History

History  History

History  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

The 10 Greatest Syndicated Comic Strips In American History

The only criterion for this list is that the entries must all have been syndicated in newspapers, and they must be great. Superhereos like Superman and Batman don’t count.

10 Krazy Kat

Krazy Kat was written and drawn by George Herriman, and ran in the papers from 1913 to 1944. It was the primary influence on Chuck Jones’s Coyote and Roadrunner cartoons. Herriman set it in his native Coconino County, Arizona, where there is a lot of sagebrush desert, but also a lot of beautiful green scenery with mountains and lakes.

The standard comedy of the strip is good old fashioned slapstick, but it has an air of surrealism about it that lends a timeless quality. You might consider it simple by today’s standards, but it was an influence on the majority of cartoonists who followed it.

There are three main characters: Krazy Kat, Ignatz Mouse, and Offissa Bull Pup. Krazy is in love with Ignatz, but Ignatz hates Krazy and is constantly dreaming up more and more complicated plans to throw bricks at Krazy. Krazy is so in love, or so dumb, that s/he thinks Ignatz’s brick-throwing means that Ignatz is in love with him/her.

But before we start throwing out pronouns, keep in mind that Herriman alternates between referring to Krazy as a male or female. This was deliberate. Herriman once explained that Krazy is something like a sprite, or an elf, and has no gender. In several strips, Herriman jokes about the ambiguity. Ignatz Mouse is more or less male, but it never really matters. Krazy speaks in a very weird mixture of dialects, from English to Yiddish.

Bull Pup is definitely male, and always after Ignatz for throwing bricks at Krazy. By the end of the strip, Herriman decided that Krazy and Ignatz were meant for each other and Ignatz started scheming with Krazy to defeat Pup.

The comic even ventures into the “surreal” at times, as there are multiple strips in which Krazy is reading the strip the audience is also reading. Weird. And never dull.

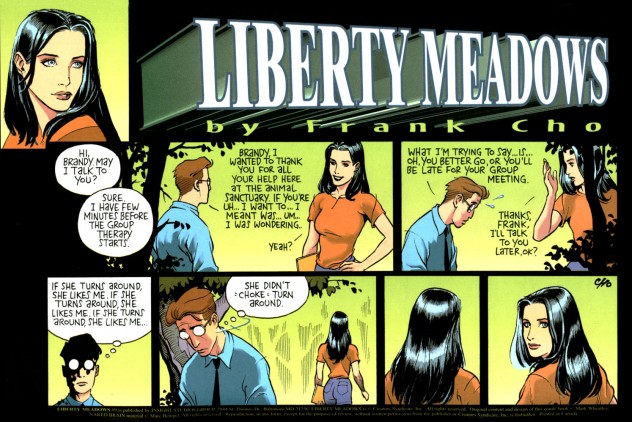

9 Liberty Meadows

Frank Cho syndicated Liberty Meadows from 1997 through 2001. He also published it as a stand-alone comic book until 2004 and again in 2006. This comic fought with its syndicates more than most others since those newspapers require G-rated material. PG at most. They ban bad words, scantily-clad characters, and sex—and Liberty Meadows indulges diabetically in all three.

The humor is more or less the same as the old Looney Tunes shorts: fast-paced and ridiculously slapstick, with the characters beating each other with a variety of hilarious weapons. The stories follow various anthropomorphic animals rehabilitating at Liberty Meadows Animal Hospital under the care of the two head vets, Frank and Brandy. A common source of comedy is that Frank is in love with Brandy, but doesn’t have the nerve to ask her out.

Cho is well known for a lot of work besides this strip, and most includes unbelievably proportioned women, usually dressed in as little as possible (which may explain why the newspaper syndicates had a problem with Liberty Meadows). Brandy is the most famous of all Cho’s female characters. The artist was inspired to draw her based on Lynda Carter (Wonder Woman) and Bettie Page. She is roommates with Jen, who is built precisely the same, but with blonde hair and a mole. She is also the polar opposite of Brandy in personality: Brandy is polite and unassuming, while Jen is the world’s most brazen flirt and a fan of extreme fetishism.

Then there’s Ralph, this lister’s favorite character. He’s a midget circus bear with an almost perpetual squint, a mad genius of mechanical engineering who has been rescued from the death-defying daredevilry that he can now no longer live without. His best friends are Leslie the Bullfrog and Dean the (Male Chauvinist) Pig, who is always trying (and failing) to pick up chicks at the bar.

