History

History  History

History  Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Cases of Grabbing Defeat from the Jaws of Victory

History

History 10 Common Misconceptions About the Renaissance

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Crazy Things Resulting from Hidden Contract Provisions

Facts

Facts 10 Unusual Facts About Calories

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Days of Humiliation When the Person Should Have Stayed in Bed

Humans

Humans 10 Surprising Ways Game Theory Rules Your Daily Life

Food

Food 10 Popular (and Weird) Ancient Foods

Animals

Animals Ten Bizarre Creatures from Beneath the Waves

Technology

Technology 10 Unexpected Things Scientists Made Using DNA

History

History 10 Events That Unexpectedly Changed American Life

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Cases of Grabbing Defeat from the Jaws of Victory

History

History 10 Common Misconceptions About the Renaissance

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Crazy Things Resulting from Hidden Contract Provisions

Facts

Facts 10 Unusual Facts About Calories

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Days of Humiliation When the Person Should Have Stayed in Bed

Humans

Humans 10 Surprising Ways Game Theory Rules Your Daily Life

Food

Food 10 Popular (and Weird) Ancient Foods

Animals

Animals Ten Bizarre Creatures from Beneath the Waves

Technology

Technology 10 Unexpected Things Scientists Made Using DNA

10 Widely Admired People Who Supported Eugenics

Adolf Hitler was rightly vilified for his atrocious practice of eugenics, which was a euphemism for mass murder. But it’s amazing how many widely admired people have held similar views of cleansing the undesirables from the human race. Most of them didn’t suggest the use of gas chambers, but their recommendations weren’t exactly humane.

10Helen Keller

As we all know, a childhood illness left Helen Keller blind and deaf in the late 1800s. Without the help of a determined young teacher named Anne Sullivan, she might have been institutionalized.

Keller was a lifelong advocate for the blind and the deaf. Less well known are her strong political views, resulting in FBI surveillance of her for a good portion of her life. She joined the Socialist party in the early 1900s, believed in women’s rights and birth control, supported the NAACP, and helped found the American Civil Liberties Union. The Helen Keller Services for the Blind helps blind and deaf people get educations and jobs.

In her own life, Keller also wanted love. Although she never married, she was once engaged to a man named Peter Fagan. Both Keller’s mother and Anne Sullivan were against the marriage. Supposedly, they believed that Keller wouldn’t be able to take care of a family with her disabilities. At first, Fagan wouldn’t allow Keller to be influenced by her family, but they eventually scared him off.

Keller had a warm, lifelong friendship with Alexander Graham Bell, whose views on eugenics we’ve already discussed. Keller believed in eugenics as well. In her case, it involved people with mental disabilities. When baby John Bollinger was born with various deformities in 1915, surgeon Harry Haiselden refused to operate to save the boy’s life. Instead, he told the boy’s parents that their “defective” child should be allowed to die, saying the infant would “be an imbecile and possibly criminal.” In some cases, Haiselden actively ended the lives of disabled infants. He trumpeted his views, even making a movie (starring himself) to publicize them.

The Chicago Medical Society kicked him out of their organization. Keller expressed her views in a 1915 letter to The New Republic:

“It seems to me that the simplest, wisest thing to do would be to submit cases like that of the malformed idiot baby to a jury of expert physicians. An ordinary jury decides matters of life and death on the evidence of untrained and often prejudiced observers . . . Even if the accused before them is guilty, there is often no way of knowing that . . . He would not become a useful and productive member of society. A mental defective, on the other hand, is almost sure to be a potential criminal. The evidence before a jury of physicians considering the case of an idiot would be exact and scientific. Their findings would be free from the prejudice and inaccuracy of untrained observation. They would act only in cases of true idiocy, where there could be no hope of mental development . . . We must decide between a fine humanity like Dr. Haiselden’s and a cowardly sentimentalism.”

