Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Momentous Events That Also Occurred on July 4th

Animals

Animals 10 Times Desperate Animals Asked People for Help… and Got It

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Music Biopics That Actually Got It Right

History

History 10 Momentous Events That Also Occurred on July 4th

Animals

Animals 10 Times Desperate Animals Asked People for Help… and Got It

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

10 Lost Treasures And The Awesome Ways We’re Getting Them Back

If the history of our species was a cheese, it’d be the hole-iest Swiss cheese ever made. So much is missing from our cultural record that piecing our entire history together seems impossible. Over half of our silent films have been wiped out. Enough ancient literature has crumbled into dust that it could fill countless libraries. Languages, ideas, and paintings have all been lost, probably forever.

But not everything that goes missing is irretrievable. Thanks to the awesome magic of science, we’re starting to pull certain things back from the brink. Like John Hammond using ancient traces of dinosaur DNA to build Jurassic Park, we’re recreating ancient treasures we thought we’d lost forever.

10 Mosul’s Lost Artifacts

One of Islamic State’s most horrendous moves has been its practice of blowing up priceless antiquities. In the caliphate’s self-proclaimed capital of Mosul, they’ve been especially destructive. Jihadists have taken hammers to sites that are thousands of years old, trashed the city’s museum, and generally done everything in their power to render Iraqi culture that much poorer.

While the original pieces ISIS looted may be gone forever, European scientists have found a way to help their images live on. By crowdsourcing multiple photos of each object, Chance Coughenour and Matthew Vincent at the EU-funded Initial Training Network for Digital Cultural Heritage have been able to recreate lost artifacts in a digital, 3-D environment. The result is a kind of online museum where anyone with access to the Internet can examine these lost objects from all angles, often in breathtaking detail.

Impressive as this is, it’s just a first step. Speaking with the BBC, Vincent hypothesized a future where 3-D printers could use these images to physically recreate our lost heritage.

Already, the project is exceeding its original goal. Along with treasures from Mosul, Vincent and Coughenour have digitized lost pieces from across Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and earthquake-hit Nepal. The hope is that one day, no rare antique need ever be lost to memory again.

9 Music From Ancient Greece

Until recently, music was one of the most ephemeral art forms. With no recording equipment, the great singers of the ancient world had no choice but to let their words vanish into the ether.

As a result, reading ancient music today can be like trying to understand the Beatles’ back catalog by only studying the lyrics. You get a fraction of what the original audience experienced. However, things are starting to change. Right now, experts are working hard to recreate the music of the ancient world and bring these haunting melodies back to life.

In ancient Greece, literature was accompanied by music. Homer, Sappho, and Sophocles were all originally sung rather than read. This is useful because their written poems and plays now contain hard clues about the rhythm of the music. Using old documents that link words to notation, researchers have been able to determine the pitch and beat of ancient pieces. They’ve also managed to reconstruct ancient instruments. It’s now just a matter of putting this knowledge together.

Some have already taken steps in that direction. In 2013, Dr. David Creese of Newcastle University in the UK constructed his own ancient, eight-string “canon” instrument and uploaded a recording (shown above) of himself singing “Seikilos Epitaph” using tunings recommended by Ptolemy. While the results may sound slightly lame to modern ears, the fact that we know how the song sounds is undoubtedly awesome.

8 Long-Lost Paintings In Color

Many of the world’s greatest paintings have other paintings hidden beneath them. As early as the 1960s, scientists reported that X-ray experiments showed that masters like Rembrandt, van Gogh, and Picasso had reused canvases, painting over earlier works. At first, we could only see traces of these “lost” masterpieces, faint shadows peering out from the past like monochrome ghosts.

That all changed in summer 2015. Using a technique called “macro-X-ray fluorescence (macro-XRF) scanning,” researchers at the Getty Museum, University of Antwerp, and Delft University of Technology were able to partially reconstruct a lost Rembrandt painting in color. Hidden beneath the artist’s An Old Man in a Military Costume, the painting was discovered in 1968, but we didn’t get a proper look at it until 2015. By identifying the chemical composition of different pigments, the macro-XRF scanner allowed scientists to assign colors to areas of the hidden painting, resulting in the distinctive image of a sitting figure.

