Sport

Sport  Sport

Sport  Animals

Animals 10 Strange Times When Species Evolved Backward

Facts

Facts Ten Unexpectedly Fascinating Facts About Rain

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of Australia’s Gruesome Unsolved Wanda Murders

Humans

Humans 10 Unsung Figures Behind Some of History’s Most Famous Journeys

Animals

Animals 10 Species That Refused to Go Extinct

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Weird Things People Used to Do at New Year’s

Our World

Our World 10 Archaeological Discoveries of 2025 That Refined History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Fascinating Facts You Might Not Know About Snow

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Top 10 Things Crypto Was Supposed to Change & What Actually Did

Sport

Sport The 10 Least Credible Superstars in Professional Sports

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Times When Species Evolved Backward

Facts

Facts Ten Unexpectedly Fascinating Facts About Rain

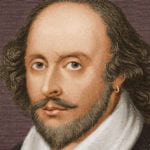

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of Australia’s Gruesome Unsolved Wanda Murders

Humans

Humans 10 Unsung Figures Behind Some of History’s Most Famous Journeys

Animals

Animals 10 Species That Refused to Go Extinct

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Weird Things People Used to Do at New Year’s

Our World

Our World 10 Archaeological Discoveries of 2025 That Refined History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Fascinating Facts You Might Not Know About Snow

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Top 10 Things Crypto Was Supposed to Change & What Actually Did

10 Rare Animals With Bizarre Adaptations

Nature, as the saying goes, finds a way to survive. No matter what adverse conditions may threaten the survival of a creature, individual species will eventually adapt to better survive in their environment—it’s either that, or die. Every animal on this planet has had to grow and change over the course of millennia to become what it is today. And sometimes, that change manifests in truly bizarre ways. These ten rare animals are fantastic examples of the inherent adaptability that is present in all creatures, even if the end result is something completely unexpected.

The maned wolf, or Chrysocyon brachyurus, is a member of the canid family, which includes dogs wolves, and foxes. With its reddish fur and erect ears, the maned wolf looks a lot like your typical red fox, with one glaring exception—it has long, delicate legs that would look more at home on an African gazelle than any kind of wolf. And despite their name, maned wolves aren’t actually wolves—they’re only distantly related to any other canid species, and have managed to carve out their own unique niche in the animal kingdom.

It’s believed that the maned wolf’s distinctive legs are an adaptation to help it survive in the grasslands of South America—in an endless sea of tall grass, the only defense is the ability to observe predators before they can reach you. Their ears are also adapted to the grasslands, allowing the maned wolf to pick up the ever-so-slight rustling sound as rodents—a staple of their diet—scurry through the grass.

Like the flying squirrel, the Sunda flying lemur, or Galeopterus variegatus, has developed a unique way to move among the trees of its native environment—using folds of skin that stretch between its limbs, it glides from branch to branch. From birth to death, Sunda flying lemurs live their entire lives in the rainforest canopies throughout Southeast Asia. Their feet and limbs are well adapted for climbing, but are nearly useless for ground speed, meaning that falling to the ground is an almost certain recipe for death.

The skin membrane, called a patagium, is barely a millimeter thick and covers a surface area nearly six times the size of the rest of their body when fully spread. It’s also efficient—Sunda flying lemurs can glide over 320 feet (100 m) in one jump, and they pull it off without dropping more than 33 feet (10 m) during the flight. The name is misleading because the Sunda flying lemur is neither a lemur nor does it actually fly. It’s actually a type of animal called a colugo, and this one accounts for half of all the known colugos in the world. The other one is called the Philippine flying lemur.

Antelopes look pretty cool no matter what they’re doing, but the gerenuk manages to stand head and shoulders above the rest of the antelope species—literally. Also known as the Waller’s gazelle, gerenuks (Litocranius walleri) have enormously elongated necks and thin, spindly legs, which provide them with a unique feeding opportunity. Rather than graze from grass on the ground like most antelopes, gerenuks stand upright on their hind legs to feed almost exclusively on the leaves and shoots of the acacia trees which dot the African savannas.

It’s no real surprise that gerenuks have evolved to take advantage of such a completely different food source—there are 91 species of antelope in the world, and most of them live in Africa with the gerenuk, and with that kind of competition, someone needs to branch out into a different diet. Unfortunately, while their long, thin legs are perfect for giving them an extra boost to reach acacia leaves, they’re also incredibly fragile, and there have been several cases of gerenuks snapping their leg bones while running across the savannah. It just goes to show how specialization in one area can leave other aspects of life inherently lacking.

The Irrawaddy dolphin, or Orarella brevirostris, is a species of dolphin that lives primarily along the coastlines and estuaries of Southeast Asia, particularly the Bay of Bengal, off the eastern coastline of India. Closely related to orca whales, Irrawaddy dolphins have adapted not through some physical trait, but rather through a rather unique behavior. Over the years, they have developed something of a partnership with local fisherman—they will drive schools of fish towards the fishermen’s nets, and in exchange they have their pick of the helpless fish before the nets are hauled in.

