The Arts

The Arts  The Arts

The Arts  History

History History’s Ten Most Lopsided Battles Ever

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

The Arts

The Arts 10 Iconic Masterpieces Attacked by Pure Pettiness

History

History History’s Ten Most Lopsided Battles Ever

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

10 Terrifying Playwrights Of The 20th Century

Theatre can hit you hard and fast if you’re in the right mood. It is more immediate than film and television, it asks you to sympathize with the characters, no matter how cruel they can be, and it is never exactly the same each time you go. While musicals and comedies tend to do better at the box office, it takes a great artist to make the audience go home both satisfied and horrified. This is a list of some of the best and most twisted minds that the theatre presented us with in the last century. Definitely keep your eyes peeled for these names in your local theatre’s upcoming seasons.

The only reason that Strindberg lands so far away from number 1 is that most of his work was done in the 19th Century. But he lived in the 20th Century and he is one of a great many responsible for shaping and inspiring the playwrights listed below. I can’t think of one of his plays that could be described as a happy experience. He certainly wrote great experiences—but not happy ones. He wrote a realist manifesto in his introduction to Miss Julie then swiftly left it behind, moving into weirder and creepier forms represented brilliantly in his A Dream Play and Ghost Sonata later in his career. He was a self-absorbed misogynist, expressing his frustrations and mental-daemons sweepingly with his paintings, poetry and essays, as well as play scripts.

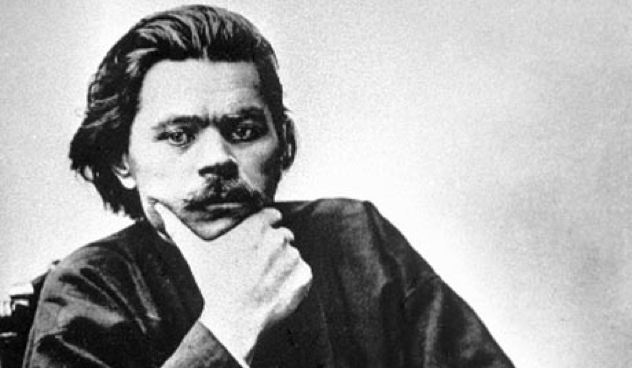

Straddling the 19th and 20th Centuries, Maxim Gorky jump-started his career with only the second play he ever wrote, aptly titled The Lower Depths. While pursuing a style of realistic theatre, Gorky wrote The Lower Depths with a greater focus on creating fascinating characters rather than a memorable plot. It is speculated that, while developing these characters, Gorky might have made regular visits to a local homeless shelter, offering booze in exchange for stories and time. First reception of this play was extremely negative, criticizing the bleak hopelessness and amoral content of the character’s lives. Despite these initial reviews, it is considered today as one of the cornerstones of Modern Theatre. Though The Lower Depths remains his most popular play; he went on to write fifteen more plays after, maintaining his taste for the ruthless examination of human struggle.

As of yet, Manjula Padmanabhan has only written five plays. Her most famous, Harvest, is a science fiction about an impoverished part of the world where people agree to let their bodies become available for harvest by wealthier Westerners who offer all kinds of luxuries in return. It’s a pretty clear metaphor for the globalized affects of capitalism on third-world workers. What Padmanabhan brilliantly does, however, is represent both ends of this equation in a single family in a small apartment in India. As the character Om spirals into fear inspired, in part, by the people who obsess over his health and control his life, his mother gradually sedates herself in the luxuries brought to her by his sacrifice. The person who owns Om, represented by weird holographic apparitions, believes herself to be generous and helpful to him. Through these, and other characters, the audience is forced to watch magnified versions of the different mercenary parts of themselves. Even Om ends up dishonest, ever the victim.

Brendan Behan makes this list for two reasons: the chilling content of his two most famous plays, and the short horrible life that he led. He was a member of the Irish Republican Army who, even after Irish home-rule, took it upon himself to visit Liverpool and blow-up strategic parts of their harbor. He was arrested, unsuccessful of his intentions. He spent three years in jail and later, not even yet twenty years of age, was arrested again for an assassination attempt. His most famous play, The Quare Fellow, is about a group of prisoners awaiting the execution of their fellow inmate. Behan presents the situation with humor and intensity. At the end of the play, the deceased is deceased and the characters are still coping with themselves behind bars. Behan killed himself with alcoholism. After the successes of The Quare Fellow, The Hostage, and his book The Borstal Boy, he continued to write but never as brilliantly or successfully. The diminishment of his craft was clearly a result of his drinking. “I’m a drinker with a writing problem,” he used to say, “There’s no bad publicity except an obituary.”

