Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Beloved But Forgotten Allied Aces From World War I

Flying aircraft in World War I was such a dangerous profession that many airmen even lost their lives during training. These forgotten Allied aces were celebrities during the war who were adored by the public but dreaded by the Germans.

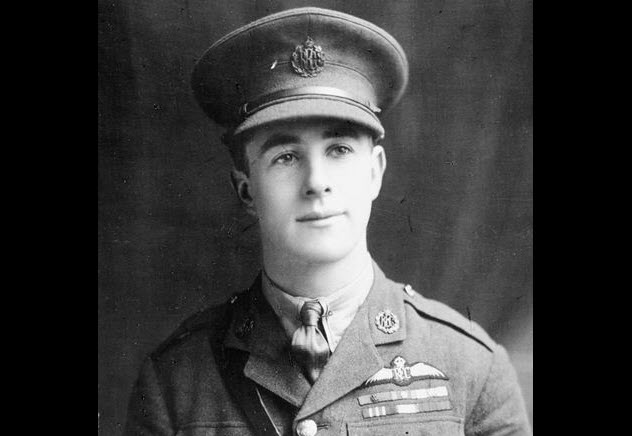

10 Albert Ball

Described by Manfred von Richthofen (aka the Red Baron) as “by far the best English flying man,” Albert Ball was the first celebrity fighter pilot in Britain. He was born in Nottingham on August 14, 1896. After the outbreak of World War I, Ball volunteered for the Notts and Derby Regiment and was made a lieutenant.

He began taking private flying lessons before transferring to the Royal Flying Corps where he gained his pilot’s wings in January 1916. In the months that followed, Ball flew reconnaissance missions with different squadrons.

He recorded his first kill—the pilot of a German reconnaissance aircraft—in May 1916. Soon, Ball was claiming up to three victories per day. On his 20th birthday in August 1916, he was promoted to an acting captain. By the end of that month, he had 17 kills. As people back home in England began hearing stories about Ball’s war heroics, he became a household name. He was usually mobbed in the streets of Nottingham whenever he went home for leave.

In a letter to his parents, Ball said that nothing made him sadder than seeing the enemy’s plane go down, but it was either his life or theirs. On September 26, 1916, he simultaneously received two gallantry awards, the Distinguished Service Order and a bar. By 1917, Ball had 44 confirmed victories and 25 unconfirmed ones. In his last letter to his parents on May 6, Ball admitted that he was beginning to feel like a murderer and hoped the war would end soon because he was tired of killing.

The day after he wrote the letter, Ball got into a dogfight near Douai, France. The enemy pilots included the Red Baron’s brother, Lothar von Richthofen. Ball punctured von Richthofen’s fuel tank during the fight, forcing him to crash-land. But a German fighter pilot also shot down Ball’s plane, killing him. Von Richthofen was credited with Ball’s death, although no one knew for sure who shot him down.

Known for being a “lone wolf,” Ball once took on as many as six enemy aircraft by himself. He often stalked his enemies from below before hitting them. When Ball died, he was Britain’s leading ace. He was posthumously honored with the Victoria Cross by Britain, the Legion of Honor by France, and the Order of St. George (4th class) by Russia.

9 Georges Guynemer

In 1914, Georges Guynemer appeared so frail and weak that French army doctors refused to accept him for service. Using his father’s influence, he was finally allowed to work as an aviation mechanic. In March 1915, he enrolled as a pilot trainee, receiving his pilot’s wings one month later.

Guynemer achieved his first aerial victory on July 19, 1915, when he and his gunner shot down a German Aviatik. Soon afterward, he became a member of the elite Storks squadron.

During World War I, he took part in over 600 aerial combats and was shot down seven times. Hailed as the French Ace of Aces, Guynemer received many letters from admirers, mostly women proposing marriage and schoolchildren asking for autographs.

With his SPAD VII plane (nicknamed “Old Charles”), Guynemer downed as many as four enemy aircraft in one day. Then he armed Old Charles with a single-shot, 37 mm cannon which fired through a hollowed-out propeller shaft to improve its performance and renamed the plane “Magic Machine.” He shot down two German aircraft with Magic Machine.

