Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

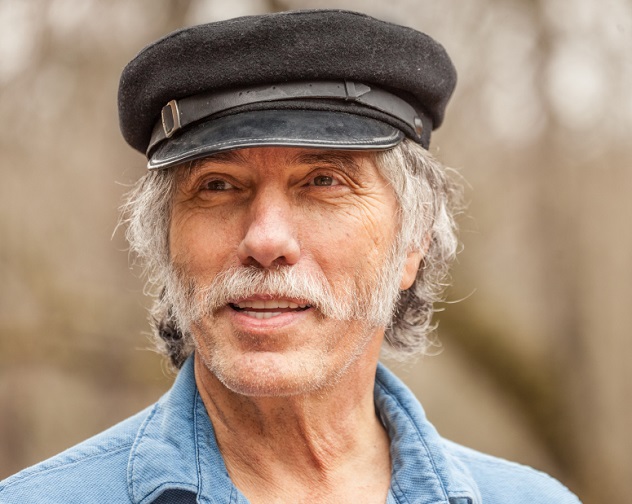

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Fascinating Historical Origins Of Everyday Idioms

Some words and phrases we use today still hold their original meanings. Others have evolved into something completely different, their origins disguised by the passage of time. Rediscovering the origins of old words sheds light on their modern meanings.

10 Scapegoat

Today’s meaning: A person who is blamed for the mistakes of others

Today’s meaning: A person who is blamed for the mistakes of others

Real goats may be saddened to learn the origins of “scapegoat,” which was birthed in an ancient Hebrew tradition. Yom Kippur was a day of atonement and the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. Made from the Hebrew words for “goat for Azazel,” “scapegoat” was first used in 1530 by William Tyndale. In Tyndale’s English translation of the Bible, the word “Azazel” only appears in the context of one particular Jewish ritual. Cutting it into two words, Tyndale translated it as “the goat which escapes” or “escape goat.”

Heeding the ritual was a way for the Israelites to be absolved of their sins, and it started with two goats being presented to the high priest. After the presentation, one was given as a sacrifice to Jehovah and the other was saved for a special purpose. Every one of the sins of the people were placed on the head of Azazel’s goat before it was led out into the wilderness. Like an unwanted child in a Brothers Grimm tale, the goat was simply abandoned away from civilization—according to some historians. It was much more likely that the goat was led to the edge of a cliff and “encouraged” to jump off. (The Hebrew word Tyndale translated as “escape” is more commonly translated as “go away forever.”)

9 White Elephant

Today’s meaning: Something that costs more than it’s worth

Today’s meaning: Something that costs more than it’s worth

Coming from the kingdom of Siam (modern-day Thailand), this phrase was birthed from the customs of the Siamese kings. When the king took offense at something someone said or did, he didn’t leap straight to an execution. Offended but fair, he would grant the victim a gift, a symbol for the country itself: a white elephant. The offender was unable to refuse the gift, as doing so was equivalent to treason. Why would someone refuse such a lavish gift? Because taking care of the elephant would likely make the offender go bankrupt.

The introduction of the phrase into the English lexicon was hurried by the famous showman and circus owner P.T. Barnum. One of the first to bring one of the venerated animals out of the country, he introduced it to a rapt public desperate for the exotic. None of the spectators were happy when they discovered the elephant presented to them was light gray instead of white. Barnum himself knew they weren’t supposed to be milky white and worked to dispel the myth that they were.

8 Running Amok

Today’s meaning: A sudden assault against people or objects; out of control

Today’s meaning: A sudden assault against people or objects; out of control

Seen today as a genuine psychiatric condition found in nearly every culture on the planet, the phrase, as well as the idea itself, comes from the tribesmen of the Malay people in the 1700s. Excused as a curse laid down on someone by malevolent spirits, a person who was running amok would often be unable to reason, harming everything within reach until subdued. Sadly, the sufferer was often killed in the process.

In the 1770s, one of the earliest Western depictions of the ailment was given to us by the British explorer James Cook, who wrote about an episode he witnessed firsthand. The psychosis often resulted in the maiming of multiple victims and occurred without warning, cause, or target. The word itself derives from the Malay word mengamok, which roughly translates as “to make a furious and desperate charge.”

7 Gadzooks

Today’s meaning: An exclamation of surprise or annoyance

Today’s meaning: An exclamation of surprise or annoyance

“Gadzooks” is an expression known as a minced oath, meant to allow Christians to avoid taking the Lord’s name in vain. The English Parliament actually passed a bill in the early 1600s to make it a fineable offense to “profanely speak the holy name of God.” It didn’t take long for Christians of the time to find ways around the fine. Eventually, “God” was changed to “gad” or “od” when combined with other words to make this easier.

