Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Incredibly Strange Cephalopods

With boneless bodies, serpentine arms, razor sharp beaks and bulging eyeballs, squids, octopuses and other cephalopods are seen by many as the most fantastic, otherworldly creatures in nature, tantalizing the human imagination from ancient legend to modern sci-fi horror, but even these tentacled blobs can adopt still stranger forms and habits. These are only some of the most divergent and unusual members of an already outlandish taxonomic class.

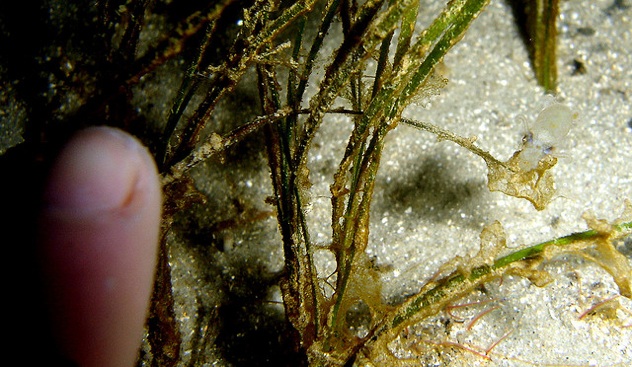

We all know that squid include the world’s largest and fiercest of invertebrates, living sea monsters who inspired terrifying nautical legends for centuries, but rarely do people talk about the world’s tiniest squid, Idiosepius notoides. Less than an inch long, they live exclusively among blades of sea grass, flitting between them like insects in an aquatic meadow.

Patches of sticky cells along a pygmy squid’s back allow them to stick themselves firmly onto grass blades when they need to rest, which leaves their tentacles free and keeps them from getting swept away when the currents get rough. They attach their eggs to grass blades in a similar fashion, a single row at a time, with the female guarding them closely until they hatch.

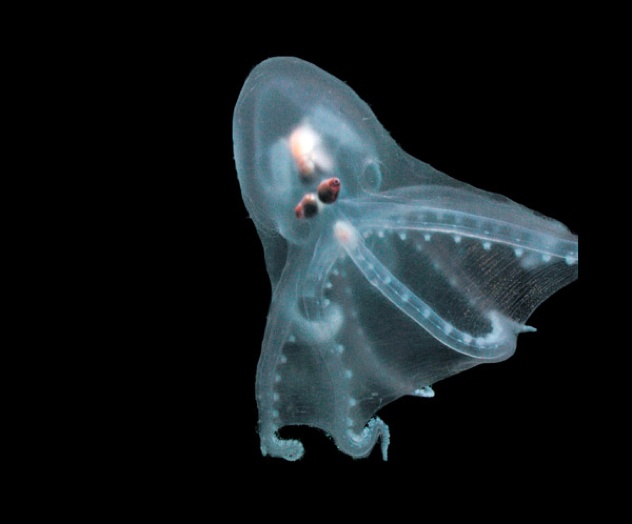

The closest thing in nature to a sheet ghost, little is known of these strange deep-sea cephalopods, closely related to the similar “dumbo octopuses” but classified in their own group, Opisthoteuthis, and distinguished by their smoother, saucer-like shape. We don’t know how they reproduce or even exactly what they eat, but they spend much of their time hovering or crawling along the sludgy bottom of the abyss, flattened into almost perfect puddles.

Cranchid or “glass” squid are a deep sea family distinguished by their completely transparent bodies, excellent camouflage for a life in the open water at perpetually dark depths. Some species additionally protect themselves by inflating like a balloon, swelling up into un-swallowable spheres. It’s the same tactic that blowfish are famous for, and it’s not all they have in common; some species, like this Cranchia scabra, are also covered in sharp, nasty tooth-like protrusions. They may also pull their entire head and all of their tentacles inside of their body, the squid equivalent of a turtle.

Another transparent deep-sea dweller, Amphitretus pelagicus is the only known species in its peculiar genus, distinguished by tubular eyeballs unlike those of any other cephalopod. These eye-stalks are able to rotate independently, much like a chameleon, and their sophisticated structure implies exceptional vision even among cephalopods, whose eyes are already superior to our own. All this may be due to the animal’s more squid-like lifestyle; always drifting in the open water, it has never been observed crawling on the sea floor like other octopus species.

Octopoteuthis deletron seems somewhat typical of deep sea squid at first glance, but has recently demonstrated a unique and rather morbid defensive mechanism; when attacked, it can detach and release one or more of its hook-lined arms, which will reflexively wrap around whatever they touch and flash from red to white while the squid makes its escape.

Many other cephalopods can shed arms when attacked, but only deletron, as far as we know, has arms adapted to actually fight back while the rest of the animal flees. It’s called “attack autonomy,” and is known in only a handful of other animals, most notably in honeybees, whose stings continue to pump venom after tearing free from the body.

Cuttlefish are well renowned for both their intelligence and their amazing camouflage abilities, even capable of “animating” patterns on their skin to confuse their prey. While most will try to blend in with their surroundings, however, the aptly named “flamboyant” cuttlefish displays an intense, flowery color scheme to warn predators of its highly poisonous flesh. Stranger still, it’s one of the poorest swimmers of any squid or cuttlefish, and instead “walks” along the sea floor, using two of its arms as “front legs” and two muscular flaps of skin as “hind legs.” It’s the only mollusk with a quadrupedal gait, like many of us vertebrates. Crawling up to small prey, it shoots out its two tentacles in a manner that may remind you of a frog or chameleon.

