Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Historical Ways People Cursed One Another

Whether people call upon the law of the country or take the law into their own hands as a vigilante, the notion of justified revenge is as old as time itself. But what happens when the target cannot be reached by the arm of justice? What do people do then?

In many cases in the past, there was only one thing you could do: appeal to the gods or spirits of your choice and hope they feel like stepping in. As different civilizations developed different ideas of religion and spirituality, so did they generate different ways of bringing ruin upon each other.

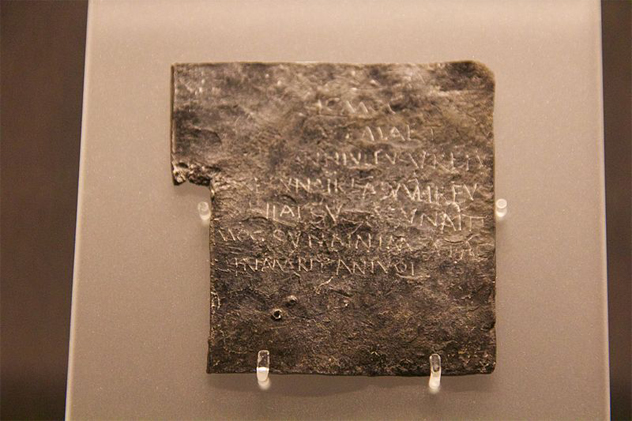

10Roman Curse Tablets

Back in Roman Britain, it was relatively easy to lay a curse on somebody. All you needed was some lead (but if you were all out, wood or stone would do just fine) and something to inscribe on it, and you were good to go. Now all you needed to do was figure out what to write onto this curse tablet of yours.

Curse tablets were easy to write. The aggressor simply had to target a specific person, usually by deed (say, calling down wrath on an unknown thief). Then, they would go into detail about what they would like to happen to the perpetrator. Some of them got pretty creative, such as “ . . . so long as someone, whether slave or free, keeps silent or knows anything about it, he may be accursed in (his) blood, and eyes and every limb and even have all (his) intestines quite eaten away if he has stolen the ring.”

Once done, the aggressor then had to plant the tablet. This was usually done by placing it in an area where a god or goddess would easily come across it. One of the more popular spots to have your curse read by a deity was Bath in England, where shrines were dedicated to the combined Celtic-Roman goddess Sulis-Minerva. Within the waters of the shrine to the goddess, 130 tablets have been recovered, each one laced with a plea to the goddess for ill to befall someone.

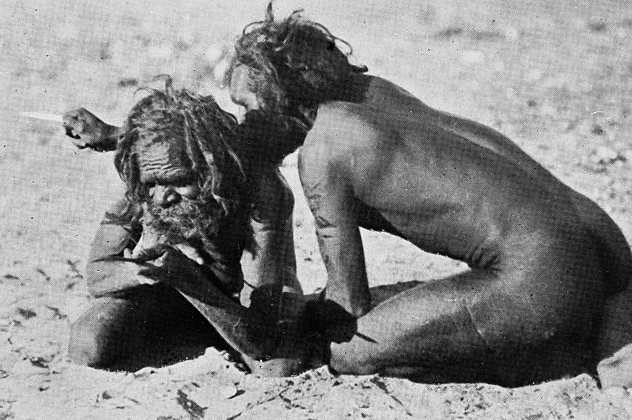

9Bone Pointing

Next time you’re eating spare ribs, make sure you’re careful with how you get rid of the bones afterward—you’re holding an aboriginal way of cursing someone.

The Australian method of choice for calling down spiritual ruin on someone is simply called “bone pointing,” which doesn’t seem too bad at first. The weapon of choice is a sharpened shin bone with human hair attached to the end. On the other end of the hair is a cylinder, also carved from a shin bone. Once the “death bone” has been constructed and imbued with power, it’s ready to use.

Then, a committee comes together to point the bone in the direction of the victim. Once this is done, the effects will not work until the victim has been told they have been cursed, and even then only if they believe in the power of said curse. If both conditions are present, the curse will take effect.

Despite being very rarely practiced in the modern era, there was one case where the bone was pointed at Australian prime minister John Howard in 2004. Thankfully, it did not seem to bring him ruin.

8The Evil Eye

Have you ever noticed a stranger giving you a nasty stare, despite the fact that you’ve done absolutely nothing wrong? In modern days, you would simply assume that the person was a jerk; in the olden times, there was a very real chance that you were being cursed.

Giving the evil eye was a strange procedure. It was usually performed by simply “looking at something wrong”—even if you did not mean to curse anyone. A critical gaze can bring bad health to people and even ruin buildings. It was a deadly curse, for anyone could lay one on you, and you’d have no solid idea as to who did it to you.

