History

History  History

History  Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

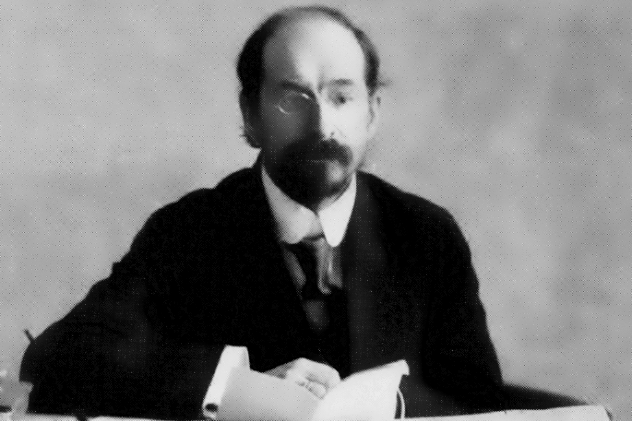

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

10 Failed Attempts To Create State Cults Or Religions

History is full of secular dictators who have erected religious systems to justify their rule, from the Juche cult of the Kim dynasty in North Korea to Papa Doc’s exploitation of Voodoo in Haiti. This is a venerable tradition, stretching back to the imperial cults of Rome, Egypt, and Assyria. But even with the power of the state behind you, not every attempt to set up a novel faith is going to succeed.

10 Theodemocracy

When Mormon prophet Joseph Smith ran for president in 1844, he advanced a new political philosophy in his platform: “I go emphatically, virtuously and humanely, for a theodemocracy, where God and the people hold the power to conduct the affairs of men in righteousness.” The idea of theodemocracy is that the best form of sociopolitical government would be a synthesis of the wills of God and the people. Proponents have argued it was a natural state of affairs both on Earth and in Heaven.

Smith believed that by establishing a republican system that recognized the ultimate authority of God, the political problems of the day would melt away, and liberty, free trade, and the protection of life and property would be maintained. However, while they believed that such a system would bring about “unadulterated freedom,” critics of the church saw the whole idea as undermining democracy, promoting corruption, and seeking to enshrine Smith as a theocratic tyrant.

After the assassination of Smith, the rise of Brigham Young, and the Mormons’ exodus to Utah, there was an attempt to set up a state based on theodemocratic ideals, with ecclesiastical supervision of political and economic matters. However, Young was also quick to claim that, “a theocratic government is . . . a republican government, and differs but little in form from our National, State, and Territorial Governments.”

Attempts to establish a theodemocratic Mormon homeland as either an independent nation or a recognized state of the Union were foiled by the continued opposition of the federal government. By the time Utah was admitted as a state in 1896, little remained of formalized theodemocratic rule.

9 Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

In 1837, thrice-failed civil servant examinee Hong Xiuquan experienced a wave of delirious visions. After failing his exams yet again in 1843, he turned to the Christian book Good Words to Admonish the Age and developed a new interpretation of his experience. He now believed that he had ascended to Heaven and had met with his Heavenly father (Tianfu) and Heavenly elder brother (Tianxiong), Jesus Christ. Hong was told that his mission was to return to Earth and fight the demonic forces of idolatry, popular religion, and the Qing dynasty. The Qing (and earlier Chinese emperors) were to be punished for blasphemously referring to themselves as huangdi, as the word di was reserved for God.

While later Protestant critics lambasted Hong for claiming divinity, in the Taiping worldview, neither Hong nor Jesus Christ were actually divine, though they were the sons of God. Instead, he claimed, “Only the Heavenly Father, the Supreme Lord and Great Shangdi, is the true God. Besides [Him], all others are non-divine.”

Hong Xiuquan’s religious revelation created an ideological blueprint for rebellion against the Qing, a Manchu dynasty against which there was always a simmering Han resentment. The ideology worked to indigenize the Christian faith as a revolutionary movement in opposition to the Confucian framework of the imperial system. It also provided the blueprint for a new state, dubbed the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (Taiping Tianguo).

