History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Brilliant Generals Forgotten By History

By now, everyone’s sick of hearing about how awesome Napoleon and Hannibal were. But there were plenty of other great generals who lacked such good PR. The men on this list shook the world, but, at least in the West, they have been largely forgotten.

10Nader Shah

Eighteenth-century Iran wan’t a great place to grow up. The mighty Safavid Empire had recently crumbled and the Iranian foothills were dominated by petty warlords and chieftains fighting to control the remaining Safavids. From this anarchy emerged Nader Shah, who had a childhood everyone can relate to. Born to a shepherd, he was captured by slavers before the age of 10, then escaped and joined a band of wandering brigands, before rising to become a powerful local chieftain.

Eventually, the deposed Safavid shah, Tahmasb, asked Nader to help him reclaim his throne from Afghan rebels. In 1729, Nader destroyed the Afghans in two battles and returned Tahmasb to the Safavid capital Isfahan. For a time, Nader was content to remain the power behind the throne while he defeated the mighty Ottoman Empire and conquered present-day Georgia and Armenia.

But while Nader was away fighting the Afghans, Tahmasb lost all of his hard-won gains in a foolhardy assault on the Ottomans. Furious, Nader returned from Afghanistan, captured Baghdad, defeated the Ottomans all over again, and exiled the pesky Tahmasb.

Now the undisputed ruler of Persia, Nader soon invaded the mighty Mughal Empire of India. After only a year, Nader had captured the capital of Delhi, returning with a fortune in loot, including the famous Koh-i-Noor diamond. Nader actually captured so much treasure in India that he canceled all taxes for three years and had to build an entire palace just to house it all. But then, at the height of his success, Nader started to go a tad bit crazy.

In 1741, he had his own son blinded for supposedly plotting against him. Paranoid, he had many of his closest supporters murdered and executed thousands of his own citizens for little reason. Meanwhile, his military campaigns were destroying the country’s economy. In 1747, his own officers tried to kill him in his sleep. A fighter to the end, Nader killed two of his attackers before succumbing to his wounds.

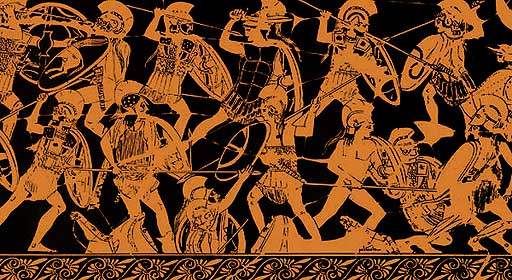

9Pyrrhus Of Epirus

Pyrrhus of Epirus was the kind of guy who never said no to an offer, never finished what he started, and was still astonishingly successful. Hannibal himself rated Pyrrhus as one of the greatest generals in history, second only to Alexander the Great.

Pyrrhus was the classic gambler—except he gambled with entire kingdoms. His wild ways started at age 12, when he became King of Epirus, a mountainous region of Greece. Briefly dethroned, he fought as a mercenary in Syria before taking his country back. Later, he invaded and conquered neighboring Macedon, but was eventually forced to retreat.

His next adventure beckoned in 281 B.C., when the southern Italian city-state of Tarentum asked Pyrrhus to help them against the encroaching Romans. So Pyrrhus responded as anyone would—by abandoning his kingdom in Epirus and sailing across the Adriatic with 25,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry, 2,000 archers, and 20 war elephants. The citizens of Tarentum soon realized Pyrrhus was “helping” by taking over their city, but they didn’t have war elephants, so they just had to deal with it.

In three straight battles, Pyrrhus defeated the armies of Rome. But with each victory, his own army dwindled, since he was far from home and received no reinforcements. Meanwhile, Rome sent army after army. It was following his final, greatest victory that Pyrrhus supposedly uttered his legendary phrase: “If I should ever conquer again in this fashion, it should be my ruin.” A “Pyrrhic victory” now refers to a victory attained at such great cost that it might as well have been a defeat.

Before he left Italy, Pyrrhus apparently predicted even greater wars to follow, saying: “What a battlefield I am leaving for Carthage and Rome.” Always somewhat egotistical, Pyrrhus now began to mint coins with both his and Alexander the Great’s face on them. To prove his similarity to Alexander, he once again invaded Macedon, eventually becoming king. Never content, Pyrrhus quickly left Macedon to attack Sparta. While fighting in the streets of Argos, Pyrrhus died an ignoble death after an old lady threw a floor tile at him from her balcony.

8Subotai

Everyone knows about Genghis Khan, but few know that many of the greatest Mongol conquests were carried out by Subotai, a poor blacksmith whom Genghis adopted.

