Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Greatest Impostors Of The 20th Century

For some reason, the world is enthralled with the idea of the impostor. They’re sneaky, deceitful, and devoid of morals—but dang it, they do it with style. For example, one of the most famous impostors in recent history is Frank Abagnale, inspiration for the Spielberg/DiCaprio film Catch Me If You Can. He robbed, cheated, and lied his way into a fortune, but no matter how many checks he forged, you just can’t help rooting for the guy.

In the past we’ve talked about some of the greatest impostors in history, but here’s another installment for your viewing pleasure. These are 10 of the greatest impostors and con men of the 20th century.

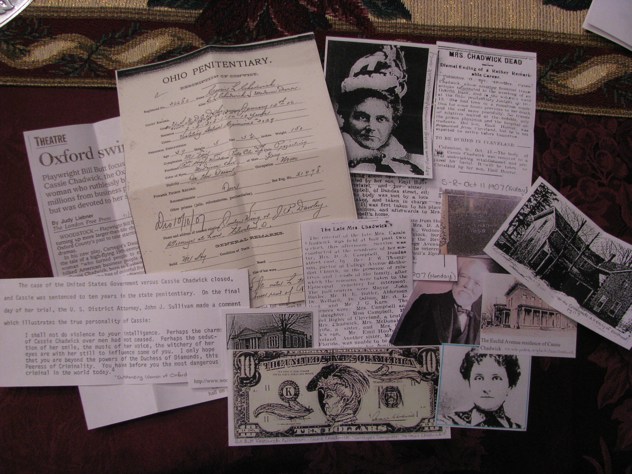

Our first entry begins in the final years of the 1800’s and carries over to the leading decade of the 20th century. Cassie Chadwick was born Elizabeth Bigsley in 1857, and it wasn’t long before she embarked on a long and incredibly successful con career. It only took fourteen years to lead to her first arrest—she was picked up after forging checks in Ontario under the claim they they were inherited from a long lost British uncle. The court released her shortly, claiming her to be insane—a dubious accomplishment for a 14-year-old.

As the years progressed, so did Cassie’s schemes. In 1882 she married her first husband, masquerading as a clairvoyant named Madame Lydia DeVere. The high profile wedding, however, brought her past victims out of the woodwork and to her front door, demanding payment for the money she had stolen from them. The marriage lasted less than a year.

Fifteen years and three husbands later, Cassie Chadwick embarked on her most ambitious scam to date, and the one that turned her into a legend—she convinced the world that she was an illegitimate daughter of Andrew Carnegie, the ludicrously wealthy steel and railroad mogul. Over the next eight years, she scammed up to $20 million in bank loans under Carnegie’s name—while the banks themselves were too afraid to ask Carnegie to vouch for the loans for fear of stirring up controversy over his “illegitimate daughter.” The entire scheme collapsed around her in 1904 when she was arrested after one bank called her bluff. She was given 14 years in jail, but in 1907 she died due to heart complications.

It’s hard to fault a man for trying, no matter how devious their intentions may be. And it’s hard to find a man who tried harder than Stanley Clifford Weyman. Unlike most impostors, Weyman wasn’t in it for the money—he wanted the adventure, famously stating: “One man’s life is a boring thing. I lived many lives. I’m never bored.”

In between impersonating navy and military officials, journalists, and the actual U.S. Secretary of State, he also masterminded a meeting between an Afghani princess and Warren Harding, the President of the U.S. See, in 1921, Afghanistan and Britain were in talks to negotiate a peace treaty, and Princess Fatima, of Afghanistan, was visiting the U.S. However, the U.S. government wasn’t acknowledging her official presence.

So what did Weyman do? He visited Princess Fatima under the guise of a Liaison Officer for the State Department and promised that he would arrange a meeting between her and President Harding. All he asked was that she supply $10,000 as a complimentary present to the State Department. But here, where most con men would have taken the money and run, Weyman actually followed through on his promise—he used the $10,000 for first class transport and accommodations for the princess, then lied his way up through the chain of command at the White House until he got to the president himself. When the press released his photo beside the princess and the president, he was recognized and arrested. Why did he do it? Just to see if he could.

