Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Forgotten Republics From World History

We think of many historic rulers as autocrats, with rule based on heredity and the sword. Before the Age of Enlightenment, the main exceptions were the democratic cities of ancient Greece, the Roman Republic, and the Italian maritime republics.

Thus, the idea of popular representation of the citizenry is often seen as a quintessentially Western cultural product that is nonexistent elsewhere. This belief may be incorrect because sources of proto-democratic thought and behavior can be found in unusual places throughout history.

10 Lanfang Republic

In the 18th century, the West Kalimantan region of Borneo was divided into three sultanates that were interested in exploiting the local deposits of gold, tin, and other valuable minerals.

The coastal areas were inhabited by Javanese and Bugis immigrants while the native Dayak people inhabited the interior. At Singkawang, Sultan Panembahan brought in 20 Chinese workers from Brunei after hearing of their industrious work ethic.

In response, Sultan Omar, his rival, offered leases to the Chinese to settle the area. By 1770, lease deals offered by the sultans had increased the population of Hakka Chinese on the island to 20,000. They formed cooperative business ventures known as kongsi for mutual protection and support.

One kongsi leader named Low Fan Pak (aka Low Lanfang) was an ambitious man who went abroad to seek his fortune after failing China’s civil service examinations. His leadership of a kongsi that oversaw mining operations near the township of Kuntian brought prosperity to the region but fanned the flames of rivalry between the sultanates.

Drawn into local struggles, Low’s kongsi became so powerful that two of the sultanates signed treaties with him. One even entered into his protection, as did most of the other Chinese kongsi.

Low now controlled significant land and population. But rather than declaring himself a sultan, Low reorganized the kongsi as a republic with a constitution and elections. Apparently, he had learned of democratic rule from reading European texts.

Some claim that he would have been committing an act of treason as a Chinese subject by declaring his own sultanate. This would have also put his family back home at risk. Others claim that the Qing emperor declined his petition to set up such a distant client kingdom.

Low was elected as the first president of the republic in 1777 and ruled until his death 18 years later. The Lanfang Republic featured local democratic governance, a judiciary and legislature, and departments of education, finance, and defense. However, there was no standing army.

The republic survived for 107 years before it was conquered by the Dutch in 1884. The story of the republic was preserved by the son-in-law of the last president in a book that was translated into Dutch in 1885. Some believe that there may have been other kongsi republics in the East Indies during this period, but no records remain of their existence.

9 Tlaxcala

The Aztec Triple Alliance was formed by the Aztec cities of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. In the period before the Spanish conquest, they were able to dominate much of Central Mexico with one key exception: the free city of Tlaxcala, which maintained a unique, council-based government. Positions in the government were often awarded based on merit rather than noble lineage.

Tlaxcala was divided into four separate states (known as tlahtocayotl or altepetl): Tepeticpac, Tizatlan, Ocotelulco, and Quiahuiztlan. The basic social units of these states were noble houses called teccalli.

These teccalli were led by lords known as teuctli. They controlled land belonging to both the house as a whole and by individual nobles within the house. Intermarriage was common and helped to establish a civic unity among the houses.

According to the record of Hernan Cortes’s secretary, Francisco Lopez de Gomara: “Tlaxcala, like Venice, is a republic governed by nobles and rich men, and not by one man, which they would regard as tyranny.”

In Spain, Tlaxcala was considered by humanists as “somewhat democratic, somewhat aristocratic, as was the Roman government before it descended into violent monarchy.”

Tlaxcala supported the Spanish invasion of the Aztec Empire. In recognition of their loyalty, much of their aristocracy remained intact under the Spanish Crown. With the subsequent fusion of Nahuatlan and Spanish political structures, many credit the legacy of Tlaxcalan patriotism and sense of civic duty with the rise of republican sentiments in 19th-century Mexico.

8 Commune Of Rome

In the early 12th century, Rome was dominated by the papacy and an aristocracy. In the 1130s, things heated up during a schism between two papal claimants, Innocent II (supported by the Holy Roman Emperor Lothar II) and Anacletus II (supported by the Romans and the king of Sicily).

Lothar attempted to forcibly install Innocent in Rome, but his forces were unable to conquer those areas loyal to Anacletus. It took until the death of Anacletus in 1138 for Innocent to properly return to Rome and be generally recognized.

During the struggle, however, the Romans had developed resentment over papal interference with local affairs. In 1142, the city of Tivoli defeated Roman forces in a conflict. The Romans responded by storming the capital and setting up a senate of 56 members.

This established the Commune of Rome. It was led by the powerful Giordano Pierleoni, who took the title of patrician. The supporters of the commune were largely middle-class: minor land and farm owners, merchants, civil servants, and artisans.

