Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

10 Excruciating Days Inside The Battle Of The Yser

Listverse was in Belgium leading up to the World War I centennial at Flanders Field on October 18, and along the way we traveled the country and experienced everything that incredible region has to offer. Check out what we did on Twitter or Facebook with the hashtag #LVHitsBelgium.

On August 4, 1914, Germany invaded Belgium in the hopes of establishing a northern base of command to get around the fortifications that France had built along the German border. But what was supposed to be a quick operation turned into months of grueling campaigns against a country that just wouldn’t give up. Slowly but surely, however, the Belgians were losing ground, and by October 1914 the German war machine had forced the Belgian army out of Antwerp.

As the ragged and battle-worn soldiers beat a retreat through the tiny town of Nieuwpoort, a decision was made: They’d give it one last-ditch attempt, for hell or for glory. If Germany broke past the line, they’d have access to the entire north of France. But if Nieuwpoort held, that single victory could forever alter the course of history. The German troops approached the city walls, and soldiers on both sides gritted their teeth in anticipation of the days to follow.

The Battle of the Yser (pronounced “eye-sir”) became one of the bloodiest conflicts of the first year of World War I, and thanks to the diary of a Belgian named Emiel Vandenabeele, we know exactly what was happening on the ground as the two armies fought, meter by excruciating meter, over the muddy earth along the fields of the River Yser.

10Sunday, October 18

The Battle Begins

This day was the official start of the battle. The previous day, the mayor of Nieuwpoort had received a letter from the commander of the Belgian army urging him to evacuate the city. The German army had been at the gates since the 16th, and negotiations had finally broken down. The letter stated, “Dear Mayor, I regret to inform you that your city will be shelled by the Germans and possibly also by our own troops if the enemy were to enter your city.”

The mayor took the warning and got as many people out as could safely leave, but the shelling had already started. Emiel Vandenabeele sent his wife and kids through France to England, but he stayed behind. As the last stragglers left the city on the 18th, everyone made a stop at the city hall on their way out—royal decree commanded all citizens to leave a mattress and two blankets for soldiers in the trenches. Everyone who remained in the city hunkered down and prayed that the fighting would end soon.

One hundred sixty thousand Germans hammered at the city while barely 50,000 Belgian soldiers manned the front to hold them back. In the words of Belgian private Raoul Snoeck of the 2nd Line Regiment, “For every enemy we shoot, three others take his place. On top of that, we are told not to shoot too often. ‘These are our last bullets, don’t waste them!’ ”

9Tuesday, October 20

Buried Like Dogs

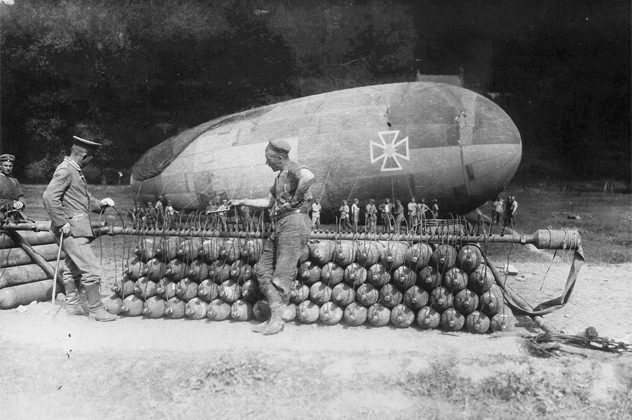

By the third day of the battle, the situation was looking grim for the Belgian army, despite the British troops who had arrived as backup. The trenches were already filled with bodies, and the Belgian soldiers were getting more desperate by the minute. The Germans initially used observation balloons to observe the Belgian positions, but each one was a suicide mission—Belgians shot them down on sight, killing every soldier aboard.

Still the Germans advanced into the city. Emiel watched a soldier on a bicycle get shot down; his body was buried in a nearby garden to get it off the street. After the incident, his diary reads, “No one is buried in the church or in the church yard. Anyone who dies is buried the same day, like a dog.” Off the coast, small British warships were firing cannons over Nieuwpoort and into the German encampments. But no matter how many shots were fired, the Germans couldn’t be stopped.

