History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

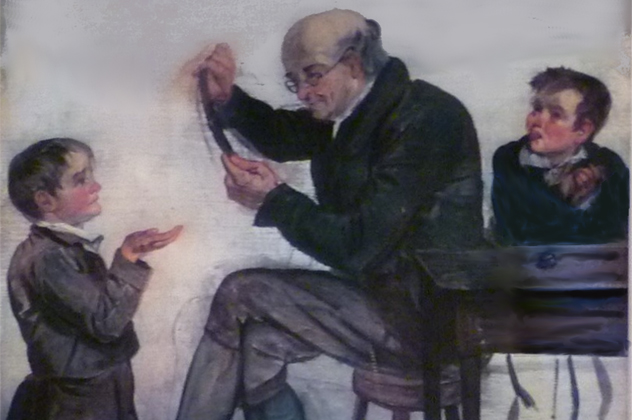

10 Strange Episodes In The History Of Schools

Today, education is highly regulated in many countries. There’s standardized testing, certain milestones that students have to achieve, and requirements that they have to fulfill. It certainly wasn’t always like that, though, and some snapshots of education history will make you glad that we’ve moved on since then.

10St. Augustine’s First British Schools

The structured, teacher-led group sessions that we usually picture as being the setting for modern learning happened in Britain around A.D. 597. They were formed by St. Augustine after the Romans left, so it’s not surprising that they were religious in nature. In fact, the main purpose of these first schools was to make sure that there was no shortage of people who were educated enough to lead a congregation in prayer and song.

St. Augustine founded two different types of schools: the song school and the grammar school. The song school is pretty much what you’d think it would be—it was a place where non-clergy were sent in order to learn all the songs they would need to know in order to sing in the choir. Grammar, on the other hand, didn’t mean the same thing that it does now—in St. Augustine’s time, it first meant teaching Latin to the clergy and then was later expanded to include teaching a variety of subjects (like logic, astronomy, and music) to not just clergy but aspiring statesmen and civil workers.

One of the biggest problems that the schools and their Christian overseers faced was teaching the clergy how to read. While they needed to be fluent in Latin—one of the requirements was being able to read to the congregation—there was also the distinct possibility that the students would be getting their hands on materials that were less than Christian. In some cases, such as with one Bishop Desiderius in France, it was necessary for Pope Gregory to intervene with a very abruptly worded letter expressing his disappointment that students were reading questionable materials with the same breath they used to praise the Lord.

9A Ruling On Corporal Punishment

Corporal punishment has long been in favor—it’s mentioned in the Bible, after all, with Proverbs 29:15 saying, “The rod and reproof give wisdom: but a child left to himself bringeth his mother to shame.” It was something that Thomas Hopley clearly believed when he beat one of his students to death in 1860. Reginald Channell Cancellor was a student in Eastbourne who was found dead in his bed one morning. Completely dressed and covered, Cancellor was first said to have suffered a heart attack in the middle of the night; his schoolmaster, Hopley, pushed for an immediate burial. Stories began to come forward, though, of screams overheard by the servants and blood-covered linens being removed from the room. Instead of declaring the death accidental, doctors looked further and discovered that the boy had been beaten so badly that his legs had been reduced to “jelly.”

Servants’ testimonies pointed the finger at Hopley, and it was found that he had indeed spent several hours during the night beating the boy, after which his wife tried to cover up the mess. According to Hopley, he had grown sick of the boy’s laziness and reluctance to learn; it came out at the trial that Cancellor had been suffering from “water in the brain.” The schoolmaster’s defense was that he was exercising what he called “reasonable chastisement,” reinforced by the idea that he had previously gotten permission from Cancellor’s father to do whatever he needed to in order to get the boy to cooperate in school. Hopley was found guilty and sentenced to four years in jail.

The sentence set a precedent that would last for more than a century, saying that while it was completely acceptable to use moderate corporal punishment where necessary, Hopley went too far.

8The White House Boys

Often the saddest, most brutal chapters in history focus on those who are already in a bad state. In 1900, the Florida State Reform School opened in the Florida panhandle, not far from the state border. It was supposed to be, as the name suggested, a reform school, but not all those who got sent there were hardened criminals—some were just in the wrong place at the wrong time. Since its inception, and mostly through the 1950s and ’60s, horrific stories of abuse came out of the school. Former residents remember beatings, assault, and deaths when the punishments went too far.

According to school records, 31 students died during their stay at the reform school. But when the school, which closed in 2011, was excavated in 2014, 55 bodies were found on the grounds. Many were, of course, unidentified, and remains were sent for DNA testing to try to determine whom they belonged to. In 2009, a group of survivors of the school who had named themselves the “White House Boys” filed a class action lawsuit against the state for negligence, during which they confronted some of the men who had abused them as children. The men lied, and the lawsuit failed.