The theocratic government that Hong established had many progressive features: Opium, wine, tobacco, gambling, slavery, and prostitution were banned. They prohibited foot binding and taught sexual equality, and women held high positions in the government and military. Based on New Testament records of the communal life of early Christians, they banned private property and set up a land redistribution system. However, the system also had totalitarian features, with a highly centralized economy, enforced observation of the Sabbath, and the reading of scripture by military personnel.

At its peak, the Heavenly Kingdom ruled a third of Chinese territory and could have toppled the Qing regime if it had pushed harder. However, their failure to establish a competent new bureaucracy and internal struggles over land reform led to weakness, and the European powers decided to back the weak Qing over the weird Taiping. When the Taiping made moves against the treaty port of Shanghai, the British threw their support behind the Qing and helped to crush the rebellion, ending the Heavenly Kingdom.

8 Legion Of The Archangel Michael

The Romanian fascist group known as the Iron Guard used religious iconography and traditional mysticism as a major current in their ideological thought, along with the more conventional fascist themes of anti-communism, anti-Semitism, and nationalism. They incorporated elements of Orthodox Christianity in order to gain support from the rural population. This included claims of miracles occurring during the rise of the Iron Guard as well as collective prayers, chants, and processions.

The immediate predecessor of the Iron Guard was the Legion of the Archangel Michael, which was established in 1923 by charismatic leader Corneliu Zelea Codreanu (pictured above on the right), who claimed to have been visited by the archangel while imprisoned. An icon of Michael from Codreanu’s prison cell became a sacred icon for the Legion. The movement saw itself as a messianic struggle against hostile foreign forces and “Judeo-Communism,” emphasizing their movement’s focus on religious salvation as opposed to the state worship of Italian fascism or the race worship of National Socialism.

Codreanu believed that the Romanian nation was composed of not only living Romanians, but also the spirits of the dead and those yet to be born. According to his views, “The Nation, the Legionary Movement, the State, and the King together form the country where the earth and its fruits, man and his deeds, God and his secret will are organically fused into the same destiny.”

There was also a pagan element to the ideology, which sought to link the modern Romanian people to the ancient Romans, Dacians, and Thracians and even to establish a cult of the dead. According to Legionary Alexandru Cantacuzino, “The Legion’s concept of death is bound up—after 20 centuries—with the precepts of Zalmoxis, who preached to the Geto-Thracians the cult of the immortality of the soul.”

Repression of the Legion in the late 1930s wiped out most of its original leadership, with Romanian king Carol II ordering the assassination of Codreanu in 1938. Following an internal power struggle, things began to look up for the Legion when Carol II abdicated and General Ion Antonescu (pictured above on the left) proclaimed a national Legionary state, though power was shared with the military. The Legion attempted to cement its cult with the ritual exhumation, pardoning, and reinterment of Legion “martyrs,” but this led to revenge attacks against perceived enemies. In 1941, a failed rebellion by the Legion to seize complete power was suppressed, and the movement was disbanded.

7 Hua Guofeng’s Cult Of Personality

After seizing power in China in 1976 and purging the hated Gang of Four, Hua Guofeng attempted to ride the coattails of Mao Tse-tung’s cult of personality and erect one of his own. He tried to set himself up in the position of a wise leader who would be the best interpreter of Mao’s will. He instituted the policy of the “Two Whatevers,” which stated, “We firmly uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made and we unswervingly adhere to whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave.”

Hua’s propaganda adopted many similar visual cues to his predecessor, including Mao’s iconic swept-back hairstyle. During this period, portraits of Mao and Hua were often hung up side-by-side, but tellingly, Hua’s portrait often needed to have his name written beneath his picture so people would be able to recognize him. He made much of a handwritten note from Mao which read, “With you in charge, I feel at peace.” In one particularly desperate 1977 propaganda poster, he insisted, “The revolution still has a helmsman.”

