Technology

Technology  Technology

Technology  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff The 10 Unluckiest Days from Around the World

Food

Food 10 Modern Delicacies That Started as Poverty Rations

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Shared TV Universes You’ve Likely Forgotten About

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 of History’s Greatest Pranks & Hoaxes

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 LEGO Facts That Will Toy with Your Mind

10 Juicy Political Scandals From The Early Days Of The USA

Take a close look at early American politics and you’ll find that the country’s always had something of a difficult time of it. Scandals are nothing new when it comes to the government from top to bottom, and some of the early, pre-20th-century scandals are pretty audacious in their scope. From scheming to form a British–Native American alliance that would make Florida a colony again to naked swims in the Potomac, American politicians always seem eager to remind us that they’re as human as the next guy.

Editor’s note: Inflation numbers throughout were estimated here.

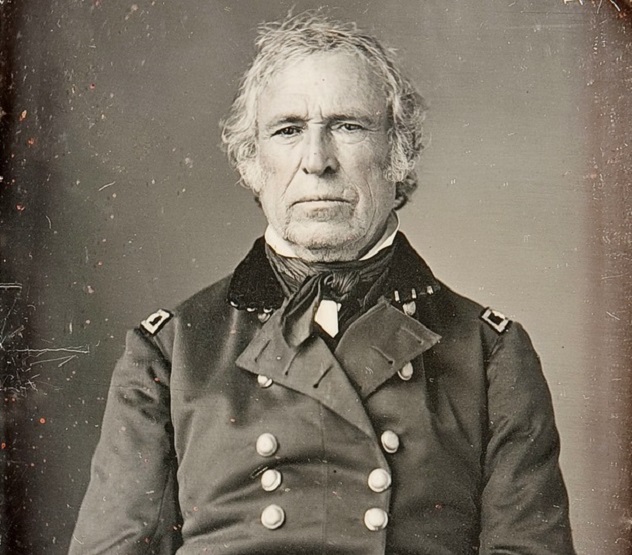

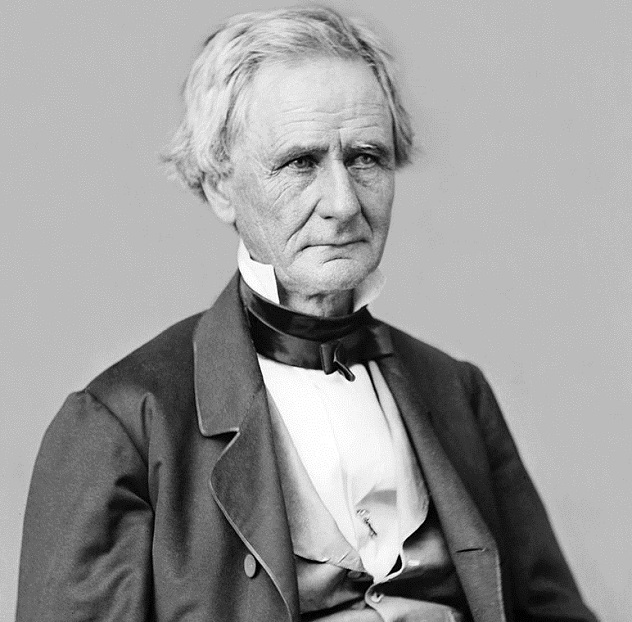

10 The Galphin Affair

While the death of President Zachary Taylor (pictured above) has long been the subject of conspiracy theorists, mainstream historians suspect that the political climate of the time had more to do with the stress that eventually led his death. Taylor was a rare sort who prided himself on his straightforwardness and honesty, and he expected the same of those he put in power. That, of course, wasn’t always the best policy.

The domino-like effects that led to the Galphin Affair started well before Taylor’s presidency, when George Galphin staked a land claim in Georgia and took it as payment for his work with local native tribes. Britain signed the deal, but when Galphin threw his support behind rebel colonists during the Revolutionary War, they didn’t find it necessary to honor a deal signed by a traitor. The state of Georgia got the claim, and, needless to say, they didn’t feel they were bound by the deal that Britain had signed. In 1835, the claim passed to the US government, and the Galphin family lost their land.