7Medieval Apprenticeships

Work was much more important than formalized education in the Middle Ages, so children and teenagers were often sent off to apprentice with a professional tradesman. A sort of medieval vocational school, the apprentices certainly didn’t have much choice in the matter. Many were sent off at around 14 years of age, although the upper class would often send their children to be raised by another when they were as young as seven.

The contract between the apprentice and the master often highlighted a rather one-sided relationship, detailing how the master would teach the apprentice and supply him or her with food, but in turn the apprentice would not argue, lie, steal, leave without permission, or look for better wages. There was also a certain amount of abusive discipline that would be understood to go along with the position, and there were many works that specified how a master could best treat his apprentice. The hunting treatise “La Chasse,” written in 14th-century France, held a valuable bit of advice that specified that a boy should be beaten until he was absolutely terrified of failing or disappointing his master.

Numerous letters written between parents and children still exist, and many detail something of a grim life where children write that they’re little more than slaves, not actually learning anything but being forced to simply clean or perform other menial tasks. Many fear being exposed to the plague, while others report rape and other extreme forms of abuse. In some cases, parents would follow up on the claims, and the masters would be prosecuted.

6The Nazi Overhaul Of Education

Education and schools were of the utmost importance in Nazi Germany. Bernhard Rust was appointed Minister of Education, and he overhauled much of the educational system that had been put in place. Not surprisingly, with this overhaul came a change from impartial, scientific learning to Nazi propaganda. We’ve all seen pictures of book burnings, but that was truly only the surface. Textbooks were rewritten, and the emphasis was put on Nazi ideals to the point that even picture books were rewritten to make sure that the youngest of children grew up thinking that it was all right to hate the Jews.

Biology textbooks were written to teach students the physical differences between the Aryan race and the other, lesser races. Physical education was at the top of the list of important subjects, and those who failed could be expelled. Math was taught in a military context, and there were strict limits imposed on universities as to how many female students they could admit. Many students reported their peers to the Gestapo to increase their chances at university acceptance.

The Nazi Teachers’ Association was formed, and Jewish teachers were, of course, dismissed from their positions. Those teachers that remained were under as strict an eye as the students were, as students were encouraged to let their parents or Nazi authorities know if teachings deviated from the accepted curriculum, or if Nazi doctrine was in any way contradicted in class. Every aspect of school was changed—students no longer played “Cowboys and Indians;” instead, they played “Aryans and Jews.”

5Summer Vacation Controversies

Like we discussed previously, summer vacations are a pretty recent thing. It was only at the end of the 19th century that school was formalized, monitored, and subjected to regulations in the United States, and with those regulations came summer vacations. And, because people are people and we’re never happy with anything, there’s been an ongoing controversy over whether or not summer vacations are a good thing. Admittedly, just how much of a difference going to school year-round makes is a hard thing to study because of the enormous amount of variables involved, and the ultimate answer seems to be a resounding, “We’re not really sure.”

In some cases, research says that year-round attendance makes a huge difference for at-risk students in California, but another study of 345,000 students in North Carolina showed that there was no real difference in grades between those who took their summers off and those who had year-round schedules. One of the biggest concerns is that such a long break during the summer leads to students forgetting a lot of what they learned, meaning that there’s a huge amount of wasted time being spent in schools.

While that’s been found to be true, other studies done by NAYRE, the National Association for Year-Round Education, determined the rather conflicting information that traditional school students scored higher on placement tests, but the year-round students showed a marked advantage in the progress of their learning.

Now, some of the generally accepted findings when it comes to the benefits of year-round schedules is that children from low-income families seem to do better in a year-round scheduling format, while other students show little to no overall improvement. It’s also important to note that some schools that are in session all year have schedules that help reduce overcrowding in classrooms; while one group of students is on break, the others are in class. In crowded areas, this alone can make a difference in the classroom experience.

4Gladiator Schools

When most people think of gladiators, they think of Rome. They weren’t just popular in Rome, though, as shown by the recent discovery of a gladiator school in Austria. The institution, home to 80 or more people, was nothing short of a school, prison, and fort all in one. The complex was clearly designed to train gladiators year-round, and even had heated floors for practice combat during the winter months, along with amenities like indoor plumbing and hospitals.

When not training in the main courtyard, gladiators had access to a bath house and were most likely otherwise confined to their chambers, which were little more than jail cells, each measuring about 3 square meters (32 sq ft). More experienced gladiators and teachers seemed to have had more spacious chambers and larger rooms that even show signs of some decoration.

