Creepy

Creepy  Creepy

Creepy  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

10 Astonishingly Audacious Hoaxes

History has no shortage of fraudsters. They’re usually caught before things go too far, but sometimes people commit a con with such scope and panache that you wonder how they could have possibly gotten away with it. These 10 stories will leave you caught between admiration for the con artist and bafflement that they got as far as they did.

10Sir Edmund Backhouse

Sir Edmund Backhouse was a talented linguist who lived in China around the turn of the 20th century. His most famous work was China Under the Empress Dowager, published in 1910. It was the story of the downfall of Empress Dowager Cixi, based on the diary of one of her aides. Backhouse claimed to have found and translated the diary, but it’s since been revealed that he made the entire thing up.

In 1915, World War I was well underway and Britain was short of weapons. The British War Office contacted Backhouse directly to ask him to negotiate a deal to buy weapons from the Chinese. When Backhouse got back to them, he said he’d arranged a deal worth £2 million (around $340 million today) to buy hundreds of thousands of rifles.

The Brits sent the money, and Backhouse reported that the weapons were being shipped. The British even asked Japan to provide a cruiser to escort the shipment. Along the way, the weapons were frequently “delayed,” and Backhouse had a new excuse each time it happened. When the British contacted China’s top government financier, he claimed that he knew nothing about the deal. But Backhouse had covered his tracks well. He had forged such a convincing array of evidence—including diplomatic communication from Germany opposing the deal—that the British minister in charge concluded that someone in China was behind the problems, because Backhouse was clearly telling the truth.

Backhouse didn’t stop there. His ability to negotiate a deal was so convincing that, after the war, the Chinese government approached him to negotiate a deal with the American Bank Note Company to print 650 million notes. Backhouse was paid £5,600 for the work. Unsurprisingly, the contracts he presented to the Chinese were completely fake, and no notes were printed at all. Backhouse later sold a collection of 58,000 books to the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford—and none of the books even existed. The library never got its money back.

9Han Van Meegeren

Johannes Vermeer is considered one of the greatest Dutch painters of the 17th century, perhaps best known for his masterpiece Girl with a Pearl Earring. When amateur painter Han van Meegeren was arrested in May 1945 for selling Vermeer paintings to the man who founded the Gestapo, Hermann Goering, he was in big trouble. If found guilty of collaboration with the Nazis, his punishment would be death.

Van Meegeren’s defense was simple: He’d painted the pictures himself. He’d produced the forgeries and traded them for genuine works of art that the Nazis had seized. His stated goal was to get the priceless pieces back into Dutch hands. The problem was that no one believed him. One of the paintings Van Meegeren claimed to have painted was described by one of the greatest art historians of the day as “the masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer of Delft.”

The forgeries were too good. Van Meegeren had mixed his paint with resin so that it hardened more quickly. He’d washed genuine 17th-century canvas to get realistic looking cracks, and he’d mostly painted pieces which were suspected to have gone missing from Vermeer’s early days. He’d also avoided models so there wouldn’t be any witnesses, relying instead on his imagination.

This led to perhaps the most unusual criminal trial in history. Van Meegeren offered to paint a fake Vermeer in court so that everyone could watch him do it. Over the course of two painstaking years, he recreated a painting known as Jesus Among the Doctors. He was sentenced to one year in jail, though he died of a heart attack only a month into his sentence. Today, his forgeries are themselves worth millions of dollars.

8The Donation Of Constantine

The Donation of Constantine has been called the “most important forgery of the Middle Ages” and “perhaps the most famous forgery in history.” It’s certainly one of the longest-lasting, as it wasn’t proven to be fraudulent for 600 years.

The document claims to be from the fourth century. It tells a story about Pope Sylvester I curing Roman Emperor Constantine the Great of leprosy. As payment, Constantine declared that the Church was so important that he would forever grant it supremacy over the cities of Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Jerusalem. On top of that, the pope was to have control over Rome’s imperial palace, every single Christian church, and nearly all of Western Europe.

The document was first used during the eighth century to discredit claims made by the Byzantine Empire over territory in Italy. It was again dusted off by Pope Leo IX in 1049 and used in disputes with Europe’s secular leaders, particularly the Holy Roman Emperor.

In 1440, the Italian philosopher Lorenzo Valla analyzed the document. He found that the Latin it was written in hadn’t actually existed in the fourth century. We still don’t know who wrote it, but it’s estimated that the document was created sometime around A.D. 750–800. Pope Stephen II may have been in on it, but it’s widely believed that many of the popes who followed him were themselves fooled by the document.

