Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Animals

Animals 10 Amazing Animal Tales from the Ancient World

Gaming

Gaming 10 Game Characters Everyone Hated Playing

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Animals

Animals 10 Amazing Animal Tales from the Ancient World

Gaming

Gaming 10 Game Characters Everyone Hated Playing

10 Fascinating Scientific and Psychological Effects

An effect describes an observable phenomenon where something causes another thing to happen; often, this cause is not fully understood. Well-known effects include the Greenhouse Effect and the Placebo Effect; but scientists, psychologists, and other researchers have far too much curiosity to stop at “well-known.” Have you ever wondered, for instance, why Cheerios tend to clump together—and head to the edges—when they float in a bowl of milk? Why do Brazil nuts always end up at the top of a jar of nuts? Why do your friends always think they’re right about everything? Why does the shower curtain stick to you? Read on!

Picture your last bowl of Cheerios (or other breakfast cereal)—do the Cheerios hang out alone, minding their own business, or do they tend to stick together? The natural tendency of small objects floating in water to attract one another—and to head toward the edges of the container—is called the “Cheerios Effect.”

The explanation begins with surface tension, the tendency of the surface of a liquid to behave like a type of shield (or perhaps more precisely, a flexible membrane), resisting penetration from floating objects. A Cheerio, which is denser than milk, will remain atop the surface of the milk with the aid of surface tension, but the level of the milk immediately local to the Cheerio will dip slightly, causing nearby Cheerios to behave the same way—basically, the fall into the slight dip caused by the first Cheerio. An object LESS dense than the liquid will float naturally, with or without the help of surface tension, and will head towards the edge of the container, seeking the highest point possible.

The Brazil Nut Effect—also known as “granular convection” or “The Muesli Effect”—is a phenomenon where, when a group of different-sized particles is shaken vertically, the largest rise to the top. The name comes from the tendency of Brazil nuts (usually the largest nut in a nut cocktail) end up at the top, resting on smaller nuts, after the can has been transported and shaken. This can seem counterintuitive, as one might expect the largest and heaviest to drop to the bottom and the smallest and lightest to rise to the top.

The effect was first studied in the 1930s, and though it’s fairly well understood, there are still certain questions that remain unanswered. A couple of separate forces are at work here: “percolation,” where smaller particles drop down through the relatively large spaces between larger objects, and “convection,” which drives those larger objects upwards (and also causes them to head towards the edges of the container when there’s nowhere higher to go). But at least one other mechanism may be involved—“condensation,” which is related to temperature—and there is also something known as the “reverse Brazil nut problem.” The roles of density and pressure are also still being studied.

Ah, the false-consensus effect. We’ve all been there, and we’ve all got acquaintances who are more susceptible to it than others—the cognitive bias whereby someone overestimates how much other people agree with them. Your friend who eats only raw, vegan food, and believes that others will necessarily leap at the opportunity to share their diet, is succumbing to the false-consensus effect.

In general, people have a tendency to internalize what they believe (as well as the ways they act, think, speak, and so on) as “normal” and correct. This is likely due in part to what’s known in psychology as the “availability heuristic,” the process of making decisions based on what immediately comes to mind. Given that we spend time with friend, family, and others who generally share many of our opinions and beliefs, this insular social grouping can contribute to the false-consensus effect.

It appears that the strength of the effect is increased when we have a high degree of certainty about a position, when what is being discussed or considered is deemed relatively important, and when the behavioral context of the “consensus” is amplified in some way.

Fill a mug with milk or water, then tap the side (or bottom) of the mug with a metal spoon—and listen to the pitch of the sound produced. Then, pour a packet of hot chocolate mix into the mug, and tap again—the pitch will have dropped significantly. Then, as the powder dissolves, the pitch of the sound begins to rise again. This is known as the “Hot chocolate effect,” and was first studied by physicist Frank Crawford in 1982.

Also known as the “allassonic effect,” the phenomenon is caused by the change of the speed of sound in the mug as the various new elements are introduced and as these new elements change. Specifically, the density of the bubbles created then the powder hits the liquid changes, causing a change in the sound that passes through them.

The Lake Wobegon effect, known more formally as “illusory superiority,” is another cognitive bias. So nick-named because the children in Garrison Keillor’s fictional town of Lake Wobegon are “above average,” illusory superiority is a phenomenon whereby people consider themselves to be better than others—in other words, above average—with regard to specific abilities, skills, performance, and intellect. This effect is seen quite commonly in drivers, who reliably consider themselves to be superior to other drivers on the road. In a 1981 study of drivers in the US and in Sweden, for example, 93% of the Americans polled rated themeless as above average drivers (compared to 69% of the Swedish drivers polled). With regard to how safely they drive, 88% of the Americans and 77% of the Swedes rated themselves in the top 50%.

Illusory superiority shows up in all kinds of places. Kids in school often inflate their relative popularity; people tend to think of their romantic relationships as better than that of others; people tend to think of their ability to get along with others as being above-average. Common traits that show up in studies of the effect include, among others, kindness, virtuosity, luck, and investing ability.

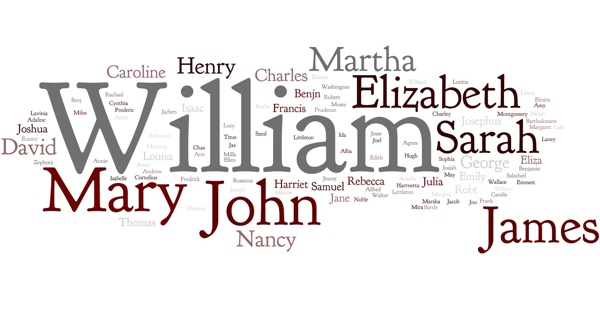

People tend to prefer the letters that appear in their names—particularly their initials—and this preference is called the “name-letter effect.” This may not be all that surprising, given how often we write and read the letters in our names; where the name-letter effect gets interesting, however, is how this shows up subconsciously in the strangest places. Controversial studies have suggested that there appear to be significant correlations between the letters in peoples’ names and certain life choices they make and successes (or failures) they experience.

