Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

10 Priceless Works Of Art Rescued By The Monuments Men

George Clooney’s film The Monuments Men highlighted a largely forgotten cadre of some 350 men and women known as the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) section. While Clooney’s movie is liberally sprinkled with artistic license, the story of the Monuments Men is unique in history. Never before had a military organization been formed not to steal or destroy artworks but to protect and return looted art to rightful owners.

10Frescoes Of Camposanto Monumentale

When the MFAA was formed by President Franklin Roosevelt in the summer of 1943, the Allies had already driven the Nazis out of North Africa and had invaded Sicily. Initially, MFAA provided maps of towns and cities about to be attacked or bombed, indicating where significant monuments and religious sites were located. But as the Allies moved into Italy, the art historians, architects, archaeologists, and artists who made up MFAA followed close behind.

The MFAA’s mission became urgent when it received news that, during an August 1943 bombing of Milan, a British bomb had landed in the Cloister of the Dead, a courtyard of the Santa Maria delle Grazie Church. It had significantly damaged adjoining buildings, including the church’s refectory, where one of the world’s most famous frescoes was painted: Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper. The bomb had collapsed the refectory’s east wall. Had local officials not erected metal braces, pine scaffolding, and sandbags on both sides of the north wall, da Vinci’s masterpiece would have been lost forever.

Members of MFAA fanned out across Italy, identifying damaged buildings of artistic or architectural significance and repairing them or at least shoring them up against further damage. In August 1944, the Nazis destroyed Florence’s beautiful, irreplaceable bridges over the Arno River, including the Renaissance Ponta Santa Trinita and the medieval Ponte alla Caraia and Ponte alle Grazie. When the MFAA arrived a few days later, they shored up the Torre degli Amidei, a tower built in the Middle Ages, clearing the rubble away from the only surviving bridge, the Ponte Vecchio.

At about the same time, MFAA focused on another town on the Arno, the seaport of Pisa. Cathedral Square is made up of four buildings, the oldest—the Cathedral—built in 1064. The Leaning Tower of Pisa is the most famous of these buildings. The youngest—Camposanto Monumentale or “monumental cemetery”—houses the tombs and memorials of famous Pisans lucky enough to be buried in the sacred soil. That soil allegedly came from Golgotha outside Jerusalem, the place where Jesus was crucified. In some of the sheltered arcades of the Camposanto were 2,000 square meters (6,562 ft2) of frescoes, by far the most important medieval paintings in Europe.

In July 1944, an Allied incendiary bomb ignited the Camposanto’s roof, burned the rafters, and melted the lead in the roof. Nearly all the sculptures and sarcophagi were destroyed, and the lead melted onto the frescoes. The MFAA organized teams of Pisans to scrape off the lead and pick up painted fragments. The restoration and repair of the paintings is still ongoing.

The photo above was taken in the 1890s, long before the damage was done to the fresco The Triumph of Death, attributed to Buonamico Buffalmacco. Notice the beautiful sarcophagus and statues beneath it, now gone.

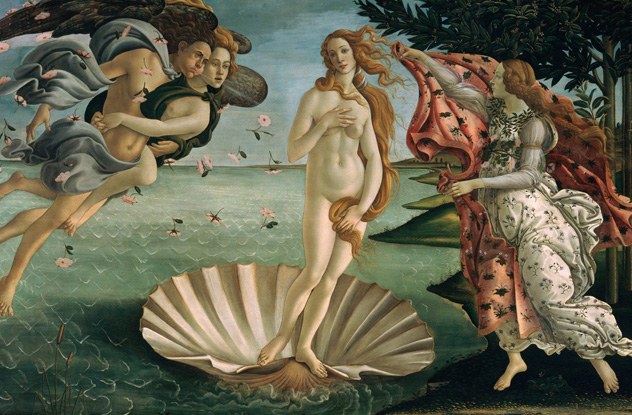

9Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth Of Venus

In 1938, Benito Mussolini escorted Adolf Hitler for two hours in Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, one of the world’s oldest art museums. Hitler was a frustrated artist himself and was already planning his own colossal art museum in his hometown of Linz, Austria. Three years later, Mussolini had Uffizi pack up 34 crates of art and send them to Germany. The pace of outgoing art accelerated after Mussolini was deposed and the Allies made their way toward Tuscany.

Late in July 1944, the Allies arrived on the southern bank of the Arno. On August 13, 1944, the Nazis grabbed a cache of paintings taken from Uffizi and hidden in Alto Adige in northern Italy, among them Luca Signorelli’s The Crucifixion with St. Mary Magdalen. They did not crate the paintings, nor did they protect them with anything but straw. The Nazis drove off with them in open trucks, exposed to the weather and jostled by poor roads. Florence officials tried to stop them, unsuccessfully.

