Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

10 Little-Known Mysteries From America’s Great Depression

Despite the passage of some eight decades, there are a handful of unsolved murders and disappearances from America’s Great Depression that still attract the public’s attention. Classic cases like the Lindbergh kidnapping, the disappearance of Amelia Earhart, and the Cleveland Torso Murders are the subjects of new articles, books, and documentaries every year. Although those mysteries are the best-known from that time, there were plenty of others that once gripped the country but are no longer remembered today.

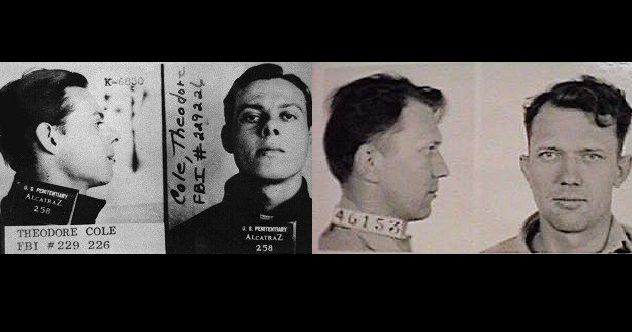

10 The Escape Of Theodore Cole And Ralph Roe

Plenty of people are familiar with the June 1962 escape of inmates John and Clarence Anglin and Frank Morris from the infamous prison on Alcatraz Island. The three men are commonly thought to have been the only inmates who ever successfully escaped the prison. However, two earlier inmates might have beaten Morris and the Anglin brothers by 25 years.

Theodore Cole (left) and Ralph Roe (right) were a pair of 20-something men who had come to Alcatraz in October 1935. They’d both arrived from Oklahoma, although they had never met before. Cole was serving time for kidnapping, and Roe was there for robbing a bank. For several months in late 1937, Cole and Roe worked on sawing a hole through one of the iron-barred windows in the prison’s machine shop. The hole, which they only worked on for a few minutes each day to avoid suspicion, was eventually 22 centimeters (8.5 in) by 46 centimeters (18 in).

On December 16 of that year—coincidentally when the fog was heavy outside—Cole and Roe are believed to have escaped 30 minutes after roll call was conducted at 1:00 PM. The authorities desperately searched the island for the next few days, but they never found a trace of Cole and Roe. Some suspected they might have tried swimming to shore, but others thought a boat might have picked them up. Although the pair was never officially declared dead, prison authorities and the FBI believed the two probably drowned while trying to escape. To date, their bodies have never turned up.

Following their escape, there were reports of Cole and Roe across the American Southwest for several years. Interestingly, a taxi driver in Tulsa claimed to have been shot and robbed by Cole in April 1940. Around the same time, two hitchhikers said they’d ridden with a driver who looked like Roe . . . and had bragged about breaking out of Alcatraz.

9 The Murder Of Allene Lamson

On Memorial Day, 1933, David Lamson received a morning visit from two female acquaintances outside his home in Palo Alto, California. Lamson, a writer and sales manager at Stanford University Press, was raking leaves in his backyard when the two women arrived. Since he was working shirtless, Lamson told his visitors to wait outside a moment as he went inside to put a shirt on.

A few minutes after stepping inside, Lamson bolted out of the house and screamed that his wife had been murdered. The visitors noticed spots of blood on Lamson’s shirt, hands, and face. They then followed him inside, where they found Lamson’s wife, Allene, lying in a tub of blood in the bathroom.

When the authorities arrived, they arrested Lamson on the spot. As he waited in prison, the police searched the house and found a bloody bathrobe and pajamas. In the backyard, they discovered an iron pipe in a small bonfire. After Allene’s autopsy revealed that she had died from a blow to the head, authorities believed the pipe to be the murder weapon. Although Lamson insisted that his wife was killed by intruders, he was charged with Allene’s murder and put on trial. Over the next three years, Lamson would go through four different trials and even spend time on death row before he was released from prison.

The Lamson case became a national sensation, especially after Lamson wrote a best-selling book that criticized America’s prison system and argued for his innocence. His legal team claimed that no blood could be found on the alleged murder weapon. In fact, they said there was no murder weapon at all. According to the defense attorneys, Allene had accidentally fallen and cracked her head open.

At Lamson’s fourth and final trial, the jury failed to reach a verdict and Lamson was let go. Although many doubted his innocence, Lamson lived the rest of his live as a free man, pursuing his dream of becoming a writer and later working for United Airlines.