The single entrance is also a reminder that gladiators were slaves, their lives built around showmanship and combat; the entrance of Austria’s gladiator school leads directly to the road to the amphitheater. The compound has yet to be excavated—so far explored solely with ground-penetrating radar—but it’s already been found to be strikingly similar to other schools in Rome and Pompeii. The school also features a graveyard, although the point of the gladiator was to fight, not to die.

3The Altona School Shooting

School violence is nothing new, as we’ve talked about here, with documented cases of students taking firearms to school and using them dating back to the 16th century. Unfortunately, school massacres create tragic, bloody marks in the landscape of the history of schools.

There’s one particularly odd example of school violence that’s a story of contradictions, death, and, by some accounts, unlikely forgiveness. What the accounts agree on is that on October 9, 1902, a schoolteacher in Altona, Canada shot several of his adult coworkers before returning to his classroom. There he singled out three young girls, all from families that had irritated him in some way, and shot all three. Henry Toews then fled, wandering down railroad tracks in an attempt to leave before trying to kill himself. He lived for another year and four months, ultimately dying from his self-inflicted wounds.

Strangely, the account didn’t receive widespread coverage by the media of the time, and accounts in the papers that did run stories about it vary. Sometimes it was premeditated, and other times it wasn’t. Sometimes he was known as a good teacher, and sometimes he was a nasty sort of guy who was unreliable at best and untrustworthy, angry, and bitter at worst. One of the papers says that villagers that had been working in the fields chased Toews down the tracks, finding him still alive after he attempted to kill himself; they took him to the doctor, and he never left the hospital. He later apologized for his actions, and one of the last stories to run about the incident stated that the parents of the girls forgave him. While he only managed to wound two of them, the third died of her injuries.

In a bizarre contrast to today’s relentless media coverage, there are only a couple of articles that were written about the incident, with coverage quickly abandoned in favor of a miner’s strike. The last article to run was about his death.

2Steamboat Ladies

In the early 1900s, the idea of women in a university setting was something that was new to some, foreign to others, and downright horrifying to everyone else. Oxford University professor John William Burgon made his thoughts on the matter of educating women clear when he preached, “Inferior to us God made you, and inferior to the end of time you will remain.” In spite of the fact that more and more people were becoming open to the idea of women in schools, popular votes in Cambridge and Oxford made it impossible for women to be awarded degrees between 1904 and 1907, even if they had completed all the same work as male students.

But during a three-year period, more than 700 of the so-called steamboat ladies hopped on a steamboat and headed to Trinity College in Dublin. While their own alma mater wouldn’t let them have a degree, Trinity College and the University of Dublin bestowed a degree on any woman who made the trip to Ireland and who had completed their home school’s courses. Many of the steamboat ladies went on and achieved fame. There was Eleanor Rathbone, a women’s rights activist who was among the first to speak out against the policies and politics of a rising star named Adolf Hitler. And there was Gertrude Elles, a geologist who earned the medal of Member of the Order of the British Empire during World War I after joining up with the Red Cross.

Last but not least was Philippa Fawcett, who outperformed all her male contemporaries at college mathematics exams and who eventually went on to become the Director of Education of London Country Council in spite of the fact that her name was forbidden to appear on the same list as the men’s names of her class—even though all her scores were higher.

1The Tawse

Corporal punishment certainly isn’t unheard of, but in Scotland, many of the teachers had a preferred weapon of discipline well into the 20th century. It was called the tawse, and it was a long piece of leather that has the business end split into two or three lashes. Making it was an art form; teachers often requested ones that were narrow and had their edges rounded, so they didn’t actually draw any blood. Made on request by leatherworkers for hundreds of years, there were a variety of different makes and models of the tawse, and among the best of them was the Lochgelly.

There were guidelines for its use, including that it was only for serious offenses, girls couldn’t be hit once they were into secondary school, and students should get a verbal warning before getting a beating. And, most bizarrely, we’re not just talking about corporal punishment in the 18th century. Use of the tawse was legal in UK schools through the early 1980s, and it was only made illegal in private schools in 1998. Even into the 1970s, John J Dick Leather Goods, one of the biggest manufacturers of the tawse (in several different sizes), continued to make the tawse in several different varieties—including a miniature one, for humor’s sake.

Finally, in 1976, a case was brought to the European Court of Human Rights, and it was decided that use of the tawse would slowly be faded out of schools. Now, the same store is still making “replicas” of the tawse that they stress are for collectors only. Be that as it may, a quick Google search shows that there are plenty of tawse manufacturers and retailers out there, many of whom have warnings on their web pages that their products are of an adult nature and for adult use only.

![10 Episodes That Were Banned From Television [Videos—Seizure Warning] 10 Episodes That Were Banned From Television [Videos—Seizure Warning]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/image-150x150.jpg)