Lucky happenstance led to the discovery of yet another cache of paintings that the Germans had squirreled away in Castello di Montegufoni, a 13th-century castle in Firenze. That July, the Eighth Indian Division took over the castle as their headquarters. While exploring, a Maratha soldier discovered 261 works of art stolen from the Uffizi and Palazzo Pitti, another Florence art museum. Among them was Botticelli’s famous Primavera and his masterpiece, The Birth of Venus. The British and Indian armies turned the paintings over to the MFAA.

The MFAA began a third and final phase to their mission: uncovering artwork stolen by the Nazis, much of it already hidden in Germany. The MFAA found The Crucifixion with St. Mary Magdalen and other Florence works in a Nazi hiding place in a jail cell in San Leonardo, Italy. They returned them to Florence with great fanfare in July 1945.

8Benvenuto Cellini’s Saliera

Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1571) was a Renaissance sculptor and goldsmith whose artworks were almost as famous as his reputation as a rogue. He was banished from Florence after a brawl at the age of 16 and condemned to death at 23 for yet another fight. He fled to Rome, where his metalwork was so admired that he made seals and medals for bishops, cardinals, and popes. They thanked him with pardons for his many crimes, which included embezzlement, immorality, and multiple murders. Imprisoned in Rome in 1537, he escaped from Castel Sant’Angelo on a rope made of sheets. Captured again, he was ultimately released so that he could work for Cardinal d’Este of Ferrara.

Still working for Cardinal d’Este, Cellini presented a wax model of a salt shaker, called a cellar (or, in Italian, Saliera) to the Cardinal. He, however, rejected it because of its expense, and Cellini took it to France and offered it to Frances I. The king commissioned it.

Cellini’s Saliera represents the world, with Neptune, the god of the sea, on one side and Tellus or Terra, the Roman god of land, on the other side. The legs of the two gods are entwined, representing the entwining of land and sea. Neptune rides a pair of seahorses; Tellus rides an elephant. Beside the latter is a miniature temple where pepper—in the form of peppercorn—would be kept. Beside the former is a boat where salt would be kept. Under its ebony base are ivory rollers. When Frances I rolled the Saliera around his table, he was figuratively moving the world. When the king first saw his new salt and pepper dispenser, according to Cellini, he “gasped in amazement and could not take his eyes off it.”

The Saliera is the only surviving work of Cellini made from a precious metal (rolled and sculpted gold) and is, by far, Cellini’s most famous work. It was taken from Vienna’s Kunsthistorische Museum by the Nazis, and the MFAA found it in a huge trove of looted art near Kitzbuhel, Austria. Today, it is worth an estimated $60 million.

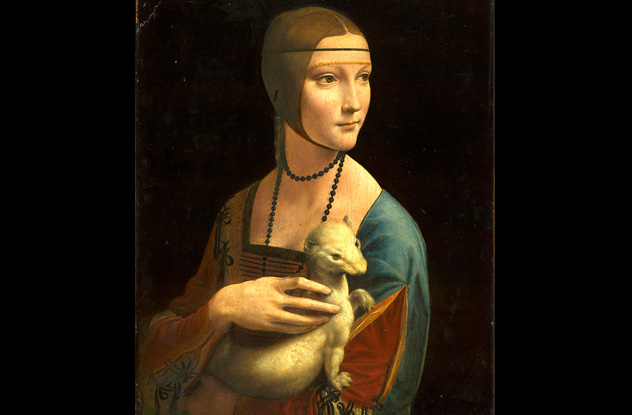

7Leonardo da Vinci’s Lady With An Ermine

Not all looted artworks were destined for the Third Reich. Many high-level Nazis acquired stolen art for their personal collections. Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, at the time of his arrest at the end of the war, possessed an estimated 1,500 looted paintings and sculptures, larger than many art museum collections. He once said, “It used to be called plundering. But today, things have become more humane. In spite of that, I intend to plunder, and do it thoroughly.”

Lady with an Ermine is thought to be an early portrait of da Vinci’s and showcases his brilliance even at a young age. It has no true straight lines, which carries the eye naturally around the image. Da Vinci used a special technique called “catch-lights” to make the girl’s eyes bright and animated. The master pioneered the use of shading—called “smokiness”—which can be seen in the varied tones across her neck and chest. The subject is believed to be Cecilia Gallerani, the teenage mistress of da Vinci’s patron, Ludovico, Duke of Milan.