The people most susceptible to evil eye attacks were babies and children, due to the fact that they would be praised a lot. Praise was believed to draw the attention of the evil eye, so the best way to counteract the curse was to then spit in the child’s face. Beside making the child feel incredibly confused, it devalued the child as a whole, which would deter any efforts of the evil eye.

7Ushi No Koku Mairi

Word of warning: If your significant other leaves the house around 1:00 AM after you spite them, they might be trying to get their revenge.

The name of this curse is the Ushi no Koku Mairi, which means “Shrine Visit at the Hour of the Ox” in Japanese. The Hour of the Ox is a period of time between 1:00 AM and 3:00 AM—and before you accuse the ox of being greedy, the reason that the “hour” of the ox spans two of them is due to each animal of the zodiac having their own chunk of time to represent them. Given that the ox was usually working by day, they were given the early-morning hours.

To perform the curse, the aggressor first needed an effigy of straw (called a waraningo) based on the person, with some essence of the person upon it (such as blood). Then, during the Hour of the Ox, they would sneak to the nearest Shinto shrine and find the shinboku, a sacred tree thought to be the home of spirits. Once there, the doll would be nailed to the tree, and the curse would be complete.

There are catches, however; it has to be done during the Hour of the Ox, as that was believed to be the hour when evil spirits were on the prowl. It also has to be done in total secrecy, for if someone catches you performing the deed, the curse will backfire—that is, unless all eyewitnesses are taken care of.

6Nidstang

If you ever see someone with a horse’s skull on a pole, be wary of their intentions. Granted, you probably didn’t need us to tell you that, but just in case—they might be trying to perform a nidstang, a Viking curse.

The horse’s head on a pole is known as a “Niding Pole” and is the key to activating the curse. When the practice was more common, the poles reached around 3 meters (9 ft), and they were covered with insults and runes before being stuck into the ground with the skull facing the household of the person who did wrong. The goddess of death, Hela, would then be called upon. But not to harm the person—the intent of the ritual was to annoy the earth spirits.

You had to sink the pole into the ground close enough to the house of the accursed to ruffle the feathers of the earth spirits who lived there. Once this was done, it was believed that the spirits would then take their revenge on the person who occupied their land—the curse’s target. They would make every effort to ruin the person’s life in revenge for the desecrated land, and the curse would be complete.

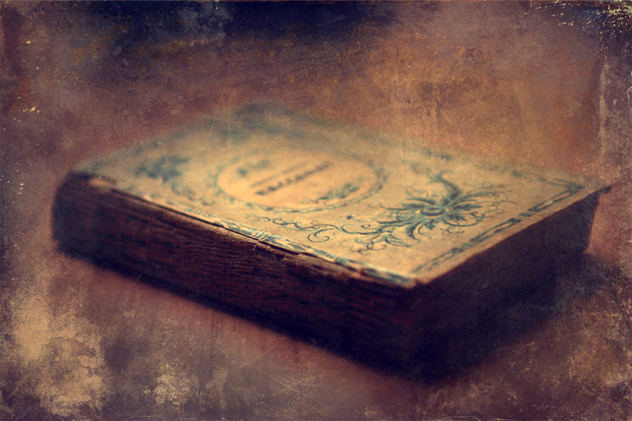

5Book Curses

Back in medieval times, before the printing press was invented, books were a valuable resource. They were a pain to make and highly treasured given their general rarity. The last thing you wanted was someone creeping into your house at night and pilfering your books while you slept. So what could you do? Preemptively curse whoever takes a book without your permission, of course.

Book curses were a protective means against people with eager palms. The curses were usually created by the scribe who wrote the book, who placed it within the colophon of the book (the starting part that mentions publisher details). Curses could call out to any god the writer pleased, and in medieval Europe, they often called to the power of God himself. As far as curses went, scribes didn’t have a one-size-fits-all stamp; they had the freedom of choice to put down any nasty curse they could imagine. Which, after all the effort of hand-writing a whole book, means they spared no mercy.

So how bad could these curses be? Here’s a piece in a book from a Barcelonan monastery, which also fits in a dig against lazy borrowers:

For him that stealeth, or borroweth and returneth not, this book from its owner, let it change into a serpent in his hand and rend him. Let him be struck with palsy, and all his members blasted. Let him languish in pain crying out for mercy, & let there be no surcease to his agony till he sing in dissolution. Let bookworms gnaw his entrails . . . when at last he goeth to his final punishment, let the flames of Hell consume him forever.

It almost makes library fees bearable.

4Catholic Anathemas

One of the more interesting aspects of curses is that people always imagine them being performed by people of dark magic and voodoo. The Catholic faith shows that there are some curses that are utilized by those whose spirituality leans more toward the light.

