Humans

Humans  Humans

Humans  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

10 Savage Original Reviews Of Classic Works Of Literature

We’re so used to classic works of literature being put up on an intellectual pedestal that it’s hard to empathize with the critics who first encountered them. With little or no hype surrounding the work, they were able to publish reviews without the burden of popular consensus—which meant that they often ended up dismissing a masterpiece as complete garbage.

10The Great Gatsby

While F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 work is one of the leading causes of complaints among high school students and has a fairly spotty record as far as film adaptations go, the story of how Jay Gatsby threw grand parties in an attempt to draw the attention of Daisy Buchanan has captured the imaginations of generations of readers. Not that there was any indication of that when the book was first published. Fitzgerald was extremely disappointed to find that his masterpiece only sold around 21,000 copies, making the author roughly the same amount of money as a short story he’d once written. With that in mind, reviews such as this one from New York Herald Tribune must have stung more than normal:

“The Great Gatsby is purely ephemeral phenomenon . . . a literary lemon meringue.”

After his $2,000 advance to write the book, Fitzgerald only made around $13.00 in Gatsby royalties during his lifetime. He died in 1940, completely missing the period when his book was rediscovered and elevated to the pantheon of American literature. Even worse, he was alive to see the 1926 film version. Rarely has such a classic novel done more to disappoint the author.

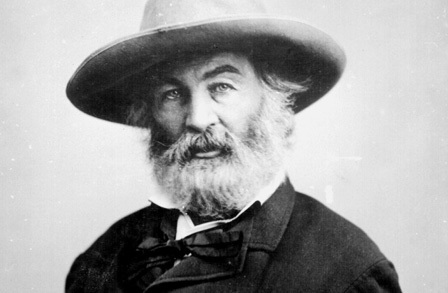

9Leaves Of Grass

Walt Whitman is one of America’s most esteemed poets and Leaves Of Grass has become a touchstone of American literature. This is especially impressive considering that the first two editions of the poetry collection were self-published. When it was finally going to be professionally published, the American Civil War broke out and effectively squashed the third edition. As if that wasn’t enough, the book’s revolutionary style and frank sexual content drew considerable ire and furious reviews. Take this 1855 effort from Edgar Allan Poe’s archnemesis, Rufus Griswold:

“It is impossible to imagine how any man’s fancy could have conceived such a mass of stupid filth, unless he were possessed of the soul of a sentimental donkey that had died of disappointed love.”

And that was still just the tip of the iceberg in terms of the grief Whitman’s work brought him. In 1865, while he was working as a clerk in the Department of the Interior, he left a copy of the book on his desk, where his boss chanced upon it and promptly fired him for writing such stupid filth. Even in 1882, the book was still controversial enough to be banned in Boston as “obscene literature.” Still, it was probably received better than any of our attempts at poetry would be.

8Frankenstein

Frankenstein grew from one of Mary Shelley’s more vivid dreams into one of the most significant combinations of science fiction and horror in literary history. Frankenstein’s monster is one of the most popular and tragic creatures ever to scare an audience, and it must have been especially frightening when it was published in 1818, since a famous public demonstration by Giovanni Aldini had recently shown that something resembling reanimation could be achieved by electrocuting dead human tissue. But it seems that not everyone was impressed, with the Quarterly Review decrying:

“A tissue of horrible and disgusting absurdity . . . Our taste and our judgement alike revolt at this kind of writing.”

The review goes on to blame the book’s shortcomings on the liberal author William Godwin, who “is the patriarch of a literary family whose chief skill is in delineating the wanderings of the intellect.” Godwin was Mary Shelley’s father and she had dedicated the book to him, drawing the ire of many conservative critics in the process. Even a timeless story like Frankenstein got caught up in petty political squabbling.

7The Gettysburg Address

Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 tribute to the tens of thousands of Union soldiers who gave that last full measure of devotion has become one of the most famous speeches in history. That’s partly because its brief length (just 263 words) makes for easy reading and memorization in classrooms. But its intrinsic value, both in terms of historical significance and use of language, should be evident from a quick read. That is, unless you were a writer for the Chicago Times:

“The cheeks of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly, flat and dishwatery utterances.”

The word “silly” was also used by a review in the Harrisburg Patriot & Union. That would likely have stung Lincoln more than the Chicago Times’s insults, since Harrisburg was fairly close to Gettysburg and would have reflected the views of people who’d lived through the Gettysburg campaign more accurately. Still, 150 years later, the Patriot & Union‘s modern successor would print a full retraction of their original review. As if they needed to bother.

6The Grapes Of Wrath

Ostensibly about the Joad family moving from Oklahoma to California, John Steinbeck’s classic 1936 novel is more like a printed docudrama, finding plenty of time for vivid portraits of figures like a mechanically dishonest car dealer. In a sign of the times, the bestseller was actually widely banned, burned, and critically savaged when it was published. In particular, the way the dust bowl victims are exploited throughout the book seemed suspiciously like Communist propaganda to some people. (Ironically, the book was briefly banned in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin.) This review in the San Francisco Examiner is typical of the time:

“The arguments are selected from the customary communistic sources and arguments . . . Consistency is not, and any informed reader knows that it cannot be, a quality either of the Communistic mind or Communist propaganda.”

