Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Little-Known Technological Firsts

When we think of “technology,” we generally think of our PC, or smartphone, or electric nose hair trimmer. (We really like those.) But we tend to forget that the most mundane, taken-for-granted things were once cutting-edge technologies, and that the world didn’t come pre-populated with cars, radios, and car radios. Here are ten interesting technological firsts:

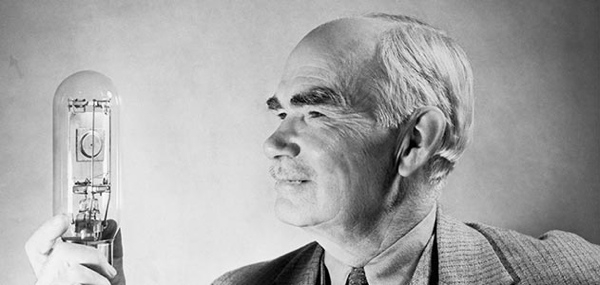

Lee DeForest didn’t exactly invent radio—no one person did that—but he did invent the Audion, which greatly improved the existing technology, He also coined the term “radio,” which has stuck around for quite some time now. In 1907, DeForest was experimenting successfully with ship-to-shore radio communication, and claiming that he’d soon be broadcasting opera performances to all of New York City—and in 1910, he actually did it.

The first public radio performance was broadcast on January 13 of that year, from the Metropolitan Opera House, with performances of Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci, featuring famed tenor Enrico Caruso. The signal was broadcast with a five hundred watt transmitter, and was heard as far away as Bridgeport, Connecticut.

While the quality was obviously poor (with the New York Times reporting that the static “kept the homeless song waves from finding themselves”—whatever that means), reporters were nevertheless impressed, and interest in the medium immediately began to grow.

Mary Ward was a female scientist at a time when they practically didn’t exist. She was fascinated with . . . well, tiny things—and as a child would draw ants and other insects in great detail using a magnifying glass. She soon moved on to microscopes, and by her twenties was publishing her sketches of tiny things; her first book was appropriately titled “Sketches With The Microscope.”

Mary’s family had a strong scientific bent, too: a couple of her cousins built an early steam-powered automobile, which they liked to rumble around in at hell-raising speeds approaching five miles an hour. Out on a ride with them one day, Mary was thrown from the car while it was going around a bend; she fell directly under a wheel and broke her neck, thereby becoming the very first automobile fatality.

While her death was certainly noteworthy, her life was as well. She was a pioneer in microscopy, and shattered a glass ceiling or two for women in the scientific community.

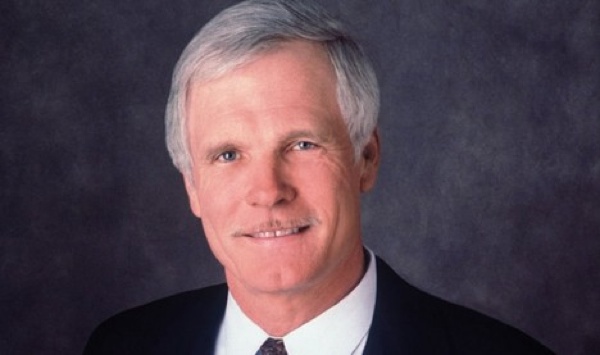

In 1972, HBO became the first pay cable network. It was also the first to use a newly approved satellite-based distribution system, distributing its signal to cable operators nationwide. It was the only station to use this distribution system until 1975, when a local Atlanta UHF station owned by one Ted Turner decided it wanted to play, too.

In 1972, HBO became the first pay cable network. It was also the first to use a newly approved satellite-based distribution system, distributing its signal to cable operators nationwide. It was the only station to use this distribution system until 1975, when a local Atlanta UHF station owned by one Ted Turner decided it wanted to play, too.

Originally called WCTG, Turner’s station became the first non-pay network to broadcast over satellite on December 17, 1976. Its signal was beamed to four cable operators in Nebraska, Virginia, Alabama and Kansas, and showed Deep Waters already thirty minutes in progress.

The station changed its call letters to WTBS (for Turner Broadcasting System) in 1979. It was the first “Superstation,” meaning a local station transmitted by satellite to cable providers. TBS minus the W is still part of most cable packages today, and it was the very first basic cable channel.

