Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Insane Ancient Weapons You’ve Never Heard Of

The history of human warfare is as storied as Game of Thrones and even more incestuously brutal. Time and again, the wisdom of the ages has been put to figuring out how to efficiently stab, maim, shoot, and in all other ways kill our enemies, and damn, are we good at it.

But that’s nothing new. In fact, those old guys in your history textbooks were just as imaginative as we are today at pounding foes into the dust. Forget Shakespeare. This is war.

10Greek Steam Cannon

In 214 BC, the Roman Republic laid siege to the Sicilian city of Syracuse in a bid to gain strategic control of the island. General Marcus Claudius Marcellus led a naval fleet of 60 quinqueremes—Roman battleships—across the Strait of Messina in a frontal charge while his second-in-command attacked from the land. But as the noose tightened around the city, the mighty Roman army found itself repelled by an unlikely adversary: Archimedes.

For everything the Romans threw at him, Archimedes was always three steps ahead. Ballistae on the outer walls tore through the advancing cavalry. Seaward, the Claw of Archimedes lifted whole ships out of the water and shattered them in a shower of splinters and screaming slaves. For two years, the siege dragged on, an epic battle of military might versus scientific wit.

During this siege, Archimedes was said to have devised a weapon so devastating that it was able to burn ships to cinder from 150 meters (500 ft) away. All it took was a few drops of water. The device was deceptively simple: a copper tube heated over coals with a hollow clay projectile dropped down the barrel.

When the pipe got hot enough, a tiny bit of water was injected into the tube below the projectile. The water instantly vaporized, blasting the projectile toward advancing ships. On impact, the clay missile exploded, spraying burning chemicals onto the wooden ships.

Even today, Archimedes’s steam cannon is a matter of intense speculation. Mythbusters gave it a bust, but a team at MIT was able to build a working—and highly effective—model using the original description of the cannon.

They calculated that their .45-kilogram (1 lb) metal shell was launched with 1.8 times the kinetic energy of an M2 machine gun firing a .50-caliber round. If they hadn’t shot it directly into a wall of dirt, they guessed that it would have had a range of 1,200 meters (4,000 ft). And they only used half a cup of water.

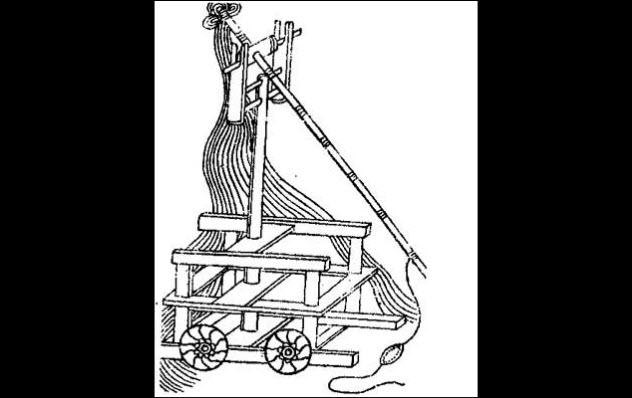

9Whirlwind Catapult

Catapults are the age-old war machines, and like modern rifles, there was a different kind for every purpose. While films have shown us the wall punchers and beast machines used by Greek and Roman armies, the Chinese devised a smaller version that could strike important targets with pinpoint accuracy: the xuanfeng, or whirlwind catapult.

Like a sniper rifle, the whirlwind catapult was a one-shot, one-kill form of attack. They were small enough to be quickly moved around a battlefield, and the entire catapult could be swiveled on its base while someone sighted out a target. This gave them a strategic advantage over heavier catapults and trebuchets which, while much more destructive with a single shot, took time and manpower to maneuver into position.

To add to their deadly accuracy, the Chinese built these whirlwind catapults with two sling ropes and two release pins, keeping the sling pouch perfectly centered in the middle. No other cultures were known to do that.

8Rocket Cats

Nobody had ever heard of rocket cats before 2014. Nobody, that is, except for Franz Helm, the man who invented them. Sometime around AD 1530, the artillery master from Cologne, Germany, was putting together a military guide to siege warfare. Gunpowder was just beginning to have an impact on warfare, which made the book popular. Helm’s manual contained descriptions of nearly every kind of bomb imaginable, all of it colorfully illustrated and grimly outlandish.