After helping Genghis defeat the Khwarezm Empire, giving the Mongols control of most of Central Asia, Subotai embarked on what is perhaps the greatest military campaign of all time. With only 20,000 men Subotai decided to take the long way home to Mongolia—by circling the Caspian Sea.

Along the way, Subotai destroyed the Georgian army of King George the Brilliant, pillaging the Georgian countryside while the remaining Georgian forces retreated to their fortified capital. To the defenders’ surprise, Subotai ignored the city and decided to just keep on riding. Or did he? Instead of truly moving on, Subotai returned right before winter, when no one in their right mind would campaign, and slaughtered the rest of the Georgian army.

Crossing the freezing Caucasus Mountains, Subotai found a mighty coalition of local tribes, led by the Cumans, had assembled an army to block his path out of the mountains. With his horsemen trapped in hostile terrain, Subotai simply offered a huge bribe to the Cuman tribe to abandon their allies. After the Cumans vanished in the night, the Mongols easily defeated the disorganized remnants of the coalition. Then they rode after the Cumans, slaughtered their army, and took the bribe back.

After signing a secret treaty in which the Venetians agreed to act as his spies in exchange for the Mongols destroying rival trading posts, Subotai was preparing to return home when word arrived that the Russians had mustered an army of 80,000 men to destroy him. The Mongols didn’t particularly want to fight, but the Russians were arrogant enough to kill 10 of their envoys. That was a mistake. By pretending to retreat, Subotai lured the Russians onto terrain that favored his horsemen, then crushed their army on the banks of the Kalka River. Then he simply headed back to Mongolia.

After defeating the Xia Xia Chinese with Genghis, Subotai grew restless and set off on another grand adventure in 1241, at the ripe age of 67. Arriving in Europe, Subotai demolished the Russians again, burned Kiev to the ground, and appeared on the borders of the powerful Kingdom of Hungary. On the plains of Mohi, Subotai faced 70,000 Hungarian knights with around 50,000 Mongol horsemen.

In a typically bold move, Subotai engaged the Hungarians from three sides, purposefully leaving them one way to escape. When the Hungarians predictably retreated, Subotai’s hidden forces closed in from the fourth direction and annihilated the entire Hungarian army. Just two days earlier, another Mongol force had decisively defeated the Poles at Legnica. Subotai seemed poised to conquer all of Europe, but the Mongols were forced to return home after hearing of the death of Ogedei Khan, Genghis’s successor. Subotai retired from commanding the honorable way, by dying peacefully at the age of 78.

7Baibars

If not for Baibars’ dramatic victory at the Battle of Ain Jalut, the Mongol conquests might never have stopped. Baibars was the first general to halt the Mongol advance, and his victory effectively ended the Mongol golden age.

Before defeating the Mongols, Baibars had been instrumental in turning back King Louis IX’s Seventh Crusade which invaded Egypt. Baibars captured Louis IX himself and exacted a massive ransom from France, which reportedly took two full days to count. But his supreme moment of triumph occurred in 1260, when Kitbuqa, the Mongol commander in Persia, invaded Palestine.

Baibars met Kitbuqa’s army in the Jezreel Valley in central Palestine. To destroy the Mongols, Baibars utilized the Mongol’s greatest trick—the feint. In one of history’s finest ironies, the same maneuver which had won the Mongols all of Asia was finally their own undoing. At Ain Jalut, Baibars engaged the Mongol army and then seemingly retired in defeat. The Mongols, somehow unaware of his strategy, pursued him until Baibars suddenly wheeled back with hidden reinforcements and shattered their army. Kitbuqa was beheaded and the Mongols never again seriously threatened Syria or Palestine. The great age of Mongol conquest had ended.

But Baibars wasn’t finished with his military brilliance. After becoming the Mamluk ruler in 1260 by assassinating his nominal boss, Sultan Qutuz, Baibars began a campaign against the crusader states of Palestine. Over the next two decades, Baibars captured every crusader city except Tyre and Acre, effectively ending the crusading era. By his death in 1277, Baibars had transformed Mamluk Egypt into the dominant Middle Eastern power.

6Epaminondas

Thanks to the homoerotic epic 300, the entire world is obsessed with the martial prowess of the Spartans. Less well-known is Epaminondas, the Theban general who utterly destroyed Spartan power.

Epaminondas was not a classic Greek general—instead of relying on strength, he praised agility. Thebes had long been the ugly step-child of Greek politics, always overshadowed by Athens and Sparta. In 371 B.C., Epaminondas changed that at the epochal Battle of Leuctra.

Instead of distributing his Theban troops evenly from flank to flank, Epaminondas stacked his hoplites (heavy armored spearmen) 50 ranks deep on his left side. The Spartans opposed this with the typical 12 ranks of hoplites. As their weakened right flank retreated, the Thebans’ gargantuan left flank hit the Spartans on their strongest flank, shattering Sparta’s best warriors instantly.