The negative buzz couldn’t have been all that bad though—the book would go on to receive one of the most acclaimed Hollywood film adaptations of all time, just four years after it was being widely burned.

5Wuthering Heights

A sprawling, non-chronological romance about the orphaned Heathcliff pining for the high-born Catherine, Wuthering Heights was the only book Emily Bronte wrote (under a male alias), but it was more than enough to secure her reputation as a literary great. It has been adapted into several movies, most notably the 1939 version, which is still considered one of the most romantic films ever made. It was also considered a very edgy and controversial book in its day, notable for the cruelty many of the characters display toward each other. Still, even if it was a bit much for its time, this 1848 review from Graham’s Lady Magazine reads like a parody of a stuffy 19th-century reviewer:

“How a human being could have attempted such a book as the present without committing suicide before he had finished a dozen chapters, is a mystery. It is a compound of vulgar depravity and unnatural horrors.”

Graham’s Lady Magazine is now most notable for briefly being edited by Edgar Allan Poe, and for being one of the highest-paying magazines of the day. There seems to be no indication that the critic was being satirical in such a hysterical denunciation of Bronte’s novel.

4Moby-Dick

Herman Melville’s 1851 classic is very different in print than its many adaptations and cultural osmosis would lead you to believe. The revenge-driven Captain Ahab, generally considered much more compelling than the protagonist, Ishmael, doesn’t appear until 28 chapters in. The dense, digressive, literary prose is likely to be dismissed as boring or gratuitous by readers more used to genre fiction. And even in its day, the book attracted prominent bad reviews, such as the one printed in both the London Spectator and the New York International:

“Where it takes the shape of narrative or dramatic fiction, it is phantasmal—an attempted description of what is impossible in nature and without probability in art; it repels the reader instead of attracting him.”

It is also worth noting that Melville was, in this early regard at least, hampered by technology. Another portion of the review mocked the book for having a first-person narrator even though all the characters died at the end. Of course, Ishmael is actually the only survivor, but this is revealed in an epilogue that was chopped off the end of the original UK edition by a printing error. Although the reviewer might have considered that cut a good start rather than a defect.

3‘The Raven’

In 1848, the publication of “The Raven” made Edgar Allan Poe famous in America, but still only netted him the standard $15. It also drew a particularly scathing review from the magazine Southern Literary. Apparently, the writer was so incensed that Poe described the protagonist as being scared by such things as a rap at a door and fluttering curtains, he reached a conclusion that sounds more like the sort of user rating that you’d see on Amazon than a 19th-century literary review:

“It seems as if the author wrote under the influence of opium.”

The review did have some grudging praise for Poe’s use of rhyme and meter, but the insistence that the events of the poem could only affect “a child frightened to the verge of idiocy by terrible ghost stories” make a stronger impression. At least one literary authority from Poe’s time was determined to make sure his horror masterpiece was nevermore considered frightening.

2Winnie The Pooh

By now, stories of the silly old bear and his dim-witted friends in the Hundred Acre Wood have enjoyed nearly a century of popularity in numerous formats, even though author A. A. Milne eventually came to regret writing the series. But his hatred of the books was no match for that of Dorothy Parker, who reviewed 1928’s The House At Pooh Corner for the New Yorker under the pen name Constant Reader. She was especially incensed by a passage where Pooh announces he has added a “tiddely pom” to his favorite song in order to make it more “hummy.” According to Parker:

“And it is that word ‘hummy,’ my darlings, that marks the first place in The House At Pooh Corner at which Tonstant Weader fwowed up.”

Some fans of Parker’s have felt the need to explain this sentiment by observing that she was going through a particularly rough time when she wrote the review and would have hated any book with the slightest hint of sappiness. Others have noted that her articles as Constant Reader were more like comedy routines than serious reviews. So fans of Pooh need not feel defensive over Parker’s harmless words. On the other hand, it’s also possible that The House At Pooh Corner was treacle.

1The Work Of William Shakespeare

One of the first surviving comments on Shakespeare’s work comes from the popular Elizabethan writer Robert Greene. It was written in 1592, when Shakespeare had already had several plays performed. Except for perhaps Richard III and The Taming Of The Shrew, none of them were the classics that the person on the street would come up with if you asked them to name a Shakespeare play today. Nevertheless, Greene was astonishingly dismissive:

“There is an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his tiger’s heart wrapped in a player’s hide supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you; and, being an absolute Johannes Factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country.”

For good measure, Greene’s pamphlet went on to insult Christopher Marlowe. Greene died before his harsh words were published, which spared him a rather unpleasant response. Shakespeare and Marlowe were already so popular that the pamphlet sparked widespread outrage, to the point where Greene’s editor, Henry Chettle, had to publish a “groveling retraction” apologizing to the pair of them. (Greene’s publisher, sensing the way the wind was blowing, had added a clause to the pamphlet saying that he took no responsibility, and was only printing it “upon the peril of Henrye Chettle.”) It seems unlikely that many writers working today could motivate a fan response like that.

Dustin Koski hopes all negative reviews of his short story Sarah Can’t Be Real will become novelties once it achieves classic status.