8 The Murder Of Margaret Martin

Margaret Martin was a shy and intelligent young woman who had studied to become a secretary at the Wilkes-Barre Business College in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Nearly three weeks after graduating with honors, Martin received a phone call from a man looking for a secretary to work at his new insurance agency. On December 17, 1938, Martin left her house to meet the man on a street close to her home. When she failed to return later that evening, her family contacted the police.

Four days after she disappeared, a hunter named Anthony Rezykowski found a burlap bag in a Wyoming County creek. Curious, Rezykowski poked the bag with a stick and was shocked to see a human hand sticking out. The bag turned out to contain the body of Margaret Martin, who was entirely naked and horribly mutilated. According to her autopsy, Martin had been strangled to death. She had also been beaten, stabbed, and tortured.

The police believed Martin had been killed in a nearby sawmill, where the killer might have planned on dismembering and burning her remains. James Kedd, the owner of the mill, told police that a trespasser was on his property the day Martin disappeared, but Kedd had scared the man off after firing a warning shot with his gun.

Despite an extensive investigation, Margaret Martin’s murder was never solved. While her clothes were found burned in Kedd’s sawmill, the bag and rope used to hide her body couldn’t be traced. Several locals reported seeing a woman who looked like Martin getting into a car where she was supposed to meet her job interviewer. Unfortunately, nobody could give a detailed description of the man, and the case soon became cold.

At the time, authorities speculated that the killer was a local man, but a new theory suggests that Martin was the victim of a serial killer who’d drifted into town.

7 The Abduction Of Alice Parsons

Alice Parsons was the 38-year-old wife of William Parsons, a millionaire who raised chickens and squabs on his estate in Long Island, New York. The Parsons kept a Russian housekeeper named Anna Kupryanova and had legally adopted Anna’s son, Roy. With Anna’s help, the Parsons created a recipe for a squab paste, a very popular condiment which inspired the trio to expand their new business.

On the morning of June 9, 1937, William left on business trip to New York City. According to Anna, Alice left with a middle-aged couple a few hours later in order to show off a house she was selling. When William came home at 8:30 PM and saw his wife was still out, he called the police and reported her missing.

While searching Alice’s car for clues, a detective found a ransom note demanding $25,000. The note, which might have been placed in the car hours after the abduction, instructed William to pass the money off at a bus station at 9:00 PM the next night. The letter warned William not to bring along any cops . . . otherwise, Alice would never speak again.

When the appointed time came, William refused to meet the kidnappers because the note had been leaked to the media. He then asked all law enforcement to stay off his property for a short time. This way, the kidnappers wouldn’t have to worry if they decided to bring Alice back. The time passed without any further communication, and neither Alice nor her kidnappers were ever heard from again.

In the next couple of years following Alice Parsons’s abduction, suspicions turned on William and Anna Kupryanova. Some three weeks before she disappeared, Alice had completed her will, leaving her fortune to William, Anna, and Roy. After her disappearance, William moved to California where he married Anna in July 1940. Although the new couple rejected the money bequeathed to them in the will (most of the fortune was split up between Alice’s nieces and nephews), one has to wonder how reliable Anna’s testimony actually was.

6 The Murder Of Henry Frederick Sanborn

On August 5, 1933, four men in Long Island, New York, were looking for berries in a forest when they stumbled upon the odd sight of a shoe sticking out of the ground. When one of the men kicked it, he shook the dirt off the rest of a human leg. The shallow grave contained the body of 44-year-old Henry Frederick Sanborn, a railroad executive who’d disappeared on July 17. Sanborn had been hit on the head and killed by two close-range shots to the back.

The authorities were at a loss to explain Sanborn’s murder. He was a man without any enemies. In fact, he was the kind of friendly guy who liked to have long conversations with complete strangers. Considering Sanborn’s wealth, some wondered whether he’d been robbed, but over $1,000 in cash and checks were found in his pockets.

The day he disappeared, Sanborn left his office at 4:30 PM to check out a house he was interested in buying for himself and his fiancee. Strangely, Sanborn’s fiancee had never heard about his plan to buy a new house until his disappearance. In fact, one of Sanborn’s office workers heard an entirely different story. According to this witness, Sanborn had said he was going to a party, and he’d left with a bag that was missing when his body turned up in the woods.