Also known as “argonauts,” this extremely unusual, poorly researched and seldom-seen group of octopuses are named for the thin, papery shells secreted by the females and carried with them as mobile nests for their eggs and young. Males, who live only to reproduce, are as little as a twentieth the female’s size, and die immediately after breaking off one long, sperm-filled tentacle inside the female’s mantle. This reproductive tentacle, always the third right arm, is carried inside a special pouch, giving the dwarf male a seven-armed appearance, and when first discovered broken off inside females, it was mistaken for a new parasitic worm.

Female argonauts are sometimes seen attached to the bells of larger jellyfish, dragging the venomous creatures around with them as defense against predators. Evidence suggests that they also suck food particles from the jelly’s gastric contents, like a parasite, using the other animal as both a food source and a weapon.

One of the strangest looking squid in the abyss, the long-armed or “elbowed” squid is also one of the big ones; while its compact body is only a couple feet in length, its tentacles appear to be up to twenty times that length, the entire creature thought to reach around thirty feet or more. These incredible tentacles seem to be extremely stretchy, all the same length and held apart by jointed “elbows” near the base, a characteristic unseen in any other squid or octopus.

Sluggishly undulating its massive fins, the long-armed squid hovers silently in the water with minimal effort, the ghostly tendrils presumably ensnaring any fish or crustaceans who blunder into them. It’s effectively a squid behaving as a huge jellyfish or Man O’ War, a living, flesh-eating spider’s web spread out in the black void of the abyss.

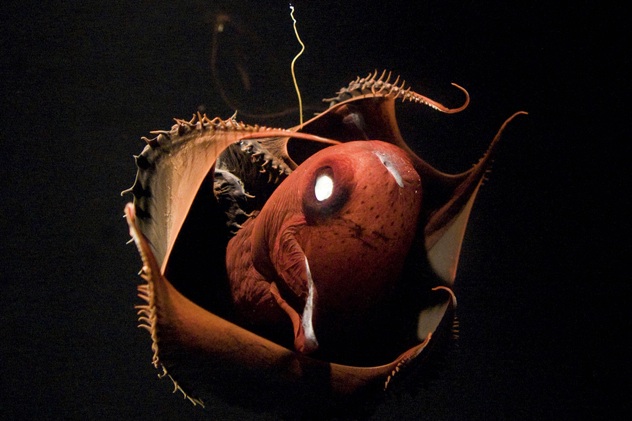

With veiny red skin, luminous, lidded false eyes on the top of its head, tentacles joined in a dark web and finger-like, fleshy spines in place of suckers, this alien entity suits its latin name quite well; “Vampyroteuthis infernalis” means “vampire squid from hell,” and it can be found living in a place referred to as the “Shadow Zone,” or less poetically, the “oxygen minimum zone,” an environment where seawater effectively stagnates and supports little animal life.

Neither a true squid nor an octopus, the vampire is the last survivor of an ancient group known to have grown much larger and swam in warmer, brighter waters over 300,000,000 years in the past, before competition from faster, fiercer sea life drove them back to the harsh shadow zone. Adapted to expend as little energy as possible, their gelatinous bodies float neutrally in the water with little need to actively swim, and their slow metabolism gets by with what little oxygen they can extract from the pelagic wastes they call home.

Though vampire squid have been known to science for more than a century, it took until 2012 to figure out what these floating umbrellas were actually eating at those desolate depths. Long assumed to be carnivorous, we now know that they are in fact the only cephalopods who feed on non-living material, using a pair of thread-like, sticky tendrils to trap particles of decomposing organic detritus, or “marine snow,” as it falls from above. They are primeval, tentacled garbage-men, hiding in the shadow zone to feast on the sea’s collective sewage in peace.

The deep sea abyss may appear pitch-dark to the eyes of us surface dwellers, but many of its inhabitants are so sensitive to light, their surroundings appear bright and blue during the day. This means that for some animals, the abyss is a dark place where dark objects are more difficult see, and luminous objects stand out, but to other animals, it’s the dark objects that are obvious, and luminous objects blend in with that bright, blue seascape only they can perceive. Every creature makes a trade-off with its visual acuity, able to see some, but not all of its predators and prey.

Leave it to a cephalopod to find the weirdest possible loophole. Histioteuthidae, also known as “jewel squid” and “cock eyed squid,” are among the only animals to have a completely different eye on each side of their body. The bulging left eye, twice as large as the other, is ultra-sensitive to light. This is the eye that sees bright, blue water even in the abyss. The right eye, relatively normal and sunken deeper in its socket, sees the abyss as a place of blackness. Aiming the larger eye skyward, toward the light, the squid can see a wider range of creatures than most other abyss dwellers.

The “jewel” moniker comes from the dense, tiny lights completely covering the bodies of these weirdos, which they carefully adjust as the day comes and goes. This allows them to blend in against those bright, blue surroundings only their biggest predators can see, a camouflaging trick called “bioluminescent cryptis.” Some living things inhabit a world so different from ours, they have to shine to hide in the dark.

Jonathan Wojcik is a web cartoonist and amateur biologist born on Halloween. You can find more of his writing on Cracked and his own website, Bogleech.com