This is an incredible example of nature adapting to human influence, and there is no other animal in the world (in the wild) that interacts this closely with their human counterparts. Even more incredible, there are several reports of court cases from the 19th century in which one fisherman would sue a rival fisherman because “his” Irrawaddy had helped the rival.

Deer are high on most people’s lists of friendly animals. They’re timid, herbivorous, and maybe only pose a threat when they kick out in fear before bouncing off into the woods. Also, they rarely have fangs. The tufted deer of China, however, must have forgotten about that last part. Named for the small tuft of black fur which usually grows along the crest of their heads, their most striking feature is nevertheless the large vampire fangs that grow out of their mouths.

Like antlers, these fangs are used in mating fights between males. Tufted deer do have antlers, but they’re relatively small—so when they fight, they will knock each other around with their antlers first, but once one deer goes down, the second one will instantly go for the vulnerable spots with their fangs, which can protrude from their mouths as far as an inch (2.5 cm). As if this deer wasn’t already bizarre, they have also been seen feeding on carrion—dead animals—which is an extremely rare observation in the deer world, to say the least. So not only do they defeat their rivals with fangs, they also eat meat.

That’s not an ant perched on top of another bug—that’s a species of treehopper called the Cyphonia clavata, which has adapted to grow a realistic ant-shaped protrusion on its back. We’ve featured treehoppers in the past, and there really is no limit to the variety of ways these incredible insects evolve to adapt in even the harshest of environments.

In this example, the Cyphonia chose an insect notoriously difficult to prey upon—a local tree ant—and mimicked the structure of that ant, all the way down to the spikes that protrude from the ant’s back—which is why it’s so unappetizing to predators in the first place. This species of treehopper was first discovered in 1788 by Caspar Stroll, an entomologist from Germany, and can be found in the rainforests of Central America.

The Southern red muntjac, also known as the Indian muntjac, or Muntiacus muntjac, is a small deer native to South Asia. Muntjacs have several unique traits that aren’t found in other deer. Because of their most unique feature, they also come with a local name—barking deer. When the deer sense danger, they will make a sound that resembles a short, harsh bark (like a dog), alerting other deer in the herd to flee. Depending on the danger, these spurts of barking can last longer than an hour at a time.

They also differ from other deer species in other ways—like the tufted deer, muntjacs also have short canine fangs that they use during mating season. However, unlike tuft deer, muntjacs have larger antlers that grow in an incredibly unique shape on the tops of their heads.

Birds often feature large, ornate bunches of feathers which they use during mating rituals. The peacock is a great example of that behavior. However, a lesser known—yet equally impressive—example is the Amazonian Royal Flycatcher, Latin name Onychorhynchus coronatus coronatus. Relatively small, Amazonian Royal Flycatchers are about six and a half inches (16.5 cm) long and, as the name suggests, are found primarily in the Amazon Jungle of South America.

However, while most bird species only have one sex that displays vibrant colors (usually the male), both sexes of Amazonian Royal Flycatcher display large feathered plumes on top of their heads. The female’s is usually yellow, and the male’s is a fiery orange red. Curiously, Amazonian Royal Flycatchers only spread their feathered crest during mating season—and while being handled by humans.

Deep in the Virachey National Park of Cambodia lives a very unique species of ant. The fish-hook ant, or Polyrhachis bihamata, lives in colonies of millions of ants inside hollowed out logs on the forest floor. What’s so unusual about them is the double fish hook protrusions that grow from their backs. As would be expected, these are defensive mechanisms—they’re sharp enough to serve as a powerful predator deterrent. When they were documented by RAP scientists in 2007, one researcher found out first hand that the thorns were not only sharp enough to penetrate skin, they also “hooked” into a wound, latching the ant to whatever attacks it. That may not be good news for a solitary ant, but it serves the colony as a whole very well.

But that’s not the only unusual thing about these ants—when their colony is threatened, they will swarm out thousands at a time and the ants will actually hook into each other to create massive clusters, which makes it nearly impossible for any predator to target an individual ant.

So far this newly discovered salamander species doesn’t have a name, but it’s been dubbed the “ET salamander” because of its resemblance to ET the Extraterrestrial from the 1982 film. Found in the rainforests of Ecuador, this salamander has one truly incredible adaptation—it has no lungs. Rather, it “breathes” through its skin, absorbing oxygen from the air around it. The researchers at Conservation International described it as “remarkably ugly,” which is definitely an apt description of the tiny amphibian.

So far, we still don’t know much about the salamander, and more expeditions are being planned to explore the unique biosphere of the Ecuadorian rainforest.