There’s also Julius, the owner of the sanctuary. His life’s goal is to catch Khan, the baddest catfish in the Milky Way (“Wrath of Khan” homages galore). And Brandy’s pets, Truman the duck and Oscar the dachsund. Cho himself makes many appearances as a chimpanzee. It’s hard to say what the best single storyline is, but the one in which Ralph switches Frank and Dean’s brains is definitely a contender.

8 Garfield

Garfield is the world’s most widely syndicated comic strip. Though it has recently gained a reputation for being bland and apolitical, it actually had far more complex and involved storylines in the ’80s and ’90s.

Examples include Garfield heaving Nermal through the door, mailing Nermal to Abu Dhabi, Garfield loathing Mondays, and this lister’s personal favorite: the week-long Halloween strip of 1989, when Garfield wakes up in a long-since abandoned house, completely alone. There are even some who claim that every subsequent Garfield strip has taken place in that empty house, and are simply the hallucinations of a depressed and lonely cat slowly starving to death.

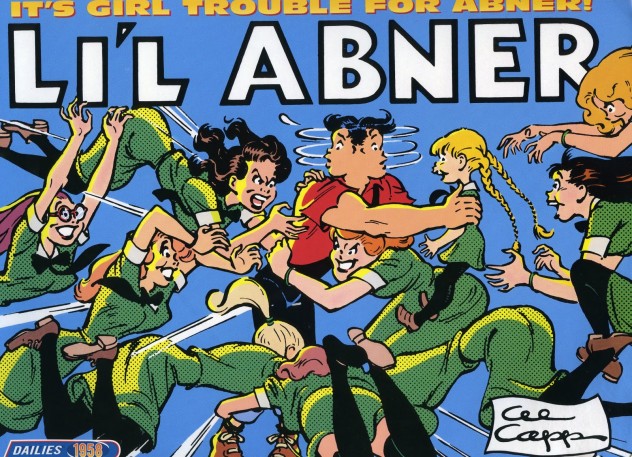

7 Li’l Abner

Al Capp wrote and drew Li’l Abner for 43 years. It tells the story of the extended redneck Yokum family and their friends of Dogpatch, Kentucky. Capp depicted the outside world as depraved and almost hopeless, while Li’l Abner, who is 6 feet 3 inches, stoically remains the bright light. He is somewhat dimwitted, but purely innocent, to the point of ridiculous naivete. 5-year-olds trick him into giving things away, because he sees only the good in everyone.

Li’l Abner is juxtaposed against his two tiny parents, Mammy and Pappy. Pappy is ostensibly the source of Abner’s low IQ, while he gets his honesty from both. Mammy is the boss of the whole strip, settling most disputes with, “Ah has spoken!” If this doesn’t work, she uses an uppercut. She cooks the whole family 8 meals a day of pork chops and turnips. Capp stated that he based Mammy mostly on himself, and liked her the most.

The other main character is Daisy Mae Scragg, of the Yokum’s rival clan and mortal enemies. She is smitten by Abner’s rugged good looks, but he is so dumb that he couldn’t take the hint for 18 years of the strip’s run. His proposal in 1952 was a major media event.

Possibly the most famous character from the strip is Sadie Hawkins, since the fictional Sadie Hawkins Day Dances are actually observed at numerous high schools around the United States.

6 Opus

Opus is one of the more adorable comics here, due in large part to Opus the Penguin’s gigantic nose and extreme naivete. But the other characters give it some raucous humor, and often stray into the realm of politics. One of the few strips to be deliberately ended by its creator Berkeley Breathed, Opus ran from 2003 to 2008. Over the course of the strip’s story line the title character returned from Antarctica to his old home in Bloom County. Opus was originally from the Falkland Islands, some 800 miles from the Antarctic Peninsula.

Opus the Penguin had already been a major character in three other strips by Breathed, Academia Waltz, Bloom County, and Outland, and they are all just as good as Opus. Breathed explained his choice of animal, saying “there was no shortage of cartoon dogs.”