Though not all his works are particularly terrifying, this list would be amiss without the great Arthur Miller. He wrote over 50 stage and radio plays, spanning his active career over seven decades. His darker side comes across more subtly than other members of this list, drawing his audiences to examine their existential selves with the nuances of his story-telling rather than relying on gimmicks in form or spectacle. Plays like All My Sons and A View from the Bridge start in the recognizable workaday world and carry us expertly into haunting scenes of violence at the plays’ climaxes. Death of a Salesman hardly needs mention as the “great American tragedy;” a portrait of life’s futility, built almost artificially by the failing social system we all cling to. Miller wrote with Shakespearian grandeur of story, mingling the lives of ordinary people with the devastating realities of all the things bigger than us—God, philosophy, truth, and social structures. He made the most devastating familiar and the familiar to be devastating.

Even more prolific than Arthur Miller, Howard Barker invented an entire genre called “The Theatre of Catastrophe.” He takes inspiration from the most horrific of historical events and shows them to us openly and provocatively. By often writing characters that are imperfect or anti-heroic he invites his audiences to make their own judgments and fall into discourse among themselves. Philosophically Barker is noted for his rejection of Realism’s goal to evoke a common reaction from a crowd; we all take what we take from a play and the experienced truth lies across a spectrum. In terms of content, however, Barker is not shy of harrowing circumstances and exacting images: he takes advantage of his character’s trust in the world, describes the smell of battlefields, makes old flesh wounds into important character traits, he even pours a wave of horse blood across a huddled group of desperate workers.

Sartre is so iconic of existential thought and art that, in 1948, the Catholic Church attempted to ban his books entirely. He was an academic who, before his experience as a soldier in the Second World War, professed a sort of rationalism: the utility of one’s actions makes their existence acceptable. The war shook Sartre deeper into this self-floundering direction and he came out even more existentially tormented (if you can imagine it). His most famous play, Huis Clos (No Exit, in English), puts the three most terribly matched people in the same room for all of afterlife so that they can torment each other as they watch their loved-ones slowly forget them on earth. All of Sartre’s creative writing is extremely symbolic and bleak in style, expertly reserving language as necessary to convey his sadistic messages.

Known for some of the longest play titles in history, Peter Weiss’s style and subjects of interest are pretty hard to miss at face value: The Persecution and Assassination of John-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade is one example, or how about Discourse on the Progress of the Prolonged War of Liberation in Viet Nam and the Events Leading up to it as Illustration of the Necessity for Armed Resistance against Oppression and on the Attempts of the United States of America to Destroy the Foundations of Revolution as another example? His plays are clearly at once specific and sweeping in subject. Often inspired by the power abuses of military formality, Weiss uses metatheatrical conventions to push the audience emotionally in and out of his stories. His writing is capable of making an audience feel simultaneously triumphant and disgusted by the curtain-fall, forcing, in turn, a deeper consideration of what we think about ourselves.

Along with Arthur Miller, Beckett is one of the most celebrated playwrights of the 20th Century. He was a master of combining imagery with timing in order to build the most bitingly visceral productions possible. Best known for Waiting for Godot as a landmark for theatrical surrealism, Beckett’s work burrows significantly deeper in that direction with some of his shorter plays. Despite this he resented being given labels such as surrealist, expressionist, or even minimalist … though even he couldn’t deny his minimalist aspirations. Arguably his best play, Endgame, opens with a lone man on a nearly empty stage, sitting ghostly still under a tea cloth. The play is set at the end of the world where the characters are locked in a house, enduring the final stages of their painful existence. His work is incomparable to other playwright’s, beautiful to see, beautiful to hear and, when well produced, can be literally staggering to experience.

Sarah Kane only wrote six plays before her death in 1999, moving from realistic stories of intense violence to more poetic and experimental pieces nearer the end of her career. She is a pioneer of the British literary movement, “In-Yer-Face-Theatre,” attacking her audiences with the cruel and obscene. Probably because of the grotesque pushiness of her plays, they were not well received by her own community during her lifetime. She has, however, had pieces played for large audiences in Mainland Europe and very successfully revived in the Americas. Her writing is violent in content and affect, shocking her audiences with the darkest possibilities of human action; Kane wrote about sex, pain, torture, death, racism, and rape. She was a brilliant wordsmith, building poetry with the slightest necessity of language, but certainly not a playwright for the more sensitive theatergoers.