By the time Taylor was president, George Galphin was dead but his family hadn’t forgotten. They were paid the amount of the worth of the original claim (about $43,500) but not the interest, which was four times that, at the same time their lawyer, George Crawford, was appointed to Taylor’s cabinet. They kept pushing, and when two other cabinet members approved the payout of the interest (which was nearly $200,000, the equivalent of more than $5 million today), Crawford stood to be paid half of that. Crawford refused to waive his fee, which would have eliminated accusations of corruption in the cabinet. Taylor was faced with replacing members of his cabinet, but the matter had already gone to the Senate, which voted to censure the president for his involvement in the scandal, however unwitting it might have been. But by the time they voted, Taylor was already sick with the illness that would kill him, and his death would bring an end to the matter.

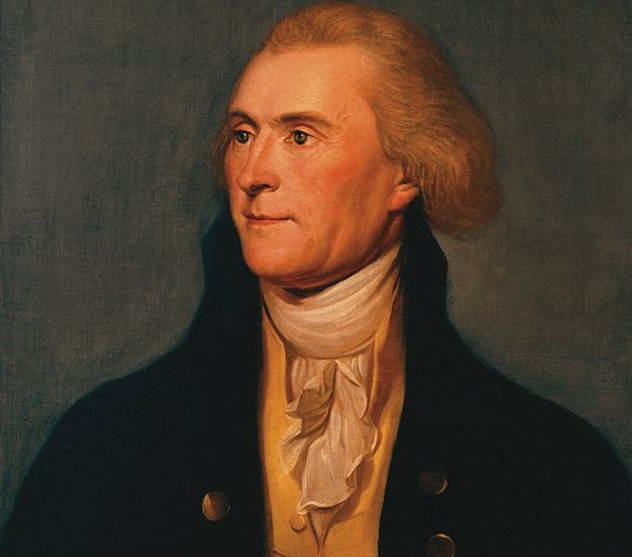

9 James Callender’s Muckraking

After fleeing Scotland in 1793 for being involved in a publication that targeted the British in an unforgiving light, James Callender put his journalistic skills to good use. He was pretty outspoken on a number of things, including the rather undemocratic idea of only electing a president through the electoral college rather than by direct votes; he also thought George Washington was a crook who promoted his own image, and he wasn’t afraid to say it.

Thomas Jefferson recruited him as an ally, supporting him with money as he was working for a Republican paper called The Aurora. He continued his attacks on the Federalists by publishing the scandalous story that Alexander Hamilton was having an affair with a married woman, and he was eventually tried and convicted under the Sedition Acts. Out of jail in 1801, he expected Jefferson to still be there to support him, preferably with a job as Richmond’s postmaster. Jefferson had since washed his hands of the rogue journalist, writing that he was horrified by how far his old friend had gone down the road of muckraking.

Callender, now a bitter alcoholic, fired back and published the first accusations of a scandal that’s still burning pretty brightly today. He accused Jefferson of having a long-term relationship with Sally Hemmings and of fathering her children. Even though he continued to fling mud at political figures in all parties, Jefferson was his new favorite target. There had been rumors about the affair before, but Callender was the one who spread them and gave them credibility. Jefferson’s other children and grandchildren denied the stories, while Jefferson himself adhered to a strict policy of not saying anything on the matter one way or the other.

After Callender received a beating from his former lawyer after threatening to do the same mud-throwing to him, he wrote a letter apologizing for his past actions of dragging the scandalous affairs of political figures into the papers . . . most of them, at least. He later drowned in the James River, and he never apologized for his attacks on his old friend Jefferson.

8 When The Vice President Owned His Wife

All presidential campaigns have their share of digging up the dirt on the competition, but in the case of the 1836 election, there was a whole scandal to be dug up.

Political cartoons had a field day with the domestic situation of Martin Van Buren’s running mate, Kentucky Congressman Richard Johnson (pictured above). Johnson’s wife and the mother of his two daughters was Julia Chinn, and he met her in a rather non-traditional way—he inherited her from his father. Julia was his father’s slave, and she had been raised in the home of his parents. Interracial marriage was technically illegal, so he kept her as his slave, retained his official bachelor title, and made her his common-law wife. On top of that, there were plenty of claims that they had been married in a secret ceremony.

Not only was this 1836, but this was Kentucky. When Johnson was nominated for the vice presidency, it caused quite the outrage. Until then, Julia had run the household with all the rights and privileges of other Southern wives. She ran the household when he was away, and she even oversaw their daughters’ education and Johnson’s business interests. Their daughters both married into white families, Imogene in 1830 and Adeline in 1832.

Election time wasn’t as kind to the family, though. An illustrated election ticket pretty graphically declared, “Carrying the War into Africa: Jinnoowine Johnson” was running on the ticket. The scandal wasn’t over even when Julia died in 1833, since she was never given her freedom and was still technically a slave belonging to her husband. Johnson took two more wives—both Julia’s nieces—and later sold them.