A week after the body was discovered, a bag resembling Sanborn’s was handed over to the police by a man who’d found it on July 29 in the village of Port Chester. He’d discovered the bag half-open in the grass, containing only a penny. It was marked “N.E.S.,” possibly for one of the pseudonyms Sanborn used while traveling. Detectives proposed that Sanborn might have been involved with another woman, but his fiancee denied the accusation.

However, the day after Sanborn disappeared, an unidentified woman called his office and asked to speak with him. Sanborn’s business associates thought this very strange. After all, no woman had ever called his office before. The identity of this mysterious caller and her relationship with Sanborn has never been explained.

5 The Death Of Mabel Smith Douglass

Mabel Smith Douglass was the first dean and namesake of New Jersey’s Douglass College, which had been called the New Jersey College of Women during her administration. But despite her impressive academic accomplishments, Douglass’s life was an unhappy one. Her husband died in 1916, and her son later committed suicide in 1923. Douglass became so distraught that she suffered a nervous breakdown and spent a year in a mental health facility.

On September 21, 1933, Mabel was vacationing with her family in Lake Placid, New York, when she decided to go out rowing in the lake by herself. However, Douglass never came back, and whether she was alive or dead would remain a mystery for the next 30 years.

On September 15, 1963, scuba divers Richard Niffenegger and Jimmy Rogers noticed a mannequin 32 meters (105 ft) below the surface of Lake Placid. After grabbing the figure’s arm and watching it come off, the divers realized that the “mannequin” was a woman whose body had been extraordinarily well-preserved by the water’s cold temperature and chemical makeup. A rope, which was tied to an anchor, was wrapped around the woman’s neck. Niffenegger decided he would get help, and Rogers waited with the body until his friend came back.

After growing impatient and slightly unnerved by the woman’s ghostly white body, Rogers tried bringing the corpse up to the surface. However, her face disintegrated, and her head and several other body parts fell off by the time she was removed from the water. Using medical records, the authorities determined that the body belonged to Mabel Smith Douglass.

Since Douglass’s daughter had committed suicide in 1948, her body was claimed and buried by Douglass College. Although her death was believed to be an accident (the result of her boat capsizing), others have argued that Douglass might have committed suicide. Given her history of depression, plus the other suicides in her family, this theory doesn’t seem implausible.

4 The Murder Of Pietro ‘Pete’ Panto

Brooklyn’s waterfront was a tough place to earn a living in the 1930s. Longshoremen worked under harsh conditions and had little rights. The workers’ union, the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), was corrupt to its core and connected with the Mafia. In 1939, some radical, left-wing dockworkers began to push for reform. One of the men, an Italian immigrant named Pietro “Pete” Panto, recruited other dockworkers and organized outside meetings. The ILA tried bribing and threatening Panto, but he wouldn’t back down. As the union officials and their mob friends saw it, Panto had to be eliminated.

On the night of July 14, 1939, Panto left for a meeting with two ILA officials. Earlier, Panto had told his brother-in-law that he didn’t trust these guys, and Panto said to call the police if he wasn’t home by 10:00 AM. After getting into a car with one of the officials, Panto was driven off and never seen again.

For the next year and a half, the words “Where is Pete Panto?” were written daily on a tunnel near the Brooklyn waterfront. Despite public support by sympathizers like Richard Wright and other activists, the police were reluctant to answer the question.

In January 1941, Panto’s corpse was found on the banks of a river in Lyndhurst, New Jersey. His limbs and neck had been bound with rope, and his body was tossed into a lime pit. Although nobody was ever convicted for Panto’s murder, it’s believed that he was killed by the mob. Emanuel “Mendy” Weiss (pictured right), a hit man who’d worked with the infamous Murder, Inc., once claimed credit for killing Panto. According to Weiss, Panto was taken to a farm owned by gangster Jimmy Ferraco and strangled after trying to run away.

3 The Murder Of Dorothy Moormeister

On the morning of February 22, 1930, a man coming home from work found the crushed body of 31-year-old Dorothy Moormeister on a rural road near Salt Lake City, Utah. Moormeister had been repeatedly run over by a car. The assault had broken every bone in her body and torn off some of her clothes. The $15,000 worth of jewelry Moormeister had been wearing the previous afternoon was now missing from her body. Her car, which was determined to have been the vehicle that hit her, was found locked and abandoned miles away from the crime scene.

