Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Widespread Historical Myths and the Texts That Started Them

Crime

Crime 10 Incredible Big-Time Art Fraudsters

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Influential Fictional Objects in Cinema History

Animals

Random List

Animals

Animals 10 Strange Times When Species Evolved Backward

Animals

Animals 10 Species That Refused to Go Extinct

Animals

Animals 10 Animals That Humiliated and Harmed Historical Leaders

Animals

Animals Ten Bizarre Creatures from Beneath the Waves

Animals

Animals Ten Mind-Boggling Discoveries About Birds

Animals

Animals Ten Bizarre New Facts About Animals

Animals

Animals 10 Incredible Animals That Can Switch Their Sex

Animals

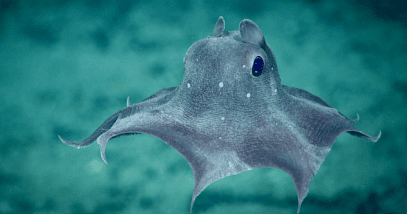

Animals The 10 Weirdest Octopuses In The Ocean

Animals

Animals 10 Orca Quirks That Will Make You Forget the Boat Attacks

Animals

Animals 10 Wild Facts You Might Not Know About Sharks

Animals

Animals 10 Times Desperate Animals Asked People for Help… and Got It

Editor’s Picks

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Psychiatric Diagnoses Of Horror Villains And Their Victims

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Greatest Movie MacGuffins Of All Time

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Iconic Movie And TV Restaurants That Are Actually Real

Movies and TV

Movies and TV