His personality cult never really got off the ground, and in the third plenary session of the 11th CPC Central Committee in 1978, his faction was outmaneuvered by the supporters of Deng Xiaoping. Guofeng’s personality cult and “leftist errors” were officially rebuked. The Politburo magnanimously allowed Hua to resign from his positions and be ushered out of politics gently, although not before heavily implying that he might be subject to criminal prosecution if he didn’t play ball.

6 Taebong

As the Silla dynasty, which had dominated most of the Korean peninsula under aristocratic rule, began to wane in power in the ninth century, rebel forces arose and formed new state entities, leading to the Later Three Kingdoms period. One of those rebel kingdoms was ruled by former Silla priest Gung Ye, who raised an army of peasants in the provinces of Gangwon, Gyeonggi, and Hwanghae and founded his own personal kingdom.

According to records, Gung Ye was a Silla prince but was condemned to death by the king when an oracle claimed that he would one day bring ruin to the kingdom. He was saved by his nanny, who unfortunately injured the prince’s eye in their escape. He grew up as a Buddhist monk before joining the growing rebellions in 891, eventually accruing enough personal power, loyal soldiers, and connections to declare his own kingdom.

He first named his kingdom Later Goguryeo (after an earlier state), then renamed it Mujin, and finally dubbed it Taebong. Later historians would analyze these name changes as linguistic attempts to establish his kingdom as a new entity as expressed through esoteric Chinese Five Elements Co-existence Theory, reflecting his worldview.

Initially, Gung Ye sought to break down the rigid caste system that had prevailed under the Silla and to build an ideal, prosperous society without discrimination. However, he soon became a tyrant and developed heterodox religious views, referring to himself as the messianic Maitreya Buddha and requiring his subjects to worship him. He began to slaughter Silla captives as well as those who disagreed with this religious sentiments, even his own wife.

Gung Ye’s rule soon became unpopular, and he was deposed by a group of his own generals, the leader of whom, Wang Gun, founded the Goryeo dynasty. According to the histories, this coup took place after Wang Gun received a mysterious engraved bronze mirror from China, which allegedly displayed a prophecy that he would ascend to the throne. Despite the ignominious end to his personal cult, Gung Ye’s influence was instrumental in establishing Buddhism as the official state religion of the new state.

5 German Christian Movement

There were varied responses in the German Protestant community to the rise of National Socialism, one of which was the 1932 founding of Glaubensbewegung Deutsche Christen, or the German Christian Movement. It sought to combine racial and religious doctrines and committed to the task of Entjudung, or the de-Judification of Christianity. This was to be achieved through the rejection of the Old Testament and the exclusion of Hebrew words like “hallelujah” from Christian worship.

When the Nazis came to power, the German Christian Movement increased in influence, eventually reaching a membership of 600,000. It sought to create a Reich church, in other words, a unified Protestant church in Germany. They promoted the idea that Jesus Christ wasn’t Jewish but rather Aryan and sought to prove that Nazi racial theories had a basis in theology. Churches associated with the German Christian movement were often adorned with swastikas.

This movement was opposed by the Bekennende Kirche, or the Confessing Church Movement, which sought to defend the Old Testament and to reiterate the allegiance of the church to God and scripture rather than the Nazi state. However, this was largely an internal ecclesiastical affair, with the Confessing Church movement trying to keep the influence of the Nazi state out of religious matters rather than opposing the National Socialist agenda per se.

Due to the opposition of Confessing Church and the existence of a large neutral faction that tried to keep out of political matters, the German Christian Movement never achieved the dominance over German Protestantism that it had sought. Despite support for the movement in 1932 and 1933, Nazi authorities later treated the movement with indifference or hostility. Although the German Christians attempted to win favor with the Nazi secular authorities, they were instead treated as a disruptive influence, an ideological distraction, and a bold-faced attempt to exploit and potentially control the National Socialist political movement.