Opus’s friends include Milo Bloom, a 10-year-old journalist who seems to be the wisest character of the strips, Binkley, the most neurotic (which is saying a lot), Steve Dallas, the local defense attorney, and Bill the Cat, who is intended as a parody of the titular character of #8. Bill is possibly the dumbest comic character in funny page history, because he did so many drugs in his youth that he is legally brain dead. Bill has been a heavy metal star, a Chernobyl technician, Donald Trump, and many times a Presidential Candidate.

One of the best storylines involves Opus attempting to step on Milquetoast the Cockroach, winding up in court on charges of sexual molestation, and then finally finding himself in jail. He spends the whole time attempting to explain that he was just trying to kill Milquetoast—who counters, “You lingered.”

5 Doonesbury

Doonsebury is one of the most political strips to appear on the actual funny pages. Garry Trudeau is liberal, and yet the strip is quite popular with both sides of the aisle. Trudeau first wrote Bull Tales, a strip for Yale University’s student paper. Doonesbury is a continuation of the same characters, plus many new ones. This was the first comic strip to win a Pulitzer Prize. It is probably the most notable strip to actually age its characters instead of leaving them time-locked at one age decade after decade.

Trudeau took time off from the strip in 1983 and 1984, during which time he took it to Broadway, graduated the characters from Walden College (based on Yale), and advanced their lives. One of the best jokes was the running storyline of Zonker, the hippie of the group, who attended medical school at Baby Doc College in Haiti. The college refers to Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, the tyrannical despot of Haiti until his forced exile. Zonker won $23 million in the haitian lottery and spent almost all of it to buy his Uncle Duke out of the zombie slave trade.

There are quite a few openly gay characters in the strip, and it has acquired its fair share of controversy over the years because of this and its political nature. Trudeau has no fear at all, and writes the stories according to his own sense of appropriateness—He wrote out Andy Lippincott, a gay character, in 1990 as dying of AIDS. It has been dropped from well over a dozen major newspapers over the last 4 decades, only to be revived to quell the clamoring of fans.

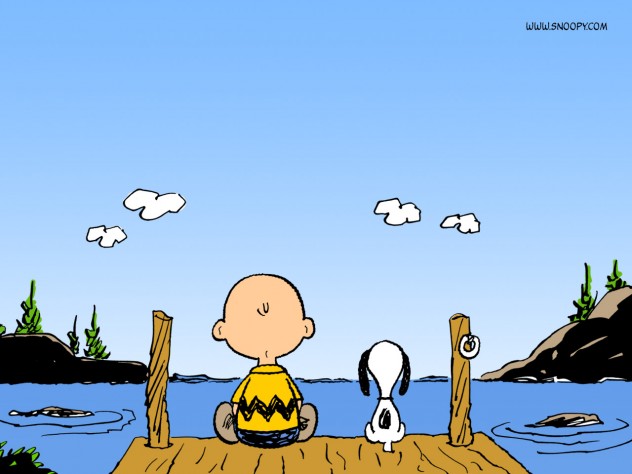

4 Peanuts

Peanuts is probably the most famous strip on this list, at least in America. Charles Schulz wrote and drew this for 50 years, from 1950 to 2000, retiring only when he felt his death imminent. He died that February, and the final strip was published the next day. He was suffering from cancer and Parkinson’s Disease (which made the task of drawing deplorably difficult), but died in his sleep of a heart attack. Well over a dozen other cartoonists paid homage in their strips.

The strip features a motley gang of neighborhood children who get into all sorts of hijinks. The most famous is the immortal Charlie Brown, but others include his sister, Sally, his best friend, Linus van Pelt (who has an inferiority complex treatable only by his blanket), and Linus’s very bossy, know-it-all sister, Lucy. Lucy runs the neighborhood psychiatric stand like a lemonade stand, offering (typically useless) counseling for 5 cents.

But everyone’s favorite character, and even more a mascot for the strip than Charlie Brown, is his pet dog Snoopy. Snoopy is the source of the lion’s share of the strip’s imagination, routinely lost in a world in which he is fighting the Red Baron or attempting to become a successful novelist (though all his fiction begins hopelessly with “It was a dark and stormy night…”). Peanuts has been extraordinarily influential over the decades.

In 50 years, Charlie Brown never got to kick the football. Schulz said this would have been a disservice to him.