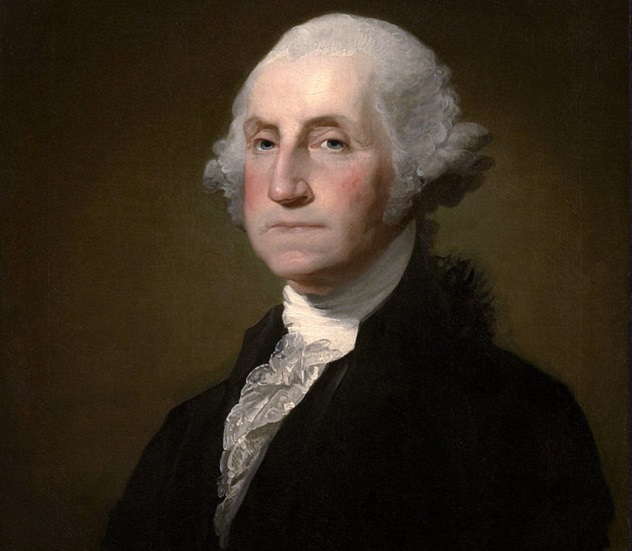

7 The Treaty That Almost Impeached Washington

In 1794, Chief Justice John Jay masterminded the Jay Treaty, which he would be burned in effigy for. The Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation essentially patched up relations with Great Britain, which was seen by many as not only an affront to the new country’s French allies, but an undermining of everything they’d just been fighting for.

Callender’s paper was on the front lines, and Washington was called everything from a dictator to a pawn of the British crown. Republicans pointed to his salary—$25,000 a year, at the time—and introduced a movement in Congress to cut it to $15,000. After all, a rich monarch was what they’d been fighting against, and that’s what Washington seemed to be.

When word of the treaty went public, the same Republicans were at the forefront of a massively angry American population and urging them not to be so enamored with the image of Washington that they forget what he was really doing. With most of the treaty being negotiated behind closed doors, it became something of a poster child for the way the newly installed government was going against the wishes of the people and already looking out for its own interests—which were suddenly very unclear.

When a copy of the treaty was published in full, it was conveniently around the time Fourth of July celebrations were kicking off. They turned into protests and bonfires, burning John Jay in effigy. It was about a month later that Washington signed the treaty in the face of growing contempt. The hate wasn’t directed at the treaty anymore but at the president. For those against the treaty, it turned Washington into a contemptible figure who had done nothing less than spit on the Constitution. Articles started popping up in papers calling for Washington’s impeachment—his signing of the treaty and his salary were considered grounds enough.

Like all big scandals, it gradually died down. Maneuvering people into a position to impeach Washington took longer than the nation’s collective memory had an attention span for, but calls to reassess the balance between the legislative and executive branches of the government continued.

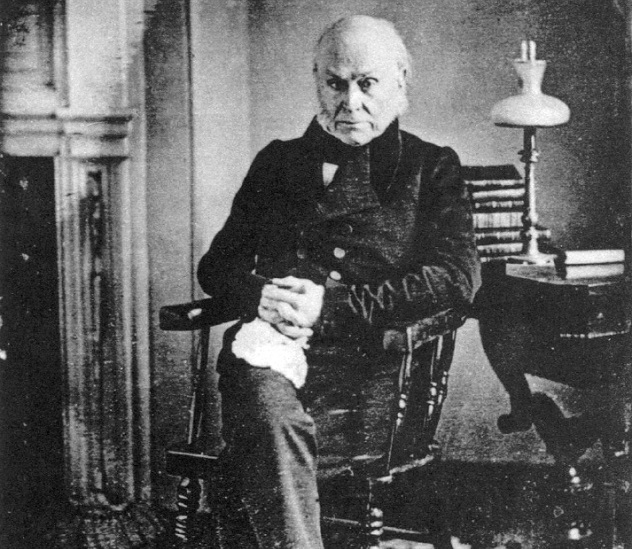

6 Adams’s Shady Deal

The 1824 election had all the scandal you could pack into one election, especially when it came to the outcome. At the end, the winner was John Quincy Adams, but when you look at his opponents, he should have been the underdog. There was war hero Andrew Jackson, previous Secretary of War John Calhoun, William Crawford (who had a huge backing within his party), and Speaker of the House Henry Clay. Adams was the old-school Northern contender, and as the campaign went on, it became pretty clear that Jackson was a favorite to win.