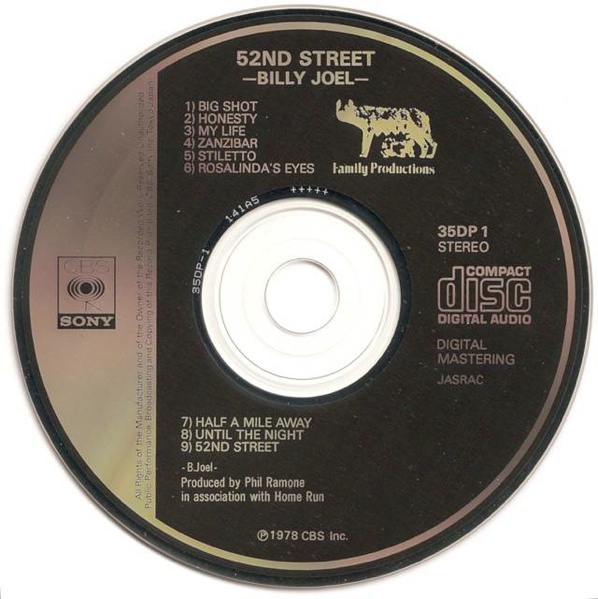

For many of you, the Compact Disc was the dominant musical format of your childhood. Vinyl records, the format of choice for over thirty years up until the ’eighties, were outsold by the CD for the first time in 1988, and CDs were not outsold by another format—digital releases (and just barely)—until 2011.

The CDP-101, the world’s first commercially-available CD player, was rolled out in Japan on October 1, 1982, and the first CD was released the same day: Billy Joel’s 1978 classic, 52nd Street. It would be another five months before any more titles (sixteen of them, all from the CBS Records catalog) would be released, coinciding with the US debut of the player.

Why Sony chose Billy Joel to introduce the technology to the Japanese public is a mystery, but they could have done worse—52nd Street contains now-iconic tunes like Big Shot, Honesty and My Life, and it’s a damn good album.

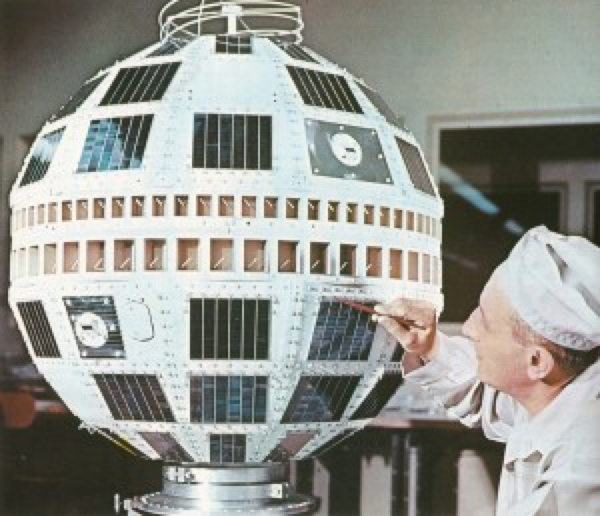

The first privately-sponsored space launch on July 10, 1962, led to the first global television broadcast two days later. Telstar 1, a satellite owned by AT&T, was launched into orbit on that day by NASA at Cape Canaveral—the result of an unprecedented cooperation between those two entities as well as Bell (who built the satellite), the General Post Office of Britain, and France Telecom.

Images were relayed between Andover, Maine, and Brittany, France—and they were broadcast on both sides of the Atlantic for eighteen minutes. The first image was of a waving American flag, followed by portions of a press conference held by President Kennedy and shots of a Phillies-Cubs baseball game.

Telstar I handled hundreds of broadcast, phone, and fax transmissions for four months until cosmic radiation rendered it inoperable. This cosmic radiation came from the high-altitude nuclear test conducted by the US the day before its launch, which someone really failed to think through.

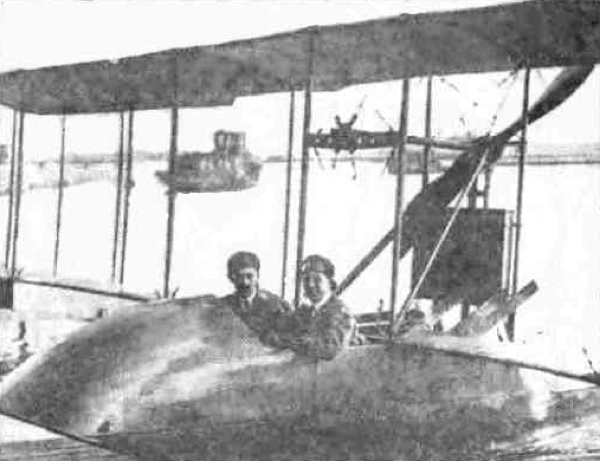

The first flight between two cities—and the first to carry a paying customer—was between St. Petersburg and Tampa, Florida, on New Years’ Day 1914. The journey, which would take a couple of hours by ship or at least four by train, lasted a scant twenty-five minutes or so; its passenger was St. Petersburg businessman and former mayor Abram Pheil (pronounced “fail”, we hope) who won the seat at auction and paid the modern day equivalent of five thousand dollars for the privilege.

The pilot, twenty-five-year-old Tony Jannus, was a barnstormer and test pilot for military aircraft, who was already a somewhat popular public figure; his involvement, and the buzz generated by the auction, combined to raise public interest in the “aeroplane” as a method of travel.

And we’re glad for that; going home for the holidays is enough of a pain without having to spend three days on a damn steamship.