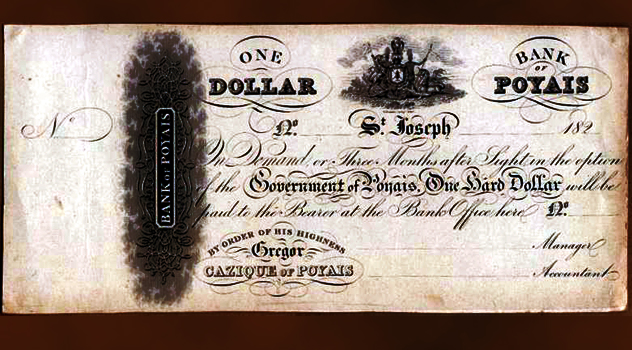

7The Fake Country Of Poyais

Some con artists create a fake company or maybe whip up some fake contracts. Gregor MacGregor didn’t stop there—he faked an entire Central American country. Said to be larger than Wales and located near Honduras, the imaginary land was called Poyais, and MacGregor claimed to be its prince. The Scotsman created a flag, banknotes, a nobility system, and a coat of arms for the country, then he set about making money.

At the time, Britain was in an economic boom and interest rates were low. Investors were looking for higher yields, such as lending to South American governments. Peru, Chile, and Colombia offered returns of six percent. In October 1822, MacGregor offered the same on a £200,000 bond in Poyais. While Poyais had no record of collecting taxes, MacGregor claimed that the revenue from its vast natural resources guaranteed a good return. He ended up raising the equivalent of nearly $6 billion today.

While he raised money in London, he sought settlers in Scotland. He flattered Highlanders, telling them that they had the skills and character necessary to make Poyais a success. In the end, he filled seven ships with people and sent them off to the New World to make their fortunes.

It didn’t go well. The first two shiploads that arrived thought they must be in the wrong place, but they decided to wait it out until MacGregor himself arrived. That plan backfired, and two-thirds of the settlers ended up dead from starvation, disease, and suicide. When word got back to England, the Royal Navy ended up chasing down the other five ships to tell them to turn back.

MacGregor fled to Paris, where he tried the same trick. He was able to recruit 60 new settlers, but the French authorities became suspicious when people began applying for passports to move to Poyais. The French locked him up for a while, and when he got out, he fled to Venezuela to escape angry investors. He never returned to Europe.

6Agent GARBO

Spaniard Juan Pujol Garcia really hated the Nazis. When war broke out, he decided that he needed to help Britain stand against them “for the good of humanity.” He tried to contact the British authorities several times over the next couple of years to offer his services as a spy. Unfortunately, he didn’t really have any experience to offer, so the Brits politely declined. Undeterred, Pujol decided to go freelance.

He contacted Nazi intelligence in Madrid and claimed to be an ally of the Nazis. He told them that he was on his way to London and offered to spy on the Brits. The Nazis accepted, taught Pujol a few things about spying, and told him to recruit a network. The Spaniard moved to Lisbon instead and sent the Nazis updates about what was going on in England from there. Given that he’d never been to the UK and had to make use of the guidebooks in the local library, he did an astonishing job. Even British intelligence was convinced they had a spy in their midst.

When Pujol made contact with MI6 in 1942 and offered to become a double agent, the Brits finally accepted. He was given the codename GARBO and teamed up with an agent named Tomas Harris. Together, they invented a spy network of 27 sub-agents. The con was so impressive that the Germans awarded Pujol the Iron Cross. His false information was vital in covering up the arrangements for D-Day. He also got an MBE from the British, making him perhaps the only person in the war to receive honors from both sides.

5Lin Chunping

Self-made Chinese businessman Lin Chunping became a darling of the country’s ruling Communist Party in January 2012. He had just bought Atlantic Bank, based in Delaware, for $60 million. He was held up as an example of a rags-to-riches tale and given a position on a key political advisory body. The only problem was that the bank didn’t exist.

When someone eventually bothered to run the bank’s name through a search engine, Lin’s fraud very quickly came to light. Lin admitted to “exaggerating” the truth, but when he realized he was in real trouble, he went on the run. He was arrested after two weeks. It turned out that he’d been conning people long before that point. He’s currently serving life in prison for $658 million in tax fraud.

4The Portuguese Bank Note Crisis

Portuguese arms dealer Artur Alves Reis had just been released from jail in 1924 when he presented himself to Waterlow and Sons, a London-based printing company that had a contract to produce banknotes for the Bank of Portugal. Reis told them that he had come to request the printing of 300 million escuados—close to one percent of Portugal’s GDP. It was, he said, to be loaned secretly to Portuguese Angola, so they had to keep quiet.

