Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

10 Embarrassing Flops From The Crusades

The Crusades are among the most controversial events in European history, but they played a major role in defining Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. United by religious zeal, European soldiers undertook armed pilgrimages to the Middle East to defend Christian civilians and recapture holy sites and relics.

The First Crusade (1096–99) was an almost miraculous success. The Seljuk Turks, the effective and brutal conquerors of the Middle East, were defeated by an equally brutal and fanatical group of Frankish crusaders.

But overall, the crusaders didn’t have a great track record. Even disregarding the moral demur of religious warfare, most of crusading history is filled with embarrassing—and occasionally humorous—flops.

10 The Mega-Pastor Of The First Crusade Runs Away

In 1095, Pope Urban II presided over the Council of Clermont in France and advocated for war against the Turks. Peter the Hermit, a monk from Amiens, France, was roused by the call to war. Enthusiastic, eloquent, and convincing, he became an outspoken advocate for the First Crusade. Consequently, Peter amassed a huge following: He became a medieval mega-pastor, the Billy Graham or Joel Osteen of his day.

But zeal and faith alone don’t make a good soldier. In 1096, Peter led his followers to war a few months before the main crusading armies. Peter’s army was annihilated in Turkey, and he was forced to wait in Constantinople for the rest of the crusaders to arrive.

The First Crusade was a huge, gory mess. In 1098, mega-pastor Peter decided to call it quits, finally realizing that the Crusade may have been a bad idea and his death was probably right around the corner. But as he fled, Peter was captured by the crusaders, prompting him to beg for forgiveness and rejoin the Crusade.

9 Lionheart’s Sister Rejects Saladin’s Brother

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) is known for including two major medieval personalities: Richard the Lionheart, the king of England, and Saladin, the Kurdish sultan of the Ayyubid dynasty. The two monarchs were respected and feared, and European chroniclers portrayed their relationship as courteous, chivalric, and noble.

In 1191, Richard the Lionheart devised a plan to win the war without further bloodshed. Richard offered his sister, Joan, to Saladin’s brother, al-Adil, in marriage without asking Joan’s permission. Saladin agreed. But there was the problem of religion. Joan had no interest in marrying a Muslim, so Richard added a stipulation: Al-Adil needed to convert to Christianity. Saladin and al-Adil refused.

Richard toyed with the idea of trying to substitute his niece for his sister. But Saladin refused to take Richard seriously, and the whole plan disintegrated. The Muslims went on to conquer Jerusalem, and Richard ultimately returned home after brokering a deal with Saladin that allowed a Christian presence in Jerusalem.

8 The Crusade Of Frederick II

Frederick II, the grandson of Frederick Barbarossa, was the Holy Roman emperor, king of Germany, king of Sicily, and duke of Swabia. In 1229, he also proclaimed himself the king of Jerusalem.

Frederick was an intelligent ruler. But he was also unreliable, like a friend who always makes empty promises. The Pope had repeatedly asked Frederick to go on a Crusade because of his political authority and military capability. Repeatedly, Frederick had agreed but failed to keep his word. Ultimately, the Pope excommunicated Frederick.

After he was excommunicated, Frederick decided to finally go on that Crusade he’d been talking about (1228–29). For doing so without papal sanction, his excommunication was reinforced.

Frederick did not care so much about the grand sentiment and purpose of the Crusades. He wanted power and land. Without actually engaging in combat, Frederick negotiated a deal with Malik al-Kamil of Egypt that turned over Jaffa, Bethlehem, Nazareth, and Jerusalem to the Christians. But the treaty also stipulated that the Muslims would retain control of the Temple in Jerusalem and that Jerusalem was to be left undefended. Thus began a 10-year truce between Christians and Muslims.

Frederick then proclaimed himself king of Jerusalem—a title that was universally rejected by the Catholic Church and European nobility. He was excommunicated again.

After the treaty expired, the Muslims quickly retook Jerusalem. This time, it would remain in Muslim control until 1917.

7 The Children’s Crusade

The Crusades were motivated by religious fervor that wasn’t limited to professional fighting forces. But the Catholic Church knew that the Crusades would fall apart if their military forces were not competent in battle. That’s why no one provided official sanction for the ill-fated Children’s Crusade of 1212.

The events of the Children’s Crusade are disputed, but there were two major leaders: Frenchman Stephen of Cloyes and German Nicholas of Cologne. Both were poor, young men.

With a peasantry army of up to 30,000, Stephen felt his mission was to present a series of letters to the king of France to convince him to go on a Crusade. The king’s ultimate response was essentially, “Aw, that’s cute.” It’s likely that no one from Stephen’s group reached the Middle East at all.

