Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Of The World’s Greatest Lost Treasures

Whether money, priceless artworks, or untold vaults of knowledge, the idea of treasure titillates the minds of nearly every person on Earth. Fortunes have been thrown away in the quest for lost treasure , and the fame and even greater monetary rewards they promise. Here are 10 of the greatest treasures lost to us.

10 The Copper Scroll

The Copper Scroll is one of the 981 texts found at Khirbet Qumran between 1946 and 1956, collectively known as the Dead Sea Scrolls. It holds special significance to Indiana Jones–hopefuls because it purports to be a treasure map. Written on very thin sheets of rolled-up copper, it is the only document found at Khirbet Qumran not written on either parchment or papyrus. In addition, the Hebrew which is inscribed onto it differs from that of the other scrolls. It is of a sort which was more commonly used hundreds of years later.

The Copper Scroll mentions over 60 different locations, with varied amounts of gold and silver said to be buried or hidden at each of them. It is often highly specific, with directions such as “in the gutter which is in the bottom of the rain-water tank . . . ”

No evidence, other than the scroll itself, has ever been found to indicate the existence of these hoards, but that hasn’t stopped a number of people from leading expeditions to find them. Some scholars believe it’s more than likely that the Romans already found all of treasure, as they had a habit of torturing captives in order to find their secret stashes.

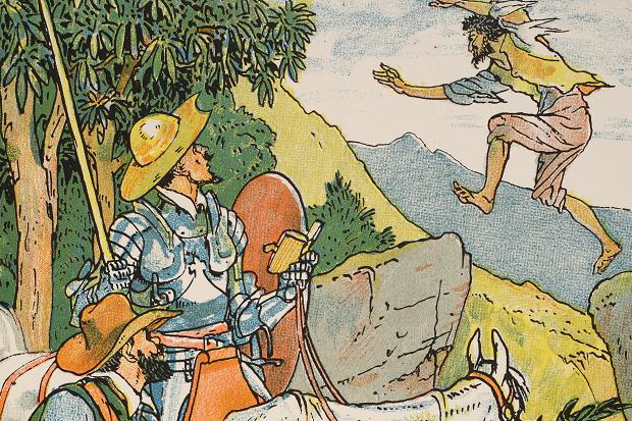

9 The History Of Cardenio

While most people are familiar with William Shakespeare’s famous lost play Love’s Labour’s Won, a less well-known, yet equally sought-after play is The History of Cardenio. Written by Shakespeare and John Fletcher, a man he also collaborated with on Henry VIII and Two Noble Kinsmen, the play was centered on a character in Miguel de Cervantes’ epic novel Don Quixote. Evidence of the play exists in a few places, including a list of the plays to be performed by the King’s Men (Shakespeare’s acting company) in May 1613.

However, the manuscript for the play was lost and never seen again. In the 18th century, Lewis Theobald, a Shakespeare editor and playwright, claimed to have found a copy of the manuscript and “improved” on it, turning it into a play known as Double Falsehood. The manuscript Theobald claimed to have was placed in London’s Covent Garden Playhouse, which burned to the ground in the early 19th century. Whether or not Theobald was telling the truth (and some scholars maintain that he was), we still don’t have the unadulterated version from the greatest playwright who ever lived.

8 On Sphere-Making

Often described as the Leonardo da Vinci of ancient Greece, Archimedes was a brilliant inventor, best known for shouting “Eureka!” and running naked through Syracuse. Aside from public indecency, he also had a flair for invention, which resulted in a device known as a “planetarium.” Basically a sphere which showed the movements of the sun, moon, and planets as viewed from Earth, Archimedes’s planetarium was unmatched in its mechanical intricacy. None are known to have survived, though a device known as the Antikythera mechanism is believed to be closely related.

Very few details of how to construct the inventions of Archimedes were ever written down, as he didn’t like to bother himself with recording mundane things. However, he made an exception for his planetarium, believing it helped people understand the heavens and, therefore, the divine. The intricacies of his design, mechanical gears which rivaled modern clockwork and wouldn’t be seen again for over a thousand years, were all meticulously detailed in his work On Sphere-Making. Unfortunately, all we know of the book itself is writings from other authors, such as the Greek mathematician Pappus.

7 Treasure Of Lima

What list of lost treasures would be complete without a little piracy? Allegedly stashed on the uninhabited Cocos Island (located off the shore of Costa Rica) is a treasure rumored to be worth almost US$300 million. The haul consists of “113 gold religious statues, a life-size Virgin Mary, 200 chests of jewels, 273 swords with jeweled hilts, 1,000 diamonds, solid gold crowns, 150 chalices and hundreds of gold and silver bars,” according to the original inventory—all riches accumulated by the Catholic Church during its time in South America. It was originally given to a British trader named William Thompson for safekeeping. Church officials wanted him to sail around for a few months until the revolutions which had flared up all around Spain’s colonies cooled off.