Almost as soon as the Reich invaded Poland in 1939, da Vinci’s Lady with an Ermine, Rembrandt van Rijn’s Landscape With the Good Samaritan, and Raphael’s Portrait of a Young Man were snatched from Krakow’s Czartoryski Museum as gifts for the Fuhrer. A year later, Hans Frank, Hitler’s governor of Poland, asked that the trio of paintings be returned so he could hang them in his offices. Frank still had them when he escaped Poland ahead of the Soviet army in the winter of 1945. He had lost the Raphael painting by the time he was arrested in Munich in May. While the MFAA returned the da Vinci and Rembrandt to Czartoryski, the Raphael is still missing today.

6Michelangelo’s Madonna And Child

In Clooney’s movie, Donald Jeffries (played by Downton Abbey’s Hugh Bonneville) rushes to the Church of Our Lady in Bruges, Belgium to stop the Nazis from taking Michelangelo’s famous Madonna and Child, commonly called the “Bruges Madonna.” Jeffries has a shoot-out with the Nazi thieves and is killed in the melee. The real-life counterpart for Jeffries was Ronald Balfour, who was actually killed by a shell while removing an altar piece from another church. His death had nothing to do with the Bruges Madonna.

Shortly after D-Day in June 1944, the MFAA landed on the French shore, following the army across France and into Belgium. It’s true that the Bruges Madonna was a priority for the MFAA, but they arrived two days after the Germans had removed the statue and taken it east to the Fatherland.

It wasn’t the first time the Bruges Madonna had been stolen from the church. The statue, the only Michelangelo sculpture to be removed from Italy in the master’s lifetime, had also been stolen in 1794. When French Revolutionaries captured the Austrian Netherlands, the statue was shipped to Paris. It wasn’t until after Napoleon had been defeated that the Madonna was returned to Bruges.

The MFAA found the Bruges Madonna in a salt mine in Altausee, Austria in May 1945. Hitler had stockpiled thousands of works of art in the mines, destined to fill his Linz Fuhrermuseum. Clooney’s movie depicts the MFAA finding the Bruges Madonna minutes before the Russians took over Altausee and rushing the statue out under the Soviets’ noses. Indeed, the Russians did have “Trophy Brigades” bent on plundering Nazi booty, and it’s estimated that they made off with millions of artistic objects. But the reality is that the MFAA had more than a month to remove most of the art from the mine, including the Bruges Madonna.

The photo above shows George Stout (George Clooney’s character) between two members of his team, removing the Madonna from the mine. It was returned to Bruges.

5The Reliquary Bust Of Charlemagne

Reliquaries are repositories of relics—bones or personal effects of honored historical figures or saints—and were found all over medieval Europe. While Charlemagne was not a saint, he was the king of the Franks and Lombards and was the first post-classical Emperor of the West, later to be known as the Holy Roman Empire. When he died 1,200 years ago in 814, he was buried in the Cathedral at Aachen, Germany. About 350 years later, his remains were moved to a golden shrine, still in the cathedral. Sometime in the 14th century, a silver and gold bust was cast with pieces of Charlemagne’s skull cap inside.

The city of Aachen was bombed mercilessly during World War II, and the Cathedral was heavily damaged. When members of the MFAA arrived in October 1944, they lamented that the Cathedral’s sturdy walls had stood for 11 centuries but were now all but destroyed. Fortunately, the Cathedral’s artifacts had been moved, and the MFAA found them in the Siegen copper mine near Westphalia, Germany. Among them was the reliquary bust of Charlemagne.

In February 2014, scientists verified that the skull pieces in the bust are indeed those of Charlemagne.

4Johannes Vermeer’s The Astronomer

Many works of art were not taken from museums or churches but from individual homes. When the Nazis marched into France in 1940, they plundered 36,000 paintings from the City of Light, many of them from personal collections. Jewish collections were particularly targeted. Edouard Alphonse James de Rothschild was both a Jew and an art collector, and among his prized works was The Astronomer by Johannes Vermeer. When he fled Paris, he tried to hide his collection, but the Germans found and looted it. Hermann Goering coveted the Vermeer, but it was a personal favorite of Hitler. Goering reluctantly sent it to the Fuhrer as a gift.

Rothschild was fortunate. Many Jewish art dealers and collectors all over Europe had their artworks confiscated before or after they themselves were sent to concentration camps. Jewish art collector Arthur Feldmann had 750 old master drawings confiscated by the Gestapo when the Germans invaded Brno in what is today the Czech Republic. Arthur died in a Nazi prison.

Thousands of artworks were never claimed after the war, many because the individual owners had died at the hands of the Nazis. Paris’s Louvre has over 1,000 such unclaimed works. The Rothschild family donated The Astronomer to the Louvre after it was discovered in the Altausee salt mine. On the back of it is a black swastika stamp, put there by the Reich.