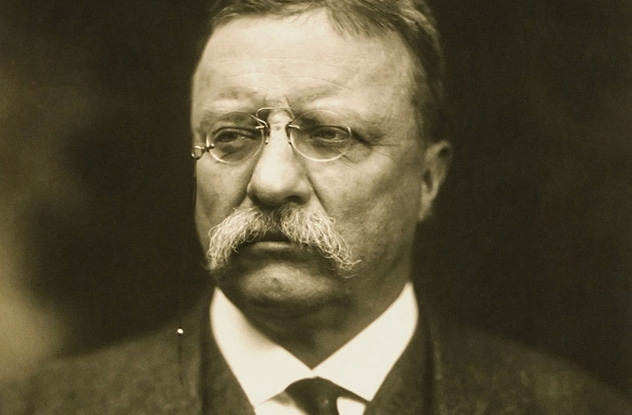

9Theodore Roosevelt

Widely admired during his lifetime, US president Teddy Roosevelt is still highly regarded by many people today. He was the “trust buster,” the man who gave us a “Square Deal,” the conservationist who created the US Forest Service and the National Wildlife Refuge System, and the first American winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906.

He even had the teddy bear named after him because he wouldn’t shoot an old bear after it was tied to a tree. He thought that was unsportsmanlike. But he had no such reservations about eugenics. In a January 3, 1913, letter to Charles Davenport of the Eugenics Record Office, Roosevelt compared human reproduction to stock breeding:

“Society has no business to permit degenerates to reproduce their kind. It is really extraordinary that our people refuse to apply to human beings such elementary knowledge as every successful farmer is obliged to apply to his own stock breeding . . . We fail to understand that such conduct is rational compared to the conduct of a nation which permits unlimited breeding from the worst stocks, physically and morally . . . Some day we will realize that the prime duty—the inescapable duty—of the good citizen of the right type is to leave his or her blood behind him in the world; and that we have no business to permit the perpetuation of citizens of the wrong type.”

Many people associated with the eugenics movement wanted to do away with physically weak individuals. Roosevelt agreed with that in his letter. Yet, he himself was plagued by physical weakness his entire life, even though he promoted an image of being physically robust. He was a sickly child, with severe asthma and myopia. He also had heart problems, became blind in his left eye from a boxing match, and lost the hearing in his left ear.

8Sir Winston Churchill

In 2002, Sir Winston Churchill was voted the greatest Briton of all time by the British public. He was often a polarizing figure, but as one writer put it, “He got the big issues right.”

He was more than just a skilled orator. When almost no one in the US or UK wanted to acknowledge what was happening in Germany under Hitler, Churchill traveled there to get a firsthand look. “It’s an illusion to think he was just a rhetorician, a man who skated over the issues,” said Boris Johnson, the Conservative mayor of London. “He was deeply immersed in all the detail, and all the technicalities. And that helped him to get the right answer.” Churchill also won the Nobel Prize in Literature for his historical works.

Nevertheless, the man who fought Hitler had something in common with him: the belief that eugenics was vital to preserving the purity of a self-defined superior race. “The unnatural and increasingly rapid growth of the Feeble-Minded and Insane classes, coupled as it is with a steady restriction among all the thrifty, energetic and superior stocks, constitutes a national and race danger which it is impossible to exaggerate,” wrote Churchill in a 1910 letter to British prime minister Herbert Asquith.

The Mental Deficiency Act 1913 defined the “mental defectives” who could be put away indefinitely. “Idiots” were so mentally deficient that they couldn’t protect themselves against ordinary physical dangers. “Imbeciles” couldn’t manage their own affairs, although they weren’t as bad as idiots. The “feeble-minded” were better than idiots or imbeciles, but they needed supervision, control, and care to protect others or themselves. A “moral defective” had a permanent mental weakness along with criminal tendencies that couldn’t be controlled with punishment. With minor adjustments, the same definitions applied to children.

Although Churchill didn’t advocate the use of gas chambers, he did believe in the segregation, confinement, and sterilization of these inferior people.

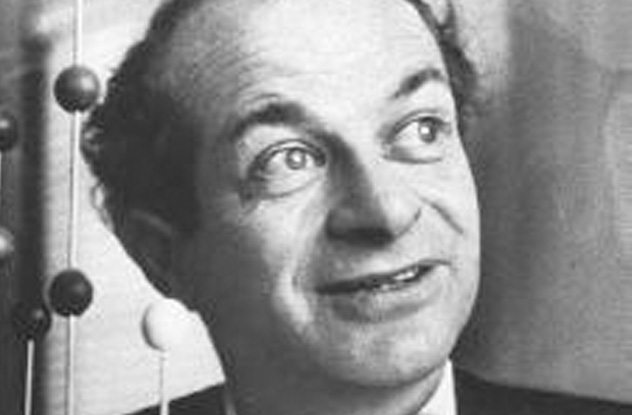

7Linus Pauling

Linus Pauling was a scientist and peace advocate who was so widely admired that he’s the only person to win two unshared Nobel Prizes. The first was for chemistry, and the second was for peace. In all his pursuits, he appeared to have an overriding philosophy to minimize human suffering. He was dedicated to banning the testing of nuclear weapons, arguing that the nuclear fallout was dangerous to human health. Although he was sometimes a controversial figure, he was a tireless advocate for world peace.

