Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Our World

Our World 10 Science Facts That Will Change How You Look at the World

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Incredible Female Comic Book Artists

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

10 Reasons Humans Are Naturally Evil

Take a cursory glance at the news headlines for any random day, and it’s not hard to develop a pessimistic attitude towards your fellow man. The endless reports of thieves, bombers, murderers, bigots, racists, and bullies is enough to make you lose all hope humans are capable of one day living in complete peace and harmony. Are we genetically predisposed towards “evil” behaviors like selfishness, violence, and cruelty? Or, is it an unfortunate side effect of our society? Not even those who make a living studying human behavior (psychologists, anthropologists, etc.) can come to a consensus on our inherent nature, but here are 10 facts that suggest we’re naturally a bit more naughty than nice.

In 2012, author and Harvard professor Steven Pinker wrote a book explaining that, contrary to popular belief, modern people are much less violent than their ancestors. Among other things, he cites the decline in murder rates, a drop in capital punishment, and lower war deaths (proportionally speaking). However, others call the 20th Century the bloodiest, cruelest time in history, fraught with endless wars and unprecedented cases of genocide. According to the Polynational War Memorial there were an astounding 237 wars between 1900 and today, starting with the Boxer Rebellion and continuing to the current war in Afghanistan. So, even if Pinker is right and things are better than they used to be, we still have a craving for war that we just can’t shake.

After watching any of the military training documentaries on the Discovery Channel, it indeed appears like some men were born for battle. They absolutely thrive under the high-pressure, aggression-filled environment of war. Not to mention, they really, really like their weapons. It makes you wonder what these men would do if there was no need to fight—could they even survive a desk job?

Essentially, the question boils down to—are we warring because we have to or because deep down we like it?

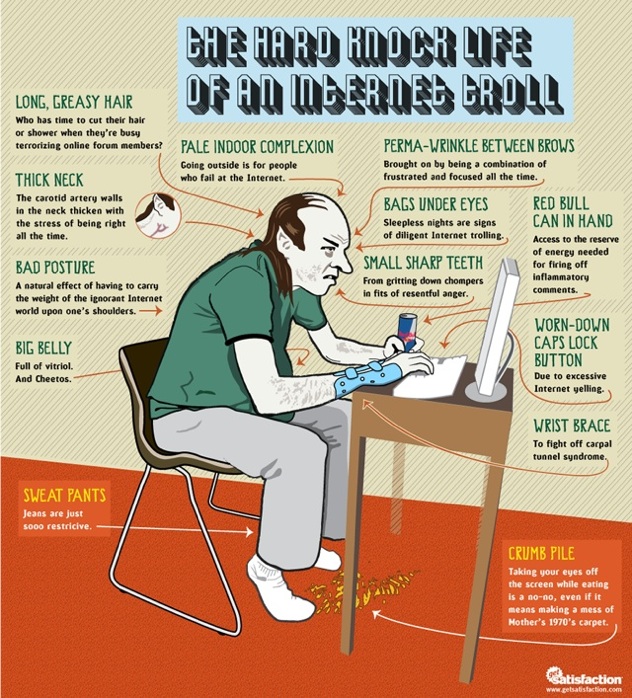

It doesn’t take much online exposure to realize people on the internet are inexplicably mean. Skim through any comment board on any site to see some of the most hate-spewed, dialogue around. What’s weirder is it’s usually unprovoked and over inconsequential stuff that logically shouldn’t trigger so much vehemence. You can’t even post a picture of a cute puppy without someone calling you a douchebag or saying only brainless liberals/republicans post pictures of puppies.

So, what gives? Why are people so stinkin’ mean online?

Many say it has to do with anonymity, which allows us to say things without fear of getting punched in the face. Others theorize many folks have a lot of pent up anger and the internet is a “safe” place to unleash it, and Scientific America claims it’s a result of lack of eye contact. Regardless of how we get away with it or why we do it, it’s evident that in unbridled, anonymous situations many people resort to cruelty.

If we want to analyze this issue from a genetic point of view, it makes sense to look at our closest living animal relatives for some insight. Unfortunately, this kind of complicates the matter since we are equally related (share 99% DNA) to both chimpanzees and bonobos, and while chimps have a propensity for violence, bonobos follow more of a ‘make love not war’ philosophy (literally). So, what kind of ape are we? Dr. Christopher Ryan, author of Sex at Dawn, tends to think we have more in common with bonobos and would be happiest in a non-competitive, sexually open society.

However, when you watch footage like the violent chimpanzee attack shown in Planet Earth, it’s easy to see the similarities between an organized chimp ambush and our own guerrilla warfare practices. In some cases, the chimps will cannibalize their victims—and any regular reader of Listverse knows humans have their own history with cannibalism.