Then he added a section advising siege armies to find a cat. Any cat will do, he said, as long as it came from the city you were trying to vanquish. Then tie a bomb to it. In theory, the cat would scamper back to its home and subsequently burn down the entire city. Pigeons were fair game, too.

Whether or not these things actually happened is a question that people are still trying to answer, but the answer is “probably not.” According to Mitch Fraas, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania who had the pleasure of being the first person to translate the text, there isn’t any historical evidence that anybody actually tried to do what Helm suggested. The most likely result of such a scheme, he said, would be setting fire to your own camp.

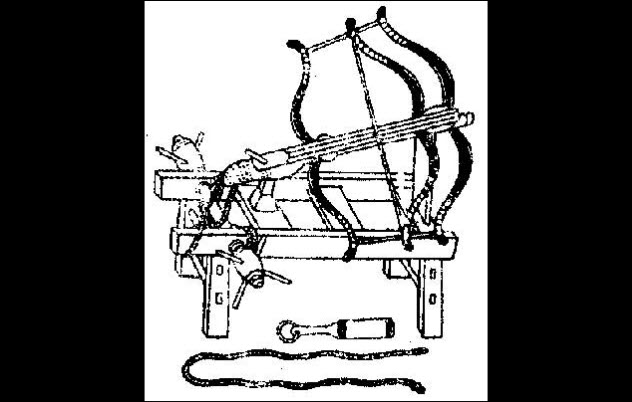

7Triple-Bow Arcuballista

Invented and perfected throughout the height of the Greek and Roman empires, the ballista was basically a giant crossbow mounted on a cart. But the arms of the bow didn’t bend like those of a normal crossbow. Instead, they were solid beams of wood mounted between twisted skeins of rope. When a lever was turned, the ends of the arms rotated toward the back of the ballista and twisted the ropes to create torsion.

It was an immensely powerful weapon, but leave it to the Chinese to say that one bow wasn’t enough. They wanted three. The evolution of the multiple-bow arcuballista was gradual, beginning in the Tang dynasty with a crossbow that used two bows for added power. Records from the period state that this bow could fire an iron bolt up to 1,100 meters (3,500 ft), more than three times the range of other siege crossbows.

At least 200 years later, the invading Mongol forces inspired another arms leap for Chinese arcuballista designers. Sometime during the early Song dynasty, they rolled out the sangong chuangzi nu—the “triple-bow little bed.”

Details of this arcuballista are few and far between. But it’s believed that the Mongolian army, stymied by these powerful defense machines, recruited Chinese engineers to build their own triple-bow behemoths. This eventually turned the tide of war in the Mongols’ favor and led to the rise of the Yuan dynasty.

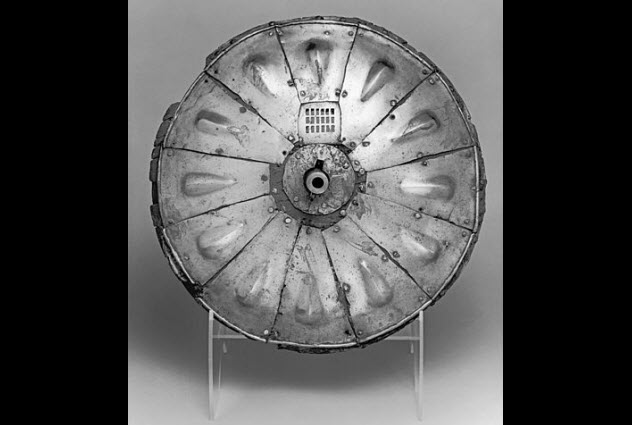

6Gun Shields

Even in the 16th century, when the concept of firearms was still fresher than the pain of a first divorce, people figured out that adding a gun to something gave it at least twice the shooting power. King Henry VIII was especially sold on the idea. In addition to a walking staff made deadly with a spiked morning star and three pistols, his royal armory included 46 gun shields like the one pictured above.

These shields were typically wooden discs with a gun poking through the center, although each was different from the next. Some had iron shielding on the front and others had metal grates above the gun for sighting, but they were all regarded as decorative curiosities more than anything of actual historical interest.

