History

History  History

History  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

10 Rogue Buddhists Who Went Overboard With Violence

Unlike Christianity and Islam, Buddhism enjoys a largely pacific reputation in the West. It’s seen as a meditative religion of love, compassion, and serenity. A 2015 study even suggests that just being exposed to Buddhist words like “dharma” and “nirvana” reduces an individual’s prejudice. Ahimsa, or nonviolence, is central to Buddhism. To speak of “Buddhist violence” or “Buddhist terrorism” seems an oxymoron.

Sadly, the reality is that Buddhists are not immune to radically interpreting their scriptures. Here are the brutal exceptions who uncharacteristically chose to ignore or pervert the Buddha’s clear injunctions against violence in the name of religion.

10Shaolin Monks’ War Of Aggression

Shaolin martial arts have strict rules on how violence should be used. It forbids monks from being the aggressor. They should not kill, not even in self-defense. Only the minimum defensive force necessary to ward off an attack should be inflicted.

These rules notwithstanding, the Shaolin monks joined seventh-century Tang emperor Li Shimin in his war against the usurper Wang Shichong. While some histories relate that Li asked for their assistance, an important chronicle by Pei Cui suggests that the monks attacked Wang, who had previously taken away their land, through their own initiative. Pei suggests that cold political calculation was involved in the monks’ decision. At stake was their continued occupation of the monastery at Cypress Valley, a strategic location coveted by both Li and Wang. The monks debated on who was most likely to win the war. Choosing the wrong side could lead to their banishment from the monastery. Deciding that Li had the best chance, they offered him their support.

Li’s campaign against Wang lasted nearly a year. The monks attacked Wang’s army at Cypress Valley and took his nephew, Wang Renze, prisoner. The war ended with the fall of Wang’s capital of Luoyang in 621.

Li was grateful for the monks’ help and rewarded their monastery but in a letter warned them to desist from further military action. Instead, they should peaceably return to their previous vocation in Buddhist learning.

9Assassination Of King Langdarma

Some Mahayana Buddhist texts teach the unusual concept of “compassionate killing.” This is killing an evil human being without hatred, with the aim of liberating him from bad karma in a future incarnation. The current Dalai Lama explains that it should be carried out only in the most extreme cases: “If someone has resolved to commit a certain crime that would create negative karma, and if there exists no other choice for hindering this person from the crime and thus the highly negative karma that would result for all his future lives, then a pure motivation of compassion would theoretically justify the killing of this person.”

Many of us would agree that this is reasonable from a practical standpoint. Other Buddhists argue that compassion is absolutely incompatible with the act of killing. And this advice has enough wiggle room to encourage those bent on political murder.

An early example is the murder of the tyrannical Tibetan king Langdarma by the monk Lhalung Palgyi Dorje. Langdarma reputedly persecuted Buddhism, and the monk took it upon himself to prevent the total eradication of the religion from the country. Concealing a bow and arrow underneath his flowing black robe, Dorje rode his white horse smeared in charcoal into Lhasa.

He found his victim contemplating the inscription on a pillar near a temple. Taking aim, Dorje shot Langdarma through the heart and escaped to the riverbank. He reversed his robe so that only its white lining would be visible. Dorje spurred the horse into the river, washing away the charcoal. With this brilliant quick-change act, Dorje evaded capture.

Some modern scholars have disputed whether Langdarma really persecuted the Buddhists. It is claimed that the king was a fervent Buddhist himself—the last part of his name comes from “dharma,” or “the path of righteousness.” Whatever the truth, Langdarma’s assassination is seen by Tibetans as a liberation, both for the king as well as the community. The story is used to justify resistance to oppression, specifically the Chinese occupation of Tibet.

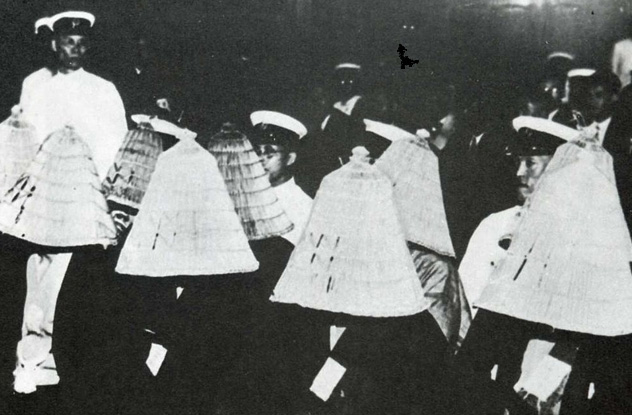

8Sohei, The Warrior Monks

To survive the violent world of feudal Japan, Buddhist monks had to be violent themselves. These monastic holy warriors were called sohei and flourished throughout 700–1500. Originally formed to defend temples, the sohei later found themselves embroiled in wars between feudal aristocrats, often exploiting the situation to enrich their monasteries.

