History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

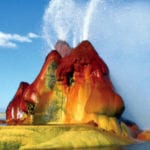

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Natural Mysteries From Australia

Australia’s unique natural world is rich with mysteries that remain unsolved. They are literally everywhere; in the sky, the plant and animal kingdoms, the ocean, strange dimensions, and sightings of things that once were. Science may one day solve some of them, but there are others that will forever remain a part of Australia’s mystique.

10Magnetic Termites

An Australian mystery that still stands—literally—is in the enormous termite hills that act like compasses. For reasons still unknown, termites in the rural Northern Territory construct their monolithic towers in a north-south alignment. The mounds make a creepy sort of sight that begs a second look, almost like giant tombstones that can easily dwarf a tall man. Researchers have a theory about the pole-pointing planks’ purpose. Northern Australia’s sun is a scorcher. In order for a nest to survive in such a hot place, it’s crucial to have some sort of in-house temperature control.

It’s possible that the north-south alignment is the termite version of air conditioning. A mound’s temperature depends on how much of its surface is exposed to sunlight. The sun is at its most unforgiving around noon, but thanks to their unique architecture, at that very hour, these thin structures face the sun with only a single edge. If the unusual magnetic alignment is indeed just a way to keep cool, researchers don’t understand why only this single termite species appears to have developed the ability to sense and use magnetic forces as a survival tool. Indeed, the compass towers are found nowhere else in the world.

9Min Min Lights

The Min Min lights have been called one of Australia’s biggest mysteries. The mischievous glowing orbs are said to tail travelers openly, and some bob after the frightened witnesses for long distances. Locals in Channel Country, Queensland, have known the Min Min lights for a long time: around six decades. One of the first sightings was a light that followed a stockman in 1918, soon after the local Min Min Hotel was lost to a fire. The mystery was named after the place.

Sightings now number in the thousands. Mostly, the orbs are oval, not round, and scoot along 1 meter (3 ft) above the ground. One theory is that these ghost lights are a nighttime version of fata morgana. Simply put, the fata morgana is a spectacular natural phenomenon. Due to factors such as landscape, air temperature, and light refraction, far-off objects, sometimes even mountains, appear as an inverted mirage some distance away over the horizon. However, no explanation has managed to fully demystify the Min Min lights, and they remain a popular local legend and attraction.

8Morning Glory Clouds

Burketown in northern Australia sees a rare meteorological phenomenon each spring: morning glory clouds. Resembling huge, twisted ropes rolling almost endlessly along the sky, not much is understood about how they form. While morning glory clouds do appear in other places around the world, Burketown is the only place where people can “surf” them. Every spring, gliders and even small aircraft pilots gather in big numbers for what they consider the thrill of a lifetime.

A morning glory cloud isn’t the sort to drift slowly; the horizon-stretching bank rolls forward powerfully and creates the lift that cloud-surfers chase. Enthusiasts glide along the front of the cloud, and—depending on how big and active it is—the morning glory can provide a couple of hours of straight surfing in one go. The only real danger to anyone is the possibility of midair collisions. Here, one needs to stay alert. Due to their popularity, every cloud can turn into a veritable highway of crafts converging to enjoy the rare annual event.

7Strange Swapping

Researchers were stunned to discover that kangaroos swap their babies. In 2008, biologists began a project to study the breeding and herd dynamics of the Eastern gray kangaroos. This tendency to adopt was discovered quite by accident. When the tagged animals were checked in 2009, to everybody’s surprise, seven youngsters were snuggling in the wrong mothers’ pouches.

Normally, a female kangaroo will push away a juvenile that’s not hers. Raising another’s young holds no genetic benefit for the foster mother. Yet it happens. What makes it even more unusual is that researchers can’t find any baby kangaroos that switch mothers more than once. Even though they leave their adoptive mother’s pouch on many occasions and thus face plenty of opportunity to climb into a new stranger’s pouch, switching for a second time has never been documented. Once they are adopted, they don’t stray again.

This makes it hard to explain with even the most plausible of theories, such as that a mother kangaroo allows the nearest baby to jump into her pouch when she senses a predator, that kangaroos can’t recognize their family very well, or that they just adopt left and right.

6Devil Facial Tumor Disease

The iconic moody marsupial of Australia, the Tasmanian devil, moves at the heart of a deadly mystery. Tasmanian devils suffer from a cancer so rare, it’s found in only one other species (dogs) and is characterized by the horrifying way it spreads—by mere physical contact. All a devil requires to contract the aggressive cancer is a bite from another infected devil. Unfortunately, they are not the most tolerant of animals, and this quickens the spread of the disease among their population.

Called DFTD (devil facial tumor disease), scientists solved the question of where the cancer comes from; it probably started in Schwann cells. Ironically, Schwann cells are a type of protective tissue for nerve fibers. The mystery of DFTD is why the cancer started in these cells in the first place. Nobody knows.