8Wednesday, October 21

A City In Flames

While the citizens slept in fear, Nieuwpoort began to burn. The German bombs were now hitting major buildings, and the nights were alight with the flames of churches and houses turning to ash. On this day, Emiel’s diary records the burning of a church near his home. He was awakened at midnight by his maid, who was shouting for someone to help put the fire out. By this point, the fourth day of the battle, people slept with their clothes on, even their shoes—if the Germans made it into the city, there would be no time to prepare.

After waking to the screams of his maid, Emiel went outside to see the church billowing balls of fire toward the nearby market. The reverend was already outside, tossing buckets of water onto the flame. People gathered and brought water. The sparks from the church were igniting roofs and yards, the wind carrying them all the way to the harbor. Even before the Germans breached the city, people were fighting to survive. But things would only get worse.

7Thursday, October 22

The Smell Of Defeat

“The Germans are everywhere, as if they had crawled out of the ground. They smell victory, but we resist fiercely. Around us churches, farms and villages are burning. We have not eaten or drunk anything for three days. We sleep next to our fallen comrades, but we have neither the courage nor the strength to bury them. No replacement to take over, no provisioning. The rain is pouring down in buckets.”

The Germans had finally managed to send some troops across the River Yser for the first time in the battle. Each time a patrol landed, they were killed or taken prisoner by the Belgian forces on the other side. But despite the fact that nobody ever returned, the Germans kept sending more. They continued to beat back the Belgians with their superior numbers, and a step at a time the Belgian army fell back away from the river. The German prisoners were paraded through the streets of Nieuwpoort as temporary trophies, but the battle was far from over.

6Friday, October 23

Hunger And Starvation

Hunger and starvation were slowly clenching the city of Nieuwpoort in their icy grip. Both the soldiers and the remaining citizens were languishing under the German onslaught. Emiel summed up the situation with stark finality: “I met a man who was prepared to kill our dog and two cats. The little animals would die of hunger anyway. I think it’s better not to let them suffer.”

The Belgian and French armies blew up the last bridge across the Yser, and the French were toying with the idea of flooding their northern coast. The only reason they didn’t was because doing so would have trapped the Belgian army between the Germans and the floodwaters. They held off on the decision, not yet willing to wholly sacrifice the army that was struggling to keep the enemy from their border. It was a decision that paid off.

5Saturday, October 24

Asleep In The Frozen Mud

The full horrors of World War I’s trench warfare were felt all across the Western Front, and the Belgian army got no more and no less than any other army on the ground. They felt the ground tremble with every bomb, heard each bullet as it whined past. They watched their fellow soldiers cry out and fall to the ground under a bloody mist as a fatal shot hit its mark. They slept in the frozen mud amid the hard brass of spent shell casings. Nieuwpoort converted a warehouse into a dressing station to deal with the mounting casualties of the battle. Shells launched from 25 kilometers (15.5 mi) away suddenly exploded without warning. There was no way to protect oneself.

Nieuwpoort citizens who hadn’t already left were fleeing by Saturday. The mayor took off, abandoning the city to the army. Three days earlier, the last doctor in the city had fled, and now only untrained civilians and army nurses were tending to the wounded soldiers. Half the city had been reduced to rubble, and the other half was sure to follow.

4Monday, October 26

Disaster At The Dam

On the 25th, Emiel Vandenabeele fled the city on foot with his maid and his uncle. Each carried only one small package under their arms by way of provisions. On the same day, a committee in the nearby Belgian town of Veurne decided on a radical plan: They were going to open the floodgates at high tide and let the sea flood the Yser plain.

On the night of October 26, a group of Belgian soldiers led by Captain Robert Thys drove to Nieuwpoort to open the gates. In the dark and cold, afraid to light even a single lamp for fear that the Germans would discover their plan, the soldiers painstakingly pulled open the Kattesas floodgate. It was a disaster—the pressure of the sea water at high tide slammed the gates shut again. The group made a hasty retreat. In the city, the sound of German bombs echoed through the night—another round of shelling had begun, and they were running out of time.