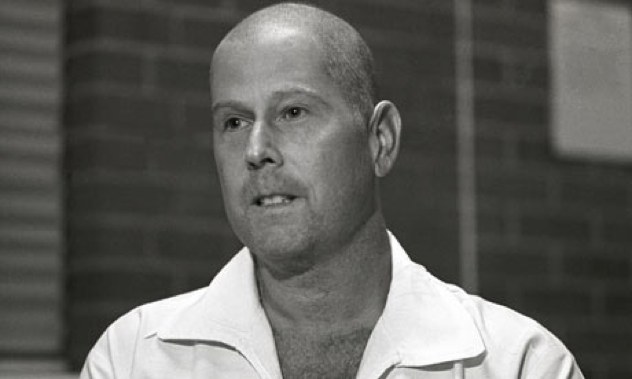

It’s rare that an impersonator will manage to make a positive impact on the world and save the lives of the people who come to depend on him. Most impostors are after money or, in the case of Stanley Weyman, excitement. For Ferdinand Demara, impersonation was about filling in gaps, picking up the pieces where a job was needed, whether he had the training for it or not.

Early in his “career,” Demara was a soldier in the military. Not happy with where that was taking him, he decided to fake his own suicide in 1942 and assumed the name of Robert French, then began teaching college psychology at a Pennsylvania university. Every now and then he would move to a different university position under a variety of names. Eventually, though, he was caught and given jail time—not for impersonating anyone, but for deserting the army years earlier.

Out of jail and with the headlines of the Korean War plastered across newspapers, Demara decided to assume the name of an acquaintance, a surgeon named Joseph Cyr. Under his new identity he got a job on the Canadian destroyer HMCS Cayuga and shipped off to Korea. Unfortunately, he turned out to be the only surgeon on the ship, and ended up performing more than sixteen major surgeries—with no formal training. All of his patients recovered. In the biography of Demara’s life, The Great Impostor, Demara claimed that he simply read a surgery textbook before operating.

George Dupre is an interesting case, in that his only real impersonation was of himself. However, the history he actually had and the history he claimed to have were so different that he inadvertently became one of the greatest Canadian war heroes in the years following WWII.

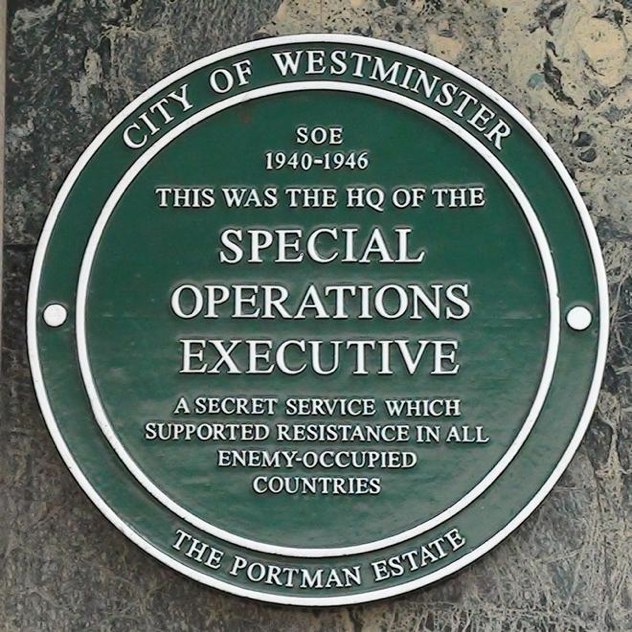

After the war ended, Dupre began traveling across Canada as a public speaker, describing his missions as a spy for the Special Operations Executive, a legendary espionage organization sometimes referred to as the Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare. Dupre wove intricate tales of life behind enemy lines in occupied Paris, working with the underground resistance to overthrow the Nazi Gestapo. He described his harrowing experience as a prisoner of the Gestapo undergoing weeks of physical and psychological torture yet refusing to divulge any information. His story became so widespread that a book was written about it, The Man Who Wouldn’t Talk, and Dupre became an international sensation.

Except that none of it ever happened. With the fame from the book came testimonies from people who had actually served with Dupre in the war. The truth was, Dupre spent the entire war behind a desk in London. It turned out that Dupre had just embellished a few stories for fun, and somehow the entire thing spiraled out of control. Aside from the fame though, Dupre never benefited from the book deal and the public talks—he donated all his proceeds to Scouts Canada. His biography was reclassified as fiction.