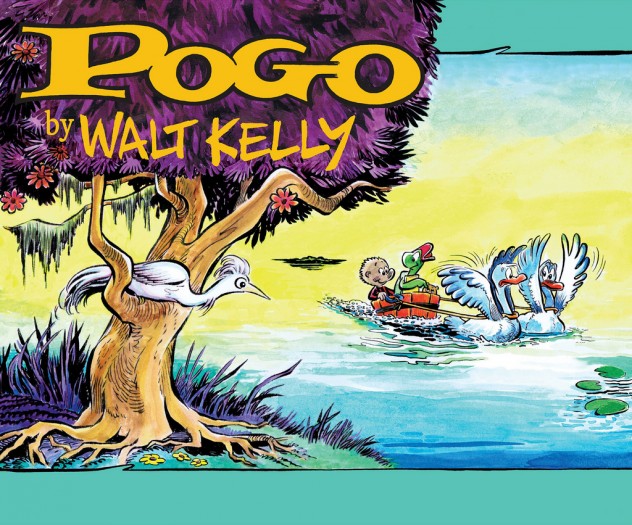

3 Pogo

Written and drawn by Walt Kelly from 1948 to 1975, this one is more satirical than most on this list. It combines slapstick comedy with rather deep philosophy, plus a good amount of poetry. The main characters were almost all animals, led by Pogo Possum, a kind, levelheaded creature with a very high intelligence. Kelly said he was the alter ego we all wish we had. His gentle, patient nature is a reminder of opossums, who always seem to sleep through important events.

His polar opposite is Albert Alligator, the extrovert to his introvert. If Pogo is Winnie the Pooh, Albert is Tigger. He likes to eat anything, whether or not it is food, and there is a running joke throughout the strip of characters momentarily going missing, worrying the rest about whether Albert has eaten them. He is good natured and means well, but is quite irascible and and extreme know-it-all, considering himself the best at everything.

This lister’s favorite character is either Miz Ma’m’selle Hepzibah, a voluptuous skunk, or Miz Beaver, who provides most of the down-to-earth wisdom. She does not trust any of the male characters, but still tries to hook Hepzibah up with one or another of them, usually Pogo, who is the only one Hepzibah ever has any romantic feelings for.

The dialogue is all written in a peculiar dialect, mostly similar to rural Louisiana, and the philosophical musings all take the form of simple, sarcastic and ironic axioms. Perhaps the best, most biting strip is one in which Kelly’s most famous phrase appears, “We have met the enemy and he is us.” The strip was published on Earth Day in 1971, and depicts Pogo and Porkypine, the pessimist of the strip, walking through the woods and stumbling upon a huge pile of man-made garbage. Kelly originally used the phrase to attack Joseph McCarthy in 1953. Pogo is one those rarest of comics that appeals to both children and adults.

Kelly is the first cartoonist whom the Library of Congress asked to draw some strips solely for the Library.

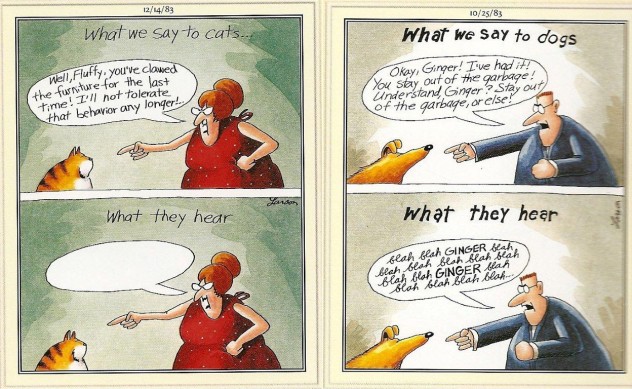

2 The Far Side

Gary Larson explained the single-panel design of The Far Side as proof of his short attention span. There are no storylines in this strip’s history, just random humorous observations, most of them featuring the patently bizarre. Larson claimed he came up with most of his good ideas late at night when his nose was an inch from the paper.

Some of his jokes have become a little too dated to work anymore, like “Psycho III,” featuring a woman in the shower and a tank about to bash through the wall. He never dreamed someone would actually make a Psycho III.

His humor alternates among the macabre (like the one with the granny who has poured concrete over her husband while he was sleeping in his rocking chair), the occasional social commentary (like the one with aliens watching Earth from Mars, and admiring the fireworks of two mushroom clouds centered over America and the Soviet Union), to pure nonsense (“Anatidaephobia: The fear that somewhere, somehow, a duck is looking at you”).