He also made a lot of contributions to science, including the observation that sickle-cell anemia was caused by a genetic mutation that deformed the hemoglobin of a blood cell. It was the first time a “molecular disease” had been identified.

Then he combined eugenics with his findings. To reduce human suffering, he believed it was necessary to legally intervene to wipe out the factors that caused genetic diseases. With sickle-cell anemia, he suggested that African Americans be legally required to get tested for the disease. The next step would be to restrict marriage and reproduction for carriers of the disease. He felt that carriers of other genetic diseases, such as fibrocystic disease and phenylketonuria, should be treated the same way.

A few years later, Pauling recommended even more extreme measures to minimize suffering from these diseases. He recommended that carriers have a tattoo or other prominent mark placed on their bodies, perhaps on their foreheads, to identify them. In that way, he figured that carriers of the same disease could avoid getting married. He also felt that if a female carrier became pregnant by a male carrier, the baby should be aborted to reduce the child’s suffering in a preventative manner. He believed that abortion caused less suffering than a hereditary disease.

However, Pauling did not advocate killing a child who had already been born with such a disease. Nor did he believe in forced castration or sterilization.

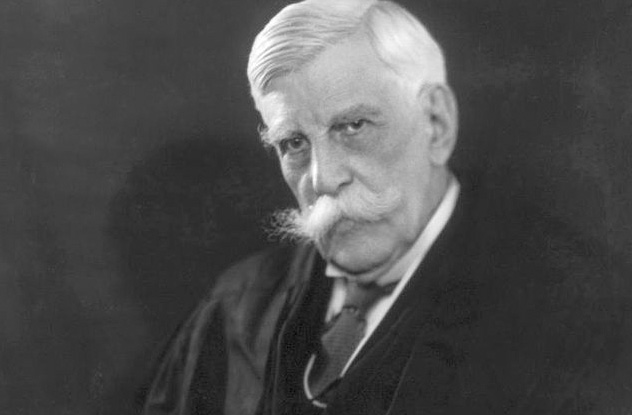

6Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.

As an associate justice of the US Supreme Court for 30 years, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was considered one of the most brilliant jurists of all time. His effect on the law is still felt today, 90 years after his death. Appointed to the court in 1902 by President Teddy Roosevelt, Holmes became known as “The Great Dissenter” because of the supposed wisdom of his dissenting opinions.

Although Holmes was widely admired during his lifetime, there remains at least one dark stain on his career: the 1927 majority opinion he wrote in Buck v. Bell, regarding forced sterilization in the US for undesirables. Using eugenics as the basis for a diagnosis, Charlottesville resident Carrie Buck was deemed unfit to have more children after she became an unwed mother at 17 years old from a rape. It’s believed that her mother was put in a state institution because she was deemed promiscuous, even though she was raped. To make a stronger case to sterilize Carrie, her six-month-old daughter was diagnosed as “abnormal.”

Holmes wrote that Carrie was the “probable potential parent of socially inadequate offspring, likewise afflicted.” He went on to say that “her welfare and that of society will be promoted by her sterilization.”

Holmes also gave the Nazis a line of defense at Nuremberg. To justify their atrocious acts, the Nazis quoted this passage from Holmes’s decision: “It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind . . . Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

That decision paved the way for thousands of women to be forcibly sterilized in the US by upholding Virginia’s sterilization law.

5John Maynard Keynes

In the early 1900s, John Maynard Keynes was considered one of the world’s leading economists. He wrote The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, which looked at how the overall economy performed rather than breaking it down into separate markets. That approach became known as macroeconomics, a branch of study that has been putting students to sleep for almost a century.

At that time, Western governments routinely balanced their budgets. Keynes’s approach was novel because he recommended that governments run deficits when economic growth slows to keep people working. He wanted governments to spend more than they took in during recessions (and then reverse this policy once the economy could bear it).

