Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

10 Ways Our Ancestors Made Murder Fun

Lacking a means of mass communication like television or the Internet, nineteenth century citizens had to learn about grisly murders the old fashioned way: by reading about it in the newspapers. But what about people who couldn’t read or had no access to the papers?

Canny entrepreneurs came up with various money-making schemes to inform the illiterate, lower class public as well as entertain them, making it easier to part them from their pennies. Here are ten ways your ancestors made murder fun for the whole family.

Writers of broadsheets often employed doggerel verse in these poorly printed, highly imaginative accounts of murders which were sold in poorer neighborhoods. Several editions focusing on the same murder might hit the streets within hours. Broadsheet sellers made sure to keep abreast of the latest developments on the investigation, arrest, trial, and eventual execution, often making up details about the crime or the killer’s contrite confessions on the gallows to satisfy their audience. Pamphlets could be equally fictitious in relating the details, but were generally a bit better written and printed. It wasn’t uncommon for a group of people to pool their money to buy a broadsheet or pamphlet to share.

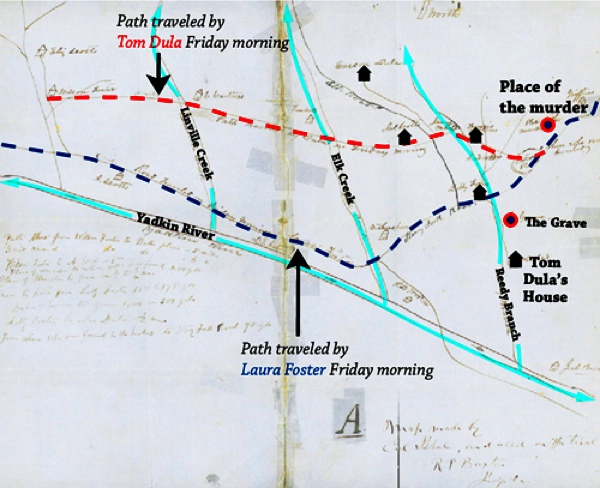

Songs about murders have been around a very long time. In the nineteenth century, song writers continued to take advantage of the public’s morbid fascination with murder by writing catchy topical tunes about killers and their victims. The music sheets were sold in shops and by vendors on street corners. Dance saloons played popular ballads for their customers. Individuals who could read music, but had no access to an instrument, sang the songs on the street to rapt audiences. The practice of writing and performing this kind of ballad hasn’t changed much in modern times. Ever heard “Tom Dooley?” That’s an enduring murder ballad. Joan Baez sang a few, too, including “Banks of the Ohio.”

Whether for the penny gaffs—a rough, cheap form of theater for poorer folk—or the more upscale playhouses frequented by middle class and upper class patrons, murder meant “bums on seats” for playwrights and actors. Of course, as in today’s television melodramas, the details were tweaked to make them more exciting. One incredibly popular play, “The Colleen Bawn,” was based on the murder of Ellen Scanlan by Stephen Sullivan in Ireland around 1819. The story has not only been turned into a play (1860), but a novel, an opera, and three films. The true tale of the crime is rather mundane, but writers spiced it up.

We think of marionettes as solely children’s entertainment, but in nineteenth century fairgrounds, these puppets on strings played out famous murders on their toy stages, delighting lower class children and adults alike. The effects were more sophisticated than you might expect, sometimes including pyrotechnics or spurting blood (actually an explosion of red ribbons from the puppet’s body). A perennial favorite was “Maria Marten, or the Murder in the Red Barn.” According to legend, the son of the unfortunate victim, Maria Marten, went to see a marionette performance of the drama and didn’t turn a hair.

In the days before licensing agreements, anything belonging to or having a connection with a murderer or victim was fair game. For example, a structure in which a notorious murder took place might be torn apart (not necessarily with the owner’s consent) by an ambitious entrepreneur, who sold the pieces as memorabilia. Wood from a crime scene might be turned into matchboxes or snuff boxes and put on sale. Even pottery companies got in on the act by producing figures of the major players and the scenes. In fact, bits of the murderer’s own body might be turned into keepsakes such as a cigar case or a pair of shoes. And handkerchiefs dipped in an executed murderer’s blood have always been collectible.