The money was printed in 500 escuado notes. Despite being printed unofficially, the money consisted of genuine banknotes which were impossible to differentiate from legitimate cash. Reis took the money to Portugal, laundered it, and set up his own bank, which he called the Bank of Angola & Metropole.

Reis wanted to cover his tracks, which meant that he needed access to the Bank of Portugal itself. He decided that taking direct control of the national bank would be the most effective method, so he began buying up all the stock he could find. By September, he owned over 20 percent of its controlling shares. Unfortunately for Reis, that sort of activity raises suspicions, and the scheme was found out by November.

The bank, unable to tell which notes were good, ordered them all taken out of circulation. This led to riots throughout Portugal. The crisis helped reduce confidence in the government, and probably hastened the coup that took place the following year. Reis himself was sentenced to 20 years in prison and died penniless in 1955.

3Yoshitaka Fujii’s Two Decades Of Bunk

Scientific fraud comes in many forms, but the most extreme is simply making things up and publishing them. Yoshitaka Fujii holds the world record for this. The Japanese anesthesiologist completely made up 172 scientific articles over the course of his 19-year career.

In February 2012, he was dismissed from his job at Toho University when it turned out that he hadn’t received ethics approval for eight studies that he’d published. But suspicions that there may be something more going on had been growing for over a decade. A month after Fujii was sacked, a British anesthesiologist published a review which concluded that the results of 168 of Fujii’s papers were only infinitesimally likely to be true.

How could he manage to publish so much for so long? Well, his papers focused on relatively minor aspects of anesthesiology, and he wrote about drugs that weren’t often used in his native Japan. He spread his papers in journals from a wide variety of disciplines, so that different people would be reading them. He also held seven different jobs during that time, perhaps so nobody would have a chance to become suspicious.

On top of all that, the field of anesthesiology seems to be pretty awful at noticing nonsense. While many working in the field claim that they’re no more prone to fraud than the rest of medicine, there have been some other embarrassing cases. In 2010, a German researcher had 90 papers retracted. The year before that, there were 21 papers from a researcher in Massachusetts found to have been based on fraudulent data.

2Vrain-Denis Lucas Doesn’t Even Try

The French forger Vrain-Denis Lucas deserves a mention because of how obviously fake his work was. Born to a relatively poor family in 1818, he moved to Paris at age 33 and instantly landed himself a job as a genealogist. The company he worked for was paid by ambitious rich people to research archives and prove that they had nobility in their pasts. If none could be found, the company faked it to keep their clients happy.

But it was in 1861 that Lucas’s career as a forger really took off. He approached Michel Chasles, one of the most highly regarded mathematicians in the country, with an offer. Lucas had letters from French physicist Blaise Pascal, apparently written to Isaac Newton, which proved that the Frenchman had come up with gravity first. He also had letters from Galileo which proved that the famous astronomer had stolen his ideas from the Dutchman Christiaan Huygens (who was four years old when Galileo published the findings).

Lucas eventually sold 27,000 documents for over 100,000 Francs. He wrote letters from Mary Magdalene and Alexander the Great. They were all in 19th-century French, on modern paper, and mostly talked about how wonderful France was. One letter from Cleopatra, addressed to Julius Caesar, talked about how their son was doing fine and would be taken to Marseilles because of the quality of the air and the fine education system.

The forger spent so long churning out his poor forgeries that he had no time to spend his money. When Chasles eventually caught Lucas showing the letters to other people, authorities stuck Lucas in prison for two years. There’s no record of Lucas after that, so the final years of this unique forger remain a mystery.

1James Macpherson’s Ossian Poem

When James Macpherson left university in the late 1750s, he decided to go traveling. The young Scotsman toured the Highlands, where he found something remarkable—an epic poem, written by someone named Ossian. The poet was the son of Fingal, apparently a third-century Scottish king. Macpherson translated the poem and published it in 1762.

It was astonishingly successful. It was translated into every language in Europe, and Napoleon carried an Italian version with him at all times. The Emperor of France even had paintings commissioned based on the mythological tale. Other European artists were quick to produce their own paintings based on the stories. Places in Scotland were named for the characters, and the town of Selma, Alabama is named for the place King Fingal called home. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Germany’s equivalent of Shakespeare, incorporated parts of Ossian’s poem into his literature.

All this popularity made Macpherson a very rich man, despite the fact that, as you’ve probably guessed, there was no Ossian or Fingal. Macpherson fabricated the entire thing. English writer Samuel Johnson apparently suspected it from the start, but the Scot had plenty of supporters. Today, even though the story behind the poem was nonsense, it’s still regarded as an impressive piece of literature.

Alan has actually made up every single thing he’s ever written on Listverse, and offers his sincere apologies.