Some argue we might be more relaxed and free lovin’ too if, like bonobos, we evolved in an environment where we didn’t have to compete for food. Still, we have to consider that today there’s plenty of food to go around if we were all willing to share, yet we continue to fight for resources and power as if it’s a lot more fun than making sure everyone has what they need. That being said, we all know humans are capable of living peaceably and, as scientist Dr. Christopher Boehm points out, it wasn’t until the emergence of human hunter-gatherers that primates started resolving conflicts through truces, trades, and peace pacts. So, while we all have the genetics for peace, it’s unclear whether it’s stronger than our penchant for violence?

Many of us have a romanticized perception of hunter gatherers, envisioning them as “noble savages” spending most of their days picking berries, hanging out by the fire, and having no concept of jealousy or personal property. There’s a common notion that if it wasn’t for agriculture and industrialization we’d all be stress free and hanging out in hammocks too. Of course, while it is true that hunter gatherers needed an extreme amount of cooperation and sharing to survive, their communal lifestyle didn’t mean there was never bloodshed.

For instance, things aren’t all smiles and rainbows (from a social perspective) in the few remaining hunter gatherer societies left in the world. The Sentinelese people in the Bay of Bengal, for example, have welcomed any would-be visitors to their island with a barrage of arrows and spears. In an incident in 2006, a couple of inebriated fisherman accidentally drifted too close to the island and were promptly killed and buried by the inhabitants. All outside attempts to recover the bodies proved too dangerous, so the island remains the men’s final resting place.

The Sentinelese aren’t the only ones who prefer fighting over negotiation. Anthropologists say two-thirds of modern hunter-gatherers are in a state of nearly constant tribal warfare, and 90% go to war once a year where they lose about 0.5% of their population. What’s worse is their high homicide rate, which results in the deaths of 25-30% of adult males.

Thus, it appears our modern lifestyle isn’t to blame for our violent tendencies, since people who have clearly avoided the industrial and technological revolutions are just as brutal as the rest of us (possibly more so).

The most convincing evidence that at least some of us are inherently violent is the existence of the so called “warrior gene.” This gene is technically known as monoamine oxidase A (MAOA), and while everyone has it, in a certain percentage of the population this gene exhibits low or no activity. Interestingly, those who have a low-performing MAOA gene are more prone to aggression and violent behavior—hence, the name “warrior gene.”

Just having the gene doesn’t guarantee you’ll be a violent person, yet it does mean you are predisposed towards aggression and impulsive decisions. Researchers have found those who have both troubled upbringings and the warrior gene are most likely to act out negatively. For instance, in a 2009 murder trial, a man was facing the death penalty for sadistically carving up and murdering his wife and her friend. The lawyer cited the warrior gene and an abusive childhood as the man’s defense, and apparently the man’s bad luck in both the nature and nurture departments convinced the jury to give him 32 years in prison instead of death.

It turns out, around one-third of people in the Western world have the warrior gene, and it’s present in as much as two-thirds of people in other, especially tribal, populations. Incidentally, women are less likely to have the gene since women have two copies of the X chromosome (where MAOA is carried), and it’s suspected the availability of two MAOAs would counteract any deficiency.

In some ways we aren’t much different than the ancient Romans with their gladiator games and fascination with blood and gore. For instance, prime time TV is full of shoot em’ up cop shows and gruesome crime scenes, most news agencies stick with the ‘if it bleeds, it leads’ philosophy, and one of the most violent sports in existence, mixed martial arts fighting, has been dubbed the fastest growing sport in the world. Without a doubt, we have a definite attraction to violence.

While most of the research regarding violence in entertainment has to do with how viewing it affects our behavior, perhaps the bigger question is why we like watching it in the first place? Maybe we’re drawn to it as a way to vicariously live out our savage instincts, or possibly we’re not so much attracted to the violence as we are the excitement. Some scientists argue our humdrum, civilized lives lack sensation and the thrill of conflict and danger provides a type of escape. The only problem with that theory is it doesn’t explain why native people also have ritual violence—unless it breaks up the monotony of their days too.

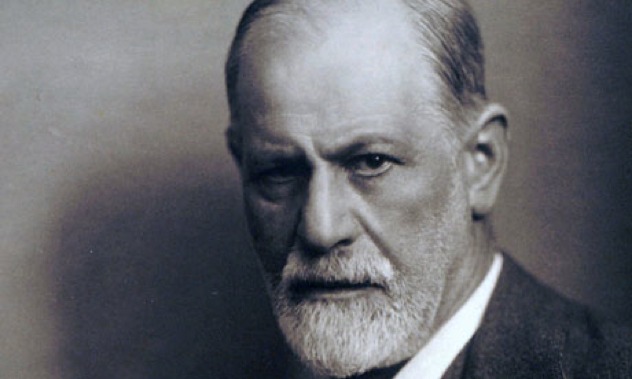

Towards the end of his life, Freud became largely disenchanted with the human species and considered us one of the worst types of animals. Granted, a lot of his feelings were based on the tumultuous time period in which he lived, as he witnessed World War I and died just as another major war, World War II, was getting started.