Before forensic science or autopsies were common, a murder victim’s body was often left in situ so the scene could be examined by the jury of a coroner’s inquest. While the police were supposed to guard the location, it often transpired that a member of the victim’s household (family, friend, or servant) would permit paying members of the public to enter and gape at the blood, the terrible wounds, the gore clotted murder weapon, footprints, and anything else that may or may not have relevance. These tourists might help themselves to whatever struck their fancy at the scene, such as door handles, drawer pulls, and textiles. Even after the body was removed, gawkers would continue to come and have a look.

If one couldn’t make it to the murder scene in person, the next best thing was viewing a model at a fair or from a street entertainer. The customer paid the fee, put his eye to a hole in the side of a wooden box, and was able to view a recreation of the crime scene in miniature. The luridly painted backdrops (complete with the victim weltering in his/her gore) could be changed while the operator recited the story of the crime, which might also include the murderer’s hanging. At night, the scenes were dramatically lit with candles. For some reason, nineteenth century newspapers sometimes called these exhibitions, “camera obscura.” These exhibitions remained popular until the invention of the mechanical peep show.

If broadsides, pamphlets, and ballads were too middle of the road, one only had to wait for the patterers or storytellers to come around one’s neighborhood. These men carried signs painted with exaggerated pictures of the victim, the killer, the crime scene, the courtroom, the prison, and/or the gallows. Patterers exhibited the signs to draw in people eager to hear the details. After collecting a large enough crowd and passing the hat for his fee, a patterer would tell the story of the murder in an entertaining way. From the police’s initial investigation to the killer’s last dance at the end of a rope, a good patterer never ran out of material.

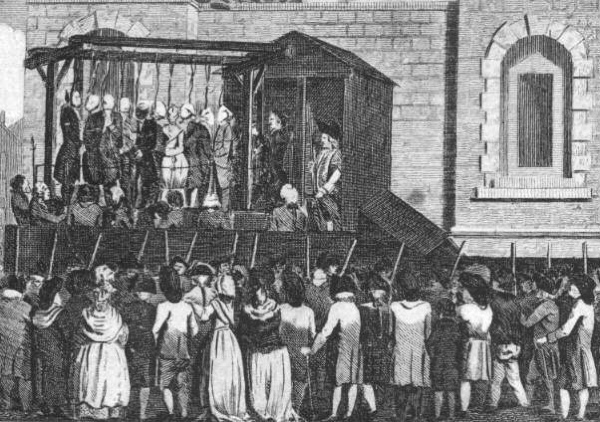

The execution of a murderer could bring thousands of people flocking to the gallows to see the hanging (until 1868, when a law was enacted to place all executions behind prison walls). Owners of buildings with a good view of the proceedings sold places to gawkers. Vendors of broadsheets, souvenirs, and food worked the crowd, as did pickpockets. If the hangman was inept or sloppy, the condemned man or woman might suffer slow strangulation (which could take up to fifteen minutes) instead of a quick neck snap, or might be decapitated, spewing blood everywhere. Afterward, there might be an auction of the dead person’s personal effects, and the rope would be sold by the inch. The body might be displayed for several days or given to the scientific community, which leads me to…

Apart from serving as fodder for medical dissection, some murderers’ bodies were experimented on, and sometimes the experiments were put on public view. Take William Corder, for instance, the killer of Maria Marten (mentioned in #7). Following his hanging, his body was placed on a cart and driven to the Shire Hall. His guts were removed by a doctor, and a plaster cast taken of his head to be studied by phrenologists. In addition, a battery was brought from Cambridge for the express purpose of performing “galvanic experiments” on Corder’s body. All these proceedings were witnessed by a fascinated public, some of whom walked thirty miles into town to see the execution and its aftermath.