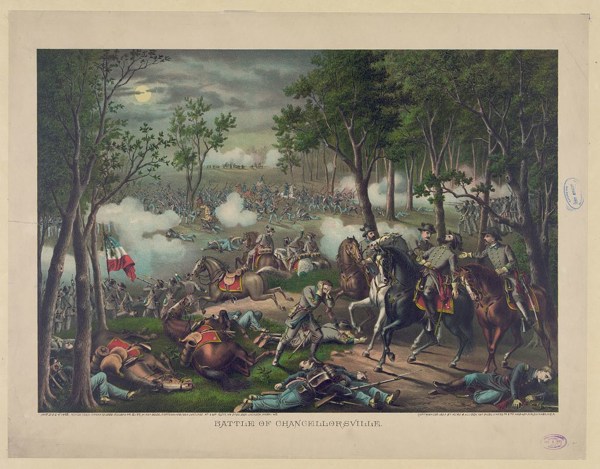

In an era that believed the rise of trench warfare to be an advancement, Stonewall Jackson was a rare beacon of tactical talent. Sure he fought for “slavery” or “states” depending on who you ask, but Jackson was the most reliably victorious general the Confederacy had. So much so that many people contend that Stonewall’s presence would have turned the tide at Gettysburg.

Jackson never made it to Gettysburg, though, thanks to his greatest victory, the Battle of Chancellorsville. During the battle, Jackson deftly moved around the battlefield to launch a surprise attack on the Union flank. Jackson and his 28,000 troops charged into Union soldiers who were playing cards.

When Jackson and his staff tried to return to their own lines, they were met by a nervous Confederate sentry. Jackson could scarcely answer the sentry’s call of, “who goes there?” before he and his party were hit by a volley from Confederate rifles. One of the South’s ablest leaders was shot by fellow rebels mistakenly convinced he was leading Union cavalry.

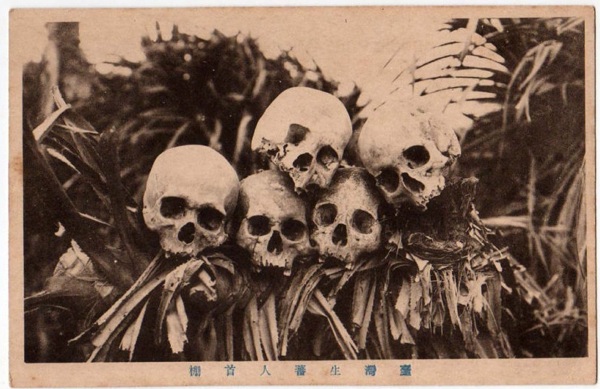

In March of 1867, two dozen American sailors washed up on Taiwan’s beaches. The native Paiwan people who found the sailors greeted the Americans in the traditional manner: beheadings for everyone. It was nothing personal—the Paiwan warriors greeted mariners of all nationalities in much the same way.

Three months later, the United States summoned up enough righteous indignation to address the “East Indies” situation. Local custom or not, those beheadings needed to be punished, and 181 US sailors and marines landed at Taiwan, June 13, 1867.

The US force marched into the jungle, planning to take any Paiwan villages—that is, if they could find them. All the Americans found was a series of ambushes. The Paiwans never allowed the Americans to close in, and few Americans even glimpsed the enemy. The day-long game of cat and mouse saw just a single casualty: Lieutenant Commander Mackenzie. At this point the Americans fired one last volley in the general direction of the natives, and high-tailed it back to the ship.

Like a clingy girlfriend, Britain just couldn’t accept its Revolutionary break-up with its former colonies. The British surrendered in 1781, but they sure as hell weren’t leaving New York anytime soon. Almost a full year after the treaty was signed the British army was still in New York City.

But George Washington’s main concern wasn’t getting the British out of New York City. He really wanted the British out of their Great Lakes forts, especially Fort Ontario, so Washington ordered a surprise attack to take the upstate New York fort. Five hundred Americans under Colonel Marinus Willett reached Oswego Falls, just four miles from Fort Ontario in February of 1783. Willet’s men marched the rest of the way through the woods to conceal their late night advance. There was just one problem—the Americans couldn’t find Fort Ontario.