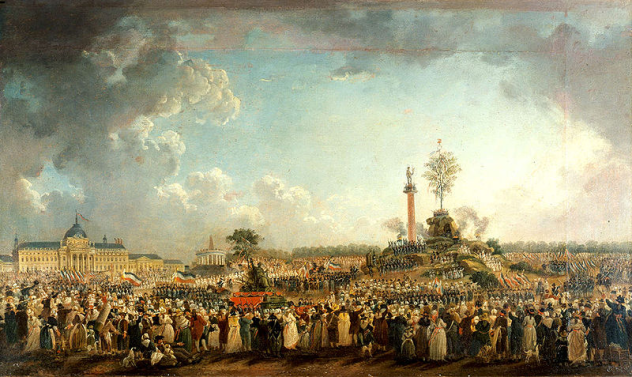

4 Cult Of Reason

Among the radical changes sought during the French Revolution, one of the most shocking was the movement to de-Christianize France (and, eventually, the rest of Western Europe). Although the Constitution of Year 1 had proclaimed freedom of religion, some in the movement held deep anti-clerical sentiments. The Legislative Assembly sought to ban priestly vestments and celibacy and to enforce secular burials emphasizing death as eternal sleep. Anti-clerical forces used the suspension of the Constitution until peacetime to ban Sunday services and commit acts of vandalism and pillage against Catholic churches.

In 1792, constitutional clergy, who served the ideals of the Republic, had difficulties as anti-revolutionary laypeople refused to accept baptism or sacraments from priests who had sworn an oath to the Constitution. The secular authorities took over the role of recording births, baptisms, and deaths. They also legalized divorce, which triggered the flight of the clergy from the revolutionary camp.

This atmosphere led to the establishment of the Cult of Reason, through which “patriotic missionaries” sought to replace the Catholic Church as a national unifying force. But the result was a muddled creed of a civil religion which took over churches and staged rituals and processions. On November 7, a great festival was held for the Cult of Reason in Paris and the provinces, centered around an opera libretto performance in which a young actress played the role of the Goddess of Reason.

The new Cult was characterized by dramatic flare, public spectacle, and internal contradiction, later called “a religion for the eyes and ears” and a “crude caricature of Catholic ceremonies.” Robespierre and other Deist revolutionaries disapproved of both the pagan idolatry in the worship of the Goddess of Reason and the atheism, which Robespierre saw as “aristocratic.” He preferred Deism, and after having radical journalist Jacques Herbert and other leaders of the Cult of Reason sent to the guillotine, he attempted to institute his own new national religion.

3 Cult Of The Supreme Being

After shutting down the Cult of Reason, Maximilien Robespierre gave an address proposing a civic religion to worship the “supreme being.” He believed that society required a moral code, which could only be provided by belief in the immortality of the soul and belief in a higher power.

The religion was launched in June 1794 with the Festival of the Supreme Being, which began with a rousing sermon from Robespierre:

Generous people, do you want to triumph over all your enemies? Practice justice and render to the Supreme Being the only form of worship worthy of him. People, let us surrender ourselves today, under his auspices, to the just ecstasy of pure joy. Tomorrow we shall again combat vices and tyrants; we shall give the world an example of republican virtues: and that shall honor the Supreme Being more.

This address was followed by the ritual burning of a statue representing atheism, after which the assembly made its way to the Champ de Mars, where a symbolic mountain had been erected. Robespierre and his deputies ascended it under the watchful gaze of an enormous statue of Hercules, which represented the people. The Festival was popular, and similar events were held in the provinces.

The new cult featured four great festival days, which commemorated the key dates of the revolution—the fall of the Bastille, the deposing of the monarchy, the execution of Louis XVI, and the fall of the Girondins. Every 10th day, called the decadi, was a day off in commemoration of republican ideals, patriotism, and sacrifices.

However, the Cult didn’t outlive Robespierre by much. He would ultimately fall from power and be executed seven weeks and a day after the Festival of the Supreme Being. Many of the other Jacobins had been suspicious of his intentions. The new faith lacked the spiritual satisfaction of old-regime Catholicism, and for many laypeople, the Cult was inextricably associated with the Terror.