Unfortunately for the Catholic Church, it was too much of a temptation for Thompson and his men, who killed the guard in charge of watching over the treasure and sailed to Cocos Island. They allegedly buried all the riches, intending to come back later after the heat had died down. But their ship was intercepted by Spanish officials—the crew, save for Thompson and his first mate, were hung for piracy. In return for clemency, Thompson agreed to lead officials to the treasure, but fled into the jungle as soon as he arrived and he, as well as the treasure, was never seen again.

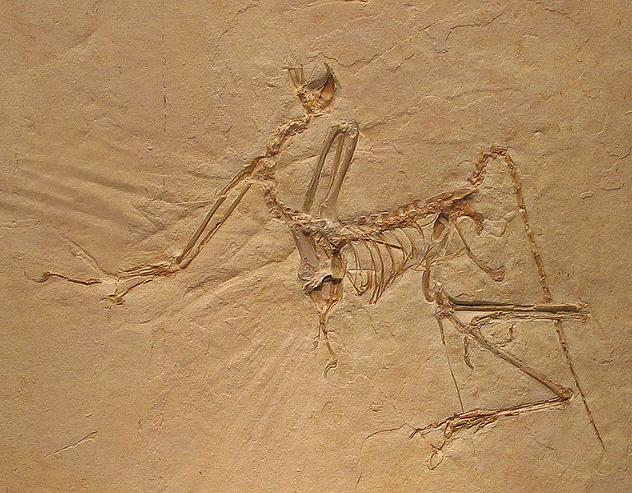

6 The Maxberg Specimen

One of the earliest examples of a transitional fossil (in this case, between a dinosaur and a bird), Archaeopteryx has long been hailed as an important find, both in the fields of paleontology and ornithology. Only 11 relatively complete fossils have ever been found, making each one extremely valuable. The Maxberg Specimen was discovered in 1956 by two men working at a quarry in Germany, which was owned by a man named Eduard Opitsch. At the time, it was only the third Archaeopteryx specimen found. He lent it to the nearby Maxberg Museum for study.

Initially intending to sell it, Opitsch balked when he learned he would have to pay taxes on it. He removed it from the museum and returned it to his house, where it stayed hidden until his death. Afterward, his nephew tried to find it but was unable to; it is presumed to have been stolen in the days following Opitsch’s death. If it is ever found, scientists believe recent technological advancements might allow them to find out even more about the fossil, as it was never properly cleaned.

(The photo above is of the Munich Specimen, likely a juvenile. It was discovered in 1992.)

5 Treasure Of La Noche Triste

On June 30, 1520, Hernan Cortés and his troops were trapped in the capital of Tenochtitlan, surrounded by a furious Aztec population who had just seen their leader killed. (Spanish accounts say that the Aztecs killed him themselves.) In the dead of night, Cortés and his men attempted to escape the city, loaded up with immeasurable amounts of treasure, pilfered during their time in the Aztec capital. However, they were spotted by guards, who raised the alarm, and intense fighting commenced. As many as half of the Spanish troops were killed during the escape.

On what came to be known as La Noche Triste (“The Night of Sorrows”), Cortés lost more than just men and ammunition; he also lost much of the looted treasure. Believed to have been retrieved by the Aztec population in the days that followed, it was said to have been buried in the hills in the surrounding area to keep it from prying Spanish eyes. When Cortés and his men, flush with native volunteers, came back to the city, they questioned all refugees about the treasure but were unable to ever find a trace of it. As much as half of the greatest hoard of treasure ever accumulated in the Americas may still be out there.

4Duchamp’s Fountain

One of the most revolutionary artists of the 20th century, French-American Marcel Duchamp is probably best known for his work Fountain, which was created in 1917. With a desire to challenge what could be considered art, as well as how people value it, he created “readymades,” pieces of artwork that were simply items Duchamp had found lying around somewhere. Fountain was the epitome of this style. It was an ordinary urinal, turned on its side, signed with the pseudonym R. Mutt. Duchamp was already quite famous by this stage and didn’t want audience preconceptions affecting the acceptance of the piece.

It was created for the exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in 1917 and was actually rejected by the committee, who disregarded the fact they were supposed to accept all submitted pieces. (Duchamp actually resigned from the committee in protest.) Duchamp had his friends try and drum up some support by taking pictures and writing articles about the work, but the original ended up lost, never to be seen again. It was most likely thrown out by Duchamp’s photographer friend Alfred Stieglitz. Any existing examples of Fountain , including the one pictured, are artist-authorized reproductions, commissioned later by Duchamp for various reasons.

