History

History  History

History  Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Desperate Last Stands That Ended in Victory

Animals

Animals Ten Times It Rained Animals (Yes, Animals)

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

10 Greatest Ancient Athletes

Like their modern-day counterparts, ancient athletes had a way of capturing the public’s imagination. Through ancient authors such as Pindar, Pausanias and Dio Chrysostom, we can still learn today about the incredible achievements of some of the best-known Olympic victors of ancient times. Although the modern sporting legends of today have no reason to be jealous of the ancient champions, the truth is that there are certain victories and records from the past that would make even the most decorated Olympians of the modern Olympics blush.

Despite the fact that the ancient sports and competitions were quite different from our modern professional sports, the ancient champions—just like those of today—were heroes among their people. Perhaps their greatest accomplishment of all is the fact that what they achieved is still remembered today; their names are still prominent in athletics, even two or three thousand years after their deaths.

Orsippus of Megara was an ancient Greek athlete who won the stadion race of the fifteenth Ancient Olympic Games in 720 B.C. He became the crowd’s favorite, and he was thought to be a great pioneer for being most likely the first ever athlete to run naked. Pausanias, who very often reported on the ancient Olympics like a modern-day sports journalist, states: “My own opinion is that at Olympia he [Orsippus] intentionally let the girdle slip off him, realizing that a naked man can run more easily than one girt.”

Varazdat was an athlete from Armenia who won the Olympic boxing tournament during the 291st Olympic Games. We are aware of Varazdat’s victory from a memorandum kept in the Olympic museum in Olympia. The first historiography about Varazdat was written by Movses Chorenatsy in his Armenian History.

In ancient Armenian royal and aristocratic families, the physical education of youngsters had a disciplined and orderly character. They were taught swimming, boxing, wrestling, weightlifting, and military exercises. Varazdat, with the benefit of this rigorous training, went on to be the winner of various boxing competitions held in Greece. He later achieved his greatest triumph, when he became the Olympic champion at the Olympics of 385.

Although men were originally the only ones allowed to compete in the Olympic Games, this soon changed. Several women took part in the ancient Games, and even won competitions. The most famous of these was Cynisca of Sparta, the first woman to win at the Games. By her success, she paved the way for many other women, and helped usher in a new era in the ancient sporting world.

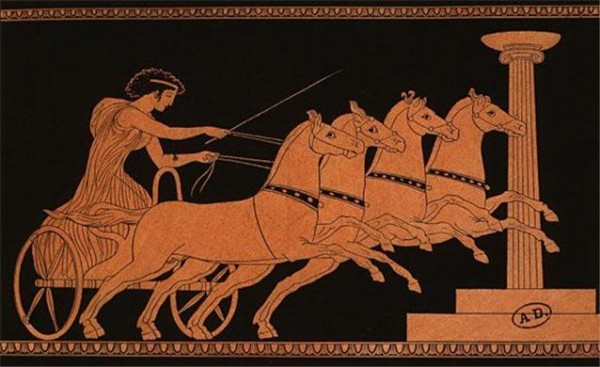

Cynisca’s and her male team were successful in the four-horse chariot racing, winning in 396 B.C. and again in 392 B.C. Cynisca was the most distinguished female athlete of the ancient world, and many historians use her as a symbol of the social rise of women, and the beginning of the movement to give them equal rights and opportunities.

We don’t know much about the Olympic victor Polydamas of Skotoussa. His background, family life, and even the details of his Olympic triumph remain shrouded in mystery. Aside from the fact that Polydamas’ statue was remarkably tall and strong, we have no other information on his appearance.

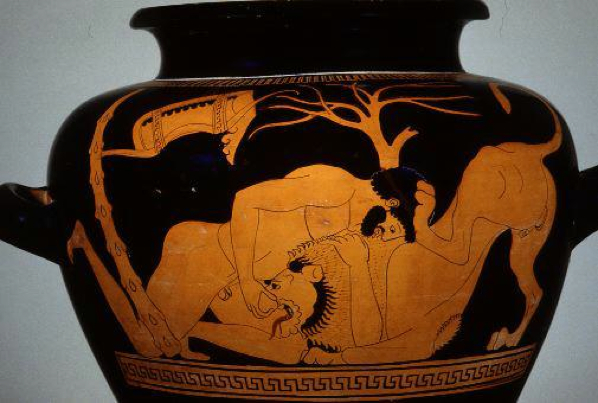

Like many athletes of his time, Polydamas was just as well-known for his non-athletic exploits as he was for his prowess in the Olympic games. Ancient authors tend to compare his feats to those of the legendary Greek hero Herakles. Polydamas once killed a lion with his bare hands on Mount Olympus, in a quest to imitate the labors of Herakles, who famously slew the Nemean lion. For similar reasons, Polydamas once managed to single-handedly bring a fast-moving chariot to a halt.

These exploits soon reached the ears of the Persians. Their king, Darius, sent for Polydamas. After he was received by the Persian king, the athlete challenged three Persian “Immortals” to fight him, and managed to defeat them all in a single fight.

In the end, however, Polydamas’ strength could not prevent his demise. One summer, Polydamas and his friends were resting in a cave when the roof began to crumble down upon them. Believing that his immense strength could prevent the cave-in, Polydamas held his hands up to the roof, trying to support it as the rocks crashed down around him. His friends fled the cave and reached safety, but the great wrestler was killed.

Onomastos of Smyrna was the first ever Olympic victor in boxing, at the twenty-third Olympiad in 688 B.C., when this sport was added. According to ancient historians, Onomastos was not only the first Olympic boxing champion, but wrote the rules of Ancient Greek boxing as well.