The modern-day version of the anathema is the Catholic excommunication, which is not something you’d want to receive in the first place. When you look back at some of the anathemas that were written in the Roman Pontifical, however, you get fearsome texts such as this article condemning those who would lead holy nuns astray:

But if anyone shall dare attempt such a thing, let him be accursed (maledictus) at home, and abroad; accursed in the city and in the field; accursed in waking and sleeping; accursed in eating and drinking; accursed in walking and sitting; accursed in his flesh, in his bones, and from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head let him have no soundness.

Some people just aren’t allowed to catch a break.

3Graffiti

The last place you’d think to see curses written would be within a cathedral. A finding by the Norfolk Medieval Graffiti Survey, however, would tell a different story.

The graffiti found in churches in medieval times was very unlike the sort that modern graffiti artists make. Instead of a personal tag to declare presence, graffiti on a cathedral wall would often be prayers and pleas to God.

But that’s not all that was written on the wall of Norwich Cathedral, shown above. In some instances, the researchers studying the graffiti discovered strange, undecipherable writings. Eventually, they worked out that the words had been written upside down—but even then, one of the tags on the walls simply read the family name “Keynsford.”

So was someone of the Keynsford family simply trying their skill at inverse writing? Probably not. What’s more likely is that someone was placing a curse on the Keynsfords. Back then, it was known that inverting something was a sign of ill will on a particular being. Therefore, the reverse name would be the declaration of wishful ruin upon the Keynsford family. To really add evidence to the case, a symbol of the Moon was etched below the inverted writing, which was often used in cursing rituals.

Given that two other inverse names were also found at the cathedral, it’s clear that people were keen to invoke the powers bestowed in churches to bring a curse on someone. At least the victim could definitely see the writing on the wall.

2Nkisi Nkondi

There have been plenty of times when the local justice system wasn’t a strong enough force to help bring peace to communities. While everyone else tried stricter laws and better-trained police forces, one civilization turned to ramming metal nails into vessels of the dead.

Within the Kongo, people constructed small, people-shaped vessels called nkisi. These were created by a spiritual specialist called an nganga who would add items such as cloth and bells to them to help build their spiritual power. They would then be used by the nganga as a focal point to channel spirits within the vessel to perform healing.

This all sounds very nice and peaceful, but the nkisi had a more sinister brother: the nkisi nkondi. Nkondi means “hunter at night,” and it tips you off as to what its role in society was—a protector of the innocent and an icon of wrath against those who perform wrongdoing. If someone fell ill or had misfortune cross them, they would often suspect the work of a witch within their community. To exact revenge upon the evildoer, the victim would approach an nganga and ask for justice against the person they suspected. The nganga would then drive a nail into the nkisi nkondi’s body, which both activated the spirit within and gave it a general idea of what kind of suffering they wanted to inflict upon the evil witch. The spirits took care of the rest.

As well as driving out evil, nkisi nkondi could also be used to seal promises. When an oath was taken, the power of the nkisi nkondi was utilized by ramming a nail into it to activate the spirit. The added protection of the nkisi nkondi was that, should someone break the oath sworn in the presence of the spirit within the nkisi nkondi, said spirit would bring vengeance upon the oath breaker.

1Egyptian Curses

When people think of the word “curse,” their minds likely go to the stories of the curse of Tutankhamun and similar tales. Whether or not you believe in the stories that came out of Egypt, we can still dive into Egyptian history to see if the idea of an Egyptian curse was fact or fantasy.

What you have to realize about Egyptian curses is that people didn’t do them for fun or out of spite; it was believed that the body of a deceased person was very important to the spirit, and that if the body decomposed, the spirit was at risk of dying. The curses weren’t so much a mean spit in the face as they were a means of protection to ensure that the person’s spirit would live on.

Because of this, you won’t find curses in the burial chambers themselves; this is like putting a “keep off the grass” sign in the middle of a vast field. You’ll likely find the curses lining the doorway to the entrance to the tomb, set up to scare looters away so that the body of the deceased—and therefore the spirit—will stay healthy.

So what did people use to adorn the doors of the dead? There’s a nice variety on offer: “I shall seize his neck like that of a goose,” “His heart shall not be content in life,” “His office shall be taken away before his face and it shall be given to a man who is his enemy,” and even “He shall not exist.” It got the point across.

Now that we see how these curses were used by the Egyptians, you can see why the one inscribed above Tutankhamun’s tomb entrance caused a big media stir: “Death Shall Come on Swift Wings to Him Who Disturbs the Peace of the King.” Whether or not the string of catastrophes that came after the tomb was disturbed were the product of curse or coincidence is up to people to decide for themselves, but there’s no denying that the Egyptians at least put in the effort.

S.E. Batt is a freelance writer and author. He enjoys a good keyboard, cats, and tea, even though the three of them never blend well together. You can follow his antics over at @Simon_Batt, or his fiction website, www.sebatt.com.