As the Spartan right flank collapsed under the weight of 50 ranks of spearmen, so did the rest of their army. Their defeat was particularly galling since Sparta only allowed a limited class of men to become soldiers and could not replenish such grievous losses. After Leuctra, Epaminondas launched a full invasion of Sparta, helping the Spartan slave class (helots) to revolt.

Epaminondas would eventually launch four invasions of Sparta—and was victorious every time. During his final invasion, at the Battle of Mantinea, he faced off against both Athens and Sparta. The Spartan strategy for the battle was simple—kill Epaminondas. Eventually, they succeeded, but his Thebans still destroyed the Spartan army and as Epaminondas died he proclaimed: “I have lived long enough; for I died unconquered.”

The near-destruction of Sparta and the loss of Thebes greatest general left Greece wide open to Macedonia’s ambitious King Philip. Epaminondas’ innovative tactics were largely copied by Philip and his son, Alexander the Great.

5Khalid Ibn Al-Walid

Few conquests were as startling as the Islamic expansion which followed the Prophet Muhammad’s divine revelations. The first and most decisive decade of this expansion was helmed by Khalid ibn al-Walid, a general who was never defeated, but who is now all but forgotten in the West.

Remarkably, Khalid originally fought against Muhammad at the Battle of Uhud, the only major defeat of the Prophet’s career. But Khalid soon converted, becoming the preeminent Arab commander. In short time, he had united the Arabian Peninsula, which had never been done before, and turned his sights north to the ancient and powerful Byzantine and Sassanid empires.

The Arabs had a unique advantage over their opponents, since many of their troops were mounted on camels. The camels were more durable in desert warfare, and enemy horses were frightened of their smell and bolted when they approached. Khalid first sent his camel corps against the Sassanian armies in A.D. 637, at the Battle of Al-Qadissyah. Khalid’s Arab tribesmen benefited from their longer and thicker arrows, which were able to pierce the Sassanid shields. He used barrages of these deadly arrows to demoralize his opponents, before attacking and scattering the massive Sassanid army. In short time, the 500-year-old empire had fallen and Khalid moved on to the Byzantines.

At the momentous Battle of Yarmuk, the Arabs faced off against the cream of the Byzantine military. Khalid used his Mubarizun, professional duelists, to challenge the Byzantine commanders before the battle. The arrogant Byzantines accepted again and again, until they had lost half of their commanders this way.

After this, the battle raged for six straight days until Al-Walid’s camels destroyed the enemy cavalry and surrounded the Byzantines. The Byzantine army was annihilated and Khalid soon conquered Palestine, Syria, Egypt, and most of Anatolia.

4The Duke Of Marlborough

The Duke of Wellington, England’s most famous general, once noted: “I can conceive nothing greater than Marlborough at the head of an English army.”

Before achieving glory, John Churchill, the future Duke of Marlborough, had a checkered career. In 1692, he was a rising star when he was randomly arrested and thrown in the Tower of London. There were unfounded rumors he was involved in a plot to assassinate the new king, William of Orange. While the rumors were soon proven false, William never really trusted him.

But when the War of Spanish Succession erupted and Louis XIV of France seemed poised to take over all of Europe, William’s successor Anne appointed Marlborough to lead the English, who were allied with the Dutch, Prussians, Austrians, and Savoyards. Somehow, Marlborough molded this hodgepodge alliance into a coherent fighting force and soon ruined Louis XIV’s plans. Until this point, the French had seemed unstoppable, but Marlborough soon ruptured their military mystique.

In 1704, at the Battle of Blenheim, Marlborough’s army killed nearly 40,000 French soldiers, an absurd number for the period. The Battle of Ramillies solidified his military brilliance, as Marlborough feinted an attack on the French left before sending nearly all his troops against the French right, leaving another 15,000 dead Frenchmen.

A few years later, Marlborough destroyed the French army yet again at Oudenaarde, then won a costly victory at Malplaquet in 1709. Marlborough’s victories turned Britain into a formidable European power and halted the spread of French hegemony.