The word “gadzooks” was the euphemistic form of the phrase “God’s hooks,” itself a reference to the nails or spikes that held Christ to the cross. Yet another phrase is “odds bodkins,” similar to “gadzooks,” with it taking the place of “God’s body.”

6 Add Insult To Injury

Today’s meaning: To make a bad situation worse

Today’s meaning: To make a bad situation worse

Ultimately derived from Aesop’s fable “The Bald Man and the Fly,” this phrase finds its origins within the translation of the Roman writer Phaedrus, who lived in the first century AD. In the story, a fly bites a bald man on the head. When the man tries to swat the fly, he strikes himself in the head and wounds himself mortally. As the man lies dying, the fly flits in circles above him and taunts him, condemning him for making himself look bad and for killing himself. In other versions of the story, the man lives but still suffers the indignity of having the fly mock him. (The original fable, perhaps the strangest surviving version, has the man hit the fly and then insult himself.)

Unfortunately for Phaedrus, the Roman emperor Sejanus objected to his writings, claiming they painted him in a derogatory light. Neither the exact punishment, nor Phaedrus’ fate, has ever been discovered, but one theory is that he was exiled and continued to write while suffering his punishment.

5 Between A Rock And A Hard Place

Today’s meaning: Having to choose between two undesired options

Today’s meaning: Having to choose between two undesired options

A phrase similar in meaning to “between a rock and a hard place” has existed since the fourth century BC. The exact phrase is much newer, only dating to the 20th-century US. Coined by miners, it then referred to choosing between unemployment and strenuous, low-paying work at the mine. Those miners probably didn’t know the phrase originally came from the Greek poet Homer.

In the epic poem The Odyssey, Odysseus and his men have to travel through the Straits of Messina, an area of the sea guarded by two fearsome monsters: Scylla, a monster with six mouths and 12 feet, and Charybdis, either a sea monster who produced a whirlpool or simply a whirlpool itself. Opting for either one was sure to result in death, for at least some of the crew, so the phrase “between Scylla and Charybdis” came to mean having to choose the lesser of two evils.

4 Bust One’s Chops

Today’s meaning: Call one’s bluff; criticize someone

Today’s meaning: Call one’s bluff; criticize someone

In the 1800s, when sideburns (and Ambrose Burnside) were at the height of their popularity, this phrase was often used as a challenge to someone’s integrity. The phrase fell out of popular usage around the start of World War I, as men needed to shave the sides of their faces in order to accommodate protective gas masks.

As a phrase, it was not only to be taken figuratively, “bust one’s chop” was also to be taken literally. A “bust to one’s chops” could reference a punch to the side of one’s face. Thanks to the popularity of sideburns between the 1950s and the 1970s, and men like Lemmy, the phrase made a brief comeback before fading into relative obscurity today.

3 Give The Cold Shoulder

Today’s meaning: To disregard someone

Today’s meaning: To disregard someone

Although its true origins are unclear, the earliest written evidence of this phrase comes from the writings of Walter Scott, a Scottish poet and novelist who lived in the 18th and 19th centuries. Though his work never mentions food or gives any indication as to its origin, it is believed that it derives from an earlier phrase “to give the cold shoulder of mutton.”

The older phrase was used with an unwanted guest in another’s house. To save face or to avoid an awkward conversation, the host might serve an inferior cut of meat (cold mutton, for example) to indicate to that particular person they were not welcome any longer.

2 Basket Case

Today’s meaning: A person or thing unable to handle their situation; a crazy person

Today’s meaning: A person or thing unable to handle their situation; a crazy person

Used in the US as far back as 1919, the phrase finds its origins in war. Most of the earliest uses refer to a person who had all four of their limbs amputated, indicating they were “stuck in a basket,” with some feeling this was literal. Despite the repeated denial by military officials of the existence of any soldiers who were actually stuck in baskets, the rumor persisted for a number of decades.

The modern meaning came to us years later, possibly as early as the late 1940s. But the modern meaning is just a natural evolution of the phrase. As someone with their limbs amputated would be unlikely to be able care for themselves, it would stand to reason neither would a person with severe mental difficulties.

1 In Stitches

Today’s meaning: Laughing uncontrollably

Today’s meaning: Laughing uncontrollably

The Immortal Bard, Shakespeare, coined many phrases, but we’ve picked just one. Derived from a phrase from his time and first used in the play Twelfth Night, “to be in stitches” means to be in such pain from laughter that you feel like you’re being poked by a needle. Even with Shakespeare’s help, the phrase faded from use.

Surfacing again in the 1900s, it had transformed from its original phrasing, “laugh yourself into stitches.” Though not as common today as it was in the 20th century, “in stitches” or “had me in stitches” is now common parlance. Shakespeare’s credits also include “break the ice,” “brave new world,” and “bated breath.” These are just a few of the more than 1,700 words and phrases we can thank the Bard for introducing.