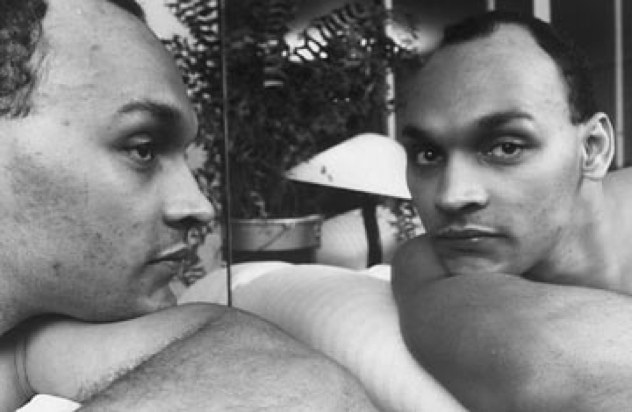

Most of the impostors on this list got their start at a young age—few of them achieved notoriety before the age of twenty. David Hampton is now considered one of the youngest successful con artists and impersonators, and his story has since been adapted into the play and film Six Degrees of Separation. His gimmick: impersonating actor Sidney Poitier’s son (Sidney Poitier actually has six daughters and zero sons).

In 1983, at the age of nineteen, David Hampton tried to get into a Manhattan night club with a friend. The bouncers refused to let them in, but when Hampton came back later and told them he was Sidney Poitier’s son, they immediately showed him to the VIP section. Thus, an identity was born. Hammond took to showing up at first class restaurants, claiming that he was meeting his “father.” He would dine, then act disappointed when his father never arrived while simultaneously signing the check in Poitier’s name.

Soon he began to target the wealthy citizens of Manhattan—including Calvin Klein and Gary Sinise, among others. Hampton would introduce himself as David Poitier, then make up a story about how he had been mugged and needed a place to stay until his father arrived the next day. In one of these homes he stole an address book, and took to calling first, claiming that he was a friend of their son/daughter from college.

After Hampton’s story became famous in Six Degrees in 1990, he began traveling the country under various other personas (“David Poitier” wouldn’t exactly fly anymore), playing the impersonation game until 1993, when he passed away from AIDS.

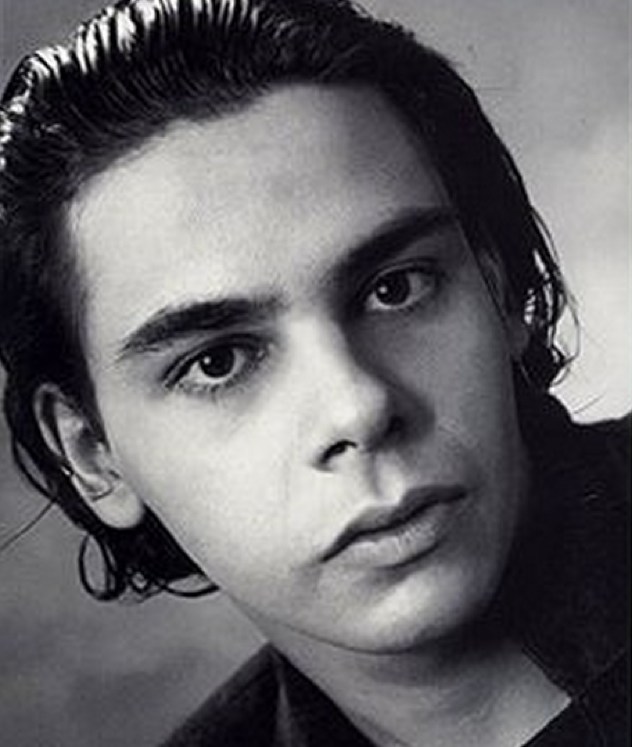

Christian Gerhartsreiter is a German who moved to the U.S. in 1979 in the hopes of getting a job as an actor. His plan worked—but not exactly in the normal sense. A mere eighteen years old with no money, no connections, and no legal visa to be in the States, he decided that the best thing to do would be to get married and obtain a green card through his wife. So that’s what he did—he found a young woman named Amy Duhnke and told her that if he were sent back to Germany he’d be conscripted into the German army to fight the Russians (this was during the Cold War). She agreed to marry him, but the day after the wedding Christian skipped out on the honeymoon and pointed his compass towards California, where his true calling lay.