Most of them were appropriated by scattered museums, where they gathered dust in display boxes along with other one-off oddities from the Middle Ages. But the UK’s Victoria and Albert Museum recently took a closer look at their specimen and discovered that gun shields may have been more commonplace than most historians originally believed. So they rounded up as many as they could find and got to studying.

What they found was that several of the gun shields had powder burns from where they’d been used. Some of them also appear to have been designed to lock onto a ship’s gunwales, where they were probably used as an extra layer of shielding as well as a line of antipersonnel fire. In the end, though, it probably made more sense to keep the shields and the guns separate, so the bizarre gun shield fell into obscurity.

5Chinese Flamethrower

As some of the earliest firearms, the Chinese proto-guns were a vast, imaginative arsenal that was unlike anything that had been created to that point. With no prior bias for how a gunpowder-driven weapon should look, Chinese inventors had a blank canvas to create some of the most bizarre guns the world has ever seen.

Fire lances, the first incarnation, emerged sometime in the 10th century. These were spears affixed to bamboo tubes that could shoot a burst of flame and shrapnel up to a few feet away. Some shot lead pellets, others released a burst of poisonous gas, and some fired arrows.

These soon gave way to pure fire tubes as armies ditched the spears in favor of cheap, disposable bamboo guns that only gave one shot but could be mass-produced and fired one after the other. They were often given multiple barrels, leading to nearly endless flavors of death.

From the bowels of this creative mayhem emerged the sky-filling spurting tube. Historians usually call this weapon a flamethrower, but that description doesn’t quite do it justice. Using a low-nitrate form of gunpowder, this weapon could produce continuous bursts of flame for up to five minutes.

But it was the addition of arsenious oxide to the mixture that made it so lethal. The toxic smoke induced vomiting and convulsions. To top it off, the barrel was often packed with razor-sharp porcelain shards. The result was instant laceration followed by a searing bath of poisonous flame. If your Chinese foe didn’t kill you right away, your insides would slowly stop working from the acute arsenic exposure. Eventually, you’d fall into a coma and die.

4Percussion Pistol Whip

On March 17, 1834, Joshua Shaw was granted a patent for the only thing that could have made Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark even better: a riding whip with a pistol hidden in the whip’s handle. What made it particularly useful—and potentially dangerous—was the way it was fired.

Instead of using a trigger like most guns, the pistol had a button in the side of the handle that you could press with your thumb. That allowed a person to hold the whip like they normally would and still have access to the pistol’s trigger. Normally, the trigger was flush with the handle, but when it was cocked, the button would stick out for immediate firing.

At least one of these percussion pistol whips was actually made, although there aren’t any records of them being produced in any kind of numbers. It exists now more as a curiosity than anything else. Its major drawback was that the pistol could only be fired once, but then again, sometimes one shot is all you need.

3Hwacha

China was fiercely protective of its gunpowder weapons during the 14th and 15th centuries. They held the most explosive advance in military technology since the bow and arrow, and they didn’t plan on giving it up without a fight. China imposed strict embargoes on gunpowder exports to Korea especially, leaving Korean engineers to fend for themselves against a seemingly endless onslaught of Japanese invaders.

By the turn of the 16th century, however, Korea had more than stepped up to the gunpowder challenge and was churning out their own war machines, matching any of the spurting tubes defending the Chinese mainland. The Korean tour de force was the hwacha, a multi-rocket launcher that could fire over 100 rockets on a single match. The larger versions used by the king could fire closer to 200. These things were samurai busters, capable of taking down entire formations of densely packed samurai with each salvo.

The hwacha‘s ammunition was called a singijeon, which was basically an exploding arrow. The singijeon‘s fuses were adjusted based on the range of the enemy so that they would explode on impact. When the Japanese invasion began in full force in 1592, Korea already had hundreds of hwachas in operation.

Perhaps the greatest testament to the hwacha‘s power came during the 1593 Battle of Haengju. When Japan mounted an attack on the hilltop fortress with 30,000 troops, Haengju had barely 3,000 soldiers, civilians, and warrior monks in place to defend it. The odds were overwhelming, and the Japanese forces advanced with confidence, unaware that Haengju had one final trick up its sleeve: 40 hwachas mounted on the outer walls.

