Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Important Historical Letters Nearly Lost To Time

Before the advent of the Short Messaging Service (SMS), email, and social networking, the most efficient way people who lived far apart could exchange messages was through writing. Most letters are meant for private consumption, so it isn’t surprising that they often reveal astounding secrets when we snoop through them.

10 Fidel Castro To President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Fidel Castro survived the administration of about 10 United States presidents, most of whom would have loved to do away with him. (Some actually tried doing so.) Castro’s first contact with a United States president was, however, amicable.

In 1940, a young student of Colegio de Dolores School in Santiago, Cuba, wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The child, a 12-year-old boy, began the letter with, “My good friend Roosevelt.” He then proceeded to greet the president and tell him he was delighted after hearing on the radio that Roosevelt had been elected for a new term. The child also requested a $10 bill because he had never seen one. This boy was none other than Fidel Castro.

Young Castro wrote that though his English was poor, he was quite smart. As he puts it, “I am a boy, but I think very much.” The letter got to the State Department on November 27, 1940, but never got to Roosevelt, who died without ever knowing who Fidel Castro was.

9 Queen Elizabeth II To President Eisenhower

In 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower became the first United States president to entertain the Queen of England. The queen enjoyed her stay and repaid the kind gesture by inviting the president and his wife over to Balmoral, Scotland, two years later. During the visit, it seemed the president could not get over the taste of the queen’s drop scones off his mind. Five months after the visit, the queen wrote a letter to him that included her own personal recipe for the royal drop scones.

The letter, which was sent on January 24, 1960, was inspired by a photograph of the president barbecuing a quail in a newspaper. The recipe contained helpful hints on how to make the meal—enough to feed 16 people. The queen advised that when prepared for fewer than 16 people, the flour and milk should be reduced. She ended her letter with remarks of how much she and her family enjoyed the president’s visit.

8 Hitler’s Letter Of Leave

On March 1, 1932, Adolf Hitler wrote a letter to the State of Brunswick requesting a leave so he could be allowed to campaign in the forthcoming presidential election for the Reich. The letter was written four days after he officially became a German citizen. Hitler was originally an Austrian citizen and only became a German citizen after he was employed by the state. Hitler went ahead to contest the election and lost out to the incumbent Paul von Hindenburg. However, he was appointed chancellor by Hindenburg the year after.

The letter contained lots of errors. It was predominantly about Hitler’s request for time off until the “end of the time for the selection of the next President of the Reich.” The letter only emerged a few years ago and was expected to sell for more than £5,000 at auction.

7 Albert Einstein To President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Albert Einstein’s 1939 letter to President Franklin Roosevelt is described as one of the most significant letters in recent history. In the letter, Einstein cautioned the president that the Germans may develop a powerful weapon. That letter was later described by Einstein as one of the greatest mistakes of his life. Some historians believe that the letter was likely drafted by Leo Szilard with Einstein only applying his signature to it.

Little is known about the other three letters Einstein sent to President Roosevelt. While the first two were to advise the president and give suggestions, the last one (which was not delivered to the president before he died) was seeking a favor. The final letter, also possibly penned by Szilard, stated that it was Szilard himself who first brought up the concept of nuclear weaponry. The letter contained a request that the president and his cabinet meet personally with Szilard and his fellow scientists to discuss the matter.

6 Mahatma Gandhi To Adolf Hitler

Between 1939 and 1940, Mahatma Gandhi wrote two letters to Adolf Hitler. The more popular of the letters, the “Dear Friend” letter, was written in July 1939. Gandhi wrote that World War II could only be prevented by Adolf Hitler. He appealed to him to follow in his own footsteps of nonviolence, as he had achieved much with his method. The prominent Indian philosopher ended the letter with an apology to Hitler in case his letter caused him any discomfort.

The obscure second letter, however, began with a direct reminder that addressing Hitler as a “friend” was only a formality. In this letter, written after the war had begun in December 1940, Gandhi compared Hitler’s Nazism to the British Imperialism that India had been trying to resist. He also warned Hitler that another world power would improve on his methods and defeat him with his own weapons. He concluded the letter by extending the warning to Mussolini as well.

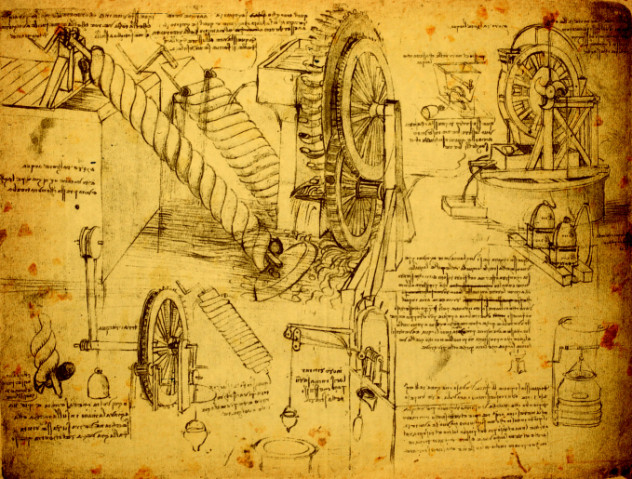

5 Leonardo Da Vinci’s Job Application

Long before Leonardo da Vinci became popular for his paintings, he was just an average Italian with skills—lots of skills. In 1482, at the age of 30, the relatively unknown da Vinci was searching for a job. He wrote directly to the Duke of Milan to apply for a position with him.