His true calling, of course, was to become Clark Rockefeller—the faux multimillionaire social butterfly who spent the next two decades—from around 1985 to 2006—claiming to be a member of the illustrious Rockefeller family. The plan worked exceedingly well until his wife Sandra Boss (of 11 years we should add), began to get suspicious that he was not, in fact, a Rockefeller. The married couple had been living exclusively on Sandra’s income the entire time, while “Clark” pursued high profile social connections.

And the rest, as they say, is history. Sandra Boss discovered the lie, filed for divorce in 2006, and left with their daughter. Two years later, Clark was arrested for kidnapping his daughter in Boston, sparking a whirlwind investigation into this mysterious German’s true identity. As it turned out, he also killed a guy.

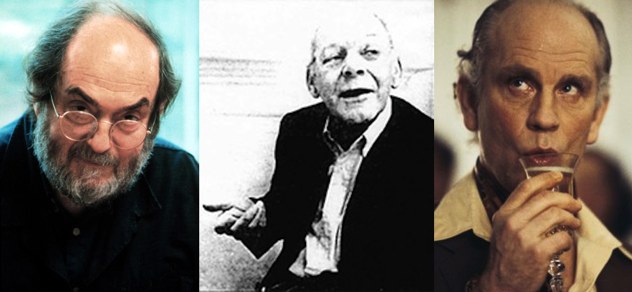

Stanley Kubrick is an American director who’s something of a legend among movie buffs. The words “greatest director in history” have been thrown around, along with the words “not British” and “heavily bearded.” Those last two are particularly important, because in the early 90’s the reclusive Kubrick began to show up in social clubs in London—only now, he was clean shaven and decidedly English. The “new” Kubrick was actually a man named Alan Conway, who had taken to using the name for the social status it imparted.

Despite the changes in his physical appearance, and reportedly having next to no knowledge of any of Kubrick’s films, Alan Conway (real name Eddie Alan Jablowsky) managed to keep the charade going. Since the real Kubrick hadn’t been seen in public more than a handful of times in the past 15 years, it couldn’t have been terribly difficult—and even people who had actually met Kubrick in real life were fooled by the act. The film critic Frank Rich was famously convinced and, based on Conway’s behavior, came to the conclusion that Kubrick was gay (which Conway was).

Unfortunately, this story would be hilarious if it wasn’t quite so tragic. Conway was a violent alcoholic, according to his son, and his impersonations were closer to fanatical delusions than any carefully calculated plan. Conway passed away in 1998 from heart problems.

In the past, masquerading as one of the captains of industry seemed to be the surest way to a quick million. These days, the Hollywood faces are the new American royalty. In 1992, Tehran native Anoushirvan Fakhran came to the States on a student visa, and spent the next several years living a lavish lifestyle, sprinkled with privileges usually reserved for celebrities and visiting royalty. That’s because nobody knew him by the name of Anoushirvan—to everyone who knew him, he was Jonathan Taylor Spielberg, nephew of director Stephen Spielberg.

In fact, he had even gone so far as to officially change his name to Spielberg in 1997. Then, in 1998, an anonymous woman placed a call to Paul VI high school in Fairfax, Virginia. She claimed to represent Steven Spielberg, and said that his nephew would be filming a movie in the area and wanted to research high school life. So the school allowed “Jonathan” to attend free of tuition, and gave him an official transfer from his previous school, the fictitious Beverly Hills Private School for Actors. Jonathan Spielberg was now a student.

During this time, Jonathan and his mother were living in a posh apartment in Fairfax Village, and Jonathan drove a BMW to school, often parking in the school principal’s reserved space. Nobody complained; he was related to a celebrity. Eventually though, the scheme backfired—Jonathan stopped attending classes, and the school tried to reach Steven Spielberg to find out why. Jonathan was arrested and sentenced to 11 months in jail for forging documents.