Once infected, the devil will develop facial lesions and die within months of the first tumor’s appearance. The fight to save the Tasmanian devil from extinction is a tough one. DFTD has already killed off 60 percent of the species, and without an effective vaccine or some other strategy, experts predict that the devils will be gone within two decades.

5Tarantula Town

Near Maningrida, attractive, light-brown tarantulas are doing something odd: About 25,000 of them live in unheard-of proximity to each other, with burrows only a few meters apart. The cluster is thought to be the biggest concentration of tarantulas on Earth, and nearly nothing is known about the species.

Finding so many of them in a small, 10-kilometer (6 mi) strip of valley is just one unexplained secret the diving spider is not telling. What is also unknown is where they keep their babies and whether they are unique to the area. What little is known is that the males are smaller and that the spider can swim and even breathe underwater by bringing along its own air bubbles. Discovered about 10 years ago by local Aborigine children, scientists hope the hairy arachnids—which still need to be named—might possibly possess venom with a valuable pharmaceutical use.

4Pandoravirus

In 2009, a new megavirus emerged in Chile. Researchers failed to find a similarity to any known virus and created an entirely new classification for the newcomer, calling it a “pandoravirus.” Then in 2011, a new breed of pandoravirus was discovered in a Melbourne pond, shaking up the scientific community with its size and secrets. A study of the genetic makeups of the Chilean and Australian varieties revealed that a whopping 93 percent of their genes are unknown to science. This makes the origins of the virus a mystery.

Its size was also a shock. Where most viruses—even complicated ones like AIDS and the flu—only have about 10 genes, the Melbourne virus has roughly 2,000. Nobody knows for certain what the genes are for, how they function, or even why there are so many of them. The rare giant viruses remain significant to science, since they break the barriers of size, habitat (only pandoraviruses live in mud), and how viruses have traditionally been viewed.

3Tree Lobsters

The world’s largest stick insect was once abundant on Lord Howe Island and resembled a large crustacean, earning it the name “tree lobster.” But thanks to shipwrecked rats that preyed on the defenseless insects (they were flightless), there were no more sightings of them after 1920, and the species was presumed extinct.

In 2001, scientists followed an old rumor to a place called Ball’s Pyramid. Situated 25 kilometers away from Lord Howe Island, the ancient volcano seemed an unlikely place to rediscover a lost species. It looked more like a barren spike than a sanctuary. Yet it contained a wonderful mystery: the last population of Lord Howe Island lobsters. Numbering a mere 24 individuals, scientists managed to increase their numbers through captive breeding programs in several zoos.

But how these hand-sized, flightless insects migrated to Ball’s Pyramid remains unknown, and the even bigger question is how they managed to survive there at all. When the colony was found, all the lobsters were sitting in and around a single melaleuca bush from which they didn’t stray, not even when researchers returned years later. There’s yet no answer explaining how they endured for decades in such a limited environment.

2Botanical Dinosaur

The botanical equivalent of stumbling upon a living dinosaur occurred in 1994. The Jurassic survivor was a grove of trees representing the last of their kind: the Wollemi pine. The mystery of the species is the story of its survival. The Wollemi pine saw the dinosaurs come and go, scaled 17 ice ages, and survived other climatic devastation. How, then, did such a tough tree end up with only about 100 individuals, huddled away in a gorge in the Wollemi National Park? That area is prone to severe wildfires, making their continued presence even more astounding.

This rare tree was once widespread, and fossils show that it’s an unchanged species, 200 million years old. When it disappeared from the fossil records about two million years ago, everyone thought the Wollemi pine never survived past that marker. However, the multi-trunk, bubble-barked wonder is still here. While still unproven, the trees’ rarity could have something to do with the Earth’s atmosphere. In ancient times, the CO2 levels were more concentrated and today may be too low for the Wollemi pine to thrive. The incredible durability of the hidden grove remains an enigma.

1Alpha’s Death

In 2003, a satellite tagging project of Australian sharks was following the movements of a great white called Alpha. The 3-meter (9 ft) female gave researchers more than they bargained for. Four months after she was tagged, something ate her. That’s the pervading belief, anyway. Her tag washed ashore, containing information that swept researchers, the Internet community, and even the Smithsonian Channel into a frenzy, looking for a marine monster.

What else could have gulped down such a huge great white shark? Analysis showed that Alpha made an abrupt dive 580 meters (1,900 ft) down before the temperature shot up by more than 30 degrees Celsius (90 °F). Believers in the monster theory claim this proves Alpha was grabbed and swallowed whole, and that the heat came from the killer’s digestive system.

Others don’t feel that the Kraken has risen. For them, the likeliest suspect is another, far larger shark that either consumed Alpha whole or just tore off a chunk—the one that contained the tag. But even with such a logical explanation, the monster hunters are still in the game, citing the possibility that Alpha became the lunch of a prehistoric survivor, the 20-meter (60 ft) extinct Megalodon shark some allege to have seen in Australian waters.