The Japanese samurai struggled up the hill nine times, only to be repelled again and again by a rain of pure hellfire. More than 10,000 Japanese died before they called off the siege, signaling one of the first major Korean victories in the Japanese invasion.

2Axe Guns

Nearly every culture has made at least one version of a gun-blade combination. Not only do they look cool, they offer a lot of versatility on the battlefield. The bayonets used in the Crimean War and the American Civil War are probably the most famous modern examples, but the trend has been around since the first Chinese fire lances in the 10th century.

Yet somehow, nobody really nailed it like Germany did. Some of the most well-preserved examples of German axe guns currently reside in the Historisches Museum in Dresden and date from the mid- to late 1500s. These ornately carved pieces featured heavy battle axes on the barrels of wheel-lock firearms.

Some could be used as a chopper and a shooter simultaneously, while others were primarily axes that revealed a gun barrel when the axe head was removed. They were likely developed for cavalry, which explains the extended handles on what would otherwise be a pistol.

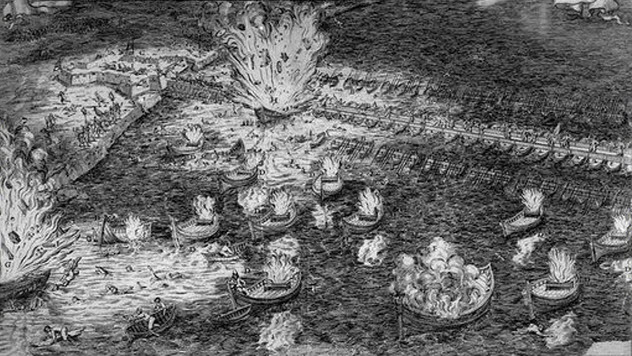

1Hellburners

It was 1584, six long winters into the Eighty Years’ War, and Federigo Giambelli could taste vengeance in the air. Years earlier, he had offered his service as a weapons designer to the Spanish court, but they’d laughed him out of the country. Fuming, he’d moved to Antwerp, where he finally found the opportunity to avenge his bruised Italian ego.

Fresh off a victory against the Ottomans, Spain sent the Duke of Parma to lay siege to Antwerp, which had become the hub of Dutch separatists. The duke hoped to choke the city with a blockade of ships across the River Scheldt.

Antwerp retaliated by sending fire ships—literally, ships on fire—against the blockade. Laughing, the Spanish army pushed them away with pikes until the vessels burned themselves into the river. Still wanting revenge on the Spanish, Giambelli asked the city council for 60 ships, vowing to break the blockade. But the city just gave him two.

Undeterred, Giambelli began building his masterpiece weapons. With each ship, he gutted the hold, built a cement chamber inside with walls 1.5 meters (5 ft) thick, and loaded in 3,000 kilograms (7,000 lb) of gunpowder. He capped it with a marble roof and piled each ship high with “every dangerous missile that could be imagined.”

Finally, he constructed a clockwork mechanism to ignite the whole load at a predetermined time. These two ships became the world’s first remotely detonated time bombs, which he called “hellburners.”

As night approached on April 5, Giambelli sent 32 fire ships ahead of his hellburners to distract the Spaniards. The duke called his men onto the blockade to keep the ships away. But one hellburner grounded too far from the blockade and gently “popped” when its igniter misfired. With the fire ships fizzling out, the second hellburner merely nudged the line of Spanish ships and appeared to be dead in the water. Some of the Spanish soldiers began to laugh.

Then the second hellburner exploded, killing 1,000 men and blowing a 60-meter (200 ft) hole in the blockade. The sky rained cement blocks the size of tombstones. Most importantly, the blast opened the artery to resupply the city.

Shocked, the Dutch didn’t move to bring in the supplies they’d stationed downriver. A few months later, they surrendered to Spain. Giambelli couldn’t have cared less. His war was over because Spain damn well knew his name now.

Eli Nixon is the author of Son of Tesla, the story of a man who would defy a god. Join the fight, and preorder the sequel, Mind of Tesla. Nikola Tesla must die.