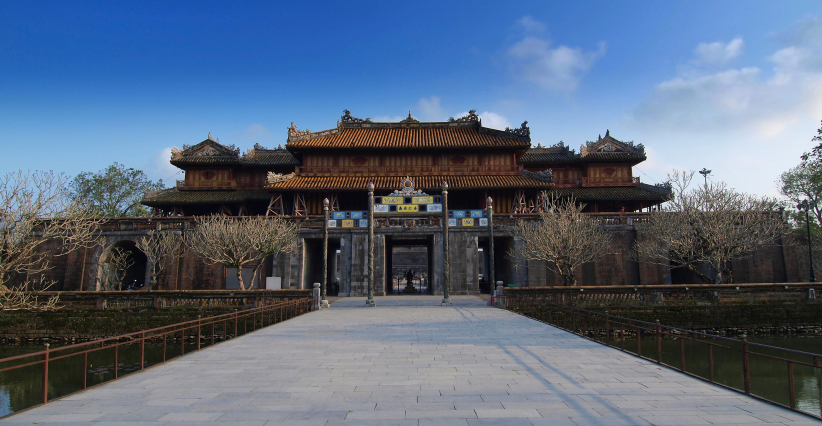

3Nguyen Hue

In the late 18th century, Vietnam was split into two feudal kingdoms ruled by the Trinh and Nguyen families. Both families treated the peasantry horribly, and were generally corrupt, awful people. This created a fertile environment for Nguyen Hue and his three brothers to start the Tay Son Rebellion in 1773. The brothers gained support among the peasantry by redistributing the wealth of landlords and eventually dethroned the Trinh and Nguyen.

However, Hue’s truly legendary status stems from his annihilation of the 200,000-strong Qing Chinese army which invaded Northern Vietnam in 1788. At first, Hue feigned weakness and allowed the Qing to take over much of Northern Vietnam. In the meantime, Hue proclaimed himself King Quang Trung and told his soldiers to celebrate the Tet New Year early.

Soon after, on January 25 (the real Tet), Quang Trung launched his army against the unsuspecting Qing. In order to achieve such tremendous surprise, Quang Trung initiated a unique marching strategy which allowed his troops to cover 600 kilometers (375 mi) in 40 days. Soldiers were grouped in teams of three—two soldiers would carry the third on a hammock. Each soldier took a turn in the hammock, allowing them to march continuously.

The assault itself was led by elite commando groups who held wooden planks covered in water-soaked straw over their heads, negating the Qing’s incendiary rockets. After six straight nights of assaults, the Qing were completely defeated and Vietnam was independent for the next century.

2David IV Of Georgia

Like Estonia and Israel, Georgia has traditionally been conquered by a different massive empire every few years. However, the Georgians are a resilient people, and for a brief period in the Middle Ages, they even became the most powerful kingdom in the region.

The Georgian golden age came under the rule of David IV, also known as David the Builder. When David took control of Georgia in 1089 he was nominally a vassal of the Seljuk Sultanate, which ruled much of the Middle East. David immediately stopped paying tribute to the Seljuks and defeated four armies sent to punish him. Liberating most of modern Georgia, he humanely treated the defeated Muslims, endearing him to his multi-ethnic subjects

But David’s army was quite small and at any moment the Seljuks could have gotten their act together to stamp out Georgian independence. So David decided to import some talent—he brought the entire Cuman-Kipchak tribe from South Russia into Georgia. The Kipchaks received land for 40,000 families, providing David with a powerful new source of manpower.

And David would need all of his imported tribesmen in 1121, when the Seljuks declared a holy war against Georgia. The Muslim army may have numbered between 100,000–250,000 men, while the Georgians could only field a fraction of those numbers.

Like all great generals faced with a hopeless situation, David resorted to trickery, ordering 200 cavalrymen to approach the Turkish camp and indicate they wished to join the Muslim army. As soon as the Turks came out to greet their new soldiers, the entire Georgian army attacked. In the ensuing melee, King David lost three horses, but survived and won the battle. And for a while, Georgia was free.

1Basil The Bulgar-Slayer

The Byzantine Empire’s greatest post-Justinian revival was led by Emperor Basil II in the late 10th century A.D. At this time, Byzantium was surrounded by enemies, with the Fatimid Caliphate in the east and the Second Bulgarian Empire under Tsar Samuel in the west.

First, Basil dealt with the Fatimids, who had been defeating Basil’s incompetent commanders left and right. In response, Basil marched across all of modern Turkey in two weeks, with his sudden arrival causing the Fatimids to retreat in disarray.

But in was in the west that Basil would earn his grisly sobriquet—Bulgar-Slayer. After years of steadily penetrating Bulgarian territory, he annihilated the Bulgarian army at the Battle of Kleidion in 1014. After his victory, Basil blinded 99 out of every 100 Bulgar soldiers, forcing the one remaining guy with eyes to lead the others back to their Tsar. Reportedly, Samuel died of shock after witnessing his army’s return. He was lucky—Basil soon killed every remaining member of the Bulgar royal family in battle, obliterating the Second Bulgarian Empire.

In his spare time, Basil conquered Sicily before passing on, leaving a reinvigorated Byzantium that dominated the Mediterranean.

Geoffrey earned seven liberal arts degrees and is now dealing with that horrible decision. Follow him on Twitter as he tries to become a comedian and something else that makes money.