Guynemer was last seen on September 11, 1917, when he was attacking an Aviatik near Poelcapelle, which was northwest of Ypres, Belgium. A week later, a London newspaper announced that he was missing in action. However, a German newspaper reported that Guynemer had been shot down by Kurt Wissemann of the Jasta 3 Squadron.

For many months, the French populace refused to acknowledge his death. Although his body was never recovered, the frail-looking Guynemer had recorded 54 confirmed kills.

8 Eddie Rickenbacker

Edward Vernon Rickenbacker was born on October 8, 1890, in Columbus, Ohio. By the time America entered the war in 1917, he was a daring race car driver earning about $40,000 a year. Even so, Rickenbacker volunteered for World War I. He wanted to fly but was too old at age 27 for flight training. But his racing credentials earned him a spot as a driver for Colonel William “Billy” Mitchell, whom Rickenbacker pestered until he was permitted to apply for flight training. He claimed to be 25, the age limit for trainees.

After just 17 days as a student pilot, Rickenbacker was commissioned as a lieutenant and assigned to the 94th Aero Squadron. Most of the other squadron members were Ivy League graduates, so they looked down on Rickenbacker because he didn’t have a college degree. But Rickenbacker didn’t care.

He worked to overcome his fear of flying and his dislike of aerobatics. After developing unique fighting techniques, Rickenbacker recorded his first victory on April 29, 1918, a shared credit with Captain James Norman Hall. His first solo victory came eight days later.

Rickenbacker’s technique was to approach the enemy closer than normal before firing his guns. Several times, his guns jammed, leaving him temporarily at the mercy of his enemies. Nonetheless, he survived, scoring five more victories by the end of May. His exploits made headlines in the US, and he gained the respect of his colleagues.

His most memorable exploit was when he took on seven German aircraft, shooting down two before making his getaway. This earned him the French Croix de Guerre and the US Medal of Honor. At the end of the war, Rickenbacker was declared America’s Ace of Aces with 26 victories. Although he never crashed during his days as a fighter pilot, he did survive a pair of crashes in 1941 and 1942. The second crash left him and his fellow passengers adrift on the ocean for more than 20 days. He died at age 83 in Zurich, Switzerland.

7 William Bishop

Born on February 8, 1894, in Owen Sound, Ontario, William Bishop eventually attended the Royal Military College, enlisting during his senior year when World War I erupted. Due to his horseback riding experience, Bishop was ultimately assigned to the Canadian Mounted Rifles in London in June 1915.

But his life changed that July when he saw a plane fly in a nearby field and was inspired to become a pilot. In December 1915, Bishop transferred to the British Royal Flying Corps, receiving his pilot’s license in 1917.

On March 25, 1917, Bishop scored his first dogfight victory when he shot down a German Albatross. In the following two months, Bishop recorded another 21 victories.

He was awarded a Victoria Cross for single-handedly attacking the German aerodrome at Arras on June 2, 1917. He also received the Distinguished Service Order and the Military Cross for his earlier exploits.

In 1918, Bishop became the commander of No. 85 Squadron (nicknamed “the Flying Foxes”), which was posted to the front lines in France. By the end of June 1918, Bishop had recorded over 70 victories, which included shooting down five German aircraft in 12 minutes on June 19. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for this feat.

After World War I, he spent his days making speeches about his wartime adventures. During World War II, Bishop helped to promote the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

Sadly, controversy has trailed Bishop’s legacy. Some historians have charged that the story of the raid that earned him the Victoria Cross was largely false. They have also been unable to confirm some of his combat claims because bombing campaigns during World War II destroyed the relevant documents.

Toward the end of his life, Bishop admitted that some accounts of his exploits were exaggerated. Nonetheless, he is regarded as one of the best aces of World War I. On November 8, 1956, he died in Florida.

6 Rene Fonck

Rene Fonck was the most successful Allied fighter pilot of World War I and the highest-scoring survivor. Born in France on March 27, 1894, he joined the French army in 1914 and attended flying school the following year. He claimed his first dogfight victory on August 6, 1916, when he shot down an enemy aircraft on the Western Front.