Nicholas and his group made it to Genoa. Apparently expecting the seas to open in a grand biblical event, Nicholas was disappointed. Many of the peasants ended up staying in Genoa to work as cheap laborers. Others traveled to Rome, where they were received by the Pope, who told them they should probably go home. Meanwhile, Nicholas’s father was imprisoned and hanged by the angry parents of missing children for encouraging his son’s Crusade.

6 The Many Woes Of Byzantium

The Byzantine Empire was the most powerful Christian state of the Middle Ages, but it was not prepared to deal with the Muslim onslaught from the south and east. As the Byzantines began to lose territory to the Muslims, Alexius I, the emperor at the time, wrote to Pope Urban II to ask for help. This was one of the major sparks of the First Crusade.

When the disorganized and bloodthirsty feudal lords of Western Europe arrived in Constantinople, Alexius realized he may have made a mistake. Unlike the Western Europeans, the Byzantines followed Greek Orthodoxy rather than Roman Catholicism. The two sides did not trust each other because of their religious differences. The crusaders kept the reconquered Byzantine land for themselves, while the Byzantines often left the crusaders to fend for themselves.

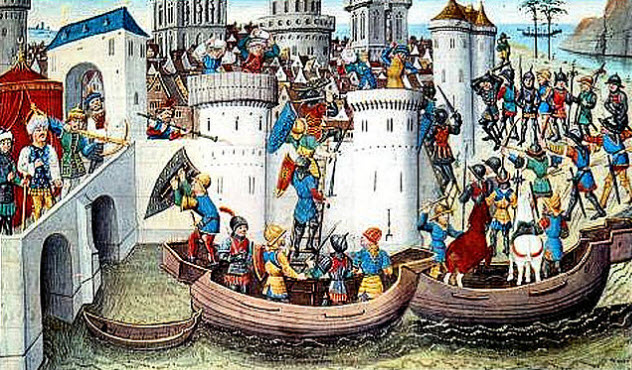

This distrust and betrayal culminated during the Fourth Crusade (1202–04), which was led by the Venetians, French, and Germans. The crusaders needed a way to pay for a Venetian fleet that was meant to invade Egypt. A solution presented itself in the form of Byzantine prince Alexius IV. His uncle, Alexius III, had recently usurped the throne from his father, Isaac II. If the crusaders would help put Alexius IV on the throne, he would finance their Crusade.

The crusaders agreed and attacked Constantinople. The city was taken easily because the Byzantine troops were cowardly. Isaac II and Alexius IV were crowned co-emperors.

But Alexius IV couldn’t keep his promise. No matter how much he taxed his citizens, he could not afford to give the crusaders all the money he owed them. They grew frustrated and began to rationalize a war. Shouldn’t Constantinople be subordinate to the Catholic Church? Weren’t the Byzantines also heretics? Couldn’t a war against them fulfill the requirements of a Crusade?

The crusaders brutally and destructively sacked Constantinople in 1204, installing a Western European emperor. Alexius I’s initial plea for help had backfired horribly.

5 The French King Destroys The Knights Templar

The Knights Templar was a military order dedicated to the cause of the Crusades. They also helped to establish modern banking. The Templars set up a system in which pilgrims and crusaders could make a deposit in Europe and retrieve that deposit in the Middle East, thus making it safe to travel without fear of robbery.

The individual Templar was nominally dedicated to poverty, but the order as a whole soon became immensely wealthy. Enter Philip IV, king of France. When Philip got wind of the Templars’ treasure trove, he decided he wanted it for himself.

Philip convinced Pope Clement V, the only authority to whom the Templars answered, that the Templars were heretical and corrupt. Clement V proved weak and compliant, and despite a lack of evidence for the charges, he caved. The Templars were arrested, their property was seized, and the knights were executed all across Europe.

Jacques de Molay, the grand master of the Knights Templar, was burned at the stake in 1314. Ironically, for all the damage they had done, Clement and Philip died later that year.

4 The Eighth Crusade: Death By Dysentery

By the late 13th century, the idealism surrounding the Crusades was wavering. However, King Louis IX of France was one of the few remaining monarchs who truly believed in the cause. Louis was chivalrous, generous, and honorable—the medieval embodiment of a good Christian king.

In 1248, Louis initiated the Seventh Crusade—yet another attempt to retake Jerusalem, which the Muslims had seized after Frederick II’s treaty had expired. Louis decided to attack Egypt, the center of Muslim power. But the campaign was disastrous: Louis was captured, ransomed, and forced to return to Europe.