3Tuesday, October 27

A Trickle Of Hope

The next night, Captain Thys and his team tried again, this time bringing ropes to hold open the gates. It worked. The ropes held the floodgates open so that the seawater could stream into the canal, and the ebb doors automatically opened twice a day at high tide. Slowly but surely, the ocean was pouring onto the land. But it was too slowly. The Kattesas sluice was old and narrow, and the canal had a winding route that impeded the flow of the seawater. Floating garbage also kept it back, turning the flood into a trickle.

Meanwhile, French soldiers were keeping all refugees from returning to Nieuwpoort. They had sentries posted at every road, alley, and wooded path, and had taken up the practice of shooting anyone found using the back roads. Exhausted Belgian troops were pouring off the front and into France. Civilians gave the soldiers their mattresses and slept on the bedsprings. It seemed that with each soldier coming off the battlefield, the Germans were one step closer to victory.

2Thursday, October 29

The Floodwaters Surge

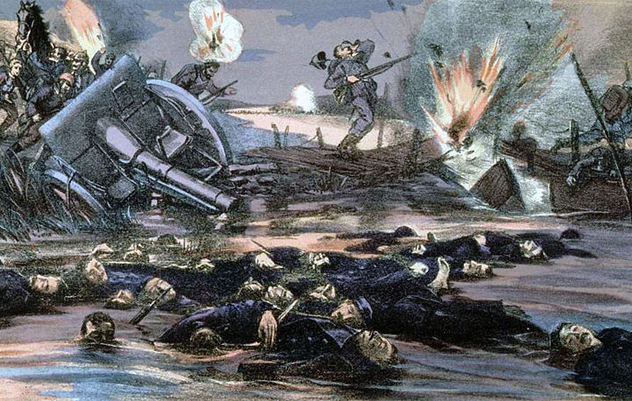

“The Yser runs red with blood and is full of floating bodies, which are pulled out of the water by boats and hooks in order to bury them. Hundreds, thousands of people perish every day. Killing a man seems almost as simple as killing a fly.”

The morning of October 29 dawned cold. Soldiers were now dying from starvation and the weather almost as much as by enemy fire. Few had heard of the government’s plan to flood the plain, and even fewer had seen any effect from the wild scheme. But that night, the troops were again at the sluices, opening the gates to let the sea into the city. It almost seemed like a wasted effort at that point—the Germans were sure to come out victorious. For four days now they had been counting on the flooding to push back the German troops, but the water was moving painfully slowly out of the Kattesas and any flooding the Germans did see was chalked up to the excessive rain of the past few days. Their dreams were crumbling almost as quickly as the city.

Over the next few days, the Belgians managed to open more floodgates, and the floodwaters surged to the south. The city went under, and towns and villages along the Yser plain suffered the same fate. They had destroyed their land, but it had worked—the Germans were at an impasse. For the next four years, Belgium held the German line at the Yser front, halting their advance and changing the tide of the war. Over 76,000 Germans died in the Battle of the Yser, along with 20,000 Belgians, but it was one of the single acts during the war that halted the advance of the German war machine.

1Wednesday, November 11

There And Back Again

“Back to Nieuwpoort.”

These simple words signify the start of a new beginning. Emiel Vandenabeele eventually returned home with his family, only to find the city in ruins. By mid-November, the city was still under the threat of war, but the Germans had ceased their advance and now only rained the occasional mortar fire over the roofs of the returning refugees. The war was far from over and sons and brothers and fathers were far from returning home to their loved ones, but the process of rebuilding had begun.

The Yser plain was kept in a state of flooding until 1918. Emiel was lucky—many people were never able to return home because their houses had been crushed under the floodwaters. It was a dark time for tens of thousands of people, but due to the bravery and persistence of the Belgian soldiers who fought through the night when it seemed like the Sun would never rise again, millions of lives ended up being saved.

This year marks the 100-year anniversary of the start of the Battle of the Yser, and Belgium is paying tribute to all of those who were lost in the conflict. The Light Front Celebration was held on October 17, 2014, in which over 8,000 men, women, and children held a line of flaming torches across the span of the 84-kilometer (52 mi) line that marks the flooding of the Yser. You can read more about the event courtesy of VisitFlanders, whom we wish to thank for making our visit to Belgium possible.