During the war, Fonck became an accomplished shooter, although he was not an exceptional pilot. He was especially known for his conservative use of ammunition and his unwillingness to take unnecessary risks when facing the enemy. One of Fonck’s most memorable escapades occurred on May 9, 1918, when he downed six German aircraft over Montdidier, an exploit which he later repeated.

At the end of the war, he was second only to the Red Baron as the most successful fighter pilot. Fonck had 75 confirmed kills, just five short of the Red Baron’s impressive record. However, Fonck claimed that he shot down at least 52 more than the official records stated.

Although he was the French Ace of Aces, his achievements were overshadowed by Guynemer’s heroic status. However, Fonck didn’t seem to be bothered by it, saying that one of his proudest moments was his victory over Captain Wissemann, the man credited with taking down Guynemer. After the war, Fonck worked as a racing and demonstration pilot and then an inspector of fighter aviation with the French Air Force. He died in June 1953 at age 59.

5 James McCudden

Born into a British military family on March 28, 1895, James McCudden followed in the footsteps of his father by joining the Royal Engineers in 1910. He trained as a mechanic and then transferred to the Royal Flying Corps in 1913.

After receiving his pilot’s wings in 1916, McCudden went to France as a sergeant and made his first kill that September. He soon developed a reputation for being a good pilot, a skilled tactician, and a protector of the young pilots under his command. In 1917, he was awarded both a Military Medal when he was noncommissioned and a Military Cross after becoming a commissioned officer.

In December 1917, McCudden attacked eight enemy aircraft with his patrols and personally shot down two of them. The following morning, he encountered four enemy planes and shot down another two. These acts of valor and several others were cited as the main reason that he was awarded the Victoria Cross in April 1918.

Sadly, McCudden died in a flight accident on July 9, 1918, when his aircraft suffered an engine failure. He was credited with 57 confirmed victories and became one of the most decorated combatants of World War I with a Distinguished Service Order and a bar to his Military Cross.

4 Andrew Beauchamp-Proctor

Andrew Beauchamp-Proctor was born on September 4, 1894, in Cape Province, South Africa. World War I broke out while he was studying engineering at the University of Cape Town. He dropped out to join the army, serving as a signaler in the Duke of Edinburgh’s Own Rifles in South-West Africa.

In March 1917, he joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). With a height of only 157 centimeters (5’2″), Beauchamp-Proctor needed to adjust his seat to reach the controls in his aircraft. He was assigned to 84 Squadron in July 1917.

At first, Beauchamp-Proctor appeared to have chosen the wrong profession. He crash-landed his aircraft three times before claiming his first kill on January 3, 1918, when he shot down a German two-seater plane. By May 1918, he had amassed 21 victories, including five in one day on May 19.

Then he shifted his focus and concentrated on shooting down observation balloons. He brought down a record nine balloons in one day on August 9, 1918, securing his reputation as a balloon buster.

Although he was not regarded as a great pilot, Beauchamp-Proctor was still South Africa’s highest-scoring fighter pilot by the end of the war with 54 confirmed victories (38 aircraft and 16 balloons). He brought down more balloons than any other RFC pilot. He was awarded the Military Cross, the Distinguished Service Order, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Victoria Cross.

On June 21, 1921, Beauchamp-Proctor died at age 26 when his plane crashed while he was preparing for an air show at the RAF Hendon. His body was taken to South Africa where he was given a state burial.

3 Robert A. Little

Robert Alexander Little was born on July 19, 1895, in Melbourne, Australia. Although his application was rejected at the Point Cook Military Flying School, Little eventually received his flying certificate and joined the Royal Naval Air Service in England in 1915. He was posted to Dunkirk in June 1916 and assigned to the 8th Naval Squadron in October 1916. The squadron was equipped with Sopwith Pups.

Little’s first aerial victory came on November 1, 1916, with two more victories by the end of the year. In March 1917, Robert shot down nine enemy aircraft and was promoted to a flight lieutenant the next month. The 8th Naval Squadron had their aircraft changed to Sopwith Triplanes and then Sopwith Camels.

Nicknamed “Rikki” by his squadron members after the cobra-killing mongoose in Rudyard Kipling’s stories, Little amassed a stunning 37 victories by August 1917. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross with a bar, the Croix de Guerre, and the Distinguished Service Order (with a bar added in September 1917). He was promoted to a flight commander in January 1918.