Genuinely passionate about the Crusades, Louis decided to fight for Christendom again in 1270. This time, the target was Tunisia. He rationalized that if they could take the ports of Tunisia, fighting in Egypt would be easier.

Things did not go well for Louis when he landed in North Africa. He and a large portion of his army contracted dysentery. Louis died in August. His Crusades were utter disasters despite his devotion and faith. On the bright side, Louis was canonized in 1297.

3 Women’s Scorn Leads To The Crusade Of 1101

Many people who had taken the crusader’s vow in 1096 had been too afraid to actually march to the Middle East. Likewise, many people who had fought in the Crusade had deserted, fearing that the First Crusade was doomed to fail. This included some leading figures.

Europe turned on these deserters and oath breakers when the crusaders actually took Jerusalem. With the crusaders in Jerusalem desperately needing help to defend their hard-won lands, Pope Paschal II threatened to excommunicate anyone who had committed to a Crusade but had not gone.

Throughout Europe, embarrassed and ashamed family members forced the oath breakers to go on the Crusade. One such wife was Adela of Blois, who urged her husband, Stephen, to return to the Middle East. Stephen had been one of the leaders of the First Crusade but had retreated to Europe after a lengthy siege of Antioch.

Under great pressure, Stephen and others participated in the Crusade of 1101. It was an utter failure. The Turks decisively defeated the crusaders at each battle. In 1102, Stephen died at Ramula.

2 Starving Crusaders Eat Saracen Buttocks

During the First Crusade in 1098, the crusaders besieged a city in Syria called Ma’arra. After a month, the Muslim inhabitants surrendered under the condition that the crusaders promise to leave the residents unharmed. The crusaders lied.

They slaughtered the people of Ma’arra. However, the Muslims’ food stores were empty because they had been besieged. On the brink of starvation, the crusaders began to eat the dead. According to historical sources, the crusaders literally cut pieces from the buttocks of the dead Muslims and began to cook them. Adults were boiled in pots. Children were roasted on spits. Unable to fight their hunger any longer, some ate the human flesh uncooked.

Richard the Lionheart was fictionally portrayed as having eaten Muslims in the 15th-century romance Richard Coer de Lyon. In this tale, Richard is craving pork, but his men are unable to find any. Instead, they kill a Muslim and serve Saracen flesh to Richard. Ironically, the flesh tastes just like delicious pork. Richard laughs when he finds out the truth and declares that his army will never starve.

1 The Inadvertent Slaughter Of Jews

The papal-sanctioned targets of the Crusades were the Muslims of the Middle East and the pagans of Europe—groups that had aggressively attacked and killed Christians and conquered holy sites. But the Crusades also inadvertently initiated violent waves of anti-Semitism.

The crusaders rationalized that the Jews were also the enemies of Christianity because they had rejected Jesus and were responsible for his death. Despite papal admonitions of restraint, some crusaders veered way off course and attacked Jewish communities in Europe and the Middle East.

In 1096, the crusaders attacked three prosperous and peaceful Jewish towns in the Rhineland. The Jews were forced to convert to Christianity or die. Some Jews killed their own families rather than convert. After the crusaders took Jerusalem in 1099, the Jewish occupants were made into slaves and forced to clean the city.

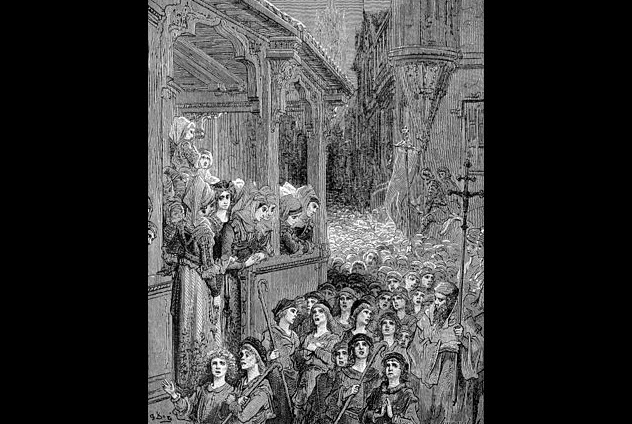

Jews continued to be slaughtered each time a new Crusade was decreed. In 1320, many French citizens created a Crusade that targeted the Jews specifically. Called the Shepherd’s Crusade, the popular uprising against the Jews of France included 40,000 peasants, who were on average only 16 years old. The Crusade was responsible for the destruction of over 100 Jewish communities and led to thousands of Jewish deaths.

The Shepherd’s Crusade was rejected by the European clergy and nobility. The Pope excommunicated everyone who participated, and Christian authorities rounded up the ringleaders and executed them.