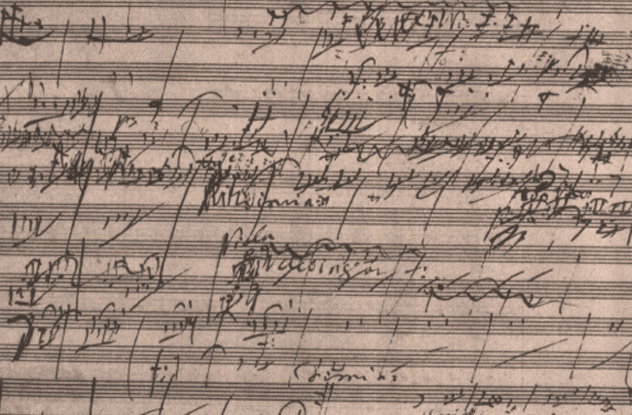

3Ludvig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6 (Original Manuscript)

World War II was particularly hard on German artwork. The Allies bombed the Reich so thoroughly that an estimated 45 percent of the Fatherland’s pre-war monuments and statues were struck, and 60 percent of those struck were completely destroyed. When the Allies dropped 3,900 bombs on Dresden, Germany, the Dresden Gallery was hit. Much of its art had already been hidden, but an estimated 206 paintings were destroyed. The rest were looted by the Soviet army a few months later. Some 450 paintings from the gallery are still missing today.

After the war, the MFAA scoured the Bavarian Alps around Berchtesgaden when a train car filled with Hermann Goering’s stolen art was pillaged by the locals. One woodcutter had hidden Gothic statues and a 13th-century reliquary in his home. A 15th-century Aubusson tapestry had been cut up and divided among local women. The MFAA found one home where the tapestry pieces were used as curtains and a sheet for a child’s bed.

Another area that was heavily bombed was the Rhineland in western Germany. In Bonn, Ludvig van Beethoven’s birth home was damaged, and when the MFAA arrived, they were dismayed to find most of its irreplaceable artifacts gone. Among them was the original manuscript of Beethoven’s sixth symphony. Known as his Pastoral Symphony, Symphony No. 6 is one of Beethoven’s most beloved works.

The MFAA was relieved when they entered the Siegen copper mine, the first treasure trove of looted items they found within Germany. There, they found 600 paintings and 100 sculptures from the likes of Gauguin, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Van Dyke, Renoir, and Rubens. Most of them were from Rhineland churches and museums. And among the piles of art, they found the Reliquary Bust of Charlemagne and Beethoven’s sixth symphony.

2Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Night Watch

Rembrandt’s most famous painting—known originally as Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenhurch—was commissioned by Captain Cocq and 17 members of his civic guards or militia as a portrait of them. Their 18 names appear on a shield on the back wall. They expected to be portrayed in the usual portrait stance, lined up with their faces prominent. But Rembrandt boldly gave his subjects animated stances on this huge canvas, originally 4 by 5 meters (13 by 16 ft).

Using light, colors, motion, and 16 other figures, Rembrandt showed the chaotic first moments when a militia prepared for battle. In the 18th century, art critics and the public attached the name Night Watch to the painting because years of dirt and varnish had darkened it and made the scene appear to be a night excursion.

At the beginning of the war, Rembrandt’s masterpiece was removed from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and spent the first two years moving around Holland. The Nazis eventually found it and in 1942 carted it to the 300-year-old St. Pietersberg repository in a Dutch mountainside near Maastricht. It was conveniently close to the German border.

In October 1944, the MFAA followed a tip to find the repository and saw The Night Watch rolled on a spindle like a carpet. It was already yellowing in the dark repository, the beautiful contrasts in light and color muting. The MFAA moved to have the masterpiece unrolled and mounted on its stretcher. It was returned to the Rijksmuseum.

1Jan van Eyck’s Adoration Of The Mystic Lamb

Arguably the most important work of art in Europe and by far the most irreplaceable work rescued by the MFAA, the Ghent Altarpiece was a huge polyptych weighing over a ton and stretching 4.5 meters wide (14.5 ft) and 3.5 meters tall (11.5 ft). Begun in 1426 as an altarpiece for the cathedral in Ghent, Belgium by Hubert van Eyck, it was finished after his death by his more famous younger brother, Jan. It was the first major oil painting in history and inspired artists around the world to use oil as their choice medium. Most art historians consider it the origin of artistic realism and the bridge between Middle Ages art and the Renaissance.