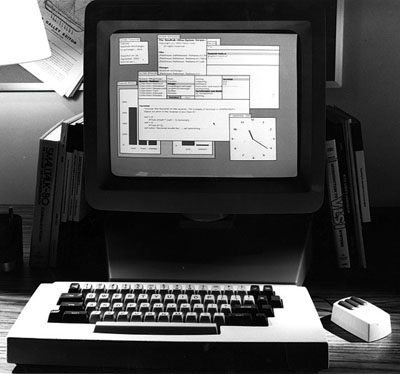

The first commercially available home computer with anything resembling a familiar GUI—a graphical user interface, with windows, folders and a mouse—was the Apple Macintosh in 1984, which was famously adapted (see: ripped off) by Microsoft for its Windows OS. But don’t feel too bad for Apple; the heavy lifting in designing the interface wasn’t done by their engineers, but by Xerox.

Xerox researchers internally debuted the Alto in 1972, and its features read like a list of everything standard in PCs today. Bit-mapped graphics, icons, windows, and the first-ever mouse—oh, and the Alto was also the first computer to feature something called an Ethernet local area networking protocol.

Being mainly in the photocopier business, Xerox chose not to bring the machine to market in order to focus instead on its bread-and-butter—a decision which every single player in the personal computer industry would roundly applaud years later.

In late 1977, Magnetic Video became the first company to market theatrical releases on Betamax and VHS videotapes. Their library consisted of fifty films—classics like Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid and The Sound Of Music—in both formats, and they quickly began doing pretty well selling their videos by mail order.

George Atkinson was the owner of Home Theater Systems, a Super 8 film and projector rental company in L.A. Already being in the business of renting movies, Atkinson had a bright idea: he plunked down a pretty decent amount of cash for one Beta and one VHS copy of each of Magnetic’s fifty titles, opened a tiny storefront on Wilshire Boulevard, and took out an ad in the L.A. Times announcing “Videos For Rent”—the first time anyone had ever done so.

The cost was initially steep: fifty bucks for a year’s membership, one hundred for lifetime’s, plus ten bucks a day for each rental (late ‘seventies money, remember). But the venture was a success, and Atkinson eventually licensed more than six hundred Video Station franchises—becoming the very first video rental chain.

Various inventors tried and failed to come up with a workable automated product scanning system throughout the ’fourties, ’fifties and ’sixties. In 1972, a Kroger in Cincinnati experimented with a “bulls-eye” style code—but at the time, a committee was being formed within the grocery industry to produce a standard. IBM’s proposal, for what would become known as the UPC or Uniform Product Code, won out.

The first ever UPC scanner was installed at one checkout station in a Marsh’s Supermarket in Troy, Ohio, in June of 1974. At 8:01 in the morning on June 26th, a ten-pack of Wrigley’s gum became the first item to ever be scanned. The very same pack of gum now resides at the Smithsonian’s National Museum Of American History, which begs the question: who bought the gum, and why didn’t they chew it?

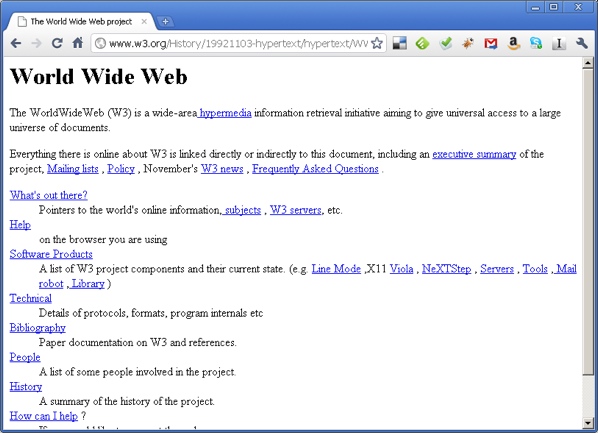

“The WorldWideWeb (W3) is a wide-area hypermedia information retrieval initiative aiming to give universal access to a large universe of documents.” So reads the text at the top of the first website ever to be published, by Tim Berners-Lee—the inventor of the World Wide Web—on August 6, 1991.

The page (originally at Info.cern.ch) was created on a NeXT workstation at CERN labs in Geneva, Switzerland. It pretty much just states that the “Web” is now a thing that exists, and lists some of the people involved with the project and some technical information.

Since nobody but Berners-Lee and his CERN colleagues had any software resembling web browsers, most of the outside world remained ignorant of this ridiculously monumental development until the Mosaic browser debuted in 1993.

The page has been preserved, and though it looks like something a grade schooler could whip up in ten minutes today, it led directly to every website that has ever existed, including the incredibly awesome one you’re reading right now. The server it resided on is still powered on at CERN to this day, with a sign reading, “This machine is a server. DO NOT POWER DOWN!”

Do not, indeed. Father of all web servers, we salute you.

There are more interesting lists on Floorwalker’s blog, and the cool kids follow him on Twitter.