Although an excellent shooter, Little was a terrible pilot, frequently crash-landing his plane. In March 1918, he joined the 203 Squadron. Unfortunately, he was fatally injured in the groin at age 22 when he tried to intercept a group of German bombers two months later. With an official tally of 47 victories, he was Australia’s highest-scoring ace in World War I.

2 Raymond Collishaw

In 1893, Raymond Collishaw was born in Nanaimo, British Columbia. He joined the Royal Naval Air Service as a probationary flight sublieutenant in January 1916. His first victory came that October when he shot down future German ace Ludwig Hanstein.

One of his most famous exploits occurred in late 1916 when he was attacked by six German aircraft. They destroyed his instrument panel and goggles with bullets, leaving him partially blind. He escaped but was followed by two enemy aircraft. The first one crashed into the trees; Collishaw shot down the second one.

Barely able to see and without instruments, he landed in a field but soon discovered he was in enemy territory. Immediately, he took off, later landing in a French field near Verdun. He was awarded the Croix de Guerre for this feat.

Collishaw was promoted to the rank of flight commander with the 10 Naval Squadron in 1917. Known as the Black Flight, he and four Canadian pilots worked together, painting their Sopwith Triplanes black and becoming notorious for their escapades on the Ypres front.

They repeatedly challenged the Richthofen Circus and downed some of his unit members. At one point, they might have even fought with the Red Baron himself. When the Black Flight was disbanded in July 1917, Collishaw’s tally stood at 37 downed enemy aircraft.

He then led the 13 Naval Squadron and the 203 Squadron in the Royal Air Force. By the end of the war, Collishaw had 62 victories, with only Billy Bishop and Edward Mannock surpassing his record. Unlike many of his peers, Collishaw stayed with the Royal Air Force after World War I, commanding British forces against the Bolsheviks in Russia and the Allied air forces in North Africa in World War II.

Although touted as the “greatest airman of them all” in a January 1940 edition of the Toronto Star Weekly, Collishaw was not as famous as some of his counterparts. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order with a bar, the Distinguished Service Cross, and the Distinguished Flying Cross. Although he was nominated twice for the Victoria Cross, he never received it.

In 1976, he died at age 82. Following a campaign by some historians, the passenger terminal at Nanaimo Airport was named after Collishaw in 1999.

1 Edward ‘Mick’ Mannock

When World War I broke out in 1914, 27-year-old Edward “Mick” Mannock was working for a telephone company in Turkey. He and his colleagues were imprisoned after Turkey entered the war on Germany’s side. Placed in solitary confinement after an escape attempt, his health slowly deteriorated. The American consulate secured his release in April 1915, and Mannock left Turkey with a deep hatred for the Germans.

After his return to Britain, Mannock joined the Royal Army Medical Corps as a sergeant. He was required to treat enemy prisoners, but his ordeal in Turkey had left him with little compassion for them. Eventually, he was transferred to the Royal Flying Corps and posted to the 40 Squadron at Treizennes in April 1917. At first, Mannock was seen as a coward and a know-it-all by his squadron members. But that changed when he began shooting down German aircraft.

Despite his allegedly deep hatred for the Germans, Mannock sometimes felt pity for them. For example, he once inspected the aircraft of a German he had shot down. He was so disturbed by the sight that he felt like a murderer. Soon, Mannock’s nerves began to fray. He was seen crying and trembling during one of his leaves.

Nonetheless, he returned to war promptly at the end of his leave. Barely one year after his first kill, Mannock’s tally stood at 73, making him the most successful British pilot of World War I. In 1917, he was awarded the Military Cross, to which a bar was later added. The next year, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and two more bars.

On July 26, 1918, Mannock shot down his last German aircraft but made the mistake of flying low to observe it. As a result, he was shot down by German ground fire. He had previously said that his biggest fear was going down in flames without a parachute and burning to death. So he always kept a revolver in his cockpit.

With his worst nightmare realized, it is unknown if Mannock used his revolver that day. But he became the most decorated, highest-scoring British fighter pilot of World War I.