By dawn the next day, Willet and his men had been walking in circles for over four hours and were still nearly a mile away when they spotted the fort from a small overlook. The element of surprise lost, Willet and his men retreated without firing a shot. And as for the British? They decided to keep Fort Ontario for thirteen more years.

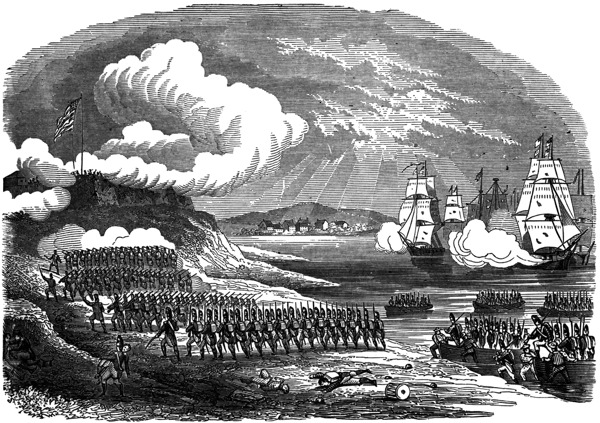

When the US went to war with Great Britain in 1812, the UK was also contending with the looming spectre of a completely Napoleon-dominated Europe.

The US army pretty much assumed taking Canada from Great Britain would be about as taxing as a brisk march. The invasion took the form of a large American militia under William Hull, who attempted to invade Canada via Ontario. While on the march, rumours of large native forces on the warpath spread, and panic infected the American militia. The invasion of Canada turned into a full-on retreat back to the warm confines of Fort Detroit.

The British then laid siege to the fort with less than half the number of its defenders. The British told the garrison that the native warriors would show no mercy if Fort Detroit did not surrender; the defenders immediately surrendered to the tiny British force and headed home.

In 1780, the Revolutionary War was not going well for the rebels in the south. The Continental Army’s strength was rapidly dwindling due to an amazing ability to find defeat whether attacking or defending.

Faced with a British army 11,000 strong and twice the size of his own, American commander Benjamin Lincoln moved his 5,500 men behind the reassuring walls of Charleston, South Carolina. With that one decision, Lincoln effectively ended all American resistance in the state.

The city of Charleston lies between two rivers on what is essentially a peninsula. General Lincoln chose to make his stand at the point of said peninsula, allowing British land forces to cut off any possible chance of escape inland and exposing his army on one side to bombardment from the greatest navy in the history of guns-on-ships. Predictably, Lincoln surrendered. This wasn’t just any old surrender, though. Until the Battle of Corregidor in 1942, it stood as the single largest surrender in the American Army’s history.

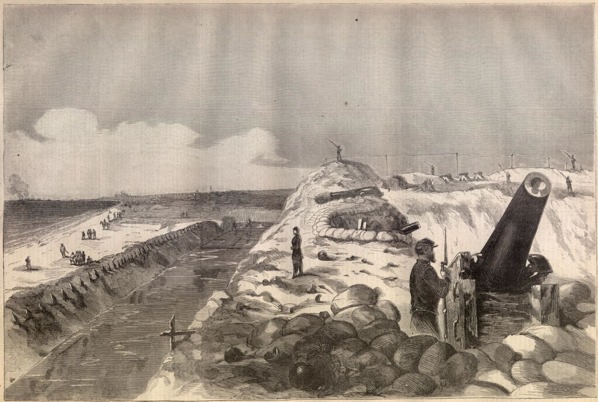

One hundred and eighty. That’s how many British soldiers and marines held off over 4,000 American attackers in 1814, forcing their retreat. The Second Battle of Lacolle Mill almost makes other American efforts during the War of 1812 seem laudable. To be fair, the mill-house near Champlain, New York where the British forces were garrisoned was of stout stone construction.