When she left her house the day before, Moormeister had told her maid that she was leaving to meet a friend. She’d said that she would be back later, but she never came home. Witnesses who reported seeing her all gave conflicting statements. Some had seen her alone, others had spotted her with a man, and some claimed she was with two men and one woman. On the road where her body was found, investigators discovered a man’s footprint in the mud.

Despite questioning Moormeister’s friends, the police were unable to gain any new leads. But in September 1964, a man named William Sadler confessed to Texas police that he’d killed Moormeister as part of a contract killing. Sadler, who was in jail for some nonviolent crimes, claimed that he’d murdered Moormeister for $5,000. However, Sadler’s story was eventually deemed unlikely, and he was let go in April 1965.

2 The Murder Of Roland T. Owen

On January 2, 1935, a man using the alias of Robert T. Owen checked into the Hotel President in Kansas City, Missouri. Owen was a strong man, about 180 centimeters (6 ft) tall, and dressed in a black overcoat. He had a noticeable scar on the side of his head which was partially hidden by his hair. The hotel staff thought he seemed uneasy, and the next morning, a maid found him sitting awake in the dark.

Throughout the rest of the day, staff members and other hotel guests heard people swearing and talking loudly in his room. On the second and final morning of Owen’s stay, the hotel’s telephone operator noticed that Owen’s phone was off the hook on three separate occasions. Each time, a bellboy was sent to tell him to hang up the phone.

One of those bellboys found Owen lying drunk and naked on his bed, and when Owen took the phone off the hook for the third time, another boy was sent up to his room. Only when he unlocked the door, the bellboy found blood splattered all over the room. Owen was then discovered in the bathroom, naked and bleeding, covered in cuts and stab wounds.

Amazingly, Owen was still alive, but he would die a few hours later in the hospital. When a detective asked what had happened, Owen refused to explain. In fact, he denied that anyone had been with him. Before he lost consciousness for the last time, Owen claimed that he’d hurt himself by falling against the bathtub.

Investigators suspected that Owen was killed by more than one person. These killers had taken all of his clothes and belongings, including his hotel key. According to the hotel register, Owen was from Los Angeles, but there was no record of anybody by that name who’d lived in the city. Weeks went by, and despite Owen’s post-mortem photo being published in the press, no one ever identified him.

Initially, Owen was going to be buried in a pauper’s grave. However, someone called a local funeral home and offered to pay by mail for Owen to be buried in Memorial Park in Kansas City, Kansas. The mysterious voice said Owen had come to Missouri to meet a girl he was going to marry, but the caller refused to specify anything more. That same day, a florist received an anonymous call asking for roses to be sent to Owen’s funeral. The florist received money by mail, too. In the envelope, he found a card inscribed, “Love forever—Louise.”

Neither the anonymous callers nor Louise were ever identified.

1 The Disappearance Of Wallace D. Fard

Nearly everything about Wallace D. Fard, the founder of what would become the Nation of Islam, is a mystery. His birthday is unknown, and his birthplace has variously been given as New Zealand, Mecca, Afghanistan, or somewhere in the United States. Although Fard preached black supremacy—teaching his followers that white people were the result of a lab experiment that went wrong 6,000 years ago—his ethnicity isn’t clear either. Some believe that he was perhaps white, Arabic, or East Indian. No one even knows his real name. In fact, the FBI estimated that Fard used over 58 different aliases.

In 1930, Fard popped up out of the blue in Detroit, working as a silk salesman in the city’s black neighborhoods. From a mosque in his basement, Fard preached that African Americans were all Muslims and had forgotten their roots. His group of followers, which he called the Allah Temple of Islam, numbered in the hundreds. In 1932, Fard was forced to leave Detroit after a follower named Robert Kariem killed a man as part of a human sacrifice.

After spending a month in Chicago, Fard secretly returned to Detroit, only to get kicked out and sent back to Chicago. By 1934, Fard had been kicked out of Detroit yet again. After being taken to the airport by Elijah Muhammad, the man who’d become his successor, Fard boarded a plane and seemingly fell off the face of the Earth. There are many subsequent legends and rumors about what happened to Fard, including that he spent the rest of his life in California, but nothing is known for certain.

Tristan Shaw runs a blog, Bizarre and Grotesque, where he writes about unsolved mysteries, paranormal phenomena, and other weird and creepy things.