It also has the distinction of having been stolen all or in part six or seven times, making it the most stolen work of art in history (despite incorrect claims by Guinness). Some of its 12 panels were legally sold to the king of Prussia, and they were displayed in Berlin prior to World War I. As part of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was required to return the pieces to Ghent. Hitler, along with many Germans, considered this one of the many perceived wrongs from this hated treaty. Hitler made it a priority to acquire the altarpiece, and, like most of the artwork destined for his Linz Fuhrermuseum, the masterpiece was hidden in a salt mine in Altausee, Austria. The mine was perfect for housing art with temperatures remaining at 4–8 degrees Celsius (40–47 °F) and a constant humidity of 65 percent.

But in March 1945, Hitler issued the “Nero Decree,” which demanded that anything of value should be destroyed should the Fuhrer die or the Third Reich collapse. The Altausee district leader, August Eigruber, carted into the mine eight crates of 500-kilogram (1,100 lb) bombs to demolish everything. By then, the salt mine housed 6,577 paintings, 2,300 drawings or watercolors, 137 sculptures, 78 pieces of furniture, 122 tapestries, and 1,700 cases of books.

But the salt miners, concerned for their livelihood, sneaked the explosives back out of the mine, and Eigruber discovered the theft too late. The miners then sealed the mine entrance closed until the Allies arrived. The MFAA arrived on May 21.

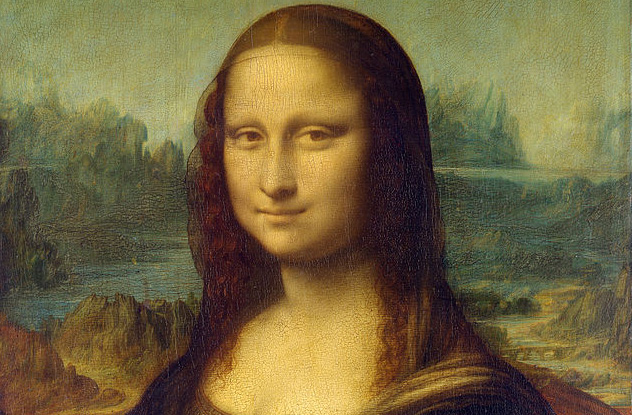

+Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa

The MFAA has been credited with rescuing the most famous painting in the world: the Mona Lisa. Several sources claim that the MFAA helped the French resistance keep it out of Nazi hands. When the National Endowment for the Humanities awarded a medal in 2007 to the Monuments Men Foundation for the Preservation of Art, its website claimed that the Monuments Men were responsible for constructing the bulwark that saved da Vinci’s Last Supper and packing everything in the Louvre—including the Mona Lisa—into crates and shuttling it around France. Both claims are untrue, and it appears the MFAA had little to do with saving the Mona Lisa.

Just before war erupted in 1939, artworks in the Louvre were crated and shuttled to villas and castles all over France. Statues such as Winged Victory of Samothrace and the Venus de Milo were carefully loaded into trucks along with nearly 3,700 paintings. Thirty-eight convoys made their way out of Paris and into the countryside.

According to the records, the museum’s jewel—da Vinci’s Mona Lisa—was bundled on a stretcher and transported out of Paris in a climate-controlled ambulance fitted with heavy-duty shock absorbers. It was sent first to the Chambord Castle in the Loire Valley. The painting moved twice in 1940, in June to Chauvigny and in September to Montauban. Its final move was to Montal in 1942. Her handlers broadcasted her whereabouts in coded messages as she moved. From there, she disappeared.

The claims that the MFAA rescued the Mona Lisa stem from records that say they found it in the Altausee salt mine. But the records also say that this so-called Mona Lisa was “unclaimed,” and they sent it to the Louvre in 1950. The Louvre, however, said the real masterpiece had been returned to the museum on June 16, 1945, five years before.

After some digging, it’s now believed that the MFAA found a 16th-century copy of da Vinci’s painting. That copy is still in the Louvre’s possession. The painting that made its way around France was that copy, and it was captured in 1942 by the Germans and sent to Altausee. Meanwhile, the real da Vinci remained in Paris, hidden in some undisclosed location.

As for the MFAA helping the French resistance hide the famous da Vinci, that claim seems dubious as well. Robert Edsel, one of the surviving members of the MFAA, discussed the Mona Lisa in his blog in January 2014, and he does not claim that the masterpiece was found in Altausee, nor does he say the MFAA helped the French. Instead, he said the French simply hid the masterpiece until after Paris was liberated in August 1944.

Steve is the author of 366 Days in Abraham Lincoln’s Presidency: The Private, Political, and Military Decisions of America’s Greatest President.