When the electoral votes were tallied, Jackson had the most (99) but still not enough to win. Adams had 84, Crawford 41, and Clay 37. That meant the House needed to meet to pick the winner from the top three candidates, eliminating their speaker, Henry Clay. Clay’s supporters voted for Adams, not only making up the difference, but giving Adams the presidency.

Shady enough, but the outrage really started when Adams installed Clay as his new secretary of state.

Jackson charged that there had been a whole lot of behind-the-scenes maneuvering and the selling of favors to get Adams the presidency, and while Clay always denied those charges, the term “corrupt bargain” was coined from the whole affair. Only a few months into Adams’s term, Jackson had already been nominated and secured to run against him in a rematch, and Jackson used it to his advantage, running on a platform of ousting all the schemers and shady double-dealers that were obviously running the government as it was.

5 Everything About Simon Cameron

On-again off-again Senator Simon Cameron got his first taste of true power when he traded the votes of his Pennsylvania delegation to Abraham Lincoln in exchange for a promise of the ultimate reward—a seat in the cabinet. Lincoln kept his word and made Cameron the secretary of war. Two years later, he’d manage to screw things up so royally that he was appointed as the American ambassador to Russia.

There were a ton of accusations of corruption and scandalous conduct in the War Department under Cameron, so many that when the House of Representatives decided to finally investigate where all the government’s money was going, their findings were compiled into a 1,109-page document. Chief among the accusations was the fact that Cameron didn’t bother shopping around and instead only gave government contracts to his favorites. One of those was recorded as making $20,000 in a single week (the equivalent of around $560,000 today). He was ultimately accused of embezzlement and censured for handing control of public money over to his lieutenant, who then spent $21,000 on a bizarre set of items, including scotch, straw hats, herring, and linen pants.

No one’s really sure how much Cameron benefited from his extravagance and how much of it was just sheer incompetence. Even stranger is that Lincoln continued to sing his praises. Letters from Lincoln to Cameron describe him as an able patriot dedicated to preserving the trust people had put in him. Cameron wasn’t Lincoln’s only problem, either. When it came out that his secretary of the navy, Gideon Welles, was relying completely on a purchasing agent who just happened to be his brother-in-law, questions were raised about how legitimate he was. He was ultimately cleared of any wrongdoing in a Congressional vote, during which Lincoln stood squarely behind him.

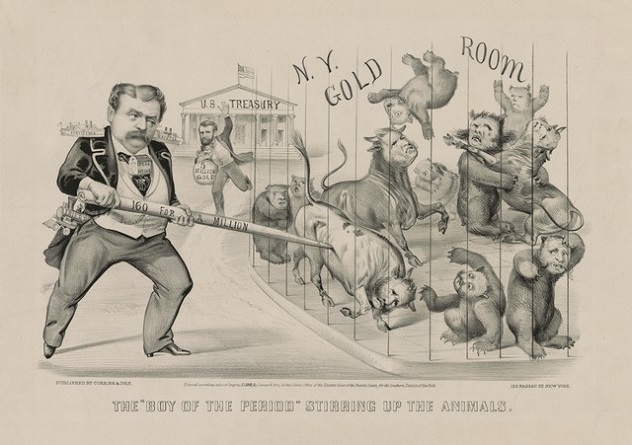

4 The Black Friday Scandal

The US has always had its money problems, and that’s exactly what was at the heart of one of the major scandals that took Ulysses S. Grant from war hero to less-than-popular president.

Jay Gould and Jim Fisk were old friends and financiers who had already worked their magic on some of the country’s capitalist heavy hitters. In the late 1860s, they turned their attention to even bigger fish. In the years after the Civil War, the country was in massive financial trouble, and Grant was following in the steps of his predecessor when it came to trying to dig out of the hole. The government would buy paper dollars from its citizens and replace them with the standard, gold-backed currency.

That’s not what Fisk and Gould wanted. If the government held onto their gold and they bought it, too, the price would rise, and they stood to make a fortune. In order to get the president’s ear, they recruited Grant’s sister’s husband, Abel Rathbone Corbin, to their cause. With Corbin as the linchpin, Gould and Fisk were invited to the same social gatherings as the president, where they helped maneuver another of their own into position, getting Grant to appoint General David Butterfield as an assistant treasurer. Butterfield had already agreed to tip Gould and Fisk off when the government was getting ready to sell its gold, but Grant was suspicious by this point.