In 1144, a revolt within the commune brought down Pierleoni and began to conceive of itself as the rebirth of the ancient Senatus Populusque Romanus. Violent struggles and negotiations with the papacy continued.

From 1146 to 1155, the Roman commune was heavily influenced by Arnold of Brescia, a radical preacher. He called the College of Cardinals “a house of trade and a den of thieves” and the Pope “a man of blood.”

A compromise was reached in 1145. The Pope accepted the senate, but the senators were under papal authority. This agreement wouldn’t hold, and there were cycles of violence and renegotiation. During this period, the senate held judicial and executive functions, controlled foreign policy, and dated official documents from the reestablishment of the senate.

In 1188, Clement III came to an agreement with the senate that allowed the Pope to return to Rome and had the senate pledge fealty to the papacy. In return, the Pope was obliged to give gifts to individual senators and pay 45 kilograms (100 lb) of silver each year to help maintain civil wars. He also refrained from standing in the way of Roman territorial conflicts with other Italian cities.

7 Republic Of Bou Regreg

The Bou Regreg region was an important port area from the 11th century onward. It served as a cultural bridge between urbanized Cordoba in Spain and the rural Berber population in North Africa.

The most important cities were Casbah, Old Sale, and New Sale. They grew in power as other Moroccan ports were occupied or crushed by Spain and Portugal from the 15th century onward.

In the early 17th century, Moors forced out of Spain by Philip II flooded into the area. These included the Hornacheros (Berber descendants who settled in Casbah) and the more Hispanicized Andalusians (who settled in New Sale).

Andalusian wealth had funded the development of flotillas of corsairs, which prowled the Mediterranean and Atlantic. Meanwhile, the Hornacheros were resistant to the imposition of governors by the sultan of Morocco.

In 1627, Casbah and New Sale united as the Republic of Bou Regreg, which was ruled from Casbah by an elected chief and a council of 16 advisers. The Andalusians of New Sale revolted against Casbah political domination in 1630 with the help of al-Ayachi, a powerful marabout leader who operated out of Old Sale. This increased the political influence of the Andalusians but solved none of the internal struggles conclusively.

Political struggles between Old Sale, New Sale, and Casbah continued over the years, even as the Bou Regreg corsairs became feared pirates and slavers ranging as far as the Thames, Iceland, Newfoundland, and Acadia.

Violent struggles for relative influence between the three cities weakened the republic over time. In 1664, the republican pirate cities finally came to an agreement to equitably distribute the proceeds of piracy.

Two years later, however, their pretensions of independence were wiped out when they were brought under the central authority of the powerful Alawite sultan. The freedom-loving corsairs became piratical organs of the Moroccan government.

6 Zaporozhian Sich

Zaporozhia was a Cossack state that arose in southern Ukraine when the Ukrainian homesteaders fled to the frontier to escape oppressive Polish-Lithuanian rule. From the mid-16th century to 1775, this region was home to a sociopolitical order under which all Zaporozhian Cossacks were considered politically equal. It was centered on a fortress known as the Zaporozhian Sich, which changed locations several times over the centuries.

The central governing authority was the Sich Council. The council held executive, judicial, and administrative roles in matters of war, diplomatic relations, and the distribution of produce from collective farms and fishing districts. In theory, any Cossack could participate at Sich Council assemblies. In practice, however, poor Cossacks and landless peasants were excluded from the proceedings.

The sich elected a chief executive officer called the Kish ataman. His decisions were absolute during wartime, although they could be appealed to the Sich Council during peacetime. The Kish ataman only served for one year. He could neither be impeached nor reelected.

Although there were dreams of formal statehood, the Zaporozhian Sich was an informal affair that made up for a lack of written laws and a division between government and military with a hearty atmosphere of heavy drinking and derring-do. One Venetian envoy remarked, “This republic could be compared to the Spartan, if the Cossacks respected sobriety as highly as did the Spartan.”

Catherine the Great, empress of Russia, eventually wiped out Zaporozhian independence by removing most of the Cossack fighting men to another theater of war, flooding the area with Russian troops, and burning the sich to the ground.