As this technology is still its infancy, the reconstructed image is far from perfect. In fact, it almost looks like something created in Microsoft Paint in 1999. But as a first step toward recovering these lost paintings, it’s awe-inspiring.

7 The Original Colors Of Ancient Statues

Ask any random person to picture ancient Greece and his mind will immediately fill with epic vistas of white marble. Like picturing T. rex as scaly instead of feathered, this is nice but historically inaccurate. As scientists have known for years, nearly all statues and temples in ancient Greece were painted in bold, garish colors. But we’ve only started using this knowledge recently to reconstruct ancient statues as they were meant to be seen.

Since 2004, the Copenhagen Polychromy Network has been analyzing and studying traces of pigmentation on ancient sculptures. By using techniques like multispectral imaging and X-ray diffraction spectroscopy, they’ve built up a huge amount of data on coloring in ancient statues. A few years ago, they began to bring that data to garish life.

The results are duplicates of ancient statues colored as they would have been 2,500 years ago. In 2014, they even exhibited these multicolored versions beside their white marble originals. As art magazine Hyperallergic saw it, the badly dated coloring “makes them more human and, ironically, brings them closer to us.”

6 The Internet’s Lost History

You’re reading this, so you probably agree that the Internet is one of the greatest inventions in human history. In about 25 years, it has completely revolutionized the way we communicate with one another.

Yet for something so valuable, we’ve been immensely lax about looking after it. The very first web page, created by Tim Berners-Lee, was considered lost forever until recently, and many sites of the 1990s and early 2000s are still missing. While the Web was designed to be disposable, the loss of all these pages still represents a massive hole in our species’ history, akin to losing the Gutenberg Bible.

Luckily, it may not be permanent. For the past few years, digital archaeologist Jim Boulton has been working to find and reconstruct lost pages from the earliest days of the Web. What makes his work different from that of the Internet Archive is that Boulton isn’t content with simply locating missing pages and putting them up on the modern Web. He wants to make them viewable to the public with the same operating systems, hardware, plugins, and browsers for which these ancient sites were originally optimized.

It might sound like a quixotic quest, but Boulton has already had great success, snaring sponsorship from companies like Google and exhibiting across the world. Ultimately, he aims to create an archaeological record of the Web’s early days, one that focuses on the day-to-day sites that shaped our modern Internet.

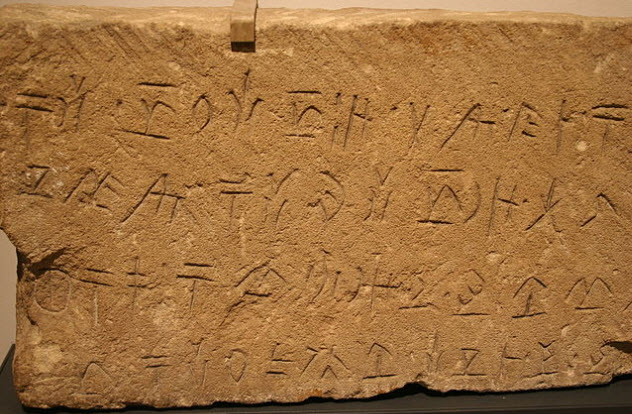

5 Dead Languages

It’s predicted that as many as 90 percent of all languages could be extinct by next century. Already, a huge number of languages have died out. But their extinction may not be permanent. Since 2013, scientists have been working on ways to resurrect the world’s dead languages.

Led by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, a team of scientists have constructed a program that can rebuild protolanguages. Protolanguages are the building blocks of our modern languages, which can be seen when we analyze the etymologies of our modern words. For example, Spanish and Italian carry traces of Latin. By identifying these traces in modern languages, it’s possible to work backward and tease out a common protolanguage. This program does so in record time.

When the software was tested in 2013, it successfully recreated an Austronesian protolanguage spoken 7,000 years ago. As the software advances, we may yet reach the stage when no language ever truly dies.

4 Our Oldest Recorded Sounds

By this point, it’s probably clear that preserving anything for a long time is supremely difficult. This is especially true of sound. From the late 19th century onward, our ancestors made thousands of recordings of everything from jazz music to Yugoslavian folktales to songs sung by backwoods Vermonters. Many of them are now utterly unique, with the conditions that created them gone forever. We probably have less than 20 years before they deteriorate to the point of being unplayable.