After finding proof of the scheme in a letter, Grant sold off $4 million in government gold. It caused a major panic, and the price of gold bottomed out immediately. All the gold that people had been buying up was virtually worthless and unsellable, and those that took out loans to purchase the gold with were ruined. Gould, however, sold early, and avoided ruin. (The cartoon above shows Gould trying to corner the market, while Grant runs from the treasury with the gold he sold.)

The whole thing went before Congress, and Butterfield was removed from office. Those who had lost everything called it Black Friday, and Gould continued to sail through life, owning controlling interests in the Union Pacific Railroad, the Manhattan Elevated Railroad, and the Union Telegraph Company. Fisk was later shot in the head after a dispute over a Broadway showgirl.

3 Everything About Robert Potter

The Texas Historical Association remembers Robert Potter as the secretary of the Texas Navy and signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence, and that’s pretty fitting. If there’s anyone in politics that captured the wild spirit that Texas is still known for, it’s the equally wild Robert Potter.

There are a whole lot of scandals associated with Potter, so we’ll just look at a couple of the best ones. After serving as a naval midshipman and spending a few months studying law after his resignation, Potter decided to run for the position of state representative for the capital of his home state, North Carolina. He lost and issued a challenge to his opponent. Convinced that there was fraud involved somehow, he challenged the opposition to a duel. The challenge was refused, and because politics was done differently at the time, the whole situation descended into a free-for-all fight that ended with one man dead, Potter stabbed with a sword cane, and a few cracked skulls. The whole thing was popularly known as “Hell in Halifax,” and it was so bad that the next year’s election was just canceled. Potter won the next election after that but was then unseated the following election.

Shortly after that, Potter suspected there were a couple people that were being rather too familiar with his wife. These two men were specifically a preacher and his wife’s cousin. Potter attacked, hog-tied, and castrated them both to send a very clear message. Because there are few better kinds of scandals than the ones that involve that kind of rumor and that kind of payback, the term “Potterize” entered into Southern vocabulary as a term for castration. Potter ended up not only serving jail time for it, but he resigned his seat in Congress and headed to Texas when he got out of jail.

2 John Pickering’s Judicial Drunkenness

John Pickering was a hero of the American Revolution, and the first federal justice to lose his job in a pretty epic way.

Even when he sat the bench, the country was very aware that his rulings were going to have a direct impact on their lives. Because he was appointed in 1795 by George Washington, those rulings were going to be forming the basis of law for a fledgling country. The problems were there from the beginning, as he was a raging alcoholic from the get-go. He occasionally just didn’t show up for court, but those days were arguably better than the ones where he showed up ranting, raving, pulling out his hair, and randomly yelling.

And he sat the bench for eight years.

Because it was the state supreme court (of New Hampshire), getting rid of him wasn’t very easy. The problem was that he hadn’t actually committed a crime, even though his conduct was obviously not the best. By the time Thomas Jefferson was president and knew he needed a way to get him out of the courtroom, he had stopped showing up altogether. When he was put on trial in front of the Senate, he (predictably) didn’t show up. While the defense argued for insanity, the prosecution took the point that he wasn’t insane, just perpetually drunk. The trail dragged out for a week before he was finally removed from the bench, and he died two years later after a continued downward spiral.

1 The Senator Who Tried To Sell Florida

William Blount was one of the US’s first senators, and he was one of the signers of the Constitution. You’d think that would seem to imply that he was a patriotic sort, but his actions caused a scandal that made everyone look twice at this new government that had just been set up. They also found themselves trying to figure out where their boundaries were and whether or not it was legal for them to arrest and impeach him based on what they knew.

Blount became a senator for Tennessee right after it was elevated to statehood in 1796. Land rights in the area were still pretty unstable, with Britain, France, and Spain all lurking about in the shadows. Blount, in an attempt to try to stabilize the landscape, threw his lot in with the British and offered to help broker a deal between the British and native tribes, who he hoped would join forces, kick the Spanish out of Florida, and turn it into a British colony. In return, Blount was promised to be the territory’s new colonial governor.

President Adams got word of the conspiracy and turned the proof over to the House of Representatives, who voted to impeach. The Senate did, too, with Blount himself casting the lone “no” vote. He was kicked out of the Senate, and the government was so new that they weren’t entirely sure what to do with him or what kind of charges they could bring. Blount ultimately headed back to Tennessee, was elected to their state senate the next year, and was running the place the year after that, proving (if nothing else) that America loves a good scandal.