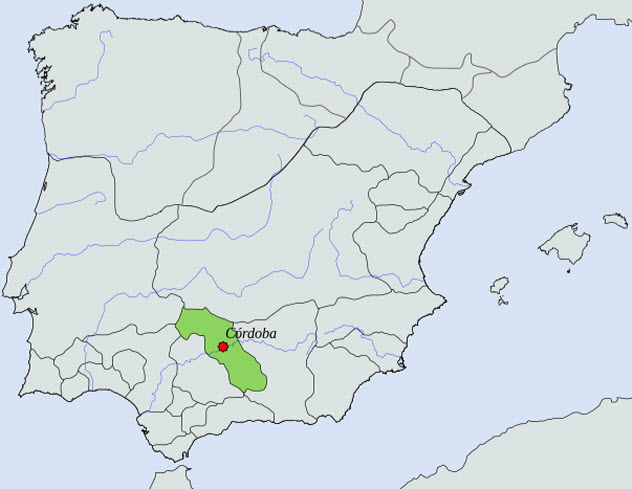

5 Taifa Of Cordoba

The Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba was the most powerful kingdom of Al-Andalus (aka Muslim Spain) at the beginning of the second millennium. But after the death of powerful royal adviser al-Mansur ibn Abi’Amir in 1002, the caliphs lost their ability to exert their authority. The caliphate collapsed into petty states known as taifas, where military leaders ruled over private fiefdoms that bickered among themselves.

The caliph continued to rule in the capital of Cordoba until he was deposed by its citizens in 1031. With the consent of a popular assembly, an oligarchical republic was set up and ruled by the influential Banu Djawar family.

The Banu Djawar had been important members of the Umayyad court since the 800s. But after Umayyad ruler Hisham III was deposed, the new authorities elected Muhammad ibn Djahwar to leadership. Choosing to rule in a triumvirate, he refused to take the title of caliph or king. He was highly praised for this and for his policies that regulated taxes, improved the economy, and restored order through a civilian militia.

Later, the Taifa of Seville claimed that the deceased Caliph Hisham II had reappeared. Initially, the Cordobans didn’t refute this claim in the interest of weakening another pretender to the throne. When Seville suggested that the false caliph be reinstalled in the palace at Cordoba, an embassy was sent out to declare the whole thing a ruse. This led to a brief military conflict with Seville.

Power in the oligarchic republic was passed down to ibn Djahwar’s son and then his grandson. But this situation was not to last. In 1069, Seville seized Cordoba. Then Cordoba was conquered by Castile-supported Toledo in 1075 and by Seville again the following year.

4 Commonwealth Of Iceland

In 870, the first Norse settlers of Iceland came from Scandinavia for economic opportunities and possibly to escape the tyranny of unifying monarchical forces. In 930, the Icelandic chieftains formed an assembly called the Althingi, a legislative and judicial system based on Norwegian traditions. For two weeks every summer, it met at assembly plains called Thingvellir to change laws and hold courts.

However, there was no centralized executive. Power was distributed among the gothar (“chieftains”), who held some legislative power but no formal executive power. For much of early Icelandic history, the power of the gothar was based on personal relationships with the farmers whom they protected and the thingmen who supported them.

For the first few centuries, Iceland had a broad distribution of power and wealth that was unseen elsewhere. However, it was difficult to enforce Althingi judicial decisions, which led to a significant degree of feuding.

Things began to change in the 12th century as some gothar increased in power and began to exert executive power over specified territories. Local assemblies gave way to centralized decision-making. The concentration of power led to jockeying for influence among powerful chieftaincies, which led to open warfare in 1235.

This period of violence was dubbed the Age of the Sturlungar after the most powerful family of the time. In the competition for hegemony, many chieftains killed each other. Finally, Iceland agreed to accept the rule of Norwegian King Hakon in exchange for peace.

3 Phoenician Republics

The Phoenician people flirted with popular representation frequently, although their governments are usually classified as monarchies. However, their kings were usually restricted to authority over the religious realm. Political power was held by administrative institutions with shades of oligarchy and democracy. Without any decision-making power in the secular realm, Phoenician kings usually acted more like high priests.

Egyptian records of diplomatic correspondence between the pharaoh and Phoenician puppet states indicate that some kings greatly feared popular unrest. For example, the king of Byblos complained of being attacked by a man with a bronze knife.

In other cases, communities were ruled for long periods by elder councils when there was no appointed ruler. Later records indicate that councils constrained the power of the king, which likely reflected the power of the wealthy merchant class in Phoenician cities.

After a siege by the Neo-Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II, the city of Tyre adopted a republican system for a short period. It was ruled by elective magistrates called suffetes. It only lasted seven years in Tyre, but an even more democratic system was exported to the colony of Carthage. There, two suffetes were elected every year and shared power with the aristocratic senate. When the suffetes and the senate disagreed, a popular assembly was called to decide the issue.

The philosopher Aristotle praised the Carthaginian constitution, comparing it to the Spartan and Cretan systems. He saw Carthage as a mixture of aristocracy, oligarchy, and democracy, although it must be remembered that he was using the Greek definitions of those concepts.

For our purposes, it is clear that republican and partially republican structures were common in the Phoenician world. Monarchy and despotism was rare compared to other cultures. Some even suggest that the republican strand running through Phoenician society may have been an influence on the rise of democracy in Athens and other Greek cities.