Da Vinci listed his skills in the long letter, stating that he could make weapons for ships, armored wagons, catapults, and mangonels. He also pointed out that he could provide the Duke with several methods that he could use to launch assaults and defend himself. Just so that he wouldn’t come across as a man with too much interest in war, he went on to say he could plan bridges, construct buildings, and make sculptures in clay, bronze, and marble. Da Vinci ended the letter by asking the Duke to invite him over for a trial if any of his mentioned skills were doubted.

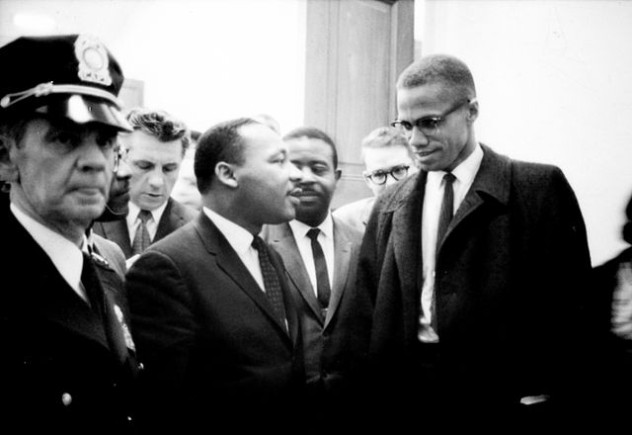

4 Malcolm X To Martin Luther King Jr.

Although Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. fought for the same cause, they were barely friends. While King took a nonviolent approach, Malcolm X went the militant route. Their rivalry got to the point where Malcolm X allegedly referred to King as “Reverend Doctor Chicken-wing.” Malcolm X sent two letters to King, one in 1963 and the other in 1964.

The first letter was to request King’s presence and support in an outdoor rally. In the letter, Malcolm X told King that if President John F. Kennedy, a capitalist, and Russian leader Khrushchev, a communist, could find something in common, then the two of them could also find something in common. Malcolm X also suggested to King that if he could not make it in person, he should send a representative.

The other letter, dated June 30, 1964, was a violent suggestion by Malcolm X. In the letter, he told King of the plight of the people of St. Augustine. He also threatened that if the government did not intervene soon, he might be forced to send some of their brothers to give the Ku Klux Klan “a taste of their own medicine.”

3 Oscar Wilde’s “De Profundis”

The strained relationship between the Marquess of Queensberry and his son, Lord Alfred Douglas, is usually blamed on the relationship Douglas, or “Bosie,” had with Oscar Wilde, who subsequently endured two years in prison after he was convicted of gross indecency. While still in prison at Reading Gaol, Wilde penned a letter to Douglas. The letter was published as an essay and entitled “De Profundis,” which means “from the depths.” It was a reflection of the betrayal of Douglas and Wilde’s regrets.

Wilde stated in the letter that he felt forsaken by Douglas, who published the personal letters and poems Wilde wrote to him. He also wrote that Douglas pushed him to his doom by exploiting his weakness. He blamed himself for not being able to say no to Douglas. He also gave advice to Douglas: “Most people live for love and admiration. But it is by love and admiration that we should live.”

2 Benjamin Franklin To William Strahan

Before America began the fight for its independence, one of her foremost founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin, was close friends with William Strahan, a prominent printer, publisher, and member of the British Parliament. Even after the American Revolutionary War began, the two remained friends until Franklin discovered that Strahan had voted along with his colleagues to label Americans as rebels. In response, Franklin wrote a letter to Strahan.

The letter began on a formal note with Franklin addressing his former friend as “Mr. Strahan.” He blamed Strahan and his fellow Parliament members for the chaos that was running through the United States. He called them murderers and even told Strahan to look at his own hands to see the bloodstains of his relatives. The short letter ended with Franklin’s declaration that their friendship was over and that the both of them were enemies from that moment onward.

1 Grace Bedell To Abraham Lincoln

We once talked about how Abraham Lincoln began keeping his iconic beard after receiving a letter from a young girl named Grace Bedell, who was 11 at the time. In Bedell’s letter dated October 15, 1860, she suggested that Lincoln should grow a beard because his face was thin and he would look better with it. Bedell claimed that women loved beards and would even coax their husbands to vote for him in the elections. Sensing he might be busy, Bedell suggested that Lincoln let any of his daughters reply on his behalf.

Abraham Lincoln personally replied to the missive four days later. He acknowledged getting her letter and told her he didn’t have any daughters—just three sons. He also added that growing a beard might be seen as a senseless affectation. Grace Bedell would later meet the newly elected—and bearded—president when he came to Westfield in 1861.

![Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos] Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/sharonstone-150x150.jpg)