In time, the sohei evolved into a true warrior class who wore armor and carried similar weapons as the samurai. A distinctive sohei weapon was the naginata, a curved blade at the end of a pole used to unseat an enemy on horseback. Monasteries and temples became training camps for new recruits. Later, the sohei became so powerful, they became a threat to the the Shogunate and the imperial court at Kyoto.

The emperor Go-Shirakawa lamented that the three things he couldn’t control were the Kamo River, the roll of the dice, and “the mountain clerics.” The holy warriors were not above attacking even fellow monks, as when they invaded Kiyomizu temple in the midst of a dispute. Only in 1571 was the power of the sohei broken when Oda Nobunaga destroyed their influential temple of Enryakuji.

Later historians sought to whitewash these sohei by dismissing them as “akuso”—evil rogues used by politicians whom Buddhism failed to check because it was going through rough times. But author Mikael Adolphson, in his book The Teeth and Claws of the Buddha, writes: “Buddhism in Japan seems no different from Christianity in Europe . . . Or Islam in Asia Minor, neither do Japanese monastic warriors appear any different from European crusaders or Spanish Moors.”

7Tanaka Chigaku

In the 13th century, while the sohei thrived in medieval Japan’s chaotic conditions, a monk named Nichiren sought to empower ordinary people and thereby transform society through the precepts of the Lotus Sutra. Nichiren believed that the Great Pure Dharma would arise in Japan and spread throughout the world, creating peace and harmony. It never crossed his mind that his benign teachings would be radically reinterpreted in the 20th century by the lay preacher Tanaka Chigaku.

Tanaka’s interpretation of Nichiren Buddhism was largely responsible for justifying Japan’s aggression in Asia in the ’30s and in World War II. Tanaka syncretized lay Nichiren Buddhist piety with the extreme nationalism of native Shinto. From 1914, he spread the ideology of Nichirenism through his organization Kokuchukai (Pillar of the Nation Society). In time, Tanaka converted many government officials, army officers, intellectuals, and common people. His aim was to have his followers eventually take over the Diet and guide Japan to enlightened rule. From there, the world would be evangelized by Japan’s example and embrace Nichirenism.

Tanaka’s creed was a godsend to Japanese imperial ambitions. He taught that Japan had a divine mission to expand and thereby save all Asia from Christianity and communism. He wrote in 1931: “Nichiren is the general of the army that will unite the world . . . The people of Japan are his troops . . . The Nichiren creed is a declaration of war . . . The faith of the Lotus will prepare those going into battle.” Tanaka hailed the First Sino-Japanese War as the first step toward getting the world under one roof. He regarded the Russo-Japanese War as an anti-Christian crusade. Even in old age, Tanaka would preach his vision to Japanese emigrants and soldiers in Korea and Manchuria.

Buddhist soldiers were told that emptiness was the only true reality, so no one was actually being killed by their actions. Tanaka’s endorsement of war for a righteous cause legitimized the violence and atrocities that would destroy millions of lives.

6The League Of Blood

In the early 20th century, the powers of the Japanese emperor were limited by a group of advisers called the genro and the Diet, the legislative body. Many patriotic Japanese chafed at this Western-style model of government and longed for a restoration of the emperor’s absolute rule. Only after the emperor had used his divine mandate to set Japan in order internally could the nation undertake a “war of emancipation of the human race.”

The League of Blood was a terrorist group of Japanese naval officers and civilians led by Buddhist priest Nissho Inoue, who was a disciple of Tanaka Chigaku. Members bound themselves with an oath sealed in their own blood to eliminate the people who they alleged had betrayed national interests and impoverished the peasants and farmers. In 1932, the League plotted the assassinations of 20 leading businessmen and liberal politicians. They hoped that the ensuing chaos would enable the military to seize power and effect the emperor’s restoration.