As a last resort during the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried Keynesian economics to stimulate the US economy. “I came to the conclusion that the present-day problem calls for action both by the Government and by the people, that we suffer primarily from a failure of consumer demand because of [a] lack of buying power,” said Roosevelt in an address to the American people. “Therefore it is up to us to create an economic upturn.”

Keynes got credit for reviving the struggling US economy, making him an economic hero. Others dispute whether Roosevelt’s plan really helped at all. Nevertheless, US fiscal policy was based on Keynesian economics until the 1980s, when President Ronald Reagan used monetary policy to fight rampant inflation.

Keynes also believed in macromanaging the population through eugenics. In his book The Essential Keynes, he wrote: “The time has already come when each country needs a considered national policy about what size of population, whether larger or smaller than at present or the same, is most expedient. And having settled this policy, we must take steps to carry it into operation. The time may arrive a little later when the community as a whole must pay attention to the innate quality as well as to the mere numbers of its future members.”

As director of the Eugenics Society for about seven years, Keynes believed contraception was necessary to limit the growth of the lower classes because they were too “drunken and ignorant” to do it themselves.

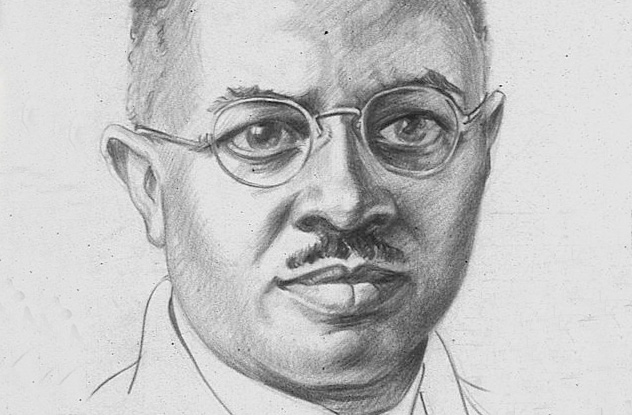

4Edward Franklin Frazier

Edward Franklin Frazier was considered the most important African-American sociologist in the 1900s. Like many of his contemporaries who analyzed the black community, he was a controversial figure. Eventually, he was named the chair of Howard University’s sociology department.

In one of his more contentious findings, he said that African Americans no longer had a link to their African heritage. He believed that they were now culturally American. He was particularly critical of African Americans who saw themselves as middle-class. He thought that they exhibited cultural elitism and led their lives solely for the acquisition of material goods.

Frazier didn’t support the white eugenics model of Nordic superiority, but he did apply a version of eugenics based on class and geography to the black community. In Eugenics and the Race Problem, he wrote, “There is no apparent danger that the best mentally endowed Negroes will debase their intellectual inheritance by mating with feebleminded persons. But there is a danger that the proper institutional controls, which should control the procreation of the colored feebleminded, will be lacking among colored people. In the South where little notice is taken of the colored feebleminded, they are permitted to breed at a rapid rate.”

Frazier believed that black Southerners have undesirable traits that are linked to unregulated reproduction, while the desirable black Northerners, whom he saw as high achievers, got that way through a “socializing process.” He seemed to believe that the environment in the North creates its own natural selection of the best and the brightest. But his references to controlling reproduction in segments of the black population to better the race is typical eugenics language.

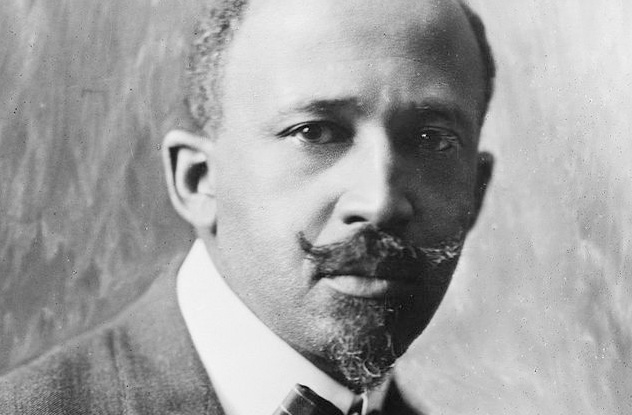

3William Edward Burghardt Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt “W.E.B.” Du Bois was a complicated figure in African-American culture. He often clashed with other black leaders, but his influence was undeniable for many years.

Born in 1868 just after the Civil War, he was the first African American to get a doctorate in history from Harvard University. Shortly afterward, he began to publish insightful papers on the American black community, for which he gained recognition as the first serious scholar of black life in the US.