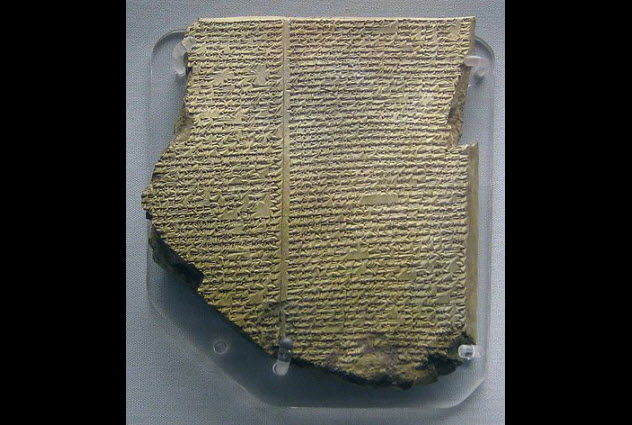

2 Mesopotamian ‘Primitive Democracy’

In old historical writings, Mesopotamia is often seen as a model for “Oriental despotism” when compared to the democratic tradition originating from Greece. However, some academics have different views regarding the levels of popular political participation in the lands of the Tigris and Euphrates.

In the 1940s, the academic Thorkild Jacobsen used Sumerian myth, epic poems, and historical records to argue for the existence of “primitive democracy” in Mesopotamia before the rise of Babylon. The power in this period was believed to be held by free male citizens.

However, Jacobsen said that “the various functions of government are as yet little specialized, the power structure is loose, and the machinery for social coordination by means of power is as yet imperfectly developed.”

He claimed that the power of kings in early Sumer was limited by councils of elders and councils of young men who held the ultimate political authority. They needed to be consulted about war and the choice of rulers. In more despotic states like Babylon and Assyria, these political structures devolved into judicial assemblies.

Many academics saw Jacobsen’s theories as cherry-picking and misinterpretation. But some have backed him up. Adolf Leo Oppenheim described Mesopotamian society as the fusion of a power structure around an often divine king.

Oppenheim described it as “the community of persons of equal status bound together by a consciousness of belonging, realized by directing their communal affairs by means of an assembly, in which, under a presiding officer, some measure of consensus was reached.”

According to Raul S. Manglapus, the mythology of Sumer and Akkad projected contemporary democratic traditions into the divine realm in which there was an assembly of deities called the Ubshuukkinna. Using records from the city of Elba from 2500 BC, Manglapus noted that the king was elected for a period of seven years and shared power with a group of elders.

Kings who lost reelection retired with a state pension. Manglapus also suggested that Babylonian legends of goddesses attending divine assemblies may have reflected a political society where women could participate. If true, this would make Mesopotamian systems even more democratic than their Greek counterparts.

1 Ancient Indian Republics

There is significant evidence that republics resembling Greek city-states and Roman republics were present in India during the time of the Buddha. Polities of the time were referred to as gana or sangha (“multitudes”). While some of these polities possessed kings, others were oligarchical republics in which members of the Kshatriya warrior classes participated in political assemblies.

The Rig Veda includes evidence of this: “We pray for a spirit of unity; may we discuss and resolve all issues amicably . . . may we distribute all resources (of the state) to all stakeholders equitably, may we accept our share with humility.”

Generally, conservative Brahmanic literature preferred to paint monarchy as the ideal form of government. The Buddhist Pali Canon contains references to complex voting procedures and constitutional constraints that were used in early monastic communities.

Meanwhile, in the Mahaparinibbana Sutta, one of the oldest Buddhist texts, the Buddha refers to a polity called the Vajjian confederacy holding frequent public assemblies. He tells a would-be conqueror that this is the source of the state’s prosperity.

Greek sources also give credence to Indian republicanism. Arrian’s Anabasis of Alexander describes the Macedonian conqueror encountering free and independent polities with few references to kings. Descriptions of the northern Indian republics indicate that many were much larger and more populous than the republican Greek city-states of the same period.

It is probably impossible to know how many republics actually existed in ancient India. States identified as republican include Sakyas of Kapilvastu (the birthplace of the Buddha), Koliya of Rama Game, Mallas of Kushinagar, and Lichchvis of Vaisali.

The republics were gradually overshadowed by kingdoms called mahajanapadas, one of which became the powerful Maghdan Empire. The disappearance of republican systems likely had multiple causes.

With voting linked to tribal identities, republics probably didn’t perform well on larger scales and were vulnerable to powerful and united neighboring kingdoms. Such neighbors could often stir up discord within republican states, weakening them from the inside through infighting.

If David Tormsen was in charge of a kongsi republic, he’d call himself a patrician. Email him at [email protected].