What Larson’s “strip” lacks in storylines it more than makes up for with laughter. This lister’s favorite of his cartoons (a tough call) depicts too 12th century navy ships squaring off, with this caption written underneath: “Although skilled with their pillow arsenal, the Wimpodites were favorite targets of Viking attacks.” The attention to detail is what makes it great: the Viking warship has a dragon as its figurehead, while the Wimpodites have a sheep. The Vikings’ flag shows a dragon’s talons, while the Wimpodites’ displays a daisy, as do their shields.

A close contender with this one is another Medieval gag involving two castles within a few hundred yards of each other. The garrison of one is rushing inside with a big box that reads, “ACME Gate Smasher and Moat Crosser.” The watchman in the other castle’s parapet thinks, “I wonder if I should report this.”

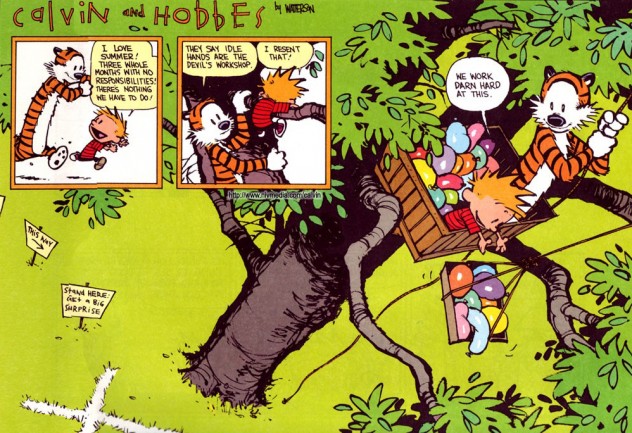

1 Calvin and Hobbes

Bill Watterson drew Calvin & Hobbes from 1985 to 1995, always refusing to merchandise it, and finally retiring the strip for two reasons: his constant fights with his syndicate over this, and because he perceived all the characters to be fully explored and feared the comic would get stale.

Calvin is a 6-year-old boy who gets consistently terrible grades in school, and yet sounds like a doctor of philosophy during his long discussions of religion, politics, and morality with his best friend, Hobbes the stuffed Tiger. Hesitation must be used when referring to Hobbes as imaginary, since he is an entire half of Calvin’s personality, including his conscience. He is the only person to whom Calvin can truly relate, even though every other character in the strip sees Hobbes as a plush toy.

The storylines abound in this one, and picking the best is frankly impossible. Watterson champions the imagination for all the children readers, and also for the adults. The purest example of this is “calvinball,” a wonderfully fun game the title characters make up in protest to all the rules of organized sports. The only absolute rule in calvinball is that you may not play it the same way twice. The rest is a matter of making it up as you go, and it combines elements of cricket, tag, capture the flag, and several others.

Calvin also imagines himself in a variety of alter egos, including Spaceman Spiff, the intrepid intergalactic explorer of strange, new worlds, who fights and escapes from alien monsters; Tracer Bullet, the hard-boiled, film noir detective; and Stupendous Man, defender of liberty, whose arch-nemeses include Baby-Sitter Girl. Her real name is Rosalyn, and she is the only character in the strip who can truly terrify Calvin.

His parents’ names are never given, and he runs them ragged not as often as expected. He also wages an ongoing war with Susie Derkins, the only girl his age with whom he has any real relationship, namely one of tolerance. One of the best stories Watterson ever did, and one of the best in funny page history is that of the little raccoon, whom Calvin and Hobbes rescue from the woods, and who dies of an unknown ailment. Calvin and Hobbes have a protracted discussion on the fragility of life, and why in the world we’re all here. Not a single joke or gag in the whole storyline. But at the end, they hug and say, “Don’t YOU go anywhere.” “Don’t worry.” Never have two comic strip characters loved each other more.

By virtue of its astounding imagination, often philosophical, often serious drama, almost always light-hearted and hilarious, Calvin and Hobbes would take #1 even without considering how dynamically well drawn it is. The over-the-top mannerisms and action of Hobbes tackling Calvin at the doorway after school drew on the great Looney Tunes and Disney shorts, and paved the way for cartoons like Ren and Stimpy.