For instance, a series of studies done at SUNY Buffalo found that people are more likely to live in cities and/or states with names that resemble their own, find jobs and careers that linguistically resemble their names, and perhaps even find mates that fit the same criteria. It’s also possible that the name-letter effect can have negative effects; Two professors, one from UC San Diego and the other from Yale, conducted studies that examined, among other things, whether baseball players with a first or last name that starts with K (the statistical symbol for a strikeout) were more likely to strike out than their peers. The report claims that “We found that our own-name liking sabotages success for people whose initials match negative performance labels.”

It should be noted that these studies are considered by many to be of dubious (at best) legitimacy and that the results may in fact be due to statistical artifacts (errors).

When you’re in total darkness—say, in the woods at night—and you see a small point of light, stare at it. After awhile, that stationary light will appear to move in front of you, despite the fact that it isn’t moving at all. This “autokinesis” is a visual phenomenon that most likely occurs due to the fact that when you’re in total darkness, your eyes have nothing to anchor to—no reference point—which messes with your mind’s ability to keep that light in its spot in space. Specifically, as the IMAGE of the light moves on your retina (due to slight muscle movements of the eye), you perceive the actual light to have moved as well.

Though seemingly harmless, the autokinetic effect can be quite dangerous to airplane pilots flying at night. One of many fascinating aviation-related sensory illusions, autokinesis can alter a pilot’s ability to land the plane based on a set of guiding lights; it can also interfere with the act of flying in formation, refueling in the air, and a number of other maneuvers.

Autokinesis, unsurprisingly, is cited as the explanation for many UFO sightings.

You’re taking a shower, humming a tune, enjoying the feel of the warm water on your skin. The windows are closed and there is no circulation in the bathroom. Then, with no provocation, the shower curtain simply reaches out and sticks to you, wrapping around you with its clammy hands. You unstick it as best you can, but it persists.

So the question is: what’s going on? This is called the “shower curtain effect,” and like some of the other items on this list, it’s been studied but isn’t yet fully understood. There are several primary competing and overlapping theories:

(1) Buyoancy. As the hot shower air rises and replaces cold air, it loses density, causing a pressure imbalance that leads to the curtain moving inward. The issue with this theory is that the shower curtain effect happens with a cold shower as well.

(2) The Bernoulli effect. This one accounts for the change in air pressure by the fact that air matches the speed of the water shooting out of the shower head; in other words, as the water gains speed, the pressure drops. This effect is at the heart of how airplane wings create enough lift to fly.

(3) The horizontal vortex theory. Only studied with computer models, this theory states that the pressure imbalance is caused by a horizontal vortex stemming from the water spray.

Simply stated, the Sylvia Plath effect is a theory that seeks to explain the apparently disproportionate number of female poets to suffer from mental illness. More broadly, it is claimed that poets of either gender—and even more broadly than that, creative writers—succumb more easily to depression and other mental illness than other writers, as well as other celebrities. The link between creativity and mental illness has been suggested and studied for centuries—Aristotle wrote that creative writers and thinkers all tend to gravitate towards “melancholia.”

American psychologist James C. Kaufman, who has done extensive research on creativity, coined the term “Sylvia Plath Effect” in 2001 while researching the effects of creativity on mental illness. Numerous academics have performed studies, seeking to answer questions about the causes of mental illness, the chicken-and-egg nature of its relationship to creativity, the stigma surrounding depression, and much more. The connection between creativity and mental illness, especially a causal relationship, is still not clearly understood, and studies have raised more questions than they’ve answered. A few things, however, appear to be true—the connection between creative writers and mental illness is real, it affects poets more than other writers, and women more than men.

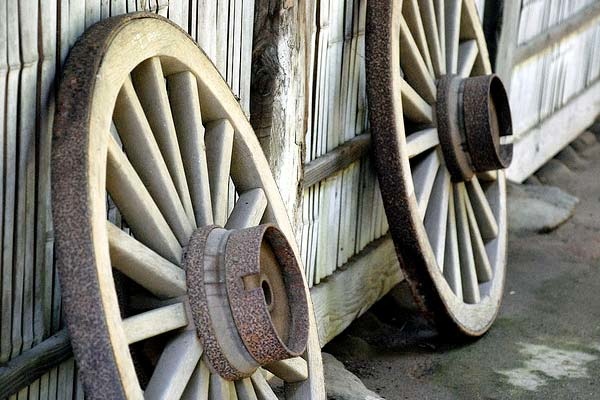

The wagon-wheel effect describes the optical illusion wherein spoked wheels seem to rotate differently than one might expect given the direction in which the vehicle is moving. The spoked wheels of a car driving by may appear to rotate more slowly than the wheel itself, may appear to stand still, or may even seem to rotate in the opposite direction. This effect is not fully understood, though a few competing theories exist.

When it happens on film—say you’re watching a movie with a car in it—the effect is fully explainable, and is related to the “stroboscopic” nature of film. Movies capture a rapid series of still images, usually 24 per second, so there is missing visual information—but our brains fill in that missing information in a logical way. When a car is traveling quickly, a wheel may go MOST of the way around in the space of one frame, and our minds perceive this as movement BACKWARDS. When this happens in real life, however, the explanation isn’t as clear-cut. One theory is that our minds actually process visual information as a series of “stills,” much like a movie; another proposes that two warring interpretations (within our brain) of a visually confusing scene result in the effect.