The League assassins succeeded in killing former finance minister Junnosuke Inoue and the head of the Mitsui trading company, Takuma Dan. The police broke up the conspiracy and arrested its members, including the priest Inoue, on March 11. The naval officers, however, remained undiscovered and continued the plot by killing Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai at his home and grenade-bombing the Mitsubishi Bank, the Bank of Japan, the Seiyukai Party headquarters, and the home of one of the emperor’s advisers.

They even planned to murder Charlie Chaplin, who was then visiting Tokyo, calculating that it would trigger a war with the United States, thereby giving power to the military. The plan was abandoned when it was felt that the US wouldn’t go to war over a comedian. League sympathizers, meanwhile, attacked several power stations, intending to plunge Tokyo in total darkness.

The coup was a failure. The military made no move, and martial law was not declared. Despite the death of the prime minister, the structure of the Japanese government survived.

5Kittiwutto Bhikku

The mid-1970s was a time of rising political tensions in Thailand. The communists were overrunning neighboring Vietnam and Cambodia, where Buddhist monks were murdered by the Khmer Rouge. At home, there were demonstrations by farmers, laborers, and students.

Buddhist monk Kittiwutto Bhikku hated the communists threatening Thailand’s stability. Kittiwutto was a co-leader of the psychological warfare unit Nawapol, a legacy of CIA counterinsurgency operations in the country. He spread the propaganda of “communists as the national enemy” and therefore “non-Thai.” He justified his position in an interview: “I think that even Thais who believe in Buddhism should [kill leftists]. Whoever destroys the nation, religion and king is not a complete man, so to kill them is not like killing a man. We should be convinced that not a man but a devil is killed.”

On October 6, 1976, Kittiwutto’s rhetoric instigated the massacre of students at Thammasat University in Bangkok. The university had always been the center of student activism. Right-wing elements of Nawapol and Border Patrol Police stormed the campus and dragged suspected communist students out. Two were tortured and then beaten as they hung dead from the trees. A female student was sexually assaulted and tortured to death. Three others were piled up with kerosene-soaked tires and burned alive. All the while, spectators cheered and clapped at the spectacle.

Kittiwutto maintained, “It is not a sin to kill communists.” But Thais today look back to the massacre in horror, a stain on their image as a peaceable people.

4Sri Lanka’s Buddhist Nationalists

Sri Lankans regard their island nation as the Dhammadvipa, the isle of the dharma—teachings that enshrine nonviolence. It is therefore tragic and ironic that to defend the most ancient and purest form of dharma against the Hindu Tamils, Sri Lanka’s Buddhists turned to violence.

The Sri Lankan civil war forced the Buddhist majority to do what one scholar had deemed “impossible”: logically reconcile an ideology of violence and intolerance with a faith that, as H. Fielding Hall puts it, is “clean of the stain of blood.” Buddhist monks themselves became the chief proponents of eradicating the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), who were fighting for a homeland of their own north of the island since 1983.

As early as 1956, the All Ceylon Buddhist Congress had made a statement that the dharma was being undermined by the British and the Tamils. After independence, the Sinhalese majority marginalized and disenfranchised the Tamils. It was a monk, Talduwe Somarama, who gunned down Prime Minister Solomon Bandaranaike in 1959 for being too accommodating of the Tamils. In 1972, the Sinhalese made Buddhism the country’s chief religion.

The civil war was one of the longest in Asia, ending only in 2009. Both government forces and LTTE were guilty of massive war crimes, including abduction and recruitment of child soldiers. The world branded LTTE a terrorist organization for carrying out suicide attacks, massacres, and assassinations. But monks like so-called “War Monk” Athurliye Rathana, who backed an all-out military solution instead of dialogue, were as much to blame for the horrors that left more than 70,000 dead. As a self-described occasional extremist, Rathana’s name inspired terror among the Tamils. “This is not Buddhism at all,” a Hindu parliamentarian said. “This is using Buddhism to justify politics and a policy of war.”

3Buddhist Power Force

The end of Sri Lanka’s civil war did not end the violence against non-Buddhist minorities. The rising Buddhist nationalism seeks to subordinate all other ethnicities and religions to its rule. To this end, the Bodu Bala Sena (BBS, Sinhalese for “Buddhist Power Force”) was formed in 2012 by monks Kirama Wimalajothi and Galagoda Aththe Gnanasar. It targets minority Christian and Muslim groups in Sri Lanka whom they believe pose a threat to Sinhalese-Buddhist identity.