Onomastos also holds a record which remains remarkable even today. After hundreds of ancient and modern Olympiads, he’s still the boxer with the most Olympic boxing titles, with four victories to his name. Laslzo Papp, the world’s greatest amateur boxer of the twentieth century, came close to Onomastos’ record—but he stopped at three Olympic victories before becoming a professional boxer.

The famously handsome boxer Melankomas was from Caria, a region in modern-day Turkey. In an effort to prove his courage, Melankomas chose to compete in athletics, since this was the most honorable and most strenuous path open to him. Amazingly enough, Melankomas was undefeated throughout his career—yet he never once hit, or was hit by, an opponent.

His boxing style involved defending himself from the blows of the other boxer, and never attempting to strike the other man. Invariably, the opponent would grow frustrated and lose his composure. This unique style won Melankomas much admiration for his strength and endurance. He could apparently last through the whole day—even at the height of summer—and he would refuse to strike his opponents, even though he knew that by doing so he would quickly end the match and secure an easy victory for himself. In this manner he won the Olympic boxing tournament at the 207th Olympic games.

Chionis of Sparta was an athlete who caused much debate regarding his athletic achievements, with the most notable of these being his long-jumping records. Records suggest that in the Olympics of 656 B.C., Chionis jumped a record of seven meters and five centimeters. This feat would have won him the long jump title at the 1896 Olympic Games, and would have placed him among the top eight at a further ten modern Olympics, up to and including the 1952 Games of Helsinki. As well as his amazing achievements in long jump, Chionis was also renowned as a triple jumper—capable of reaching up to 15.85 meters.

Chionis of Sparta was an athlete who caused much debate regarding his athletic achievements, with the most notable of these being his long-jumping records. Records suggest that in the Olympics of 656 B.C., Chionis jumped a record of seven meters and five centimeters. This feat would have won him the long jump title at the 1896 Olympic Games, and would have placed him among the top eight at a further ten modern Olympics, up to and including the 1952 Games of Helsinki. As well as his amazing achievements in long jump, Chionis was also renowned as a triple jumper—capable of reaching up to 15.85 meters.

But the most remarkable fact about this man is that none of his jumps were enhanced by modern-day drugs or training equipment; his records were truly honest and honorable.

Diagoras of Rhodes might not be the greatest of ancient athletes, but his family is without doubt the greatest sporting family of the Ancient world. Diagoras won the boxing event in the Games of 464 B.C. He was also a four-time winner in the Isthmian Games, and a two-time winner in the games at Nemea.

Diagoras of Rhodes might not be the greatest of ancient athletes, but his family is without doubt the greatest sporting family of the Ancient world. Diagoras won the boxing event in the Games of 464 B.C. He was also a four-time winner in the Isthmian Games, and a two-time winner in the games at Nemea.

His sons and grandsons also became boxing and pankration champions. During the eighty-third Olympiad, his sons Damagetos and Akousilaos, after they became champions, lifted their father Diagoras on their shoulders to share their victory with him. Legend says that during Diagoras’ triumphant ovation on the shoulders of his sons, a spectator shouted: “Die, Diagoras, for Olympus you will not ascend”—the meaning being that he had reached the highest honor possible for a man and athlete.

Theagenes was one of the first celebrities of the ancient sporting world. He became famous throughout the world at the tender age of nine.

Theagenes was one of the first celebrities of the ancient sporting world. He became famous throughout the world at the tender age of nine.

It seems that the boy was walking home from school one day when he noticed a bronze statue of a god in the marketplace of Thasos, Greece. For some reason, Theagenes tore the statue from its base and took it home. This act outraged the citizens, who perceived it as blasphemy against the gods, and they debated whether or not they should execute the child for his deed. One elder, however, wisely suggested that they should have the boy return the statue to its proper place. Theagenes did this—and his life would never be the same again.

He went on to become one of the greatest athletes of all time. He was a successful boxer, pankratiast, and runner. He won the Olympic boxing tournament in the seventy-fifth Olympiad of 480 B.C., and in the next Olympics he won the title in the Pankration. In addition to his two Olympic victories, Theagenes won numerous honors in other sports and other games. Altogether he was said to have won over 1,400 contests in many different kinds of sport. His incredible achievements made him a living myth—to the extent that many people even believed that Heracles was his father.

If we were to compare Theagenes with a modern boxing hero, such as Harry Greb (the boxer with most official victories (261) in professional boxing’s history) it would seem that Theagenes outnumbers him by nearly 1,250 victories.

Most historians agree that Milo remains to this day the greatest wrestler and fighter (from any combat sport) the world has ever known. Milo of Croton became an Olympic champion several times during his nearly thirty-year career. His size and physique were intimidating, and his strength and technique perfect—and many people accordingly believed that he was the son of Zeus.

He was said to eat more than eight kilograms of meat every day. Some say that he even once carried an adult bull on his shoulders, all the way to the Olympic stadium, where he slaughtered and devoured it. Yet Milo was not merely a hulking wrestler; he was also a musician and a poet, as well as a student of the mathematician and philosopher Pythagoras.

The greatest wrestler of the twentieth century, Alexander Karelin, was often called the modern-day Milo of Croton—but he himself acknowledged that he would not stand a good chance against the real Milo.

Theodoros II is a budding author and a law graduate. He loves History, Sci-Fi culture, European politics, and exploring the worlds of hidden knowledge. His ideal trip in an ideal world would be to the lost city of Atlantis.