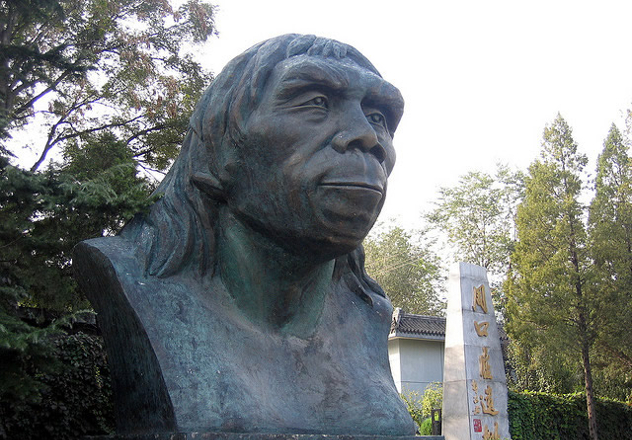

3 Remains Of Peking Man

One of the most important palaeontological finds in human history was a number of skulls discovered in China in the 1920s. They were believed to have belonged to hominids which lived over 500,000 years ago: Homo erectus pekinensis, otherwise known as Peking Man. It is likely the protohumans were killed by ancient lion-sized hyenas, as they were found in what appears to have been the animal’s den. Housed in Peking (Beijing) after being uncovered, they unfortunately became one of the many cultural casualties of World War II.

In September 1941, as tensions in China were escalating, Hu Chengzhi, the lead researcher on the skulls, loaded them onto a ship which was sailing to the US. However, they are generally thought to have been lost at sea, either on a Chinese or American ship which was sunk by the Japanese. (Some far-fetched theories posit that the skulls were ground up as traditional Chinese medicine.) Various attempts at locating the remains have been undertaken, but they have all proved unsuccessful.

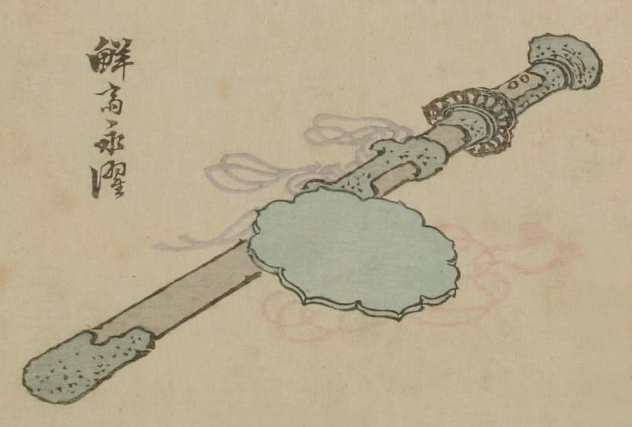

2 The Kusanagi Sword

Its full name is Kusanagi no Tsurugi, which translates to “Grass-Cutting Sword,” and it is one part of a trio of artifacts collectively known as the Imperial Regalia of Japan. Used during a semi-religious ascension ritual which takes place each time a new emperor is crowned, the sword is seen as a symbol of the new ruler’s legitimacy and has been allegedly given to each one for over a thousand years.

The original is commonly believed to be housed in Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya and a copy of the sword is what has been used in its place. However, the real original has been lost, sunk to the bottom of the ocean during a battle in the 12th century, making the one used today a copy of a copy. The sword plays a large role in Japanese mythology and was said to have been found in the body of an eight-headed serpent slain by the storm god Susanoo.

Kusanagi no Tsurugi represents the virtue of valor. The other two artifacts that make up the Imperial Regalia of Japan are the mirror Yata no Kagami, which represents wisdom, and the jewel Yasakani no Magatama, which represents benevolence.

1The Battle Of Anghiari

Often referred to as “The Lost Leonardo,” The Battle of Anghiari is a painting depicting four horsemen in armed combat during the Battle of Anghiari in 1440. Originally planned for the Hall of the Five Hundred, the meeting chamber of the victorious Florentine forces, da Vinci began the painting in 1505. It was going to be the largest he had ever done. Unfortunately, the technical problems which had also plagued The Last Supper overwhelmed da Vinci, and he abandoned the project.

In the years that followed, another painter, Giorgio Vasari, was commissioned to paint a new mural (The Battle of Marciano, pictured) in the same location, and The Battle of Anghiari was lost to history.

However, recent scholars have found compelling evidence to suggest it is still intact underneath Vasari’s mural and that it may have been intentionally saved by Vasari. Some even believe that it was completed and Vasari made up the story of it being left partially finished in order to paint over it. Work has stopped as of today, with local politicians, as well as art historians, hesitant to potentially damage Vasari’s work (a masterpiece in its own right), leaving the possible discovery of da Vinci’s painting in limbo.