If it weren’t for physicist Carl Haber, we’d be facing the destruction of most of our early recorded history. In 2002, Haber heard a program on NPR about severely damaged audio recordings that couldn’t be played to make copies of them. He immediately set about designing a machine that could capture sound by digitally analyzing records.

The result was IRENE. Using cameras, IRENE takes detailed 3-D images of the grooves on old records, which are then translated into sound by a computer program. This means that sounds can be rerecorded without damaging the original source. It’s already saving our aural history.

Thanks to IRENE, we’ve managed to recover items as diverse as the oldest voice recording (a French girl singing a song in 1860) and the only known recording of Alexander Graham Bell’s voice (as heard in the video above). Interviews with people born in the early 19th century, folk songs, and even Woody Guthrie jam sessions have all been saved from obliteration. Now the race is on for IRENE to save as many of our sounds as possible before they’re lost forever.

3 Sounds That Predate Recording Equipment By 165 Million Years

About 165 million years ago, the last Archaboilus musicus chirped for the final time in the steamy forests of what is now China. A species of archaic katydid, an insect similar to a cricket, it once filled the night with its loud, low call. After the last one died, it probably seemed like no one would ever hear that call again. But we were wrong.

Incredibly, scientists recreated the long-forgotten call of Archaboilus musicus in 2013. They were able to do this because of a lucky find and the miracles of modern technology. While working in the fossil-rich region of the Jiulongshan Formation in northeastern China, Beijing scientists stumbled across a perfectly preserved pair of Archaboilus musicus wings.

As an archaic katydid, the insect would have used these wings to produce its call. With the sound-generating structures of the fossilized wings still intact, it was theoretically possible to recreate the exact sound the insect made all those years ago.

With the help of Fernando Montealegre-Zapata, a world expert on biological sounds, the scientists were able to create a program that could mimic the sound that Archaboilus musicus most likely made. As demonstrated in the video above, the insect’s call can be heard again for the first time in 165 million years.

2 Ancient Medicines That Still Work

It’s common knowledge that ancient medicine was useless. Invocations involving a lamb’s eyeballs, sticking leeches on your skin, and wildly waving herbs around are the sorts of madness we associate with old-time doctors. Yet when scientists recreated some of these lost recipes, they discovered something surprising: The medicines worked.

Take this Anglo-Saxon recipe for healing sties from the ninth century. In writing, it sounds like something rejected from Harry Potter: “Take cropleek and garlic, of both equal quantities, pound them well together . . . take wine and bullocks gall, mix with the leek . . . let it stand nine days in the brass vessel.”

When Freya Harrison, a microbiologist at the UK’s University of Nottingham, recreated the potion, she found it was self-sterilizing. What’s more, when tested on mice exposed to the superbug MRSA, it killed 90 percent of the bacteria. That’s about the same percentage killed by modern antibiotics.

This isn’t the only time that ancient medicines have proven to be effective in the modern world. Artemisinin, one of the world’s best antimalarial drugs, was created after scientists discovered it in ancient Chinese medical texts.

1 Ancient Beers

University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Patrick McGovern has perhaps the oddest job in his profession. As the world’s foremost expert on ancient alcoholic drinks, he scours shards of pottery for traces of beer from 7,000 years ago. But McGovern (better known as “Dr. Pat”) doesn’t just isolate these ancient drinks. He chemically analyzes them to determine their ingredients and then recreates these drinks in the modern world.

In partnership with the Dogfish Head Craft Brewery in Delaware, Dr. Pat has brought several long-forgotten beers out of the history books. One such drink was based on beer dregs found in the tomb of King Midas. Another was based on what may have been residue from beer brewing found at an 18,000-year-old site in Wadi Kubbaniya, Egypt. If true, Dr. Pat’s experiments would mark the first time that anyone has tasted this beer since before the invention of the wheel.

These are only a handful of Dr. Pat’s experiments. Throughout his career, he has worked to identify and recreate grog from ancient China, wine from the Etruscan civilization, and beers from many different times and regions. In doing so, he’s taught us more about ourselves, our ancestors, and the evolution of drink, all while having the most rock-and-roll job in the history of archaeology.