Many believe the government supports the BBS agenda. The extremists reserve their special hatred toward Muslims. Muslims are accused of trying to outbreed and eventually outnumber Buddhists. The BBS has incited anti-Muslim riots, destroying mosques and killing people in the process. A BBS leader said that just as the Tamils have been taught a lesson, so will other minorities if they dare “challenge Sri Lankan culture.” It doesn’t help matters that the same intolerance shown by Muslims toward Sinhalese workers in the Middle East is played up by the media.

Likewise, Christian pastors who evangelize Buddhists are attacked. The same treatment goes for “blasphemers” like the Cinnamon Bay Hotel, which was assaulted for hosting a “Buddha Bar” event. Western tourists with Buddha tattoos have been deported.

Pacifist Buddhists who protest against BBS tactics are slandered and even beaten, and the police look the other way. Some have labeled the BBS as a terrorist organization. There are signs that its excesses have eroded support from the public. But even if the BBS disappears, it seems unlikely that the government will disavow its extremist ideology.

2Aum Shinrikyo

Aum Shinrikyo, or Religion of Supreme Truth, is a Japanese cult that syncretizes Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, and Japanese emperor-worship. Shoko Asahara, Aum’s founder, claimed to be the first “enlightened one” since the Buddha. In 1987, Asahara traveled to the Himalayas to study Buddhism and yoga. He had the opportunity to meet the Dalai Lama. It was here in the midst of meditation that Asahara claimed to have achieved final enlightenment and was ordained by Shiva, the god of destruction.

At first, Aum was a peaceful Buddhist New Age sect, seeking spiritual fulfillment through yoga and meditation. The slide toward violence began when a member died during ascetic training. Aum tried to cover up the death in order not to jeopardize the sect’s application for legal recognition. When another member threatened to report to the authorities, Asahara had him murdered, justifying the act as “compassionate killing.” But from then on, Asahara was gripped by paranoia and fear. He and the membership began to feel that they were under siege from an increasingly suspicious public.

When Asahara lost in the parliamentary elections in 1990, he was convinced that there was a conspiracy against Aum. Asahara preached the imminent end of the world in which only members of Aum would survive. The sect began stockpiling weapons. Aum sent a team to Zaire in 1993 to collect Ebola virus samples. They released anthrax spores in Tokyo and planned a massacre using botulin. These plots involving biological weapons failed, and the group turned to chemicals such as sarin.

During the morning rush hour on March 20, 1995, five Aum members left packages of liquid sarin on five cars on three separate railway lines converging on Tokyo’s Kasumigaseki Station. The terrorists punctured the containers and escaped as the liquid leaked out. Chaos and pandemonium ensued in one of the world’s busiest commuter systems. People fell and gasped for breath, blood streaming out of their noses and mouths. Twelve people died, and over 1,000 were injured in Japan’s worst terrorist attack. Asahara and 11 of his followers were sentenced to death for the massacre.

Asahara’s successor steered Aum away from violence and back to its spiritual roots, renaming the sect “Aleph.” But the Japanese government is not convinced, and the group remains under surveillance.

1The Buddhist Bin Laden

Ashwin Wirathu is a controversial Burmese monk notoriously known as the Buddhist bin Laden. He incites sectarian violence with his claims of the Muslim threat to Burma. He displays photos of Islamic violence and calls Muslims “mad dogs” intent on making Myanmar a Muslim state. As a result, hundreds of Muslims have been killed, mosques burned, and thousands more have been driven from their homes in pogroms that have spread throughout the country. Wirathu had already been jailed in 2003 for his direct involvement in the massacre of Muslim families. Time magazine featured him on the cover with the headline “The Face of Buddhist Terror.”

Wirathu fans the flames of anti-Muslim sentiment through the 969 Movement, which he leads. The supremacist group has been described as “Neo-Nazi.” The “9” recalls the nine special attributes of Buddha, the “6” for the six special attributes of his teachings, and the last “9” for the nine special attributes of the Buddhist Sangha, or order. The group distributes propaganda leaflets and videos of Wirathu’s inflammatory sermons. The numbers 969 have become a sort of logo or badge to identify Buddhist-run businesses.

Wirathu denies involvement with violence, but his plan to deal with Muslims in Myanmar is unmistakable: Tame them as you would tame an elephant. Just as one withholds food and water to elephants until they learn their lessons, Wirathu proposes withholding basic rights to Muslims. He urges a boycott of Muslim businesses and urges Buddhists to avoid socializing with them.

Larry is a freelance writer whose main interests are history and chess.