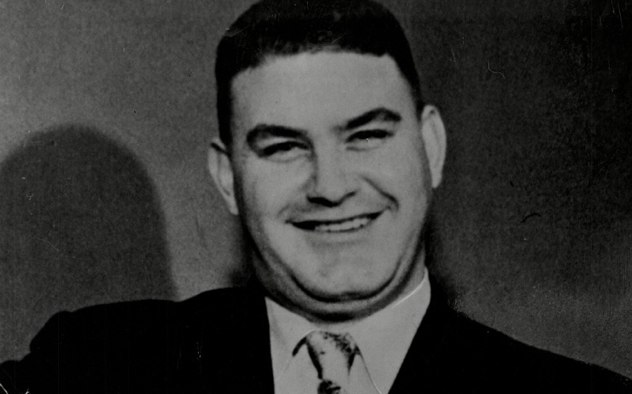

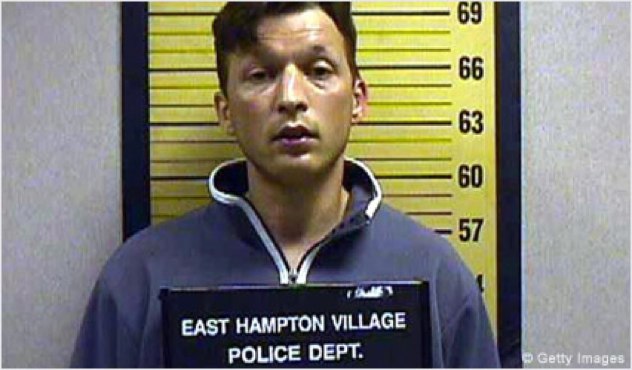

Steven Russell is probably closer to an escape artist than an impostor, but the means through which he masterminded his many prison escapes are the stuff of legend. In 1990, Russell lost his job and, instead of searching for new work, faked an accident and sued the company. This landed him his first prison sentence, and his first chance to escape. In 1992, Russell impersonated a prison guard by changing his clothes and just walking right out of the prison.

On his second arrest, which was for embezzling nearly $1 million from a medical company, Russell was given a $950,000 bail—he couldn’t pay it, so he simply called the courthouse, told them he was a judge, and reduced the bail to $45,000, which he promptly paid. Unfortunately, he was quickly tracked down again once the error was discovered, and Russell found himself facing a 40 year sentence for the previous embezzlement charges.

So he escaped again—this time by coloring his prison uniform with several dozen green markers until it resembled surgical scrubs. Again, he walked right out the front door. And again, he was quickly found and arrested. So this time Russell typed up fake medical records on a typewriter in his cell, and, through judicious use of laxatives, convinced the prison guards he was dying of AIDS. Then he called the prison and said that he was a doctor looking for volunteers to test a new AIDS treatment. When the prison warden announced the news, Russell promptly volunteered.

The next time he was caught, he faked a heart attack and was taken to a hospital under guard of FBI agents. So he asked to use the phone—and called the very agents guarding him under the guise of an FBI detective to let them know that they no longer needed to guard him. Russell is currently back in prison, looking forward to his release date in the year 2140. The film I love you Phillip Morris is based on his exploits.

The Rockefellers just can’t catch a break. Before the German Clark Rockefeller, there was Christophe Rocancourt, the “French Rockefeller.” Christophe started his scams big, and kept the ball rolling his entire career—his first scam was faking a property deed in Paris, and then selling that deed for $1.4 million.

With his wallet freshly stuffed, he then hopped the ocean to the United States and began fraternizing with the Hollywood fat cats, claiming to be a French relative of the Rockefellers. Through this alias (and others), he convinced multiple people to fund his fictitious projects. Most of the time, he never even had to make any concrete claims—he would just show up at a party and make a vague mention of his mother, who might happen to be an actress one week, or a famous producer the next week.

In 2006, he was interviewed by Dateline, and claimed that he had, all said and done, scammed about $40 million in his lifetime. His modus operandi was to convince someone wealthy that he was working on a large investment, but needed some capital to get it off the ground. The person would give Rocancourt the money, and Rocancourt would disappear. He famously convinced Jean Claude Van Damme, the action star, to produce a movie of his.

He was arrested for fraud in 1998, but has continued his scams well into the 21st century. As of 2009 he was in jail in Vancouver, where he told reporters, “I never steal. Never. I lied, but I never stole.”