On the afternoon of March 30, American artillery fired upon the garrison at Lacolle Mill, but failed to do anything besides make a lot of noise. British sorties forced the Americans to abandon their artillery multiple times. Somehow, the defenders managed to repulse all the infantry charges. The only trouble for the British was a dwindling supply of ammunition. By six o’clock that same evening the American army had hastily retreated eastward.

While the defenders suffered sixty-one wounded or killed, the British had managed to reduce the American strength by some 264 casualties. Not surprisingly, Lacolle Mill was the last battle American General James Wilkinson directed, as he was mercifully relieved of command thereafter. Standards were pretty low during the War of 1812. Merely having a pulse may have been enough to qualify you to lead Americans to their deaths.

How many Americans does it take to catch a Mexican bandit? At least 5,000, because John Pershing and his 4,800 American troops spent the better part of 1916 chasing Pancho Villa around Northern Mexico with almost nothing to show for the effort.

Pershing spent eleven months trying to capture Villa who had been raiding American border towns. Despite failing to complete his sole objective, Pershing was undeterred and in an enormously ballsy PR move declared the mission a great learning experience (and thus actually a success). Apparently, Texans ate that “learning experience” garbage up, since Pershing’s expedition was greeted by large crowds and applause upon their rather un-victorious return to El Paso.

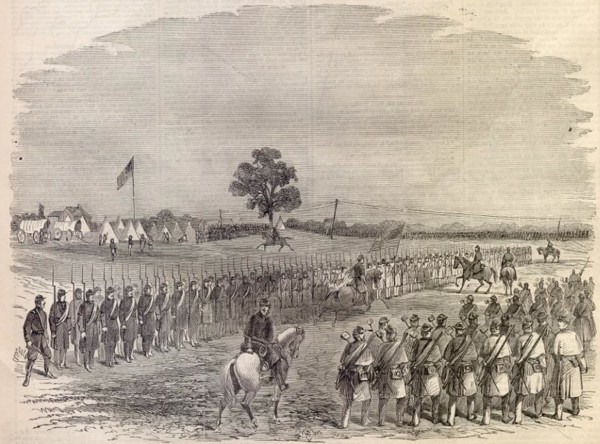

The Civil War was at a grind in 1864. In Petersburg, Virginia, both the Union and Confederate armies were entrenched amidst a stand-off. Union leaders had a somewhat brilliant idea: dig a long tunnel underneath the Confederate position, blow it up, then attack while the Confederate lines are in disarray. The first two thirds of the above plan went off without a hitch, until the Union tried to press its advantage and attack.

First, it took almost fifteen minutes for the Union to mount its attack. Then the scaling ladders needed to climb out of their own trenches failed to materialise. But the real kicker was the attack itself. Instead of charging around the massive smoking crater, inexperienced Union troops jumped into it under the mistaken belief the crater offered good cover. By doing this, the union had graciously abandoned any advantage they might have had for a lower position than the enemy (generally a bad idea). The Confederates rallied and aimed their artillery at the massive hole in which the Union troops had put themselves. Shooting fish in a barrel makes it sound more difficult than it was, and it was made even easier when the Union counter-attack failed to flank the Confederates . . . and took cover in the crater.

Only about half of the 8,000 Union troops involved survived the battle unscathed. When all was said and done, both sides returned to their trenches and sat there for another eight months.

By now it should be obvious that the War of 1812 was comedy at its finest (minus all the deaths). The Battle of Bladensburg is the cherry on top of the American embarrassment sundae.

In 1814, the British were looking to end this farce of a war and naturally laid eyes on the American capital of Washington, DC. As many recently-arrived British reinforcements were veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, Britain definitely possessed a significant troop-quality advantage. The Americans would have to beat them with numbers.

American militia numbering 6,000 met 4,000 British veterans at Bladensburg just eight miles from DC, the British fired Congreve rockets—glorified fireworks—which scared the American troops who held firm just long enough to fire a couple of volleys before taking off running. And run they did. The US lost just ten or twelve men, but almost all of its pride. That night Washington burned, thanks to the American inability to delay the British advance by even a few hours.

The hasty, disorganised American retreat has been called “the most humiliating episode in American history.”

You can read more from J. Wisniewski at The Independent Reflector