In his 1930 book, Civilizations and its Discontents, he wrote “…men are not gentle creatures, who want to be loved, who at the most can defend themselves if they are attacked; they are, on the contrary, creatures among whose instinctual endowments is to be reckoned a powerful share of aggressiveness.”

Hundreds of years before Freud, philosopher Thomas Hobbes had a similarly pessimistic view of humanity and famously wrote that the life of man in his natural state is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Essentially, he believed all men were equally capable of killing, and when two people want the same thing the inevitable outcome is war. In his mind, government and civil society were the only ways to curb the brutishness, yet he admitted even governments and the elite were full of corruption.

So, if we ignore Freud and Hobbes for the moment and assume other thinkers are correct, like Jean Jacques Rousseau who thought humans were naturally good or John Locke who believed we all started as a blank slate. Then it makes sense to presume babies—people who have been influenced the least by the world—would lean towards goodness or neutrality. But, is that really the case?

It’s difficult to say because, if you’ve spent any time with a toddler, you know at one point in the day he might be smashing his brother on the head with a wooden block and then five minutes later he’s generously offering you the soggy portion of his half-eaten cookie. Also, we have to teach them how to behave in a socially acceptable manner (i.e. don’t hit, bite, steal, and always, always share). If humans are naturally good, why do we have to spend so much time teaching children how to behave?

Despite all the social instruction that goes on during people’s formative years, researcher Arber Tasimi at Yale University believes his studies prove babies are naturally altruistic. The majority of his tests involve putting toddlers in various situations where they can choose to be selfish or helpful without reward. Surprisingly, in many instances the toddlers went out of their way to help others even when it was inconvenient and offered no incentive.

Regrettably, Tasimi’s theories go out the window when a mere cracker enters the equation. Yes, the toddlers in the study would quickly side with a “bad guy” or be unhelpful if it meant getting three graham crackers as opposed to one. Evidently, like most adults, children can be convinced to do wrong if the price is high enough.

The simple fact that we have any type of government suggests we believe society would spiral into absolute mayhem if there wasn’t someone making and enforcing laws. Essentially, we have very little trust in our fellow man to not kill or steal from us, so we willingly give up many of our own personal freedoms for the sake of protection. This in itself is pretty strong evidence that we believe a large portion of people aren’t innately good.

But would pandemonium actually ensue if we abolished government and lived in an anarchist state? It’s hard to say since hardly any major anarchist groups have existed throughout history—and perhaps that’s proof enough they don’t work. Even most hunter gatherer and tribal people, like the Australian Aborigines, rely on a group of elders to guide their community.

However, there was at least one significant anarchist society in history, which existed in the Ukraine between 1918 and 1921. It was named the Free Territory and consisted of around 7 million people who lived and worked communally to meet their collective needs. Still, even the Free Territory ended up having a leader of sorts in Nestor Makhno who served as the group’s main military strategist and advisor during the Ukrainian Revolution battles. In the end, the Bolsheviks branded the Free Territory as a warlord regime and forcibly overtook their land. Who knows what would have happened if this Ukrainian enclave was left to its own devices for the long term.

Apparently, our instinct to stay alive and compete for resources starts early… really early. Recently, high-clarity MRIs have shown twins fighting for space in the womb by kicking and pushing their sibling out of the way. Doctors initially planned to use the MRIs to study a different “selfish” condition, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, where one identical twin siphons blood away from the other. If stealing blood wasn’t bad enough, in cases of vanishing twin syndrome, a fetus will absorb their weaker uterine companion until it miscarries or simply “vanishes”—a legitimate survival of the fittest situation.

In truth, the twin who’s making off with the extra blood or nutrients isn’t consciously choosing to “steal” from his womb-mate, yet it’s interesting to see how even as fetuses we have to properly balance the available resources if everyone is to survive.

When it comes down to it, all our seemingly violent or egocentric impulses may be ingrained survival instincts. In other words, we’ll do what’s necessary to stay alive and make conditions more comfortable for ourselves. In our modern world some of these self-centered instincts are likely unnecessary, yet it’s quite a challenge to suppress millions of years of evolution.

S.Grant created this list in the spirit of debate and doesn’t really think all humans are evil, as there are just as many examples of true altruism (perhaps a topic for another list). Contact S.Grant here.