With his combative approach to fighting racism, Du Bois clashed with the more conservative Booker T. Washington, the most distinguished African-American leader at that time. This caused a rift in the black community, as people chose which type of leadership they wanted.

Du Bois cofounded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), where he edited its monthly magazine, The Crisis. In 1934, Du Bois left the organization in a feud with Walter White, the leader of the NAACP, over the issue of voluntary segregation of the black community. The NAACP preferred to fight for integration, while Du Bois thought the correct course was segregation.

Given his passionate fight for equality, it’s rather surprising that Du Bois believed in eugenics. He didn’t agree with the Nordic eugenics movement, but he did advocate a eugenics approach to the black family. He divided the black community into four groups—from the desirable “Talented Tenth,” whom he saw as educated leaders, to the undesirable “submerged tenth,” whom he described as prostitutes, criminals, and loafers.

Du Bois wanted to promote marriage and reproduction within the Talented Tenth and breed out the submerged tenth. In the Birth Control Review, he said, “The mass of ignorant Negroes still breed carelessly and disastrously, so that the increase among Negroes, even more than the increase among whites, is from that part of the population least intelligent and fit, and least able to rear their children properly.”

2Woodrow Wilson

For over 50 years, Woodrow Wilson has been ranked as one of the top 10 US presidents. According to Franklin D. Roosevelt, “All our great presidents were leaders of thought at times when certain ideas in the life of the nation had to be clarified.” He felt that Wilson was a moral leader who used his position as president to persuade the public and the legislature that he was leading the nation down the right path.

As the 28th US president, Wilson was the nation’s commander-in-chief during World War I. He received a Nobel Peace Prize after the war for negotiating a peace treaty that called for the establishment of the League of Nations, an organization meant to avoid future wars by arbitrating disputes between countries.

Wilson established the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Reserve, getting labor reforms (such as child labor laws) passed and pushing Congress to give women the right to vote. “I do not believe,” said Wilson, “that any man can lead who does not act . . . Under the impulse of a profound sympathy with those whom he leads—a sympathy which is insight—an insight which is of the heart rather than of the intellect.”

His words seem to be at odds with his actions as governor of New Jersey in 1911, when he signed New Jersey’s sterilization bill into law. It was “an act to authorize and provide for the sterilization of feeble-minded (including idiots, imbeciles and morons), epileptics, rapists, certain criminals and other defectives.” It goes on to say that heredity is largely responsible for these “defects,” which was the reason for sterilization without consent.

Wilson suffered a massive stroke in 1919 while he was president. He was paralyzed on his left side, and his vision was impaired. He was confined to bed for 17 months, and his wife and doctor tried to hide his condition. As a result, Mrs. Wilson is considered by some people to be the country’s first female president. But it does raise the question of whether Woodrow Wilson would have been eliminated under some eugenics programs.

1Clarence Darrow

The words of famed defense attorney Clarence Darrow were often poetic, appealing for compassion and tolerance for those who fell short of society’s standards. “I am pleading for the future,” he once said. “I am pleading for a time when hatred and cruelty will not control the hearts of men. When we can learn by reason and judgment and understanding and faith that all life is worth saving, and that mercy is the highest attribute of man.”

By the early 1900s, Darrow was known as the “Attorney for the Damned,” a tip of the hat to his mythical image of always defending the underdogs of society. The man didn’t measure up to the myth.

When Darrow argued that all life was worth saving, he was referring to recent college graduates Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, who had killed 14-year-old Bobby Franks to see if they could commit the perfect crime. According to Darrow, the defendants’ actions were determined by their parents, their wealth, their youth, detective novels, and anything else he could think to blame. As he explained, Leopold and Loeb didn’t kill Franks because they felt any negative emotions toward him. They killed for the experience, like killing a spider.

Darrow has been especially praised for his 1926 article in The American Mercury, in which he argued vehemently against sterilization and the banning of intermarriages for the purpose of eugenics. He even felt that we should keep “morons, idiots, and imbeciles” because we need them to do manual labor for the intelligentsia.

Yet, Darrow displayed a cold cruelty toward disabled children. Ever the champion of the underdog, Darrow went on record as agreeing with Haiselden, the Chicago surgeon Helen Keller had written in response to. “Chloroform unfit children,” Darrow said. “Show them the same mercy that is shown beasts that are no longer fit to live.”