2 Thing Movement

Heinrich Himmler was keen to replace Christianity with a new pseudo-pagan religion that combined ancient German paganism, Sun and Moon worship, ancestor veneration, and nature cults. Based on the Romantic Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil) ideology, 1933’s Thing Movement was to be centered around the ancient Scandinavian “thing,” or people’s assembly. Many National Socialists were dismissive of Christianity and sought to recreate the “glory” of ancient Germanic worship, at least the way it was reported by Roman author Tacitus.

The Thing Movement sought to establish open-air theaters called thingstatten, based on ancient Greek and Roman prototypes. They were to be established at locations of significant archaeological evidence of ancient Germanic occupation. Here, they would showcase thingspiele, pseudo-religious combinations of festivals, military ceremonies, and morality plays.

Establishment of a thingstatte was an honor that was competed for among different German municipalities. The first was built in Halle in 1934, and 12 had been dedicated by September 1935, though there were plans for some 1,200 of them. One was established at the Heiligenberg summit in Heidelberg, despite the fact that there was little evidence of permanent Germanic occupation of the site (though there were two Roman watchtowers there). Fabricated evidence brought it thingstatte status, but there was only time for one thingspiele before the whole movement was scuppered. Meanwhile, construction of the amphitheater ended up destroying what prehistoric remains had been present at the site.

The Heidelberg thingstatte was an outdoor amphitheater with stone seats around a central stage with towers on the flanks, designed to resemble a human torso. Joseph Goebbels attended the first and only thingspiele, in which choirs dressed in robes chanted and sang a narrative of the rise of the Nazi party. Goebbels was not impressed and soon warned against the development of such cults at a party rally in Nuremberg.

Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders never thought very much of the neo-pagan movement, and it was soon quashed in 1935 by the Ministry of Propaganda due to fears of a Christian backlash. After 1936, many of the remaining thingstatten were used as the sites of secular festivals or theaters, with some playing host to open-air rock concerts and film screenings after World War II.

1 God-Building

Despite the state atheism of the USSR, some early Bolshevik thinkers had very different heterodox ideas about the relationship between religion and Marxism. They were the God-building movement, or bogostroitel’stvo. Author Maxim Gorky was a major proponent, and the movement’s main theorist was Anatoly Lunacharsky, who would be the first Soviet commissar of enlightenment (education).

Lunacharsky believed that religion was vital to the actualization of human potential, and that Marxism could be transformed into a humanistic faith. Karl Marx was a Jewish “gift to mankind,” along with Jesus Christ and Spinoza. Lunacharsky believed that religion was the source of human enthusiasm, and Marx’s vision could therefore only be achieved through religious conviction.

Religion provided a warmth absent from a purely materialistic Marxist outlook and an emotional appeal which would rally and elevate the human spirit. In 1907, he wrote, “Scientific Socialism is the most religious of all religions, and the true Social Democrat is the most deeply religious of all human beings.”

Lunacharsky argued that there was much to be learned from early Christianity, which was a revolutionary movement for democracy and equality until it was corrupted by corrupt clergy. He used this claim as a springboard to argue that Marxism could be transformed into a secular and anthropocentric religion, placing man in the place of God and through the revolution allowing humanity to achieve its true potential and paradise on Earth.

Lenin hated God-building, from both a philosophical and a political perspective. In a letter to his friend Gorky, he referred to the whole concept as “ideological necrophilia” and “democratic philistinism.” He considered the whole business a reactionary fancy attraction for mystical-minded bourgeoisie and a distraction from the practical and materialistic cause of the revolution. He repeatedly attacked the God-building movement and its then-leader, A.A. Bogdanov, eventually dispersing it.

Lunacharsky respected Lenin’s disavowal of God-building as a movement but personally continued to evoke its spirit. Indeed, he was instrumental in the later development of the Cult of Lenin and the emergence of ritualized Soviet ceremonies.

David Tormsen actually is the Maitreya Buddha, but he doesn’t want to get into politics. Email him at [email protected].